A Potential Alternative Orodispersible Formulation to Prednisolone Sodium Phosphate Orally Disintegrating Tablets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pharmacy Phacts in This Issue Pharmd Candidates Discuss Oral Health and Preventing Eye Strain at Work

Pharmacy Phacts In this issue PharmD candidates discuss Oral Health and Preventing Eye Strain At Work Oral Health Landon Forrest Stewart, PharmD Candidate 2021 Why is Oral Health important? Oral health is an important part of our overall health. Oral health issues can cause oral pain, increased costs in healthcare, and less productivity. Recent developments in oral hygiene have led to improved outcomes for patients. Many oral health issues are still prevalent today, but the good news is that many are preventable with daily healthy habits. Healthy habits are required to maintain good oral health and many oral health issues are still prevalent today. One of the most common oral health problems is decay in the tooth also known as a cavity. The outer layer of the tooth is a tough mineral layer called the enamel. Bacteria group together on teeth to form plaques that can erode the enamel and the deeper layers of your teeth, causing cavities. Cavities are present and untreated in up to 26% up American adults. (1) If left untreated, they can lead to pain in the tooth and more severe infections known as an abscess. Another common oral health problem is gum disease. When bacteria group together on the teeth, it causes the immune system to respond and causes inflammation in the mouth. The initial inflammation is called gingivitis and makes your gums swell and bleed more easily. Untreated gingivitis can progress to a more severe gum disease called periodontitis. Periodontitis can damage the structure that holds your teeth in place and is a common cause of tooth loss. -

Study Protocol

RESEARCH PROTOCOL Project Title A multicenter, single blind, randomized controlled trial of virucidal effect of Polyvinylpyrrolidone-Iodine on SARS-CoV-2 as well as safety of its application on nasopharynx & oropharynx of COVID-19 positive patients BMRC Reg. No: 38624012021 Page-1/17 Project Title A multicenter, single blind, randomized controlled trial of virucidal effect of Polyvinylpyrrolidone- Iodine on SARS-CoV-2 as well as safety of its application on nasopharynx & oropharynx of COVID- 19 positive patients. Summary Povidone Iodine (Iodine with water soluble polymer Polyvinylpyrolidone) or PVP-I is a proven and time trusted antiseptic agent having best possible (99.99%) virucidal effect in it‟s only 0.23% concentration, against all viruses including SARS-Co, MERS-CoV; even in SARS-COV-2 due to it‟s nonspecific mode of action for virus killing and having no resistance [1,2]. Corona virus is transmitted by/via respiratory droplets or aerosol, produced from sneezing or coughing of infected persons to healthy individual through mouth and nose mainly [5, 6]. The routes of entry of coronavirus in human body are mouth, nose and eye. PVP-I products for gargling the throat and spraying or washing the nose may have a preventive effect on COVID-19 and if it is proved in this study following human trial, this will be a landmark research in COVID-19 pandemic. In line of this, PVP-I containing oro-nasal spray, proposed Bangasafe, which should be regarded as PONS (Povidone Iodine oro-nasal spray) in this protocol, has been developed and proposed to use against corona virus disease. -

Viscotears Liquid Gel Later Than Four Weeks After First Opening

Viscotears® Liquid Gel carbomer (polyacrylic acid) Patient Information Leaflet This product will be called Viscotears in this leaflet. Please read this leaflet carefully before you start to use Viscotears. It contains important information. Keep the leaflet in a safe place because you may want to read it again. Do not share these eye drops with anyone else just in case you have an eye infection which you could pass on. If you have any other questions, or if there is something you don’t understand, please ask your pharmacist. If any of the side effects gets serious, or if you notice any side effects not listed in this leaflet, please tell your doctor or pharmacist. In this leaflet: 1. What Viscotears is and what it’s used for 2. Things to consider before you start to use Viscotears 3. How to use Viscotears 4. Possible side effects 5. How to store Viscotears 6. Further information 1. What Viscotears is and what it’s used for Viscotears contains the active ingredient, carbomer (polyacrylic acid). Viscotears is used to make your eyes more comfortable when they feel dry. It is one of a group of eye drops called ‘artificial tears’. 2. Things to consider before you start to use Viscotears DO NOT use Viscotears if: If you are allergic to carbomer or any of the other ingredients of this medicine (listed in section 6). Take special care: In children and adolescents aged to 18 years, the safety and efficacy of Viscotears at the posology recommended in adults has been established by clinical experience, but no clinical trial data are available. -

