Redalyc.Different Motor Patterns in Basketball Depending on Gender?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WMU Sasakawa Fellows' Network Meeting in the East European

WMU Sasakawa Fellows’ Network Meeting in the East European, Middle Eastern, and North African Regions January 28th - February 1st, 2018 Novotel London West Hotel, London, United Kingdom Hosted and Organized by “Friends of WMU, Japan” Secretariat in Cooperation with The Nippon Foundation and U.K. Sasakawa Fellows Contents Contents Resolution ……………………………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Various Photos ………………………………………………………………………………………………… 5 Program Schedule …………………………………………………………………………………………… 13 Opening Session ……………………………………………………………………………………………… 19 1. Welcome Speech …………………………………………………………………………………… 21 (Sandra Rita ALLNUTT Brazil, 1999) 2. Opening Remarks ………………………………………………………………………………… 22 (Tsutomu AKITA Senior Specialist, Ocean Policy Research Institute, the Sasakawa Peace Foundation) Discussion on the WMU Sasakawa Fellows’ Network ……………………………………………………… 25 1. Procedure to become a candidate and benefit of being Sasakawa fellow. ………………………… 27 2. Mutual Communication. …………………………………………………………………………… 29 3. NEWSLETTER …………………………………………………………………………………… 31 4. Expansion of the Network ………………………………………………………………………… 33 Exchange of Maritime Information ………………………………………………………………………… 35 1. Update on WMU …………………………………………………………………………………… 37 (Ms. Susan Jackson, Registrar, World Maritime University) 2. Workshop Discussion Items ………………………………………………………………………… 39 (Amr Moneer IBRAHIM, Egypt 2013) 3. Role of The Human Element ……………………………………………………………………… 45 (Aynur MAHARRAMOVA, Azerbaijan 2017) 4. Maritime Education & Training in Ukraine ………………………………………………………… 49 (Igor -

Técnicas De Análisis En Estudios Observacionales En Ciencias Del Deporte

Cuadernos de Psicología del Deporte, vol. 15, 1, 13-30 © Copyright 2015: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Murcia Recibido: 18/07/2014 Murcia (España) Aceptado: 24/11/2014 ISSN edición impresa: 1578-8423 ISSN edición web ( http://revistas.um.es/cpd ): 1989-5879 Técnicas de análisis en estudios observacionales en ciencias del deporte Data analysis techniques in observational studies in sport sciences Técnicas de ciências estudos de análise de observacionais no sporte M. Teresa Anguera 1 y Antonio Hernández-Mendo 2 1 Universidad de Barcelona y 2 Universidad de Málaga Resumen: En este trabajo introductorio del número monográ&co Análisis and speci&cally when it implies that some aims are complementary; (3) de datos en estudios observacionales de Ciencias del Deporte (1): Avances tec- to contribute to technologic and software development, that itself it’s very nológicos y analíticos , se realiza –desde la lógica del método cienti&co y sus rellevant, and also we should move forward the creation of computerized distintas fases- un trazado de las diversas técnicas de análisis de uso en Me- plattforms; (4) to take advantage of the rellevance of the power and the todología Observacional (MO) y su importancia en el ámbito del Deporte. consistency of mixed methods Se realiza una revisión en la cual los diseños observacionales condicionan Keywords: Observational methodology, observational designs, kind of la pauta de análisis, y que ilustraremos citando los principales trabajos que data, analytic techniques, software. conforman cada uno -

