The Grove. Working Papers on English Studies 27 (2020): 123-134

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Devon Allman, Son of Gregg Allman of the Allman Brothers Band, Leads His Band Called Honey Tribe and He Is a Member of Royal Southern Brotherhood As Well

Singer/guitarist Devon Allman, son of Gregg Allman of the Allman Brothers Band, leads his band called Honey Tribe and he is a member of Royal Southern Brotherhood as well. Now Devon has recorded his first solo album that is made up songs that are written about his personal life along with one Tom Petty cover song. The 2013 International Blues Challenge was held in Memphis from January 29 – February 2. Ghost Town Blues Band from Memphis did not win, but they did make it to the top ten. They have released two excellent albums and can be seen performing at many local venues. Former Memphian Little G. Weevil won the solo/duo category and best guitarist in that category at the IBC. His excellent album The Teaser is a great example of why he won. Boz Scaggs came to Memphis to record his new album titled, surprisingly enough, Memphis. Most surprising is how well he handles the soul and blues songs on Memphis. Devon Allman – Turquoise Devon Allman is Gregg Allman’s son, but he grew up with his mom in Corpus Christi, Texas, away from the rock & roll lifestyle. He didn’t even meet his dad until he was a teenager, but they are now very close. While Devon was influenced by The Allman Brothers, he was also influenced by a myriad of other musicians and styles of music, so he really doesn’t sound much like The Allman Brothers. Devon has his own unique sound, both in his guitar playing and his singing. Some have tried to compare him to his uncle Duane, but aside from both having blonde hair and favoring Les Paul guitars, there aren’t a lot of similarities. -

Steve Cropper | Primary Wave Music

STEVE CROPPER facebook.com/stevecropper twitter.com/officialcropper Image not found or type unknown youtube.com/channel/UCQk6gXkhbUNnhgXHaARGskg playitsteve.com en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steve_Cropper open.spotify.com/artist/1gLCO8HDtmhp1eWmGcPl8S If Yankee Stadium is “the house that Babe Ruth built,” Stax Records is “the house that Booker T, and the MG’s built.” Integral to that potent combination is MG rhythm guitarist extraordinaire Steve Cropper. As a guitarist, A & R man, engineer, producer, songwriting partner of Otis Redding, Eddie Floyd and a dozen others and founding member of both Booker T. and the MG’s and The Mar-Keys, Cropper was literally involved in virtually every record issued by Stax from the fall of 1961 through year end 1970.Such credits assure Cropper of an honored place in the soul music hall of fame. As co-writer of (Sittin’ On) The Dock Of The Bay, Knock On Wood and In The Midnight Hour, Cropper is in line for immortality. Born on October 21, 1941 on a farm near Dora, Missouri, Steve Cropper moved with his family to Memphis at the age of nine. In Missouri he had been exposed to a wealth of country music and little else. In his adopted home, his thirsty ears amply drank of the fountain of Gospel, R & B and nascent Rock and Roll that thundered over the airwaves of both black and white Memphis radio. Bit by the music bug, Cropper acquired his first mail order guitar at the age of 14. Personal guitar heroes included Tal Farlow, Chuck Berry, Jimmy Reed, Chet Atkins, Lowman Pauling of the Five Royales and Billy Butler of the Bill Doggett band. -

Farm Aid: a Case Study of a Charity Rock Organization Andrew Palen University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations December 2016 Farm Aid: a Case Study of a Charity Rock Organization Andrew Palen University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons, and the Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons Recommended Citation Palen, Andrew, "Farm Aid: a Case Study of a Charity Rock Organization" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1399. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1399 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FARM AID: A CASE STUDY OF A CHARITY ROCK ORGANIZATION by Andrew M. Palen A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Media Studies at The University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee December 2016 ABSTRACT FARM AID: A CASE STUDY ON THE IMPACT OF A CHARITY ROCK ORGANIZATION by Andrew M. Palen The University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee, 2016 Under the Supervision of Professor David Pritchard This study examines the impact that the non-profit organization Farm Aid has had on the farming industry, policy, and the concert realm known as charity rock. This study also examines how the organization has maintained its longevity. By conducting an evaluation on Farm Aid and its history, the organization’s messaging and means to communicate, a detailed analysis of the past media coverage on Farm Aid from 1985-2010, and a phone interview with Executive Director Carolyn Mugar, I have determined that Farm Aid’s impact is complex and not clear. -

