The Quest for the Origins of Stonehenge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cuisine and Consumption at the Late Neolithic Site of Durrington Walls

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UCL Discovery Feeding Stonehenge: cuisine and consumption at the Late Neolithic site of Durrington Walls Oliver E. Craiga, Lisa-Marie Shillitoa,b, Umberto Albarellac, Sarah Viner-Danielsc, Ben Chanc,d, Ros Cleale, Robert Ixerf, Mandy Jayg, Pete Marshallh., Ellen Simmonsc, Elizabeth Wrightc and Mike Parker Pearsonf aBioArCh, Department of Archaeology, University of York, Heslington, York YO10 5DD, UK. b School of History, Classics and Archaeology, University of Edinburgh, UK cDepartment of Archaeology, University of Sheffield, UK d Laboratory for Artefact Studies, Faculty of Archaeology, Leiden University, The Netherlands e Alexander Keiller Museum, Avebury, Wiltshire, UK f Institute of Archaeology, University College London, London, UK g Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Department of Human Evolution, Deutscher Platz 6, 04103 Leipzig, Germany h English Heritage, 1 Waterhouse Square, 138-142 Holborn, London, UK Introduction Henges are distinctive monuments of the Late Neolithic in Britain, defined as ditched enclosures in which a bank is constructed outside the ditch. The largest is Durrington Walls (Fig 1), a 17ha monument near Stonehenge. Excavations at Durringon Walls from 1966 to 1968 revealed the remains of two timber circles, the Northern and Southern Circles, within the henge enclosure (Wainwright and Longworth, 1971). More recent excavations (2004-2007) have identified a settlement that pre-dates the henge by a few decades and is concurrent with the main construction phase of Stonehenge (Parker Pearson et al., 2007, Parker Pearson, 2007, Thomas, 2007). Middens and pits, with substantial quantities of animal bones, broken Grooved Ware ceramics and other food-related debris, accumulated quickly since the settlement has an estimated start of 2535-2475 cal BC (95% probability) and a use of 0-55 years (95% probability). -

Integrated Upper Ordovician Graptolite–Chitinozoan Biostratigraphy of the Cardigan and Whitland Areas, Southwest Wales

Geol. Mag. 145 (2), 2008, pp. 199–214. c 2007 Cambridge University Press 199 doi:10.1017/S0016756807004232 First published online 17 December 2007 Printed in the United Kingdom Integrated Upper Ordovician graptolite–chitinozoan biostratigraphy of the Cardigan and Whitland areas, southwest Wales THIJS R. A. VANDENBROUCKE∗†, MARK WILLIAMS‡, JAN A. ZALASIEWICZ‡, JEREMY R. DAVIES§ & RICHARD A. WATERS¶ ∗Research Unit Palaeontology, Ghent University, Krijgslaan 281/S8, 9000 Ghent, Belgium ‡Department of Geology, University of Leicester, University Road, Leicester LE1 7RH, UK §British Geological Survey, Kingsley Dunham Centre, Keyworth, Nottingham NG12 5GG, UK ¶Department of Geology, National Museum of Wales, Cathays Park, Cardiff CF10 3NP, UK (Received 26 January 2007; accepted 26 June 2007) Abstract – To help calibrate the emerging Upper Ordovician chitinozoan biozonation with the graptolite biozonation in the Anglo-Welsh, historical type basin, the graptolite-bearing Caradoc– Ashgill successions between Fishguard and Cardigan, and at Whitland, SW Wales, have been collected for chitinozoans. In the Cardigan district, finds of Armoricochitina reticulifera within strata referred to the clingani graptolite Biozone (morrisi Subzone), together with accessory species, indicate the Fungochitina spinifera chitinozoan Biozone, known from several Ordovician sections in northern England that span the base of the Ashgill Series. Tanuchitina ?bergstroemi, eponymous of the succeeding chitinozoan biozone, has tentatively been recovered from strata of Pleurograptus linearis graptolite Biozone age in the Cardigan area. The T. ?bergstroemi Biozone can also be correlated with the type Ashgill Series of northern England. Chitinozoans suggest that the widespread Welsh Basin anoxic–oxic transition at the base of the Nantmel Mudstones Formation in Wales, traditionally equated with the Caradoc–Ashgill boundary, is of Cautleyan (or younger Ashgill) age in the Cardigan area. -