Formulary Drug List

AMLODIPINE ORAL SUSPENSION Products Affected Step 2: • KATERZIA 1 MG/ML ORAL SUSPENSION Details Criteria PRIOR CLAIM FOR GENERIC AMLODIPINE TABLETS WITHIN THE PAST 120 DAYS. 1 ANTIBACTERIALS (EENT) Products Affected Step 2: • BESIVANCE 0.6 % EYE DROPS,SUSPENSION Details Criteria PRIOR CLAIM FOR FORMULARY VERSION OF CIPROFLOXACIN OPHTHALMIC OR OFLOXACIN OPHTHALMIC DROPS WITHIN THE LAST 120 DAYS. 2 ANTIDEPRESSANTS Products Affected Step 2: • FETZIMA 120 MG CAPSULE,EXTENDED RELEASE CAPSULE,EXTENDED RELEASE • FETZIMA 40 MG • FETZIMA 20 MG (2)-40 MG (26) CAPSULE,EXTENDED RELEASE CAPSULE,EXTENDED RELEASE,24 • FETZIMA 80 MG HR,DOSE PACK CAPSULE,EXTENDED RELEASE • FETZIMA 20 MG Details Criteria PRIOR CLAIM FOR TRINTELLIX AND VIIBRYD WITHIN THE PAST 365 DAYS. 3 ANTIPSYCHOTIC AGENTS Products Affected Step 2: • aripiprazole 10 mg disintegrating tablet • FANAPT 4 MG TABLET • aripiprazole 15 mg disintegrating tablet • FANAPT 6 MG TABLET • asenapine 10 mg sublingual tablet • FANAPT 8 MG TABLET • asenapine 2.5 mg sublingual tablet • SECUADO 3.8 MG/24 HOUR • asenapine 5 mg sublingual tablet TRANSDERMAL 24 HOUR PATCH • CAPLYTA 42 MG CAPSULE • SECUADO 5.7 MG/24 HOUR • clozapine 100 mg disintegrating tablet TRANSDERMAL 24 HOUR PATCH • clozapine 12.5 mg disintegrating tablet • SECUADO 7.6 MG/24 HOUR • clozapine 150 mg disintegrating tablet TRANSDERMAL 24 HOUR PATCH • clozapine 200 mg disintegrating tablet • VERSACLOZ 50 MG/ML ORAL • clozapine 25 mg disintegrating tablet SUSPENSION • FANAPT 1 MG TABLET • VRAYLAR 1.5 MG (1)-3 MG (6) • FANAPT 10 MG TABLET CAPSULES -

Handbook ESRA

TECHNIQUES HEAD & NECK 4 Intracranial surgery p. 3 Eye blocks p. 5 Face anatomy p. 16 Face particularity p. 23 Ophtalmic nerve blocks p. 27 Maxillary nerve blocks p. 33 Mandibular nerve blocks p. 46 THORAX & ABDOMEN 50 Epidural anaesthesia in Cardio-thoracic surgery p. 50 Ilioinguinal-Iliohypogastric block p. 55 Peri-umbilical & Rectus sheath block p. 57 Pudendal block p. 58 UPPER LIMB 61 Choice of a technique p. 61 Brachial plexus anatomy p. 65 Interscalen block p. 68 Supraclavicular blocks p. 73 Infraclavicular blocks p. 80 Axillary block p. 83 LOWER LIMB 90 Lumbar plexus block p. 90 Iliofascial block p. 100 Obturator block p. 102 Sciatic blocks o Sciatic blocks - parasacral nerve approach p. 109 o Sciatic blocks - posterior popliteal approach p. 115 Ankle blocks p. 119 AXIAL BLOCKS 123 Lumbar epidural p. 123 OBSTETRICS AXIAL BLOCKS 126 Epidural p. 126 PERIPHERAL BLOCKS Pudendal block p. 58 2 Aknowledgement The provenience of the materials included in this handbook is from the Learning Zone on the official site of “European Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Therapy”. http://www.esra-learning.com/ 2007 3 HEAD & TABLE OF CONTENTS NECK • Intracranial surgery • Eye blocks • Face anatomy • Face particularity • Ophtalmic nerve blocks • Maxillary nerve blocks • Mandibular nerve blocks • Cervical plexus blocks HEAD & INTRACRANIAL SURGERY NECK Paul J. Zetlaoui, M.D. Kremlin-Bicetre - France In intra-cranial neurosurgery, scalp infiltration aims to prevent systematic and cerebral hemodynamic variations, contemporary of skin incision. The potential morbidity of these hypertension-tachycardia episodes, even in patients profoundly anaesthetized, is secondary in the increase of the cerebral blood flow and in its deleterious consequences on intra-cranial pressure in these compromised patients. -

Can Pilocarpine Eye Drops Be Used to Treat Dry Mouth?