Universidade Federal Do Rio Grande Do Sul Escola De Educação Física

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL ESCOLA DE EDUCAÇÃO FÍSICA Lucas Boeira ANÁLISE DE PADRÕES-T NO ESPORTE: UMA REVISÃO Porto Alegre 2017 Lucas Boeira ANÁLISE DE PADRÕES-T NO ESPORTE: UMA REVISÃO Trabalho de conclusão de curso de graduação apresentado à Escola de Educação Física, Fisioterapia e Dança da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Licenciado em Educação Física. Orientador: Prof. Dr. José Cícero Moraes Porto Alegre 2017 1 ÍNDICE DE FIGURAS Figura 1. Processo de seleção de trabalhos. ............................................................10 Figura 2. Gráfico por fatias das sub-áreas. ...............................................................11 Figura 3. Frequência de publicações por ano. ..........................................................12 Figura 4. Registro hipotético de comportamentos ou eventos ao longo de um período de tempo. ..................................................................................................................13 Figura 5. Comparação entre seleções nacionais e clubes. .......................................21 Figura 6. Dimensões usuais de uma quadra de futsal e códigos de cada zona........33 Figura 7. Primeiro padrão-T de gol............................................................................33 Figura 8. Segundo padrão-T de gol...........................................................................34 2 SUMÁRIO ÍNDICE DE FIGURAS .......................................................................................... -

'I Am Not a Foreigner Anymore': a Microsociological Study of the Experiences of Brazilian Futsal Players in European Leagues Movimento, Vol

Movimento ISSN: 0104-754X [email protected] Escola de Educação Física Brasil Dimeo, Paul; Vasconcellos Ribeiro, Carlos Henrique de 'I Am Not A Foreigner Anymore': a microsociological study of the experiences of brazilian futsal players in european leagues Movimento, vol. 15, núm. 2, abril-junio, 2009, pp. 33-44 Escola de Educação Física Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=115315433003 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative ‘I Am Not A Foreigner Anymore’: a micro- sociological study of the experiences of brazilian futsal players in european leagues Paul Dimeo* Carlos Henrique de Vasconcellos Ribeiro** Abstract: This paper represents the first stage of a longer term study of sport and migration. It focuses on Brazilian futsal players who have left their country of origin to play in Europe. Futsal is an indoor game with 5 players in each team. In some European countries, such as Spain and Portugal, it is a popular form of entertainment that is sufficiently commercialised to sustain full time professional players. Brazilian players are assigned ste- reotypical virtues of skilful styles of play. We interviewed XX players when they returned to Brazil for vacations. The focus of the questions were on three key themes: adaptation to the new country in social and sporting terms, questions of national identity, and some general questions about their attitudes and plans. -

Educació Física I Esportseducació Física I

143 143 1r trimestre (gener-març) 2021 ISSN: 2014-0983 EDUCACIÓ FÍSICA I ESPORTS Publicat: 1 de gener de 2021 EDUCACIÓ FÍSICA I ESPORTS https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2021/1).143.01 NÚMERO 143 1 Nivell de condició física i pràctica EDUCACIÓ FÍSICA I ESPORTS EDUCACIÓ FÍSICA I ESPORTS d’activitat física en escolars 143 adolescents 2021 1 JM 1,2 RA ener-març) José Enrique, Moral-García , Rubén Arroyo-Del Bosque * trimestre (g 1r ISSN: 2014-0983 2 AJ i Alfredo Jiménez-Eguizábal 1 Universidad Pontificia de Salamanca. Facultad de Educación (Espanya) ACTIVITAT FÍSICA I SALUT ACTIVITAT 2 Universidad de Burgos. Facultad de Educación (Espanya) OPEN ACCESS Citació Moral-García, J.E., Arroyo-Del Bosque, R. & Jiménez-Eguizábal, A. (2020). Level of physical condition and practice of physical activity in adolescent schoolchildren. Apunts. Educación Física y Deportes, 143, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2021/1).143.01 Editat per: © Generalitat de Catalunya Resum Departament de la Presidència L’objectiu de l’estudi se centra a conèixer el nivell de condició física dels adolescents Institut Nacional d’Educació i l’associació existent amb la pràctica d’activitat física, gènere i edat. Hi van participar Física de Catalunya (INEFC) 214 estudiants d’ESO, d’entre 13 i 16 anys. Com a instrument per conèixer el nivell ISSN: 2014-0983 d’activitat física setmanal es va emprar l’Adolescent Physical Activity Measure (MVPA) i per a la condició física diferents proves físiques contingudes a la bateria ALPHA- *Correspondència: Rubén Arroyo-Del Bosque Fitness®. -