Stonehenge Bibliography

Bibliography Abbot, M. and Anderson-Whymark, H., 2012. Anon., 2011a, Discoveries provide evidence of Stonehenge Laser Scan: archaeological celestial procession at Stonehenge. On-line analysis report. English Heritage project source available at: 6457. English Heritage Research Report http://www.birmingham.ac.uk/news/latest/ Series no. 32-2012, available at: 2011/11/25Nov-Discoveries-provide- http://services.english- evidence-of-a-celestial-procession-at- herita ge.org.uk/Resea rch Repo rtsPdf s/032_ Stonehenge.aspx (accessed 2 April 2012). 2012WEB.pdf Anon., 2011b, Stonehenge’s sister? Current Alexander, C., 2009, If the stones could speak: Archaeology, 260, 6–7. Searching for the meaning of Stonehenge. Anon., 2011c, Home is where the heath is. National Geographic, 213.6 (June 2008), Late Neolithic house, Durrington Walls. 34–59. Current Archaeology, 256, 42–3. Allen, S., 2008, The quest for the earliest Anon., 2011d, Stonehenge rocks. Current published image of Stonehinge (sic). Archaeology, 254, 6–7. Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural Anon., 2012a, Origin of some of the Bluestone History Magazine, 101, 257–9. debris at Stonehenge. British Archaeology, Anon., 2006, Excavation and Fieldwork in 123, 9. Wiltshire 2004. Wiltshire Archaeological Anon., 2012b, Stonehenge: sourcing the and Natural History Magazine, 99, 264–70. Bluestones. Current Archaeology, 263, 6– Anon., 2007a, Excavation and Fieldwork in 7. Wiltshire 2005. Wiltshire Archaeological Aronson, M., 2010, If stones could speak. and Natural History Magazine, 100, 232– Unlocking the secrets of Stonehenge. 39. Washington DC: National Geographic. Anon., 2007b, Before Stonehenge: village of Avebury Archaeological and Historical wild parties. Current Archaeology, 208, Research Group (AAHRG) 2001 17–21. -

Stonehenge and Avebury WHS Management Plan 2015 Summary

Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site Management Plan Summary 2015 Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site Management Plan Summary 2015 1 Stonehenge and Avebury World Heritage Site Vision The Stonehenge and Avebury World Heritage Site is universally important for its unique and dense concentration of outstanding prehistoric monuments and sites which together form a landscape without parallel. We will work together to care for and safeguard this special area and provide a tranquil, rural and ecologically diverse setting for it and its archaeology. This will allow present and future generations to explore and enjoy the monuments and their landscape setting more fully. We will also ensure that the special qualities of the World Heritage Site are presented, interpreted and enhanced where appropriate, so that visitors, the local community and the whole world can better understand and value the extraordinary achievements © K020791 Historic England © K020791 Historic of the prehistoric people who left us this rich legacy. Avebury Stone Circle We will realise the cultural, scientific and educational potential of the World Heritage Site as well as its social and economic benefits for the community. © N060499 Historic England © N060499 Historic Stonehenge in summer 2 Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site Management Plan Summary 2015 Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site Management Plan Summary 2015 1 World Heritage Sites © K930754 Historic England © K930754 Historic Arable farming in the WHS below the Ridgeway, Avebury The Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site is internationally important for its complexes of outstanding prehistoric monuments. Stonehenge is the most architecturally sophisticated prehistoric stone circle in the world, while Avebury is Stonehenge and Avebury were inscribed as a single World Heritage Site in 1986 for their outstanding prehistoric monuments the largest. -