Page 1 of 5 Question: Can pilocarpine eye drops be used to treat dry mouth? July 2019 Summary Pilocarpine is not recommended as a first line treatment for dry mouth (xerostomia). However, saliva stimulants are generally more effective than saliva substitutes (unless a main salivary duct is blocked) 1, and are preferred by patients.2 Other saliva stimulants such as sugar-free chewing gum should be tried prior to the initiation of pilocarpine. Pilocarpine tablets (Salagen®) are unlicensed in Ireland but are licensed in the UK for the treatment of dry mouth following irradiation for head and neck cancer and for patients with Sjögren's syndrome.3 There is limited information available to support the oral use of pilocarpine eye drops as an alternative. The use of pilocarpine eye drops to treat a dry mouth is unlicensed. For cost/reimbursement reasons, pilocarpine eye drops administered orally are favored over the use of Salagen® oral tablets (unlicensed). A recommended dose of 5mg - 10mg three times daily of oral pilocarpine tablets is approximately equivalent to pilocarpine 4% w/v, 3 - 5 drops (6mg-10mg) taken orally three times daily. 1 - 6 Palliative Meds Info: Terms and Conditions The information outlined above is intended for healthcare professionals only. The information outlined above is believed to accurately reflect the medical literature at the time of writing. Healthcare professionals must use their own judgment to determine the accuracy and relevance of the information. See www.olh.ie for full terms and conditions. Page 2 of 5 Availability Pilocarpine tablets are indicated for the treatment of dry mouth following irradiation for head and neck cancer and for dry mouth and dry eyes in Sjogren’s syndrome. -

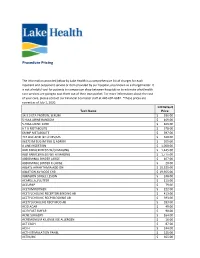

Procedure Pricing

Procedure Pricing The information provided below by Lake Health is a comprehensive list of charges for each inpatient and outpatient service or item provided by our hospital, also known as a chargemaster. It is not a helpful tool for patients to comparison shop between hospitals or to estimate what health care services are going to cost them out of their own pocket. For more information about the cost of your care, please contact our Financial Counselor staff at 440-602-6682. *These prices are correct as of July 1, 2020. LH Default Tech Name Price 14.3.3 ETA PROTEIN, SERUM $ 336.00 5 HIAA URINE RANDOM $ 169.00 5-HIAA URINE 24HR $ 169.00 6 T G METABOLITE $ 378.00 6MMP METABOLITE $ 397.00 7C4 BILE ACID BY LC MS/MS $ 468.00 96372 IM SUG IM SUB Q ADMIN $ 205.00 A LINE INSERTION $ 1,050.00 ABD PARACENTESIS W/O IMAGING $ 1,445.00 ABD PARACENTESIS WITH IMAGING $ 1,775.00 ABDOMINAL BINDER LARGE $ 107.00 ABDOMINAL BINDER X-LARGE $ 20.00 ABLATE ARRHYTHMIA ADD ON $ 10,525.00 ABLATION AV NODE CHB $ 19,955.00 ABRASION SINGLE LESION $ 248.00 ACAPELLA_FLUTTER $ 111.00 ACCUPAP $ 79.00 ACETAMINOPHEN $ 222.00 ACETYLCHOLINE RECEPTOR BINDING AB $ 413.00 ACETYLCHOLINE RECP BLOCKING AB $ 393.00 ACETYLOCHOLINE RECP MOD AB $ 393.00 ACID AGAR $ 49.00 ACID FAST SMEAR $ 90.00 ACNE SURGERY $ 164.00 ACREMONIUM KILIENSE IGE ALLERGEN $ 16.00 ACT EACH $ 87.00 ACTH $ 244.00 ACTH STIMULATION PANEL $ 225.00 ACTIN,IHC $ 365.00 ACTIVATED PROTEIN C $ 101.00 ACTV WOUND MGMT W/DEBRIDEMENT FIRST 20 SQ CM $ 179.00 ACUTE HEPATITIS PANEL $ 244.00 ADDL IV MED PUSH SAME DRUG $ 277.00 -

