Divestment and Stranded Assets in the Low-Carbon Transition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cost of Capital: an International Comparison

The Cost of Capital: An International Comparison The Cost of Capital: An International Comparison EXECUTIVE SUMMARY June 2006 June 2006 The Cost of Capital: An International Comparison EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Oxera Consulting Ltd Park Central 40/41 Park End Street Oxford OX1 1JD Telephone: +44(0) 1865 253 000 Fax: +44(0) 1865 251 172 www.oxera.com London Stock Exchange and the coat of arms device are registered trade marks plc June 2006 The Cost of Capital: An International Comparison is published by the City of London. The authors of this report are Leonie Bell, Luis Correia da Silva and Agris Preimanis of Oxera Consulting Ltd. This report is intended as a basis for discussion only. Whilst every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy and completeness of the material in this report, the authors, Oxera Consulting Ltd, the London Stock Exchange, and the City of London, give no warranty in that regard and accept no liability for any loss or damage incurred through the use of, or reliance upon, this report or the information contained herein. June 2006 © City of London PO Box 270, Guildhall London EC2P 2EJ www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/economicresearch Table of Contents Forewords ………………………………………………………………………………... 1 Executive Summary …………………………………………………………………….. 3 1. Introduction ………………………………………………………………………… 7 2. Overview of public equity and corporate debt markets in London and other financial centres …………………………………………………………………… 9 2.1 Equity markets ………………………………………………………………… 9 2.2 Corporate debt markets ………………………………………………………... 10 3. The cost of raising equity in London and other equity markets ……………… 12 3.1 Framework of analysis ……………………………………………………………….. 12 3.2 IPO costs in different markets ……………………………………………………… 17 3.3 Trading costs in the secondary market ……………………………………………. -

Divestment May Burst the Carbon Bubble If Investors' Beliefs Tip To

Divestment may burst the carbon bubble if investors’ beliefs tip to anticipating strong future climate policy Birte Ewers,1;2;∗ Jonathan F. Donges,1;3;∗;# Jobst Heitzig1, Sonja Peterson4 1Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, Member of the Leibniz Association, P.O. Box 60 12 03, 14412 Potsdam, Germany 2Department of Economics, University of Kiel, Olshausenstraße 40, 24098 Kiel, Germany 3Stockholm Resilience Centre, Stockholm University, Kraftriket¨ 2B, 114 19 Stockholm, Sweden 4Kiel Institute for the World Economy, Kiellinie 66, 24105 Kiel, Germany ∗The first two authors share the lead authorship. #To whom correspondence should be addressed; E-mail: [email protected] February 21, 2019 To achieve the ambitious aims of the Paris climate agreement, the majority of fossil-fuel reserves needs to remain underground. As current national govern- ment commitments to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions are insufficient by far, actors such as institutional and private investors and the social movement on divestment from fossil fuels could play an important role in putting pressure on national governments on the road to decarbonization. Using a stochastic arXiv:1902.07481v1 [q-fin.GN] 20 Feb 2019 agent-based model of co-evolving financial market and investors’ beliefs about future climate policy on an adaptive social network, here we find that the dy- namics of divestment from fossil fuels shows potential for social tipping away from a fossil-fuel based economy. Our results further suggest that socially responsible investors have leverage: a small share of 10–20 % of such moral investors is sufficient to initiate the burst of the carbon bubble, consistent with 1 the Pareto Principle. -

Initial Public Offerings

November 2017 Initial Public Offerings An Issuer’s Guide (US Edition) Contents INTRODUCTION 1 What Are the Potential Benefits of Conducting an IPO? 1 What Are the Potential Costs and Other Potential Downsides of Conducting an IPO? 1 Is Your Company Ready for an IPO? 2 GETTING READY 3 Are Changes Needed in the Company’s Capital Structure or Relationships with Its Key Stockholders or Other Related Parties? 3 What Is the Right Corporate Governance Structure for the Company Post-IPO? 5 Are the Company’s Existing Financial Statements Suitable? 6 Are the Company’s Pre-IPO Equity Awards Problematic? 6 How Should Investor Relations Be Handled? 7 Which Securities Exchange to List On? 8 OFFER STRUCTURE 9 Offer Size 9 Primary vs. Secondary Shares 9 Allocation—Institutional vs. Retail 9 KEY DOCUMENTS 11 Registration Statement 11 Form 8-A – Exchange Act Registration Statement 19 Underwriting Agreement 20 Lock-Up Agreements 21 Legal Opinions and Negative Assurance Letters 22 Comfort Letters 22 Engagement Letter with the Underwriters 23 KEY PARTIES 24 Issuer 24 Selling Stockholders 24 Management of the Issuer 24 Auditors 24 Underwriters 24 Legal Advisers 25 Other Parties 25 i Initial Public Offerings THE IPO PROCESS 26 Organizational or “Kick-Off” Meeting 26 The Due Diligence Review 26 Drafting Responsibility and Drafting Sessions 27 Filing with the SEC, FINRA, a Securities Exchange and the State Securities Commissions 27 SEC Review 29 Book-Building and Roadshow 30 Price Determination 30 Allocation and Settlement or Closing 31 Publicity Considerations -