Stonehenge OCR Spec B: History Around Us

OCR HISTORY AROUND US Site Proposal Form Example from English Heritage The Criteria The study of the selected site must focus on the relationship between the site, other historical sources and the aspects listed in a) to n) below. It is therefore essential that centres choose a site that allows learners to use its physical features, together with other historical sources as appropriate, to understand all of the following: a) The reasons for the location of the site within its surroundings b) When and why people first created the site c) The ways in which the site has changed over time d) How the site has been used throughout its history e) The diversity of activities and people associated with the site f) The reasons for changes to the site and to the way it was used g) Significant times in the site’s past: peak activity, major developments, turning points h) The significance of specific features in the physical remains at the site i) The importance of the whole site either locally or nationally, as appropriate j) The typicality of the site based on a comparison with other similar sites k) What the site reveals about everyday life, attitudes and values in particular periods of history l) How the physical remains may prompt questions about the past and how historians frame these as valid historical enquiries m) How the physical remains can inform artistic reconstructions and other interpretations of the site n) The challenges and benefits of studying the historic environment 1 Copyright © OCR 2018 Site name: STONEHENGE Created by: ENGLISH HERITAGE LEARNING TEAM Please provide an explanation of how your site meets each of the following points and include the most appropriate visual images of your site. -

Researching Stonehenge: Theories Past and Present

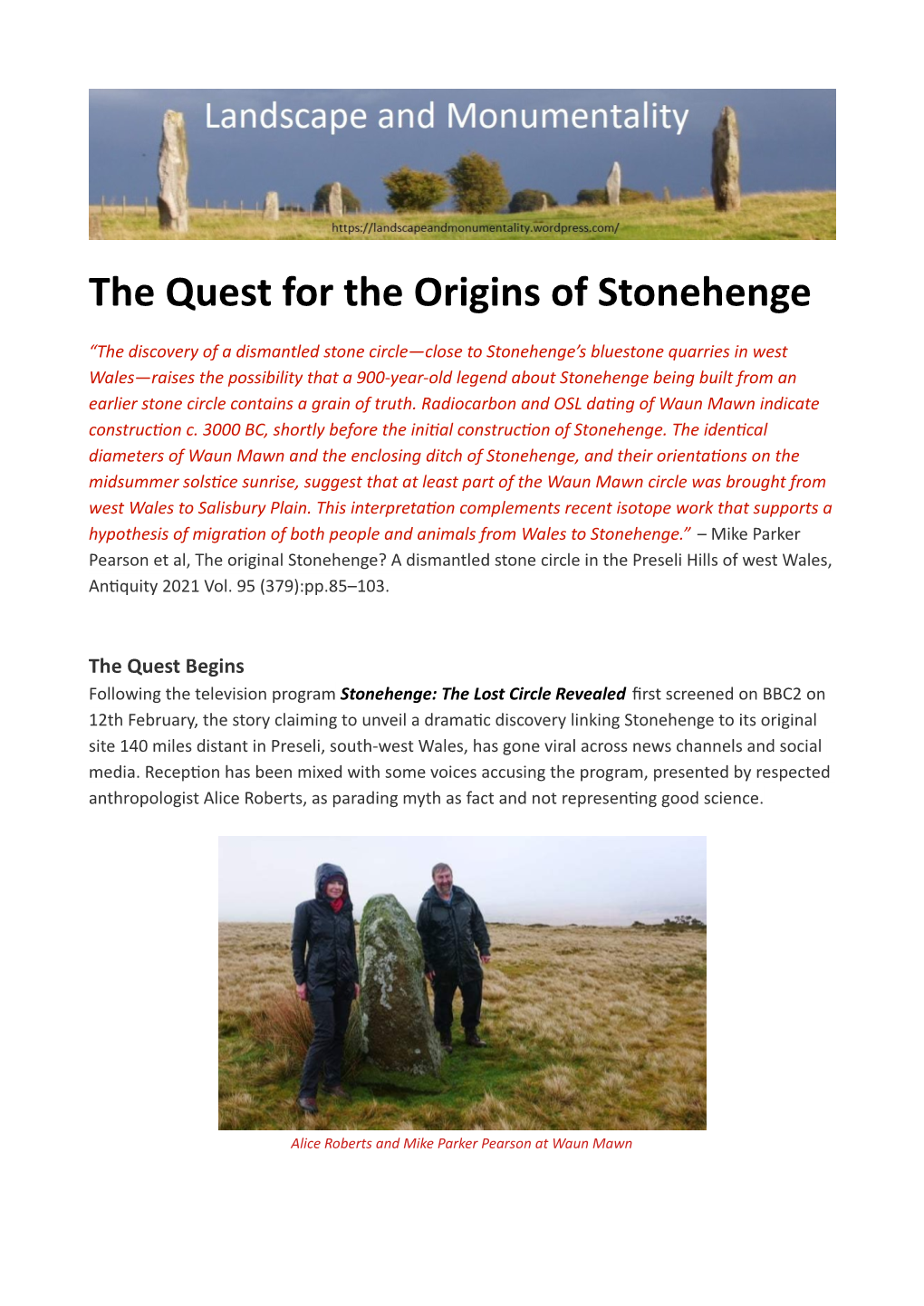

Parker Pearson, M 2013 Researching Stonehenge: Theories Past and Present. Archaeology International, No. 16 (2012-2013): 72-83, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/ai.1601 ARTICLE Researching Stonehenge: Theories Past and Present Mike Parker Pearson* Over the years archaeologists connected with the Institute of Archaeology and UCL have made substantial contributions to the study of Stonehenge, the most enigmatic of all the prehistoric stone circles in Britain. Two of the early researchers were Petrie and Childe. More recently, colleagues in UCL’s Anthropology department – Barbara Bender and Chris Tilley – have also studied and written about the monument in its landscape. Mike Parker Pearson, who joined the Institute in 2012, has been leading a 10-year-long research programme on Stonehenge and, in this paper, he outlines the history and cur- rent state of research. Petrie