Citizen Trust, Administrative Capacity and Administrative Burden in Pakistan’S Immunization Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water Supply & Sanitation

WATER SUPPLY & SANITATION 149 WATER SUPPLY & SANITATION VISION To improve quality of life of the people of Punjab through provision of safe drinking water and sanitation coverage to the entire community. POLICY This important social sector assumes the policy of provision of safe and potable drinking water, sanitation and coverage of the entire community particularly in barani and brackish areas. Emphasis has been laid on encouraging Participatory Management - Community mobilization in project. Coverage will be provided to the rural areas through encouragement of integrated rural water supply and sanitation schemes. Waste water treatment plants will be provided for improving environmental pollution and protecting Water Bodies. STRATEGIC INITIATIVES / NEW INTERVENTIONS ¾ 993 water supply and sanitation schemes have been conceived for the year 2008-09 with a total financial outlay of Rs.8000 million. Execution of these interventions will result into substantial improvement in the population coverage. ¾ A special package has been reflected in the MTDF 2008-09 under “Community based Sanitation Program”. By implementation of this project there will be visible improvement in the sanitation, particularly in Rural Areas and Small Towns. ¾ MTDF 2008-09 provides “Block Allocation” for various components of the Sector. The schemes against these blocks will be identified through participation of the local communities. ¾ In order to ensure equitable distribution of supplies and for water conservation, water metering concept is being introduced in the rural areas. This intervention will control wastage of water and will lead to the sustainability of the schemes. ¾ Presently there is a huge disparity amongst districts regarding the resource provisions. This imbalance is being minimized by providing more funds to the deprived/low profile districts as defined in MICS. -

Increasing Health Risks by Heavy Metals Through Use of Vegetables and Crops Adnan Hussain

EXTENDED ABSTRACTS Journal of Agriculture Increasing health risks by heavy metals through use of Vegetables and Crops Adnan Hussain University of the Punjab Lahore, Pakistan Abstract metals which, even at low levels, pose serious harm to human health. Wastewater is a very common method of irrigation, primarily because Heavy metal is a problem word described in various ways by a variety of the limited freshwater supplies in developing countries. Through of authoritative bodies. The word is also applied to metals that are wastewater, poisonous metals pose significant hazards for soil, plants poisonous. The concept was first used by Bjerrum in 1936. Heavy and vegetables and also human health. The study aims at assessing metals are now increasingly a global concern. It directly or indirectly the level of metal pollution in untreated wastewater-irrigated soil and influenced the agricultural system. We face very severe health issues vegetables. One of the key forms in which these elements enter the because of this. Pakistan faces this question, too, since many countries human body is by ingesting foods that contain heavy metals. Heavy throughout the world lack clean water. Swage and industrial water metals are placed centrally in fatty bone tissues, which cover noble are rich in nutrients. It is because farmers use this toxic wastewater in minerals. Heavy metals can cause a variety of diseases gradually being order to produce greater yields for irrigation purposes. Farmers use released into the body. these types of water in urban areas in Pakistan to increase irrigation The consumption by crops and vegetables of heavy metals is health risks. -

Bulleh Shah Packaging

January 15, 2020 Ref No.: BSP/SUS/2020/001 SCHEDULE 1 (REGULATION 3(1) FORM OF APPLICATION The Registrar, National Electric Power Regulatory Authority Subject: APPLICATION FOR A GENERATION LICENSE I, Syed Aslam Mehdi, CEO of Bulleh Shah Packaging {Private} Limited, hereby apply to the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority for the grant of a Generation License to the Bulleh Shah Packaging (Private) Limited' pursuant to section 14B of the Regulation of Generation, Transmission and Distribution of Electric Power Act 1997. I, certify that the documents-in-support attached with this application are prepared and submitted in conformity with the provisions of the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority Licensing (Application and Modification Procedure) Regulations, 19992, and undertake to abide 7 by the terms and provisions of the above-said regulations further undertake and confirm that the information provided in the attached documents-in-support is true and correct to the best of my knowledge and belief. A Pay Order No. 107043981 dated 10-01-2020 amounting PKR-366,000/- (Rupee Three Hundred sixty six thousand Only) being the non-refundable license application fee calculated in accordance with Schedule II to the National Electric Power Regulation Authority Licensing (Application and Modification Procedure) Regulations, 1999, is also attached herewith. 4't Sincerely, 7/ 0 ta,\) e-c Syed Aslam Mehdi r• CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER Bullehshah Packaging (Pvt.) Ltd, In ) This is an existing generation facility presently used for self-consumption. Now, the company plans supplying surplus electric power to the tune of 2 MW to a Bulk Power Consumer (BPC) in the name of OmyaPak Private Limited. -