A Portraiture Study of Three Successful Indigenous Educators and Community Leaders Who Experience Personal Renewal in Their Practice of Cultural Restoration Kathrin W

Lesley University DigitalCommons@Lesley Educational Studies Dissertations Graduate School of Education (GSOE) Spring 8-25-2017 Full Circle: A Portraiture Study of Three Successful Indigenous Educators and Community Leaders Who Experience Personal Renewal In their Practice of Cultural Restoration Kathrin W. McCarthy Lesley University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/education_dissertations Part of the Adult and Continuing Education and Teaching Commons, Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Research Commons, and the Indigenous Education Commons Recommended Citation McCarthy, Kathrin W., "Full Circle: A Portraiture Study of Three Successful Indigenous Educators and Community Leaders Who Experience Personal Renewal In their Practice of Cultural Restoration" (2017). Educational Studies Dissertations. 125. https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/education_dissertations/125 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School of Education (GSOE) at DigitalCommons@Lesley. It has been accepted for inclusion in Educational Studies Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Lesley. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running Head: PORTRAITS OF THREE SUCCESSFUL ALASKA NATIVE EDUCATORS Full Circle: A Portraiture Study of Three Successful Indigenous Educators and Community Leaders Who Experience Personal Renewal In their Practice of Cultural Restoration By Kathrin W. McCarthy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Educational Studies Lesley University August 2017 PORTRAITS OF THREE SUCCESSFUL ALASKA NATIVE EDUCATORS ii PORTRAITS OF THREE SUCCESSFUL ALASKA NATIVE EDUCATORS iii Abstract This qualitative inquiry uses the narrative methodology of portraiture to explore how the experiences of three successful Native educators and community leaders can contribute to the adult learning and development literature. -

Strange Brew√ Fresh Insights on Rock Music | Edition 03 of September 30 2006

M i c h a e l W a d d a c o r ‘ s πStrange Brew Fresh insights on rock music | Edition 03 of September 30 2006 L o n g m a y y o u r u n ! A tribute to Neil Young: still burnin‘ at 60 œ part two Forty years ago, in 1966, Neil Young made his Living with War (2006) recording debut as a 20-year-old member of the seminal, West Coast folk-rock band, Buffalo Springfield, with the release of this band’s A damningly fine protest eponymous first album. After more than 35 solo album with good melodies studio albums, The Godfather of Grunge is still on fire, raging against the System, the neocons, Rating: ÆÆÆÆ war, corruption, propaganda, censorship and the demise of human decency. Produced by Neil Young and Niko Bolas (The Volume Dealers) with co-producer L A Johnson. In this second part of an in-depth tribute to the Featured musicians: Neil Young (vocals, guitar, Canadian-born singer-songwriter, Michael harmonica and piano), Rick Bosas (bass guitar), Waddacor reviews Neil Young’s new album, Chad Cromwell (drums) and Tommy Bray explores his guitar playing, re-evaluates the (trumpet) with a choir led by Darrell Brown. overlooked classic album from 1974, On the Beach, and briefly revisits the 1990 grunge Songs: After the Garden / Living with War / The classic, Ragged Glory. This edition also lists the Restless Consumer / Shock and Awe / Families / Neil Young discography, rates his top albums Flags of Freedom / Let’s Impeach the President / and highlights a few pieces of trivia about the Lookin’ for a Leader / Roger and Out / America artist, his associates and his interests. -

