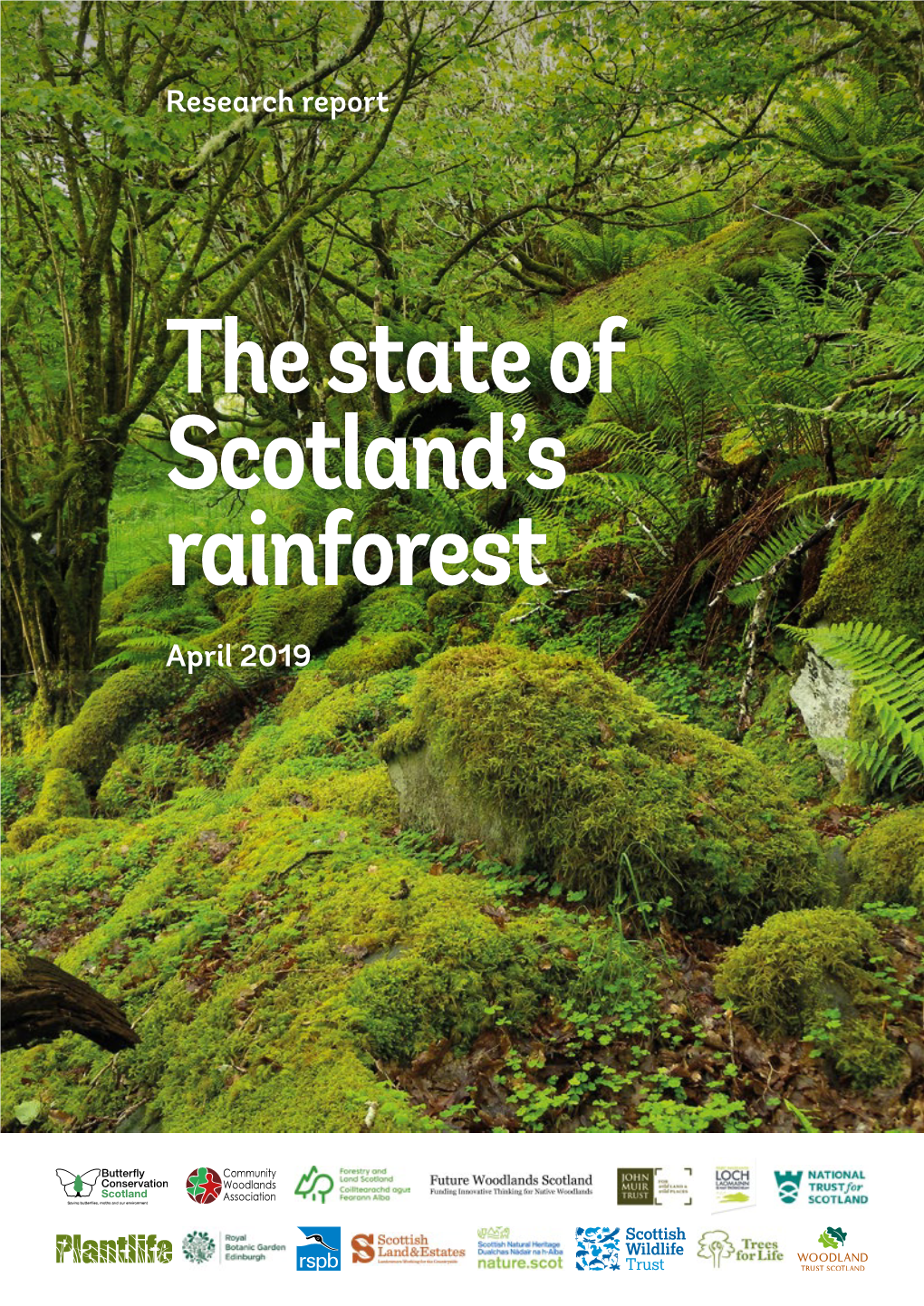

Scotland's Temperate Rainforest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chilterns Ancient Woodland Survey Appendix: South Bucks District