and Childe on Stonehenge William Flinders Petrie (Fig. 1) worked on Stonehenge between 1874 and 1880, publishing the first accurate plan of the famous stones as a young man yet to start his career in Egypt. His numbering system of the monument’s many sarsens and blue- stones is still used to this day, and his slim book, Stonehenge: Plans, Descriptions, and Theories, sets out theories and observations that were innovative and insightful. Denied the opportunity of excavating Stonehenge, Petrie had relatively little to go on in terms of excavated evidence – the previous dig- gings had yielded few prehistoric finds other than antler picks – but he suggested that four theories could be considered indi- vidually or in combination for explaining Stonehenge’s purpose: sepulchral, religious, astronomical and monumental. -

Professor Alice Roberts and Professor Iain Stewart Announced As New Patrons for the Natural Science Collections Association

PRESS RELEASE - 20 November 2013 for immediate release Professor Alice Roberts and Professor Iain Stewart Announced as New Patrons for the Natural Science Collections Association The Natural Science Collections Association (NatSCA) – the UK’s professional body for natural science collections and the people that work with them - is delighted to introduce its new patrons, the highly respected scientists Professor Alice Roberts and Professor Iain Stewart. Both are skilled communicators and strong advocates for the importance and incredible value of natural science collections. Professor Alice Roberts "Sometimes I think objects in museum collections are thought of as being only of historical interest. But natural science collections are not only valuable for their history; they also represent a vast source of new information for contemporary researchers. Not only that, but the objects in these collections hold the potential to inspire a new generation of natural scientists. I'm delighted to be a patron of NatSCA." Alice Roberts is the Professor of Public Engagement in Science at the University of Birmingham. Alice has written four popular science books about anatomy and human evolution. She has presented several science documentaries on the BBC, including Horizon episodes, The Incredible Human Journey, and Ice Age Giants. Professor Iain Stewart “Museums are more than mere time capsules - the displays, the specialists, even the buildings, are windows that throw light on how we see and make sense of the world around us. The collections are the keys to unlocking that. Through them we come close to places – and to times – that are otherwise exotic and distant. Dry labelled specimens spill out narratives and tales about scientific discovery that are too easily lost in the formal classroom. -