Consent to Medical -Surgical Procedure and Administration of Anesthesia

Consent to Medical -Surgical Procedure and Administration of Anesthesia Procedure Scheduled at: Springview Hospital Health South Other: _ Surgeon: Thomas G. Abell, MD unless noted otherwise here: Physician's Surgical Procedure Disclosure and Patients Consent TO THE PATIENT: You have the right to be informed about your condition and the recommended surgical, medical or diagnostic procedure so that you may make the decision whether or not to undergo the procedures after knowing the risks involved and any treatment alternatives available to you. This information is not meant to alarm you; it is an effort to make you better informed so that you may give or withhold your consent to the procedure. If you do not understand any of the information provided, ask your physician to explain it. 1. DIAGNOSIS: I (we) voluntarily request my physician, Thomas G. Abell, MD., and such associates, technical assistants, and other health care providers as they may deem necessary, to treat my CONDITION and perform procedure(s) PHACOEMULSIFICATION CATARACT EXTRACTION WITH INTRA-OCULAR LENS IMPLANTATION. This procedure, including, preoperative preparation, lab work (if needed), eye drop use/instillation, postoperative care, has been explained and reviewed with me. 2. PROCEDURE(S): I (we) understand that the following surgical procedure or procedures are planned for me on or about RIGHT EYE LEFT EYE . I voluntarily consent to and authorize this (these) PROCEDURE(S) because it : (PLEASE HAVE PT INITIAL NEXT TO THEIR SELECTION) __ Interferes with my ability to maintain -

Advanced Formulation Approaches for Ocular Drug Delivery: State-Of-The-Art and Recent Patents

pharmaceutics Review Advanced Formulation Approaches for Ocular Drug Delivery: State-Of-The-Art and Recent Patents Eliana B. Souto 1,2,*, João Dias-Ferreira 1 , Ana López-Machado 3,4, Miren Ettcheto 5,6, Amanda Cano 3,4,5, Antonio Camins Espuny 5,6 , Marta Espina 3,4 , Maria Luisa Garcia 3,4,5 and Elena Sánchez-López 1,3,4,5,* 1 Department of Pharmaceutical Technology, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Coimbra, 3000-458 Coimbra, Portugal 2 CEB—Centre of Biological Engineering, University of Minho, Campus de Gualtar 4710-057 Braga, Portugal 3 Department of Pharmacy, Pharmaceutical Technology and Physical Chemistry, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Barcelona, 08028 Barcelona, Spain 4 Institute of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology (IN2UB), University of Barcelona, 08028 Barcelona, Spain 5 Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Neurodegenerativas (CIBERNED), University of Barcelona, 08028 Barcelona, Spain 6 Department of Pharmacology, Toxicology and Therapeutic Chemistry, Faculty of Pharmacy and Food Sciences, University of Barcelona, 08028 Barcelona, Spain * Correspondence: ebsouto@ff.uc.pt (E.B.S.); [email protected] (E.S.-L.); Tel.: +351-239-488-400 (E.B.S.); +34-696-793-679 (E.S.-L.) Received: 6 August 2019; Accepted: 26 August 2019; Published: 6 September 2019 Abstract: The eye presents extensive perspectives and challenges for drug delivery, mainly because of the extraordinary capacity, intrinsic to this path, for drugs to permeate into the main circulatory system and also for the restrictions of the ocular barriers. Depending on the target segment of the eye, anterior or posterior, the specifications are different. The ocular route experienced in the last decades a lot of progresses related with the development of new drugs, improved formulations, specific-designed delivery and even new routes to administer a drug. -

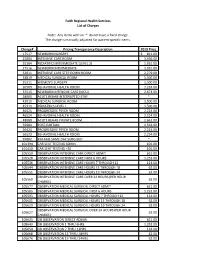

Faith Regional Health Services List of Charges Note: Any Items with an '*' Do Not Have a Fixed Charge. the Charge Is Manually A