Ancient Woodland Inventory for the Chilterns Appendix - South Bucks District Chiltern Woodlands CONSERVATION BOARD Project Chiltern District Council WYCOMBE DISTRICT COUNCIL an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty 1. Introduction his appendix summarises results from the Chilterns Ancient Woodland Survey for the whole of South Bucks District in the County of Buckinghamshire (see map 1 for details). For more information on the project and Tits methodology, please refer to the main report, 1which can be downloaded from www.chilternsaonb.org The Chilterns Ancient Woodland Survey area includes parts of Buckinghamshire, Bedfordshire, Hertfordshire and Oxfordshire. The extent of the project area included, but was not confined to, the Chilterns Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB). 2 The work follows on from previous revisions in the South East. The Chilterns survey was hosted by the Chilterns Conservation Board with support from the Chiltern Woodlands Project, Thames Valley Environmental Records Centre (TVERC) and Surrey Biodiversity Information Centre (SBIC). The work was funded by Buckinghamshire County Council, Chilterns Conservation Board, Chiltern District Council, Dacorum Borough Council, Forestry Commission, Hertfordshire County Council, Natural England and Wycombe District Council. Map 1: Project aims The Survey Area, showing Local Authority areas covered and the Chilterns AONB The primary aim of the County Boundaries survey was to revise and Chilterns AONB update the Ancient Entire Districts Woodland Inventory and Chiltern District -

Ancient Woodland Restoration Phase Three: Maximising Ecological Integrity

Practical Guidance Module 5 Ancient woodland restoration Phase three: maximising ecological integrity Contents 1 Introduction ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������3 2 How to maximise ecological integrity ��������������������������������������4 2�1 More ‘old-growth characteristics’ ������������������������������������4 2�1�1 More old trees ���������������������������������������������������������5 • Let natural processes create old trees • Use management interventions to maintain and develop more old trees 2�1�2 More decaying wood����������������������������������������������8 • Let natural processes create decaying wood • Use management interventions to maintain and create more decaying wood • Veteranisation techniques can create wood- decay habitats on living trees 2�1�3 Old-growth groves �����������������������������������������������15 • Use minimum intervention wisely to help develop old-growth characteristics 2�2 Better space and dynamism �������������������������������������������17 2�2�1 Let natural processes create space and dynamism ��������������������������������������������������17 2�2�2 Manage animals as an essential natural process ������������������������������������������������������ 22 • Consider restoration as more than just managing the trees 2�2�3 Use appropriate silvicultural interventions ��� 28 • Use near-to-nature forestry to create better space and dynamism 2�3 Better physical health ����������������������������������������������������� 33 2�3�1 Better water �������������������������������������������������������� -

A Provisional Inventory of Ancient and Long-Established Woodland in Ireland

A provisional inventory of ancient and long‐established woodland in Ireland Irish Wildlife Manuals No. 46 A provisional inventory of ancient and long‐ established woodland in Ireland Philip M. Perrin and Orla H. Daly Botanical, Environmental & Conservation Consultants Ltd. 26 Upper Fitzwilliam Street, Dublin 2. Citation: Perrin, P.M. & Daly, O.H. (2010) A provisional inventory of ancient and long‐established woodland in Ireland. Irish Wildlife Manuals, No. 46. National Parks and Wildlife Service, Department of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government, Dublin, Ireland. Cover photograph: St. Gobnet’s Wood, Co. Cork © F. H. O’Neill The NPWS Project Officer for this report was: Dr John Cross; [email protected] Irish Wildlife Manuals Series Editors: N. Kingston & F. Marnell © National Parks and Wildlife Service 2010 ISSN 1393 – 6670 Ancient and long‐established woodland inventory ________________________________________ CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 2 INTRODUCTION 3 Rationale 3 Previous research into ancient Irish woodland 3 The value of ancient woodland 4 Vascular plants as ancient woodland indicators 5 Definitions of ancient and long‐established woodland 5 Aims of the project 6 DESK‐BASED RESEARCH 7 Overview 7 Digitisation of ancient and long‐established woodland 7 Historic maps and documentary sources 11 Interpretation of historical sources 19 Collation of previous Irish ancient woodland studies 20 Supplementary research 22 Summary of desk‐based research 26 FIELD‐BASED RESEARCH 27 Overview 27 Selection of sites -