Different Motor Patterns in Basketball Depending on Gender? Padroes

Cuadernos de Psicología del Deporte, vol. 17, 3, 149-156 © Copyright 2017: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Murcia Recibido: 26/02/2016 Murcia (España) Aceptado: 15/07/2017 ISSN edición impresa: 1578-8423 ISSN edición web (http://revistas.um.es/cpd): 1989-5879 ¿Distintos patrones motrices en baloncesto según género? Diferent motor patterns in basketball depending on gender? Padroes distintos de acordo ao genero no basquete? Pic Aguilar, M. Dpto. de Didácticas Específcas, Universidad de La Laguna Resumen: El objetivo prioritario de la investigación es caracterizar el género After achieving data quality, close to the inter- and intra-observer unit, two mediante el análisis de la conducta motriz en baloncesto. Se seleccionaron analytical techniques were applied: a) detection of behavioral patterns by dos partidos de alta competición en el campeonato del mundo organizado Teme (Magnusson, 2000) and b) Chaid decision trees through SPSS. Te por la FIBA en el año 2014. A través de una metodología observacional y results showed the existence of patterns of play and temporal regularities un diseño nomotético, puntual y multidimensional (Anguera, Blanco-Vi- depending on gender, while by using Chaid multivariate analysis the gen- llaseñor, Hernández-Mendo, & Losada, 2011) fueron registradas conductas der variable was included in the second level of hierarchy of the efective- motrices relacionadas con la circulación del balón y la efcacia de los lanza- ness explanatory variable. From this study, guidelines can be drawn that dores en base a la presencia o ausencia de oposición durante el lanzamiento. help basketball coaches and trainers to build training tasks. Diferences in Para ello, fue diseñado un sistema mixto de registro ‘ad hoc’ formado por 4 behavioral patterns between men and women in basketball were identifed. -

University of Groningen Talent Development from a Complex

University of Groningen Talent Development from a Complex Systems Perspective den Hartigh, Jan Rudolf; Hill, Yannick; van Geert, Paul Published in: Complex Systems in Sport. Linking Theory to Practice DOI: 10.3389/978-2-88945-310-8 IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2017 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): den Hartigh, J. R., Hill, Y., & van Geert, P. (2017). Talent Development from a Complex Systems Perspective. In C. Torrents, P. Passos, & F. Cos (Eds.), Complex Systems in Sport. Linking Theory to Practice (pp. 100-103). Frontiers Media SA. https://doi.org/10.3389/978-2-88945-310-8 Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Mechanism of Social Reproduction of the Culture Futsal: Modelling of The

Advances in Physical Education, 2016, 6, 59-66 Published Online May 2016 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/ape http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ape.2016.62007 Mechanism of Social Reproduction of the Culture Futsal: Modelling of the Universals of Futsal and Sense of the Rules of the Game: Analysis of Shooting at the European Cup Matches Nejah Kacem1, Ayman Guemri2, Chokri Naffeti3, Ali Elloumi1 1State, Culture and Change of Society, Higher Institute of Sport and Education Physics Ksar Saïd, Mannouba, Tunisia 2Group for the Study of Development and Social Environment (GEDES), Faculty of Human and Social Science of Tunis, Tunis, Tunisia 3Educational Department of PAS, Higher Institute of Sport and Education Physics of Sfax, Sfax, Tunisia Received 23 February 2016; accepted 2 May 2016; published 6 May 2016 Copyright © 2016 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract Genre and styles of Futsal playing: a comparison between the European and 2012 World Cups. This paper is the continuation of a research project started in 2012 to identify “genre” and “styles” of playing by national Futsal teams (Manno, 2012). Using a technological approach, the research addresses clinical activity concepts from an educational viewpoint that may be useful for teachers and coaches. With the assistance of a data collection method we compare various phases of the game during the 2012 World Cup with those observed in 2012. This comparison enables us to de- termine a “category” for each game. -