Quarterly Activity Report April-June, 2014

Quarterly Activity Report April-June, 2014 Human and Institutional Development Section (HID) DAMEN 26-C Nawab Town Raiwind Road, Lahore. Phone: 042-35310571-2, Fax: 042-35310473, URL: www.damen-pk.org, E-mail: [email protected] Quarterly Activity Report April-June 2014 Report Written By Aisha Almass – Research & Documentation Officer Report Edited By Rukhshanda Riaz – Manager HID Development Action for Mobilization and Emancipation (DAMEN) PAGE 1 OF 20 Quarterly Activity Report April-June 2014 Table of Contents Quarter Review ........................................................................................................................................................... 3 Social Sector Program ................................................................................................................................................. 4 Quarter Highlights .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Home School Education Program ....................................................................................................................... 4 Health Care services............................................................................................................................................. 6 Health Camp Campaign ....................................................................................................................................... 7 Environmental Consciousness............................................................................................................................ -

24Th June, 2018 No. NA-138/GE 2018 In

ELECTION COMMISSION OF PAKISTAN NOTIFICATION 24th June, 2018 No. NA-138/GE 2018 In pursuance of the provisions of Sub-Section 6 of Section 59 of the Elections Act, 2017 (XXXIII of 2017) read with Sub-Rule 4 of Rule 50 of the Election Rules, 2017, undersigned hereby publishes, for general information of the public, the final list of Polling Stations in respect of National Assembly Constituency No. NA-138 Kasur-II for conduct of General Elections, 2018. By order of the Election Commission of Pakistan &((e5 JU DISTRICT RETURNING OFFICER KASUR ABSRACT OF FINAL LIST OF POLLING SCHEME STATIONS OF CONSTITUENCY NA 138 KASUR-II NO & NAME OF NO.POLLING STATIONS NO.OF VOTES NO.OF POLLING BOOTHS SR CONSTITUENCY MALE FEMALE COMBINED TOTAL MALE FEMALE TOTAL MALE FEMALE TOTAL 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 7 8 9 NA-138 111 95 132 338 246580 181025 427605 544 414 958 KASUR-II A.PPR()VE.9 RAFAQAT ALI QAMAR Returning Officer, saijac-i Officer, NA-138 Kasur-II Ka Rafarit (7arnar Return. h1A FORM 28 [see rule 50] LIST OF POLLING STATIONS FOR A CONSTITUENCY NA-138- KASUR-II Sr. Sr. No & Name of the In case of Rural Areas In case of Urban Areas Sr. No. of voters No. of Voters No. Polling Station on the Electoral Assigned to Polling No. of Polling Booths Rolls in case of bifurcation of Male Female Name of Electoral area Census Block Name of Electoral area Census Electoral Area Male Female Total code Block code 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 1 Govt. -

Lahore Electric Supply Company Limited

LAHORE ELECTRIC SUPPLY COMPANY LIMITED OOFICE OF THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER LESCO HEAD OFFICE22-A QUEENS ROAD LAHORE Phone # 99204801 Fax # 99204803 E-MAIL : [email protected] No.3957/FD/LESCO/CPC/Tariff 2013-14 Dated Jul 04, 2013 The Registrar NEPRA 2" Floor OPD Building, G-5/2 Islamabad. Subject: PETITION FOR DETERMINATION OF CONSUMER END TARIFF FOR FY 2013-14 Enclosed please find the Petition for Determination of Revenue Requirement and Consumer End Tariff for FY 2013-14. The Authority is requested in order to recover the revenue requirement in time the proposed tariff be allowed so that the same may be applicable from Jul 01, 2013 subject to an order for refund for the protection of consumers during the pendency of this petition in terms of Sub-Rule 7 of Rule 4 of NEPRA (Tariff Standards and Procedures) Rules, 1998. Regards, Muhamm d Saleem Chief Ex utive Officer LESCO Enclosed Please find: 1. Tariff Petition for FY 2013-14. 2. Standardized Tariff Petition Formats. 3. Demand Draft of Rs:- 7,760 Bearing No. fated PAKISTAN AFFIDAVIT I, Muhammad Saleem, Chief Executive Lahore Electric Supply Company Limited, (Distribution License # 03/DL/2002 dated April 01,2002) being duly authorized representative/attomey of Lahore Electric Supply Company Limited, hereby solemnly affirm and declare that the contents of the accompanying petition/application # 3957/FD/LESCO/CPC/Tariff 2013-14 dated July 04, 2013, including all supporting documents are true and correct to the best of my knowledge and belief and that nothing has been concealed. I also affirm that all further documentation and information to be provided by me in connection with the accompanying petition shall be true to the best of my knowledge and belief. -