Status and Development of Old-Growth Elements and Biodiversity During Secondary Succession of Unmanaged Temperate Forests

Status and development of old-growth elementsand biodiversity of old-growth and development Status during secondary succession of unmanaged temperate forests temperate unmanaged of succession secondary during Status and development of old-growth elements and biodiversity during secondary succession of unmanaged temperate forests Kris Vandekerkhove RESEARCH INSTITUTE NATURE AND FOREST Herman Teirlinckgebouw Havenlaan 88 bus 73 1000 Brussel RESEARCH INSTITUTE INBO.be NATURE AND FOREST Doctoraat KrisVDK.indd 1 29/08/2019 13:59 Auteurs: Vandekerkhove Kris Promotor: Prof. dr. ir. Kris Verheyen, Universiteit Gent, Faculteit Bio-ingenieurswetenschappen, Vakgroep Omgeving, Labo voor Bos en Natuur (ForNaLab) Uitgever: Instituut voor Natuur- en Bosonderzoek Herman Teirlinckgebouw Havenlaan 88 bus 73 1000 Brussel Het INBO is het onafhankelijk onderzoeksinstituut van de Vlaamse overheid dat via toegepast wetenschappelijk onderzoek, data- en kennisontsluiting het biodiversiteits-beleid en -beheer onderbouwt en evalueert. e-mail: [email protected] Wijze van citeren: Vandekerkhove, K. (2019). Status and development of old-growth elements and biodiversity during secondary succession of unmanaged temperate forests. Doctoraatsscriptie 2019(1). Instituut voor Natuur- en Bosonderzoek, Brussel. D/2019/3241/257 Doctoraatsscriptie 2019(1). ISBN: 978-90-403-0407-1 DOI: doi.org/10.21436/inbot.16854921 Verantwoordelijke uitgever: Maurice Hoffmann Foto cover: Grote hoeveelheden zwaar dood hout en monumentale bomen in het bosreservaat Joseph Zwaenepoel -

Ancient Hampshire Forests and the Geological Conditions of Their Growth

40 ANCIENT HAMPSHIRE FORESTS AND THE GEOLOGICAL CONDITIONS OF THEIR GROWTH. ,; BY T. W, SHORE, F.G.S., F.C.S. If we examine the map oi Hampshire with the view of considering what its condition, probably was' at that time which represents the dawn of history, viz., just before the Roman invasion, and consider what is known of the early West Saxon settlements in the county, and of the earthworks of their Celtic predecessors, we can .scarcely fail to come to the conclusion that in pre-historic Celtic time it must have been almost one continuous forest broken only by large open areas of chalk down land, or by the sandy heaths of the Bagshot or Lower Greensand formations. On those parts of the chalk down country which have only a thin soil resting on the white chalk, no considerable wood could grow, and such natural heath and furze land as the upper Bagshot areas of the New Forest, of Aldershot, and Hartford Bridge Flats, or the sandy areas of the Lower Bagshot age, such as exists between Wellow and Bramshaw, or the equally barren heaths of the Lower Greensand age, in the neighbourhood of Bramshot and Headley, must always have been incapable of producing forest growths. The earliest traces of human settlements in this county are found in and near the river valleys, and it as certain as any matter which rests on circumstantial evidence, can be that the earliest clearances in the primaeval woods of Hampshire were on the gently sloping hill sides which help to form these valleys, and in those dry upper vales whicli are now above the permanent sources of the rivers. -