Mineral Reconnaissance Programme Report

_..._ Natural Environment Research Council -2 Institute of Geological Sciences - -- Mineral Reconnaissance Programme Report c- - _.a - A report prepared for the Department of Industry -- This report relates to work carried out by the British Geological Survey.on behalf of the Department of Trade I-- and Industry. The information contained herein must not be published without reference to the Director, British Geological Survey. I- 0. Ostle Programme Manager British Geological Survey Keyworth ._ Nottingham NG12 5GG I No. 72 I A geochemical drainage survey of the Preseli Hills, south-west Dyfed, Wales I D I_ I BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Natural Environment Research Council I Mineral Reconnaissance Programme Report No. 72 A geochemical drainage survey of the I Preseli Hills, south-west Dyfed, Wales Geochemistry I D. G. Cameron, BSc I D. C. Cooper, BSc, PhD Geology I P. M. Allen, BSc, PhD Mneralog y I H. W. Haslam, MA, PhD, MIMM $5 NERC copyright 1984 I London 1984 A report prepared for the Department of Trade and Industry Mineral Reconnaissance Programme Reports 58 Investigation of small intrusions in southern Scotland 31 Geophysical investigations in the 59 Stratabound arsenic and vein antimony Closehouse-Lunedale area mineralisation in Silurian greywackes at Glendinning, south Scotland 32 Investigations at Polyphant, near Launceston, Cornwall 60 Mineral investigations at Carrock Fell, Cumbria. Part 2 -Geochemical investigations 33 Mineral investigations at Carrock Fell, Cumbria. Part 1 -Geophysical survey 61 Mineral reconnaissance at the -

OUGS Journal 32

Open University Geological Society Journal Volume 32 (1–2) 2011 Editor: Dr David M. Jones e-mail: [email protected] The Open University Geological Society (OUGS) and its Journal Editor accept no responsibility for breach of copyright. Copyright for the work remains with the authors, but copyright for the published articles is that of the OUGS. ISSN 0143-9472 © Copyright reserved OUGS Journal 32 (1–2) Edition 2011, printed by Hobbs the Printers Ltd, Totton, Hampshire Committee of the Open University Geological Society 2011 Society Website: ougs.org Executive Committee President: Dr Dave McGarvie, Department of Earth Sciences, The Open University, Milton Keynes MK7 6AA Chairman: Linda Fowler Secretary: Sue Vernon, Treasurer: John Gooch Membership Secretary: Phyllis Turkington Newsletter Editor: Karen Scott Events Officer: Chris Arkwright Information Officer: vacant at time of going to press Branch Organisers East Anglia (EAn): Wendy Hamilton East Midlands (EMi): Don Cameron East Scotland (ESc): Stuart Swales Ireland (Ire): John Leahy London (Lon): Jenny Parry Mainland Europe (Eur): Elisabeth d'Eyrames Northumbria (Nor): Paul Williams North West (NWe): Mrs Jane Schollick Oxford (Oxf): Sally Munnings Severnside (Ssi): Janet Hiscott South East (SEa): Elizabeth Boucher South West (SWe): Chris Popham Walton Hall (WHa): Tom Miller Wessex (Wsx): Sheila Alderman West Midlands (WMi): Linda Tonkin West Scotland (WSc): Jacqueline Wiles Yorkshire (Yor): Geoff Hopkins Other officers (non-OUGSC voting unless otherwise indicated) Sales Administrator (voting OUGSC member ): vacant at time of going to press Administrator: Don Cameron Minutes Secretary: Pauline Kirtley Journal Editor: Dr David M. Jones Archivist/Reviews: Jane Michael Webmaster: Stuart Swales Deputy Webmaster: Martin Bryan Gift Aid Officer: Ann Goundry OUSA Representative: Capt. -