Ben Spies-Butcher & Frank Stilwell

CLIMATE CHANGE POLICY AND ECONOMIC RECESSION Ben Spies Butcher and Frank Stilwell The economic difficulties following from the global financial crisis raise important and challenging questions about the strategies necessary to deal with the problem of climate change. Does the recession undermine the case for an emissions trading system? If so, what could be done instead to reduce environmentally hazardous emissions? Can the problems of recession and climate change be simultaneously redressed? First, it is pertinent to point to a paradox – that the recession is good for the environment. Indeed, over the past year the failures of global capitalism have achieved goals that even optimistic environmentalists previously thought unreachable. The close correlation between economic growth and carbon emissions has meant that, as production has fallen, so too have emissions. However, the short term gains have come at significant cost, and there is little reason to expect that these gains are sustainable. The Stern Report in the UK acknowledged a strong correlation between economic growth and increased carbon emissions (Stern 2007, xi). There is approximately a 0.9 per cent increase in emissions for every 1 per cent increase in growth (Adam 2009). The recession reverses this logic. Indeed, economic contraction has been particularly pronounced in emissions intensive industries, with industrial production in the United States down by almost 13 percent in the year to March 2009, and with declines concentrated in manufacturing and construction (US Federal Reserve 2009). In Japan exports fell over 40 per cent in the year to April 2009 (Ministry of Finance 2009). Globally, 2009 may be the first year in which global carbon emissions actually decline. -

Uva-F-1274 Methods of Valuation for Mergers And

Graduate School of Business Administration UVA-F-1274 University of Virginia METHODS OF VALUATION FOR MERGERS AND ACQUISITIONS This note addresses the methods used to value companies in a merger and acquisitions (M&A) setting. It provides a detailed description of the discounted cash flow (DCF) approach and reviews other methods of valuation, such as book value, liquidation value, replacement cost, market value, trading multiples of peer firms, and comparable transaction multiples. Discounted Cash Flow Method Overview The discounted cash flow approach in an M&A setting attempts to determine the value of the company (or ‘enterprise’) by computing the present value of cash flows over the life of the company.1 Since a corporation is assumed to have infinite life, the analysis is broken into two parts: a forecast period and a terminal value. In the forecast period, explicit forecasts of free cash flow must be developed that incorporate the economic benefits and costs of the transaction. Ideally, the forecast period should equate with the interval in which the firm enjoys a competitive advantage (i.e., the circumstances where expected returns exceed required returns.) For most circumstances a forecast period of five or ten years is used. The value of the company derived from free cash flows arising after the forecast period is captured by a terminal value. Terminal value is estimated in the last year of the forecast period and capitalizes the present value of all future cash flows beyond the forecast period. The terminal region cash flows are projected under a steady state assumption that the firm enjoys no opportunities for abnormal growth or that expected returns equal required returns in this interval. -

Stock in a Closely Held Corporation:Is It a Security for Uniform Commercial Code Purposes?

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 42 Issue 2 Issue 2 - March 1989 Article 6 3-1989 Stock in a Closely Held Corporation:Is It a Security for Uniform Commercial Code Purposes? Tracy A. Powell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Securities Law Commons Recommended Citation Tracy A. Powell, Stock in a Closely Held Corporation:Is It a Security for Uniform Commercial Code Purposes?, 42 Vanderbilt Law Review 579 (1989) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol42/iss2/6 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Stock in a Closely Held Corporation: Is It a Security for Uniform Commercial Code Purposes? I. INTRODUCTION ........................................ 579 II. JUDICIAL DECISIONS ................................... 582 A. The Blasingame Decision ......................... 582 B. Article 8 Generally .............................. 584 C. Cases Deciding Close Stock is Not a Security ...... 586 D. Cases Deciding Close Stock is a Security .......... 590 E. Problem Areas Created by a Decision that Close Stock is Not a Security .......................... 595 III. STATUTORY ANALYSIS .................................. 598 A. Statutory History ................................ 598 B. Official Comments to the U.C.C. .................. 599 1. In G eneral .................................. 599 2. Official Comments to Article 8 ................ 601 3. Interpreting the U.C.C. as a Whole ........... 603 IV. CONCLUSION .......................................... 605 I. INTRODUCTION The term security has many applications. No application, however, is more important than when an interest owned or traded is determined to be within the legal definition of security. -