BLS Bulletin 102 Summer 2008.Pdf

BRITISH LICHEN SOCIETY OFFICERS AND CONTACTS 2008 PRESIDENT P.W. Lambley MBE, The Cottage, Elsing Road, Lyng, Norwich NR9 5RR, email [email protected] VICE-PRESIDENT S.D. Ward, 14 Green Road, Ballyvaghan, Co. Clare, Ireland, email [email protected] SECRETARY Post Vacant. Correspondence to Department of Botany, The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD. TREASURER J.F. Skinner, 28 Parkanaur Avenue, Southend-on-sea, Essex SS1 3HY, email [email protected] ASSISTANT TREASURER AND MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY D. Chapman, The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, email [email protected] REGIONAL TREASURER (Americas) Dr J.W. Hinds, 254 Forest Avenue, Orono, Maine 04473- 3202, USA. CHAIR OF THE DATA COMMITTEE Dr D.J. Hill, email [email protected] MAPPING RECORDER AND ARCHIVIST Prof. M.R.D.Seaward DSc, FLS, FIBiol, Department of Environmental Science, The University, Bradford, West Yorkshire BD7 1DP, email [email protected] DATABASE MANAGER Ms J. Simkin, 41 North Road, Ponteland, Newcastle upon Tyne, Northumberland NE20 9UN, email [email protected] SENIOR EDITOR (LICHENOLOGIST) Dr P.D.Crittenden, School of Life Science, The University, Nottingham NG7 2RD, email [email protected] BULLETIN EDITOR Dr P.F. Cannon, CABI Europe UK Centre, Bakeham Lane, Egham, Surrey TW20 9TY, email [email protected] CHAIR OF CONSERVATION COMMITTEE & CONSERVATION OFFICER B.W. Edwards, DERC, Library Headquarters, Colliton Park, Dorchester, Dorset DT1 1XJ, email [email protected] CHAIR OF THE EDUCATION AND PROMOTION COMMITTEE Dr B. Hilton, email [email protected] CURATOR R.K. -

Managing Deadwood in Forests and Woodlands

Practice Guide Managing deadwood in forests and woodlands Practice Guide Managing deadwood in forests and woodlands Jonathan Humphrey and Sallie Bailey Forestry Commission: Edinburgh © Crown Copyright 2012 You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit: www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence or write to the Information Policy Team at The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or e-mail [email protected]. This publication is also available on our website at: www.forestry.gov.uk/publications First published by the Forestry Commission in 2012. ISBN 978-0-85538-857-7 Jonathan Humphrey and Sallie Bailey (2012). Managing deadwood in forests and woodlands. Forestry Commission Practice Guide. Forestry Commission, Edinburgh. i–iv + 1–24 pp. Keywords: biodiversity; deadwood; environment; forestry; sustainable forest management. FCPG020/FC-GB(ECD)/ALDR-2K/MAY12 Enquiries relating to this publication should be addressed to: Forestry Commission Silvan House 231 Corstorphine Road Edinburgh EH12 7AT 0131 334 0303 [email protected] In Northern Ireland, to: Forest Service Department of Agriculture and Rural Development Dundonald House Upper Newtownards Road Ballymiscaw Belfast BT4 3SB 02890 524480 [email protected] The Forestry Commission will consider all requests to make the content of publications available in alternative formats. Please direct requests to the Forestry Commission Diversity Team at the above address, or by email at [email protected] or by phone on 0131 314 6575. Acknowledgements Thanks are due to the following contributors: Fred Currie (retired Forestry Commission England); Jill Butler (Woodland Trust); Keith Kirby (Natural England); Iain MacGowan (Scottish Natural Heritage). -