The Opinion Fuller Seminary Publications

Fuller Theological Seminary Digital Commons @ Fuller The Opinion Fuller Seminary Publications 1-1-1968 The Opinion - Vol. 07, No. 04 Fuller Theological Seminary Thomas F. Johnson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fuller.edu/fts-opinion Recommended Citation Fuller Theological Seminary and Johnson, Thomas F., "The Opinion - Vol. 07, No. 04" (1968). The Opinion. 111. https://digitalcommons.fuller.edu/fts-opinion/111 This Periodical is brought to you for free and open access by the Fuller Seminary Publications at Digital Commons @ Fuller. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Opinion by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Fuller. For more information, please contact [email protected]. the opinion JANUARY, 1968 Vol. VII, No. 4 CONTENTS Editorial Page 2 In Pursuit of Justice 3 Jaymes Morgan, Jr War and Peace 5 Ron Crandal1 Hawks, Doves and Ostriches 8 Thomas F. Johnson Home from Vietnam: June 14, 1967 10 M. Edward Clark Thou Shalt not Something or Other 14 Art Hoppe A Prayer 15 Mark Twain Letter From Vietnam 16 Letters to the Editor 19 the opinion is piiblished the first Thursday of each month throughout the school year by students at Fuller Theological Seminary, 135 R. Oakland Ave., Pasadena, Cal. the opinion welcomes a variety of opinions consistent with general academic standards. Therefore, opinions expressed in articles and letters are those of the auth ors and are not to be construed as the view of the sem inary, faculty, student council, or editors of the opinion. Editor in chief........ .....Thomas F. Johnson Managing Editor ..... ........ Thomas S. Johnson Literary Editor............ -

2015 Year in Review

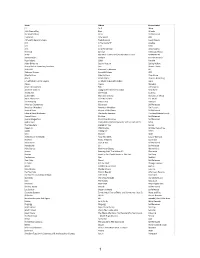

Ar#st Album Record Label !!! As If Warp 11th Dream Day Beet Atlan5c The 4onthefloor All In Self-Released 7 Seconds New Wind BYO A Place To Bury StranGers Transfixia5on Dead Oceans A.F.I. A Fire Inside EP Adeline A.F.I. A.F.I. Nitro A.F.I. Sing The Sorrow Dreamworks The Acid Liminal Infec5ous Music ACTN My Flesh is Weakness/So God Damn Cold Self-Released Tarmac Adam In Place Onesize Records Ryan Adams 1989 Pax AM Adler & Hearne Second Nature SprinG Hollow Aesop Rock & Homeboy Sandman Lice Stones Throw AL 35510 Presence In Absence BC Alabama Shakes Sound & Colour ATO Alberta Cross Alberta Cross Dine Alone Alex G Beach Music Domino Recording Jim Alfredson's Dirty FinGers A Tribute to Big John Pa^on Big O Algiers Algiers Matador Alison Wonderland Run Astralwerks All Them Witches DyinG Surfer Meets His Maker New West All We Are Self Titled Domino Jackie Allen My Favorite Color Hans Strum Music AM & Shawn Lee Celes5al Electric ESL Music The AmazinG Picture You Par5san American Scarecrows Yesteryear Self Released American Wrestlers American Wrestlers Fat Possum Ancient River Keeper of the Dawn Self-Released Edward David Anderson The Loxley Sessions The Roayl Potato Family Animal Hours Do Over Self-Released Animal Magne5sm Black River Rainbow Self Released Aphex Twin Computer Controlled Acous5c Instruments Part 2 Warp The Aquadolls Stoked On You BurGer Aqueduct Wild KniGhts Wichita RecordinGs Aquilo CallinG Me B3SCI Arca Mutant Mute Architecture In Helsinki Now And 4EVA Casual Workout The Arcs Yours, Dreamily Nonesuch Arise Roots Love & War Self-Released Astrobeard S/T Self-Relesed Atlas Genius Inanimate Objects Warner Bros. -