Optimization of Game Formats in U-10 Soccer Using Logistic Regression Analysis

Journal of Human Kinetics volume 54/2016, 163-171 DOI: 10.1515/hukin-2016-0047 163 Section III – Sports Training Optimization of Game Formats in U-10 Soccer Using Logistic Regression Analysis by Mario Amatria1, Daniel Lapresa2, Javier Arana3, M. Teresa Anguera4, Belén Garzón2 Small-sided games provide young soccer players with better opportunities to develop their skills and progress as individual and team players. There is, however, little evidence on the effectiveness of different game formats in different age groups, and furthermore, these formats can vary between and even within countries. The Royal Spanish Soccer Association replaced the traditional grassroots 7-a-side format (F-7) with the 8-a-side format (F-8) in the 2011- 12 season and the country’s regional federations gradually followed suit. The aim of this observational methodology study was to investigate which of these formats best suited the learning needs of U-10 players transitioning from 5-a- side futsal. We built a multiple logistic regression model to predict the success of offensive moves depending on the game format and the area of the pitch in which the move was initiated. Success was defined as a shot at the goal. We also built two simple logistic regression models to evaluate how the game format influenced the acquisition of technical- tactical skills. It was found that the probability of a shot at the goal was higher in F-7 than in F-8 for moves initiated in the Creation Sector-Own Half (0.08 vs 0.07) and the Creation Sector-Opponent's Half (0.18 vs 0.16). -

2019 Futsal Under-19 EURO Programme

8-14 September Official programme 1 CONTENTS SATURS The official channel for European football From the UEFA Champions League, UEFA Women’s Champions League, 22 Interview: Lucas Moura 8 20 UEFA Europa League, UEFA Nations League and UEFA EURO 2020, to youth football Intervija: Lukass Moura and futsal, UEFA.com has the European game covered. Group B / B Grupa 26 Croatia Horvātija 28 Ukraine Ukraina 30 Spain Spānija 32 The Netherlands 5 UEFA President’s message Nīderlande UEFA prezidenta uzruna 34 ‘A unique opportunity’ 7 Latvian FA President’s message “Unikāla iespēja” Latvijas Futbola federācijas 38 Road to Riga prezidenta uzruna Ceļš uz Rīgu 8 Futsal’s new dawn Jaunā telpu futbola ēra 22 Group A / A Grupa 12 Latvia Latvija 14 Poland Polija 16 Portugal Portugāle 18 Russia Krievija 20 Match schedule Spēļu grafiks UEFA publications manager / UEFA publikācijas menedžeris Production / Producenti Emmanuel Deconche Tessanna Macleod, Kat Rickards Editor / Redaktors Translation / Tulkošana Michael Harrold Libero Language Lab Ltd Design / Dizains Photography / Fotogrāfijas Darlene Cossentino Getty, UEFA, LFF, PZPN, FPF, RFS, HNS, UAF, RFEF, KNVB Art director / Mākslinieciskais direktors Oliver Meikle Designed and produced by TwelfthMan on behalf of UEFA Contributors / Autori Chris Burke, Mark Chaplin, Andrew Haslam, Anthony ©UEFA 2019. All rights reserved. The UEFA word, the UEFA Naughton, Sean O’Flaherty, Mihail Korolev, Piotr logo and all marks related to UEFA and competitions are Koźmiński, Luis Piedade, Dmitri Rogovitski, Elvir Islamović, protected by trade marks and/or copyright of UEFA. No use Bogdan Buga, Dani Huerta, Derek Brookman for commercial purposes may be made of such trade marks. -