X-Ray Facilities with License Valid Upto 30-06-2020 Sr. No. Name Of

X-ray Facilities with License Valid upto 30-06-2020 Sr. No. Name of Facility Address of Facility District Kasur Pakistan Red Crescent Medical Dina Nath, 48 Km Multan Road, Kasur 1497. and Dental College / Teaching Hospital Noor Hospital Kot Radha Kishen, Kasur 1498. Amin Hayat 1499. Memorial Medical Kot Rukan Din Khan, Kasur Center P.C.M.I Trust Clarkabad Khurd, Kasur 1500. Hospital Social Security Health 8-km Manga Raiwind Road, Kot Radha Kishan, Kasur 1501. Management Company Hospital Bhatti International Raiwind Road, Kasur 1502. Teaching Hospital Khanzada Poly Clinic Main Road, Phool Nagar, Patuki, Kasur 1503. Wali Hospital Liaqat Road, Kasur 1504. Family Medical Liaqat Raod, Near Khan Mehal Cinema, Kasur 1505. Centre Hussain Memorial Circular Raod, Near Telephone Exchange, Kasur 1506. Centre Nawaz Memorial Tariq Colony, Kasur 1507. Hospital Sharif Medical Steel bagh, Liaqat Road, Kasur 1508. Complex X-ray Facilities with License Valid upto 30-06-2020 Sr. No. Name of Facility Address of Facility Al-Shafia Lab and Steel Bagh, Kasur 1509. Diagnostic Center Al-shifa Hospital Phool Nagar, Pattoki, Kasur 1510. Sufi Amant Ali Gulshan-e-Subhan, Patoki, Kasur 1511. Surgical Hospital Nasim Anwar Multan Raod, Pattoki 1512. Surgical Hospital Rafee Clinic New Ghala Mandi Road, Pattoki, Kasur 1513. Rural Health Center Mustafabad, Kasur 1514. (RHC) Tehsil Headquarter 1515. Hospital (THQ Tehsil Pattoki, Kasur Hospital) Rural Health Center Khudian, Kasur 1516. (RHC) Al-Rehman Lab X- Al-Sharif Plaza, Shop No. 17, Steel Bagh, Kasur 1517. ray Center Rooshan Medical Near Islam Pharmacy, Circular Road, Khudian Khas, Kasur 1518. Centre Surayya Orthopaedic and Near Jamia Masjid Awaisia Multan Road, Pattoki, Kasur 1519. -

Population According to Religion, Tables-6, Pakistan

-No. 32A 11 I I ! I , 1 --.. ".._" I l <t I If _:ENSUS OF RAKISTAN, 1951 ( 1 - - I O .PUlA'TION ACC<!>R'DING TO RELIGIO ~ (TA~LE; 6)/ \ 1 \ \ ,I tin N~.2 1 • t ~ ~ I, . : - f I ~ (bFICE OF THE ~ENSU) ' COMMISSIO ~ ER; .1 :VERNMENT OF PAKISTAN, l .. October 1951 - ~........-.~ .1',l 1 RY OF THE INTERIOR, PI'ice Rs. 2 ~f 5. it '7 J . CH I. ~ CE.N TABLE 6.-RELIGION SECTION 6·1.-PAKISTAN Thousand personc:. ,Prorinces and States Total Muslim Caste Sch~duled Christian Others (Note 1) Hindu Caste Hindu ~ --- (l b c d e f g _-'--- --- ---- KISTAN 7,56,36 6,49,59 43,49 54,21 5,41 3,66 ;:histan and States 11,54 11,37 12 ] 4 listricts 6,02 5,94 3 1 4 States 5,52 5,43 9 ,: Bengal 4,19,32 3,22,27 41,87 50,52 1,07 3,59 aeral Capital Area, 11,23 10,78 5 13 21 6 Karachi. ·W. F. P. and Tribal 58,65 58,58 1 2 4 Areas. Districts 32,23 32,17 " 4 Agencies (Tribal Areas) 26,42 26,41 aIIjab and BahawaJpur 2,06,37 2,02,01 3 30 4,03 State. Districts 1,88,15 1,83,93 2 19 4,01 Bahawa1pur State 18,22 18,08 11 2 ';ind and Kbairpur State 49,25 44,58 1,41 3,23 2 1 Districts 46,06 41,49 1,34 3,20 2 Khairpur State 3,19 3,09 7 3 I.-Excluding 207 thousand persons claiming Nationalities other than Pakistani. -