Death, Travel and Pocahontas the Imagery on Neil Young's Album

Hugvísindasvið Death, Travel and Pocahontas The imagery on Neil Young’s album Rust Never Sleeps Ritgerð til B.A.-prófs Hans Orri Kristjánsson September 2008 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Enskuskor Death, Travel and Pocahontas The imagery on Neil Young’s album Rust Never Sleeps Ritgerð til B.A.-prófs Hans Orri Kristjánsson Kt.: 260180-2909 Leiðbeinandi: Sveinn Yngvi Egilsson September 2008 Abstract The following essay, “Death, Travel and Pocahontas,” seeks to interpret the imagery on Neil Young’s album Rust Never Sleeps. The album was released in July 1979 and with it Young was venturing into a dialogue of folk music and rock music. On side one of the album the sound is acoustic and simple, reminiscent of the folk genre whereas on side two Young is accompanied by his band, The Crazy Horse, and the sound is electric, reminiscent of the rock genre. By doing this, Young is establishing the music and questions of genre and the interconnectivity between folk music and rock music as one of the theme’s of the album. Young explores these ideas even further in the imagery of the lyrics on the album by using popular culture icons. The title of the album alone symbolizes the idea of both death and mortality, declaring that originality is transitory. Furthermore he uses recurring images, such as death, to portray his criticism on the music business and lack of originality in contemporary musicians. Ideas of artistic freedom are portrayed through images such as nature and travel using both ships and road to symbolize the importance of re-invention. -

Tolono Library CD List

Tolono Library CD List CD# Title of CD Artist Category 1 MUCH AFRAID JARS OF CLAY CG CHRISTIAN/GOSPEL 2 FRESH HORSES GARTH BROOOKS CO COUNTRY 3 MI REFLEJO CHRISTINA AGUILERA PO POP 4 CONGRATULATIONS I'M SORRY GIN BLOSSOMS RO ROCK 5 PRIMARY COLORS SOUNDTRACK SO SOUNDTRACK 6 CHILDREN'S FAVORITES 3 DISNEY RECORDS CH CHILDREN 7 AUTOMATIC FOR THE PEOPLE R.E.M. AL ALTERNATIVE 8 LIVE AT THE ACROPOLIS YANNI IN INSTRUMENTAL 9 ROOTS AND WINGS JAMES BONAMY CO 10 NOTORIOUS CONFEDERATE RAILROAD CO 11 IV DIAMOND RIO CO 12 ALONE IN HIS PRESENCE CECE WINANS CG 13 BROWN SUGAR D'ANGELO RA RAP 14 WILD ANGELS MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 15 CMT PRESENTS MOST WANTED VOLUME 1 VARIOUS CO 16 LOUIS ARMSTRONG LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB JAZZ/BIG BAND 17 LOUIS ARMSTRONG & HIS HOT 5 & HOT 7 LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB 18 MARTINA MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 19 FREE AT LAST DC TALK CG 20 PLACIDO DOMINGO PLACIDO DOMINGO CL CLASSICAL 21 1979 SMASHING PUMPKINS RO ROCK 22 STEADY ON POINT OF GRACE CG 23 NEON BALLROOM SILVERCHAIR RO 24 LOVE LESSONS TRACY BYRD CO 26 YOU GOTTA LOVE THAT NEAL MCCOY CO 27 SHELTER GARY CHAPMAN CG 28 HAVE YOU FORGOTTEN WORLEY, DARRYL CO 29 A THOUSAND MEMORIES RHETT AKINS CO 30 HUNTER JENNIFER WARNES PO 31 UPFRONT DAVID SANBORN IN 32 TWO ROOMS ELTON JOHN & BERNIE TAUPIN RO 33 SEAL SEAL PO 34 FULL MOON FEVER TOM PETTY RO 35 JARS OF CLAY JARS OF CLAY CG 36 FAIRWEATHER JOHNSON HOOTIE AND THE BLOWFISH RO 37 A DAY IN THE LIFE ERIC BENET PO 38 IN THE MOOD FOR X-MAS MULTIPLE MUSICIANS HO HOLIDAY 39 GRUMPIER OLD MEN SOUNDTRACK SO 40 TO THE FAITHFUL DEPARTED CRANBERRIES PO 41 OLIVER AND COMPANY SOUNDTRACK SO 42 DOWN ON THE UPSIDE SOUND GARDEN RO 43 SONGS FOR THE ARISTOCATS DISNEY RECORDS CH 44 WHATCHA LOOKIN 4 KIRK FRANKLIN & THE FAMILY CG 45 PURE ATTRACTION KATHY TROCCOLI CG 46 Tolono Library CD List 47 BOBBY BOBBY BROWN RO 48 UNFORGETTABLE NATALIE COLE PO 49 HOMEBASE D.J. -