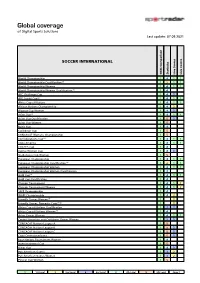

Sportradar Coverage List

Global coverage of Digital Sports Solutions Last update: 07.09.2021 SOCCER INTERNATIONAL Odds Comparison Statistics Live Scores Live Centre World Championship 1 4 1 1 World Championship Qualification (1) 1 2 1 1 World Championship Women 1 4 1 1 World Championship Women Qualification (1) 1 4 AFC Challenge Cup 1 4 3 AFF Suzuki Cup (6) 1 4 1 1 Africa Cup of Nations 1 4 1 1 African Nations Championship 1 4 2 Algarve Cup Women 1 4 3 Asian Cup (6) 1 4 1 1 Asian Cup Qualification 1 5 3 Asian Cup Women 1 5 Baltic Cup 1 4 Caribbean Cup 1 5 CONCACAF Womens Championship 1 5 Confederations Cup (1) 1 4 1 1 Copa America 1 4 1 1 COSAFA Cup 1 4 Cyprus Women Cup 1 4 3 SheBelieves Cup Women 1 5 European Championship 1 4 1 1 European Championship Qualification (1) 1 2 1 1 European Championship Women 1 4 1 1 European Championship Women Qualification 1 4 Gold Cup (6) 1 4 1 1 Gold Cup Qualification 1 4 Olympic Tournament 1 4 1 2 Olympic Tournament Women 1 4 1 2 SAFF Championship 1 4 WAFF Championship 1 4 2 Friendly Games Women (1) 1 2 Friendly Games, Domestic Cups (1) (2) 1 2 Africa Cup of Nations Qualification 1 3 3 Africa Cup of Nations Women (1) 1 4 Asian Games Women 1 4 1 1 Central American and Caribbean Games Women 1 3 3 CONCACAF Nations League A 1 5 CONCACAF Nations League B 1 5 3 CONCACAF Nations League C 1 5 3 Copa Centroamericana 1 5 3 Four Nations Tournament Women 1 4 Intercontinental Cup 1 5 Kings Cup 1 4 3 Pan American Games 1 3 2 Pan American Games Women 1 3 2 Pinatar Cup Women 1 5 1 1st Level 2 2nd Level 3 3rd Level 4 4th Level 5 5th Level Page: -

Invitation to Express Interest

PRODUCTION OF BRANDED MATERIALS Invitation to express interest INVITATION TO EXPRESS INTEREST 1. Introduction UEFA wishes to select one or several company(ies) for the production of branded materials for different UEFA competition cycles and their respective seasons as listed below, each of which are organised and administrated by UEFA, the governing body of European football: • UEFA Champions League™ o UEFA Champions League™ Seasons 2021–24 (as of play-off round) (UCL) o UEFA Champions League™ Finals 2022/2023/2024 (UCLF) • UEFA Europa League™ o UEFA Europa League™ Seasons 2021–24 (as of group stage) (UEL) o UEFA Europa League™ Finals 2022/2023/2024 (UELF) • UEFA Europa Conference League™ o UEFA Europa Conference League™ Seasons 2021–24 (as of group stage) (UECL) o UEFA Europa Conference League™ Finals 2022/2023/2024 (UECLF) • UEFA Women’s Champions League™ o UEFA Women’s Champions League™ Seasons 2021-25 (as of group stage) (UWCL) o UEFA Women’s Champions League™ Finals 2022/2023/2024/2025 (UWCLF) • UEFA Super Cup™ 2021/2022/2023 • UEFA Youth League™ Finals 2022/2023/2024 (UYLF) • European Club Football Season Kick-off 2021/2022/2023 (ECF) • Friendly Matches 2022-2023 (FM) • European Qualifiers™ 2022-2023 (EQ) • UEFA Nations League™ o UEFA Nations League™ 2022-2023 (UNL) o UEFA Nations League™ Finals 2021/2023 (UNLF) • UEFA Under-17 Championship™ 2022/2023/2024/2025 (U17) • UEFA Under-19 Championship™ 2022/2023/2024/2025 (U19) • UEFA Under-21 Championship™ 2022/2023/2024/2025 (U21) • UEFA Women’s Under-17 Championship™ 2022/2023/2024/2025 (WU17) • UEFA Women’s Under-1 9 Championship™ 2022/2023/2024/2025 (WU19) • UEFA Futsal Championship™ 2022 (Futsal EURO) • UEFA Futsal Champions League™ 2022/2023/2024/2025 (UFCL) • UEFA European Women’s Futsal Championship™ 2023/2025 (Futsal Women’s EURO) • UEFA European Under-19 Futsal Championship™ 2023/2025 (Futsal U19) • UEFA Regions’ Cup™ 2023/2025 (Regions’ Cup) • Other competitions on request.