Annual Audited Report 2017

__________________________________________________________________________ 1 Annual Report ____________________________________________________________ C O N T E N T S COMPANY INFORMATION ………………………………….. 3 MISSION ……………………………………………………….. 4 NOTICE OF ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING ………………. 5-6 DIRECTORS’ REPORT ………………………………………. 7-8 FINANCIAL SUMMARY ………………………………………. 9 STATEMENT OF ETHICS AND BUSINESS PRACTICES.. 10 AUDITORS’ REPORT TO THE MEMBERS ………………… 11 BALANCE SHEET ……………………………………………. 12 PROFIT AND LOSS ACCOUNT …………………………….. 13 STATEMENT OF COMPREHENSIVE INCOME ………….. 14 CASH FLOW STATEMENT …………………………………. 15 STATEMENT OF CHANGES IN EQUITY …………………. 16 NOTES TO THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS ……………… 17-31 PATTERN OF SHAREHOLDING …………………………………. 32 FORM OF PROXY ……………………………………………. 2 __________________________________________________________________________ COMPANY INFORMATION CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER : Mr. Muhammad Arshad Saeed BOARD OF DIRECTORS : Ch. Rahman Bakhsh Mrs. Salma Aziz Mr. Muhammad Musharaf Khan Ms. Kiran A. Chaudhry Mr. Kamran Ilyas Mr. Muhammad Ali Chaudhry CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER : Mr. Muhammad Ali Chaudhry COMPANY SECRETARY : Mr. Muhammad Javed AUDITORS : M/s RSM Avais Hyder Liaquat Nauman Chartered Accountants Lahore AUDIT COMMITTEE : Mr. Kamran Ilyas Chairman Mrs. Salma Aziz Member Mr. Muhammad Musharaf Khan Member HR - COMMITTEE : Mr. Kamran Ilyas Chairman Mr. Muhammad Ali Chaudhry Secretary Ms. Kiran A. Chaudhry Member BANKERS : National Bank of Pakistan Bank Alfalah Limited Askari Bank LImited Al Baraka Bank (Pakistan) Ltd. Faysal -

Study of Arsenic in Drinking Water of Distric Kasur Pakistan

World Applied Sciences Journal 24 (5): 634-640, 2013 ISSN 1818-4952 © IDOSI Publications, 2013 DOI: 10.5829/idosi.wasj.2013.24.05.13228 Study of Arsenic in Drinking Water of Distric Kasur Pakistan 1Sheikh Asrar Ahmad, 12Asad Gulzar, Habib Ur Rehman, 2Zamir Ahmed soomro, 2Munawar hussain, 23Mujeeb ur Rehman and Muhammad Abdul Qadir 1Division of Science and Technology, University of Education, Township Campus, 54590, Lahore, Pakistan 2Pakistan Council of Research in Water Resources, Lahore, 54590, Pakistan 3Institute of Chemistry, University of the Punjab, Lahore, 54590, Pakistan Submitted: Jul 17, 2013; Accepted: Aug 26, 2013; Published: Aug 29, 2013 Abstract: The present work deals with the study of arsenic in drinking water of water supply schemes of district Kasur. About 33% of tanneries are working in this district. Tanning is a complex chemical process involving different hazardous chemicals. They discharge toxic metals including arsenic and chromium without treatment. As a result underground water reservoirs get contamination. Arsenic contaminated water may lead to serious health hazards (neurological effects, hypertension, peripheral vascular diseases, cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, diabetes mellitus and skin cancer) when using for drinking. The quality of drinking water is major concern with human health. The study was focused on water supply schemes which are installed at different locations in kasur. The samples were collected from water supply schemes which are providing water for domestic use. Standard method, Atomic Absorption Spectrometer (Vario, 6 Analytic Jena) was used for the analysis of samples. The evaluation of arsenic was conducted for drinking purpose. According to WHO guide line value the analytical data revealed that 50% water samples were found contaminated due to higher concentration of arsenic. -