Ancient Woods a Guide for Woodland Owners and Managers

Ancient Woods A guide for woodland owners and managers The Woodland Trust was founded in 1972 and is the UK’s leading woodland conservation organisation. The Trust achieves its aims through a combination of acquiring woodland and sites for planting and through advocacy of the importance of protecting ancient woodland, enhancing its biodiversity, expanding native woodland cover and increasing public enjoyment of woodland. The Trust relies on the generosity of the public, industry, commerce and agencies to carry out its work. To find out how you can help, and about membership details, please contact one of the addresses below. The Woodland Trust (Registered Office) Autumn Park, Dysart Road Grantham Lincolnshire NG31 6LL Telephone: 01476 581111 The Woodland Trust Wales/Coed Cadw 3 Cooper’s Yard, Curran Road Cardiff CF10 5NB Telephone: 08452 935860 The Woodland Trust Scotland South Inch Business Centre, Shore Road, Perth PH2 8BW Telephone: 01738 635829 The Woodland Trust in Northern Ireland 1 Dufferin Court, Dufferin Avenue Bangor County Down BT20 3BX Telephone: 028 9127 5787 Website: www.woodlandtrust.org.uk This report should be referenced as: The Woodland Trust 2009 Ancient Woods: A guide for woodland owners and managers. (www.woodlandtrust.org.uk/publications) © The Woodland Trust, 2009 The Woodland Trust logo is a registered trademark. Registered Charity nos. 294344 and SC038885. A non-profit making company limited by guarantee. Registered in England no. 1982873. Cover photo: WTPL/Fran Hitchinson 4159 09/09 r e k c e B d Ancient woods and their special value Ancient woods and land management r a h c i R / L P Ancient woods and other places with an unbroken history of tree cover are uniquely For many landowners ancient woods form part of a (1) Identify the special features of these sites; and T W landholding that is also a business. -

Woodland & Trees

Woodland & Trees Headlines • Using our standard methods, 14.8% or 5,454ha of Sheffield is classed as woodland. Data gathered during the recent iTree project suggest even greater coverage of 5,946ha or 16.2%, substantially higher than the national figure of 10%. Total tree cover for the Sheffield district, calculated by iTree, is 18.4%. • 23.5% of Sheffield’s lowland woodland is categorised as ancient semi-natural woodland (ASNW) or plantations on ancient woodland sites (PAWS). This covers 3.5% of the Sheffield district and is higher than the figure of 2.3% for the UK. • Sheffield’s woodlands are a valuable recreational resource. Ninety-four percent of people have access to a large woodland (20ha) within 4km of their residence and nearly half of Sheffield’s population has access to a 2ha woodland within 500m. • Over half of Sheffield’s woodlands are covered by designations such as Local Wildlife Sites (LWSs) and 63% of land with LWS designation is woodland. Most sites are improving; over 70% of woodland habitat within LWSs is in positive conservation management. Over 92% of ancient woodland is covered by a site designation. • Compared to UK trends, bird species considered in the UK Biodiversity Indicator ‘C5b: woodland birds’ are doing well, particularly woodland generalists, indicating the good health of Sheffield’s woodlands. • Threats to woodlands in Sheffield include habitat fragmentation, damage from recreation and spread of invasive species from gardens. Continued improvements in woodland management, including the input of local groups, can help tackle this. Broadleaved woodland © Guy Edwardes/2020VISION 31 Introduction Sheffield is considered to be the most wooded city in Britain and one of the most wooded cities in Europe with a total tree cover of 18.4% ,1,2 . -

FOREST FLORA Woodland Conservation News • Spring 2018

Wood Wise FOREST FLORA Woodland Conservation News • Spring 2018 QUESTIONING SURVEYING TIME FOR WOODLAND ANCIENT & RESTORING A BUNCE FLORA WOODLAND WOODLAND WOODLAND FOLKLORE INDICATORS FLORA RESURVEY & REMEDIES CONTENTS Smith / Georgina WTML 3 4 8 11 16 20 22 24 Introduction Spring is probably the best time to appreciate woodland The Woodland Trust’s Alastair Hotchkiss focuses on the ground flora. The warming temperatures encourage restoration of plantations on ancient woodland sites. 25 shoots to burst from bulbs, breaking through the soil Gradual thinning and natural regeneration of native trees Introduction to reach the sunlight not yet blocked out by leaves that can allow sunlight to reach the soil again and enable the 3 will soon fill the tree canopy. Their flowers bring colour return of wildflowers surviving in the seed bank. to break the stark winter and inspire hope in many that Questioning ancient woodland indicators The Woodland Survey of Great Britain 1971-2001 4 see them. recorded a change and loss in broadleaf woodland The species of flora covered in this issue are vascular ground flora species. The driver was thought to be a plants found on the woodland floor layer. Vascular plants 8 Trouble for bluebells? reduction in the use and management of woods. This have specialised tissues within their form that carry finding encouraged an increase in management. Several The world beneath your feet water and nutrients around their stems, leaves and other experts involved look at this and the potential for a future 11 structures, which allow them to grow taller than non- resurvey to analyse the current situation. -