IPO Or Divestiture: Making Informed Decisions

IPO or divestiture: Making informed decisions By Yael Woodward Amaral, Partner, Accounting Advisory, KPMG in Canada To divest or go public. It is a simple proposition with complex considerations. No doubt, pursuing an initial public offering (IPO) is a viable option for private equity (PE) funds looking to raise cash from a portfolio asset they are not ready to part ways with, but like any major portfolio decision, it pays to go in with eyes wide open. Taking the IPO journey has its merits. Current market “ Going public is not a panacea for conditions are making it more difficult for funds to operate on a debt leverage model approach at the same levels of return. difficult times. As anyone who has As such, going public may be a mechanism to extract capital ventured down the IPO path can from the asset while maintaining ownership. attest, it only means trading one set of challenges for another.” The true cost of going public Even still, going public is not a panacea for difficult times. Economy of scale As anyone who has ventured down the IPO path can attest, It is one thing to say your organization wants to be public it only means trading one set of challenges for another. and another to be ready for the costs, compliance, and Whether raising a million dollars or a billion, going public public scrutiny that entails. The massive shift in the reporting means becoming beholden to new rules, processes, public environment alone can be a significant challenge for the shareholders and regulators. This can be unfamiliar territory under-prepared, as it demands significant financial reporting for funds that are used to working in a more autonomous capabilities, controls, IT infrastructure, human resource environment and selling acquisitions when the numbers deem considerations and governance that simply cannot be it best. -

11. Conflicts of Interest

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST Anti-Bribery Guidance Chapter 11 Transparency International (TI) is the world’s leading non-governmental anti-corruption organisation. With more than 100 chapters worldwide, TI has extensive global expertise and understanding of corruption. Transparency International UK (TI-UK) is the UK chapter of TI. We raise awareness about corruption; advocate legal and regulatory reform at national and international levels; design practical tools for institutions, individuals and companies wishing to combat corruption; and act as a leading centre of anti-corruption expertise in the UK. Acknowledgements: We would like to thank DLA Piper, FTI Consulting and the members of the Expert Advisory Committee for advising on the development of the guidance: Andrew Daniels, Anny Tubbs, Fiona Thompson, Harriet Campbell, Julian Glass, Joshua Domb, Sam Millar, Simon Airey, Warwick English and Will White. Special thanks to Jean-Pierre Mean and Moira Andrews. Editorial: Editor: Peter van Veen Editorial staff: Alice Shone, Rory Donaldson Content author: Peter Wilkinson Project manager: Rory Donaldson Publisher: Transparency International UK Design: 89up, Jonathan Le Marquand, Dominic Kavakeb Launched: October 2017 © 2018 Transparency International UK. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in parts is permitted providing that full credit is given to Transparency International UK and that any such reproduction, in whole or in parts, is not sold or incorporated in works that are sold. Written permission must be sought from Transparency International UK if any such reproduction would adapt or modify the original content. If any content is used then please credit Transparency International UK. Legal Disclaimer: Every effort has been made to verify the accuracy of the information contained in this report. -

Business Ethics: a Panacea for Reducing Corruption and Enhancing National Development

Nigerian Journal of Business Education (NIGJBED) Volume 5 No.2, 2018 BUSINESS ETHICS: A PANACEA FOR REDUCING CORRUPTION AND ENHANCING NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT AKPANOBONG, UYAI EMMANUEL, Ph.D. Department of Vocational Education, Faculty of Education, University of Uyo Email:[email protected] Abstract In recent times there are scandals of unethical behaviours, corrupt practices, lack of accountability and transparency amongst public officials, political office holders, business managers and employees in the country. Therefore, there is an urgent need for public sector institutions to strengthen the ethics of their profession, integrity, honesty, transparency, confidentiality, and accountability in the public service. The paper further attempt to discuss the need for business ethics and some practices and behaviours which undermined the ethical behaviours of public official with strong emphasis on corruptions causes and preventions, conflicts of interest, consequences of unethical behaviour and resources management. The paper also outlined some measures on how to combat the evil called corruption in public service and business organizations. It is concluded that if all measures are taken into consideration the National Development may be achieved. Keywords: Ethics, unethical, transparency, accountability, corruption. Introduction In every business organization, there must be a laid down rules, values norms, order and other guiding principles which may be in form of ethics. The essence of this is to guide both the employer and the employees in achieving the organizational goals and at the same time help in checks and balances. Luanne (2017 saw ethics as the principles and values an individual uses to govern his activities and decisions. Therefore, Business Ethics could be described as that aspect of corporate governance that has to do with the moral values of managers encouraging them to be transparent in business dealing (Chienweike, 2010). -

Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG)