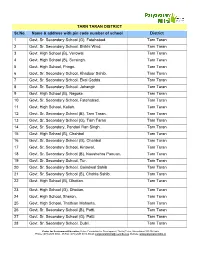

TARN TARAN DISTRICT Sr.No. Name & Address With

TARN TARAN DISTRICT Sr.No. Name & address with pin code number of school District 1 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Fatehabad. Tarn Taran 2 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Bhikhi Wind. Tarn Taran 3 Govt. High School (B), Verowal. Tarn Taran 4 Govt. High School (B), Sursingh. Tarn Taran 5 Govt. High School, Pringri. Tarn Taran 6 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Khadoor Sahib. Tarn Taran 7 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Ekal Gadda. Tarn Taran 8 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Jahangir Tarn Taran 9 Govt. High School (B), Nagoke. Tarn Taran 10 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Fatehabad. Tarn Taran 11 Govt. High School, Kallah. Tarn Taran 12 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Tarn Taran. Tarn Taran 13 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Tarn Taran Tarn Taran 14 Govt. Sr. Secondary, Pandori Ran Singh. Tarn Taran 15 Govt. High School (B), Chahbal Tarn Taran 16 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Chahbal Tarn Taran 17 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Kirtowal. Tarn Taran 18 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Naushehra Panuan. Tarn Taran 19 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Tur. Tarn Taran 20 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Goindwal Sahib Tarn Taran 21 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Chohla Sahib. Tarn Taran 22 Govt. High School (B), Dhotian. Tarn Taran 23 Govt. High School (G), Dhotian. Tarn Taran 24 Govt. High School, Sheron. Tarn Taran 25 Govt. High School, Thathian Mahanta. Tarn Taran 26 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Patti. Tarn Taran 27 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Patti. Tarn Taran 28 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Dubli. Tarn Taran Centre for Environment Education, Nehru Foundation for Development, Thaltej Tekra, Ahmedabad 380 054 India Phone: (079) 2685 8002 - 05 Fax: (079) 2685 8010, Email: [email protected], Website: www.paryavaranmitra.in 29 Govt. -

PAKISTAN RED CRESCENT SOCIETY MONSOON 2011 – Update

PAKISTAN RED CRESCENT SOCIETY MONSOON 2011 – Update Update: 15-08-2011 WEATHER FORECAST NEXT 24 HOURS Widespread thundershowers with heavy falls at scattered places & very heavy falls at isolated places is expected over the upper catchments of Rivers Sutlej, Beas & Ravi. Scattered thunder showers are expected over the upper catchments of River Chenab, North &Northeast Punjab. Isolated thundershower is expected over south Punjab, Sindh & Khyber Pakhtunkhwa MONSOON SPELL CONTINUES Flood Forecasting Division Reports: The current spell of monsoon rains would continue for next 1-2 days in the country. As a result, some more rains with isolated heavy falls are expected in lower Sindh (Districts Hyderabad & Mirpur Khas), upper Punjab (Rawalpindi, Gujranwala & Lahore Divisions) and Kashmir during the next 12 - 24 hours. River Sutlej at Ganda Singh Wala is likely to attain Low Flood Level with flood flows ranging between 50,000 to 70,000 cusecs during the period from 0100 hours PST of 16th August, 2011 to 0100 hours PST of 17th August, 2011. Today: Scattered rain/thundershower with isolated heavy falls in Punjab, Sindh and Kashmir. Scattered rain/thundershower also in upper Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Northeast Balochistan. SIGNIFICANT RAINFALL (in mm) Significant rainfall events reported during the past 24 hours include: Mithi=32, Kotnaina=31,Muzaffarabad=23, Lahore(Shahdara=21,Shahi Qilla=08,Upper Mall=07, Misri Shah &City=06 each& Airport=02),Shakargarh & Bahawalnagar=15 (each),Domel G.S.Wala=14(each), Khuzdar& Rawalakot=12(each), Palandri=11,Murree=08, Balakot =07, Gujranwala(Cantt) &Kakul=06(each), Bahawalpur (City=06 &Airport=03), Sibbi=05, Karachi(Airport)=04, Sargodha(Airport=04&City=03), Chhor, Okara & Kalam=03 (each), Sehrkakota, Kurram garhi, Oghi & Faisalabad=02(each),Sialkot (Airport=02&Cantt =Trace), Ura, Chattarkallas, Phulra, Nowshera, Kotli & Lasbela =01(each), Shorkot, Gilgit, Sahiwal, D.G.Khan, Multan, Bannu & Skardu=Trace(each) RIVERS’ STATUS River Ravi at Balloki is in Low Flood Level and rising.