Whgt Bulletin Lxii March 2012

welsh historic gardens trust ~ ymddiriedolaeth gerddi hanesyddol cymru whgt bulletin lxii march 2012 Troy House from the Wye Bridge by I Smith c.1680-90 shows a double avenue of trees. The collection of the Duke of Beaufort. Tree Avenues by Glynis Shaw Last August the National Trust began to survey its near Newport in South Wales is an example of an tree avenues. The National Trust has some 500 tree avenue in the forest environment. avenues in their care. However, many tree avenues Later, lines of trees were deliberately planted to are outside the care of the NT and it might be frame a house and to extend the formal design of interesting to survey such tree avenues in Wales. the garden into the parkland. These avenues Avenues are among the very oldest of landscape became extremely important in the structure of features with avenues of stone animals lining the early landscape design. Troy House near Mon- way to the Ming emperor’s tombs north of Beijing. In mouth, had a new front built in the late seven- Egypt a two mile avenue of ram headed sphinxes of teenth century for Charles Somerset, Marquis of the god Amun protecting a figure of Ramses II Worcester, son of Henry the First Duke of Beau- between its paws, links Luxor to the Karnak temple. fort. Troy was once framed by a double avenue In Britain the Spanish Chestnut avenue at Croft planted between the 1660s and 1706. The paint- Castle, Herefordshire, was planted with seeds from ing by J. Smith c.1720 shows the avenue leading the Armada wrecks in 1592 making it one of the old- from the main entrance of the house to the conflu- est tree avenues in Britain. -

Reforesting Britain

REFORESTING BRITAIN Why natural regeneration should be our default approach to woodland expansion Reforesting Britain: Why natural regeneration should be our default approach to woodland expansion CONTENTS Executive Summary 3 1. Introduction 5 2. Natural regeneration: Lessons from around the world 7 Natural regeneration will happen on a large scale if we allow it 8 Natural regeneration: Process and pace are complex and unpredictable 9 Natural regeneration brings biodiversity and climate benefits 11 3. Case studies of natural regeneration 13 Case study 1: Learning from south-west Norway 13 Case study 2: Natural regeneration in the uplands and highlands 14 Case study 3: Extending Britain’s rare rainforests 15 Case study 4: Natural regeneration in the lowlands – The Knepp Estate 16 Case study 5: Learning to love scrub 17 4. Key factors influencing natural regeneration 18 5. Natural regeneration hierarchy: A practical three-step model 22 6. Conclusion: Implications for future policy and practice 25 Appendix 1: Glossary of terms 27 References 28 Natural regeneration: The regeneration of trees and woodland through natural processes (e.g. seed dispersal) as opposed to planting by people. It may be assisted by human intervention, such as by scarification or fencing to protect against wildlife damage or domestic animal grazing. Cover image: Rich Atlantic oakwood in summer, Taynish National Nature Reserve Photography: Peter Cairns/scotlandbigpicture.com Rewilding Britain | www.rewildingbritain.org.uk 2 Reforesting Britain: Why natural regeneration should be our default approach to woodland expansion EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Trees should be abundant in the British landscape, The exact trajectory of re-vegetation (in terms of interspersed with meadows, scrub, wetlands, bog species mix, location and density) is difficult to predict and other habitats.