Pearson, M. P. & Al.: Stonehenge for the Ancestors, 1

PEARSON, M. P. & AL.: STONEHENGE FOR THE ANCESTORS, 1: LANDSCAPE AND MONUMENTS 1. Introduction The Stonehenge Riverside Project Background to the project Implications of the hypothesis Research aims M. Parker Pearson, J. Pollard, C. Richards, J. Thomas C. Tilley, K. Welham and P. Marshall 2. Fourth millennium BC beginnings: monuments in the landscape The landscape of the fourth millennium BC – (C. Tilley, W. Bennett and D. Field) Geophysical surveys of the Greater Cursus and Amesbury 42 long barrow – (K. Welham, C. Steele, L. Martin and A. Payne) 3. Fourth millennium BC beginnings: excavations of the Greater Cursus, Amesbury 42 long barrow and a tree-throw pit at Woodhenge The Greater Stonehenge Cursus – (J. Thomas) Amesbury 42 long barrow – (J. Thomas) Investigations of the buried soil beneath the mound of Amesbury 42 – (M.J. Allen) Stonehenge Lesser Cursus, Stonehenge Greater Cursus and the Amesbury 42 long barrow: radiocarbon dating – (P. D. Marshall, C. Bronk Ramsey and G. Cook) Antler artefact from the Greater Cursus and Amesbury 42 long barrow – (G. Davies) Pottery from the Greater Cursus and Amesbury 42 long barrow – (R. Cleal) Chalk artefact from the Greater Cursus – (A. Teather) Lithics from stratified contexts of the Greater Cursus – (B. Chan) Lithics from the ploughsoil of the Greater Cursus – (D. Mitcham) Lithics from stratified contexts of Amesbury 42 long barrow – (B. Chan) Human remains from Amesbury 42 long barrow and the Greater Cursus – (A. Chamberlain and C. Willis) Charred plant remains and wood charcoal from the Greater Cursus and Amesbury 42 long barrow – (E. Simmons) Woodhenge tree-throw pit – (J. Pollard) Pottery from the Woodhenge tree-throw pit – (Rosamund M.J. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 17 January 2014 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Towers, J. and Montgomery, J. and Evans, J. and Jay, M. and Pearson, M.P. (2010) 'An investigation of the origins of cattle and aurochs deposited in the Early Bronze Age barrows at Gayhurst and Irthlingborough.', Journal of archaeological science., 37 (3). pp. 508-515. Further information on publisher's website: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2009.10.012 Publisher's copyright statement: NOTICE: this is the author's version of a work that was accepted for publication in Journal of archaeological science. Changes resulting from the publishing process, such as peer review, editing, corrections, structural formatting, and other quality control mechanisms may not be reected in this document. Changes may have been made to this work since it was submitted for publication. A denitive version was subsequently published in Journal of archaeological science, 37,3, 20 2010, 10.1016/j.jas.2009.10.012 Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. -

Circular Route from Durrington Walls to Stonehenge

Circular route from Durrington Walls 3 Stonehenge Cottages, King to Stonehenge Barrows, Amesbury, Wiltshire SP4 7DD This walk explores two major historic monuments, Durrington TRAIL Walls and Stonehenge, in Walking the heart of the Stonehenge World Heritage Site. On this GRADE circular walk you will discover the Moderate landscape in its full glory from the Bronze Age barrows to the First DISTANCE World War military railway track, 5 miles (7.6km) as well as its diverse wildlife and plants. TIME 4 hours Terrain OS MAP Landranger 184; This circular walk follows hard tracks and gently sloping downs. Surfaces can be uneven, with potholes Explorer 130 or long tussocky grass. Dogs welcome on a lead and under control, as sheep and cattle graze the fields and there are ground-nesting birds. Contact Things to see 01980 664780 [email protected] Facilities Durrington Walls The old railway track The Avenue Have a look around you and Stonehenge Landscape has a This impressive bank and ditch http://nationaltrust.org.uk/walks appreciate the nature of this rich military history. The Lark Hill earthwork is more than 1.5 henge as an enclosed valley. Military Light Railway (LMLR) miles (2.5km) long. It may have If you were here over 4,500 line, ran through the landscape been the ceremonial route and years ago you would have seen from Amesbury to Larkhill and on entrance to the stone circle and In partnership with several shrines around the to the Stonehenge aerodrome recent excavations suggest it slopes, and Neolithic houses from 1914 until 1929.