Exhibit 21 Initiative arbon Tracker Carbon supply cost curves: Evaluating financial risk to gas capital expenditures About Carbon Tracker Acknowledgements Disclaimer The Carbon Tracker Initiative (CTI) is a financial Authored by James Leaton, Andrew Grant, Matt Carbon Tracker is a non-profit company set-up not for profit financial think-tank. Its goal is to Gray, Luke Sussams, with communications advice to produce new thinking on climate risk. The align the capital markets with the risks of climate from Stefano Ambrogi and Margherita Gagliardi organisation is funded by a range of European and change. Since its inception in 2009 Carbon Tracker at Carbon Tracker. This paper is a summary which American foundations. Carbon Tracker is not an has played a pioneering role in popularising the draws on research conducted in partnership with investment adviser, and makes no representation concepts of the carbon bubble, unburnable carbon Energy Transition Advisors, ETA, led by Mark Fulton, regarding the advisability of investing in any and stranded assets. These concepts have entered with Paul Spedding. particular company or investment fund or other the financial lexicon and are being taken increasingly vehicle. A decision to invest in any such investment The underlying analysis in this report prepared seriously by a range of financial institutions including fund or other entity should not be made in by Carbon Tracker and ETA is based on supply investment banks, ratings agencies, pension funds reliance on any of the statements set forth in this cost data licensed from Wood Mackenzie Limited. and asset managers. publication. While the organisations have obtained Wood Mackenzie is a global leader in commercial information believed to be reliable, they shall not intelligence for the energy, metals and mining Contact be liable for any claims or losses of any nature industries. -

2020: the Climate Turning Point, Either in Whole Or in Part, from the Identification of Six Milestones to Guidance on Analysis of the Milestone Targets

analysis by: CLIMATE ACTION TRACKER reviews by: 1 Acknowledgements Preface authors Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research: Stefan Rahmstorf and Anders Levermann Report writers Independent Policy Analyst and Writer: Chloe Revill and Victoria Harris Analytical contributors Carbon Tracker: James Leaton Climate Action Tracker: Michiel Schaeffer, Andrzej Ancygier, Bill Hare, Niklas Roaming , Paola Parra, Delphine Deryng, Mahlet Melkie, and Claire Fyson (Climate Analytics); Niklas Höhne, Sebastian Sterl, and Hanna Fekete (New Climate Institute); Yvonne Deng, Kornelis Blok, and Carsten Petersdorff (Ecofys, a Navigant company) Yale University: Angel Hsu, Amy Weinfurter, and Carlin Rosengarten Special thank you to the additional organizations and individuals who provided input or reviewed the analysis for 2020: The Climate Turning Point, either in whole or in part, from the identification of six milestones to guidance on analysis of the milestone targets. Organizations and individuals: Climate Policy Initiative (CPI), Conservation International (CI) with a special thank you to Shyla Raghav; International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), The New Climate Economy (NCE), Partnership on Sustainable Low Carbon Transport (SLoCaT), Reid Detchon at the UN Foundation, SYSTEMIQ, We Mean Business (WMB), and World Resources Institute (WRI) 2 OUR SHARED MISSION FOR 2020 PREFACE: WHY GLOBAL EMISSIONS MUST PEAK BY 2020 Authored by Stefan Rahmstorf and Anders Levermann Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research In the landmark Paris Climate Agreement, the world’s nations have committed to “holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels”. This goal is deemed necessary to avoid incalculable risks to humanity, and it is feasible – but realistically only if global emissions peak by the year 2020 at the latest. -

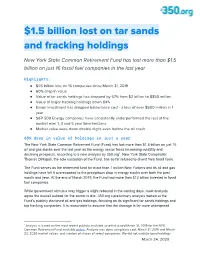

$1.5 Billion Lost on Tar Sands and Fracking Holdings

$1.5 billion lost on tar sands and fracking holdings New York State Common Retirement Fund has lost more than $1.5 billion on just 16 fossil fuel companies in the last year Highlights: ● $1.5 billion loss on 16 companies since March 31, 2019 ● 60% drop in value ● Value of tar sands holdings has dropped by 57% from $2 billion to $850 million ● Value of major fracking holdings down 84% ● Exxon investment has dropped below base cost - a loss of over $500 million in 1 year ● S&P 500 Energy companies have consistently underperformed the rest of the market over 1, 3 and 5 year time horizons ● Market value were down double digits even before the oil crash 60% drop in value of holdings in just a year The New York State Common Retirement Fund (Fund) has lost more than $1.5 billion on just 16 oil and gas stocks over the last year as the energy sector faces increasing volatility and declining prospects, according to a new analysis by 350.org1. New York State Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli, the sole custodian of the Fund, has so far refused to divest from fossil fuels. The Fund serves as the retirement fund for more than 1 million New Yorkers and its oil and gas holdings have left it overexposed to the precipitous drop in energy stocks over both the past month and year. At the end of March 2019, the Fund had more than $13 billion invested in fossil fuel companies. While government stimulus may trigger a slight rebound in the coming days, most analysts agree the overall outlook for the sector is dim.