Faith Regional Health Services List of Charges Note: Any items with an '*' do not have a fixed charge. The charge is manually adjusted for patient-specific items. Charge# Pricing Transparency Description 2019 Price 17517 NEWBORN NURSERY $ 821.00 22004 INTENSIVE CARE ROOM 3,456.00 25304 PEDIATRICS INTERMEDIATE (LEVEL 2) 1,931.00 27516 NEWBORN INTERMEDIATE 1,931.00 32011 INTENSIVE CARE STEP DOWN ROOM 2,279.00 34819 MEDICAL SURGICAL ROOM 1,500.00 35311 WOMEN'S SURGERY 1,500.00 36509 BEHAVORIAL HEALTH ROOM 2,224.00 37515 NEWBORN INTENSIVE CARE (NICU) 2,673.00 38000 ACUTE REHAB INTERRUPTED STAY * 42010 MEDICAL SURGICAL ROOM 1,500.00 45310 PEDIATRICS LEVEL 1 1,500.00 46425 PROGRESSIVE PSYCH ROOM 2,224.00 46524 BEHAVORIAL HEALTH ROOM 2,224.00 48009 ACUTE REHAB PRIVATE ROOM 1,662.00 55004 POST-PARTUM 1,532.00 56424 PROGRESSIVE PSYCH ROOM 2,224.00 56523 BEHAVORIAL HEALTH ROOM 2,224.00 99002 RM AMS SAME DAY SURG BED * 101394 CAR SEAT TESTING 60MIN. 101.00 101410 CAR SEAT TESTING +30 101.00 105510 OBSERVATION INTENSIVE CARE DIRECT ADMIT 621.00 105528 OBSERVATION INTENSIVE CARE FIRST 6 HOURS 1,252.00 105536 OBSERVATION INTENSIVE CARE HOURS 7 THROUGH 12 124.00 105544 OBSERVATION INTENSIVE CARE HOURS 13 THROUGH 18 62.00 105551 OBSERVATION INTENSIVE CARE HOURS 19 THROUGH 24 62.00 OBSERVATION INTENSIVE CARE OVER 24 HOURS (PER HOUR 105569 62.00 CHARGE) 105577 OBSERVATION MEDICAL SURGICAL DIRECT ADMIT 621.00 105585 OBSERVATION MEDICAL SURGICAL FIRST 6 HOURS 1,252.00 105593 OBSERVATION MEDICAL SURGICAL HOURS 7 THROUGH 12 124.00 105601 OBSERVATION MEDICAL SURGICAL HOURS 13 THROUGH 18 62.00 105619 OBSERVATION MEDICAL SURGICAL HOURS 19 THROUGH 24 62.00 OBSERVATION MEDICAL SURGICAL OVER 24 HOURS (PER HOUR 105627 62.00 CHARGE) 105635 OB OBSERVATION DIRECT ADMIN. -

Instilling Eye Drops

Instilling Eye Drops This material will help you understand eye drops and how to properly use them. What are the different types of eye drops? There are two different kinds of eye drops for patient use: over-the- counter and prescription. You can buy over-the-counter eye drops without a prescription from your doctor, but you still need to use them as directed. Artificial tears are one kind of over-the-counter eye drops, and are used to soothe dry or irritated eyes. Your doctor may also prescribe steroid eye drops, eye drops to treat infections, or those that treat glaucoma. When using eye drops, you should always follow your doctor’s directions and those written on the package. How do I insert eye drops? Many people find it easiest to put in their eye drops in front of a mirror. To insert eye drops into your eyes, follow these steps: 1. Before using your eye drops, wash your hands. 2. Remove the cap. Do not touch the tip of the bottle. 3. Slightly tilt your head back. Kellogg Eye Center – Glaucoma Clinic Instilling Eye Drops 1 4. Pull your lower eyelid down with your index finger to make a “pocket” with your lower lid, as seen in Picture 1. 5. Hold the tip of the bottle directly over this “pocket”. 6. While looking up, let the eye drop fall into the “pocket”. (Do not touch the bottle to your eye or Picture 1 eyelid.) 7. Close your eyes. 8. Using your finger, apply pressure where the lids meet the nose with your eyes closed, as seen in Picture 2. -

Monophasic Liquid Dosage Form

Contents • Introduction • Classification of Monophasic liquid • Formulation Consideration • Manufacturing Consideration • Recent advance in monophasic liquid • Recent approach in monophasic liquid formulation • Conclusion • Recommendation Introduction • Monophasic dosage form refers to liquid preparation containing two or more components in one phase system, it is represent by true solution. • A true solution is a clear homogenous mixture that is prepared by dissolving solute in a suitable solvent. • The component of the solution which is present in a large quantity is known as “SOLVENT” where as the component present in small quantity is termed as “SOLUTE”. Advantage • It is easier to swallow, therefore easier for children and old age people. • Facilitate absorption of drug faster than solid dosage form as drug is already in solution form. • It is homogenous therefore give uniform dose than suspension or emulsion which need shaking. • Simple and fast to formulate • It can be administered by various routes : Oral, Parenteral (injection),enema for rectal use, otic(ear), nasal and ophthalmic preparation. Disadvantage • They are bulky, so difficult to transport and store. • Water is commonly use vehicle, which is prone to microbial growth. So addition of preservative is needed. • When expose to direct sunlight it may undergo hydrolysis, so need to store in cool and dark place. • Drug stability reduce by hydrolysis or oxidation. So, they have shorter expire date than solid dosage form. • Other major sign of drug instability are color change, Precipitation, microbial growth etc. Classification Liquids meant for internal administrations • Syrup : Aqueous preparations of 60% to 85% sucrose with or without flavoring agents and medicinal substances. e.g.