Neil Young - July 21, 2015

Neil Young - July 21, 2015 Neil Young is taking his campaign against genetically modified foods to the next level with his upcoming album “The Monsanto Years” and a tour that stops at Nikon at Jones Beach Theater on July 21. Young has joined forces with Promise of the Real, which features Willie Nelson’s sons Lukas and Micah, for the album and the tour. “The Monsanto Years” is expected to include songs directed against Monsanto and Starbucks, which Young urged his fans to boycott last year for its part in trying to stop Vermont’s law requiring labels to disclose whether food has been genetically modified. Starbucks officials say they are not part of that effort. However, Young insists that the company is involved through the Grocery Manufacturers Association trade group. On June 16 Neil Young & Promise Of The Real will release a new studio album, The Monsanto Years, via Reprise Records. According to a statement, “the politically/ecologically-charged album will be released via participating digital retailers and Young’s online music store PonoMusic.com as well as on physical CD and vinyl in stores and through Neil’s official web store. The Monsanto Years is the first studio collaboration between Neil Young and L.A. rockers Promise Of The Real, a band fronted by Lukas Nelson (vocals/guitar) and Micah Nelson (guitar, 1 / 2 Neil Young - July 21, 2015 vocals), along with Anthony Logerfo (drums), Corey McCormick (bass) and Tato Melgar (percussion). Young & Promise Of The Real played a stealth show on Thursday in which they debuted a slew of material presumably from the new LP. -

Songs of the Century

Songs of the Century T. Austin Graham hat is the time, the season, the historical context of a popular song? When is it most present in the world, best able Wto reflect, participate in, or construct some larger social reality? This essay will consider a few possible answers, exploring the ways that a song can exist in something as brief as a passing moment and as broad as a century. It will also suggest that when we hear those songs whose times have been the longest, we might not be hearing “songs” at all. Most people are likely to have an intuitive sense for how a song can contract and swell in history, suited to a certain context but capable of finding any number of others. Consider, for example, the various uses to which Joan Didion is able to put music in her generation-defining essay “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” a meditation on drifting youth and looming apocalypse in the days of the Haight-Ashbury counterculture. Songs create a powerful sense of time and place throughout the piece, with Didion nodding to the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, Quick- silver Messenger Service, and “No Milk Today” by Herman’s Hermits, “a song I heard every morning in the cold late spring of 1967 on KRFC, the Flower Power Station, San Francisco.”1 But the music that speaks most directly and reverberates most widely in the essay is “For What It’s Worth,” the Buffalo Springfield single whose chiming guitar fifths and famous chorus—“Stop, hey, what’s that sound / Everybody look what’s going down”—make it instantly recognizable nearly five decades later.2 To listen to “For What It’s Worth” on Didion’s pages is to hear a song that exists in many registers and seems able to suffuse everything, from a snatch of conversation, to a set of political convictions, to nothing less than “The ’60s” itself. -

Reverend Billy & the Stop Shopping Choir

REVEREND BILLY & THE STOP SHOPPING CHOIR Rev and his choir now enrapture large audiences with sermons to which Jesus himself would have said Amen. - Kurt Vonnegut CONTACT: Thomas O. Kriegsmann, President E [email protected] T 917.386.5468 www.arktype.org ABOUT REVEREND BILLY & THE CHOIR Reverend Billy and the Stop Shopping Choir is a New York ter exorcisms, retail interventions, and cell phone operas. City based radical performance community, with 50 per- forming members and a congregation in the thousands. Outdoors, they have performed in Redwood forests, be- tween cars in traffic jams at the entrance to the Holland They are wild anti-consumerist gospel shouters and Tunnel, on the Staten Island Ferry, at Burning Man and Earth-loving urban activists who have worked with commu- Times Square and Coney Island, and on the roof of Car- nities on four continents defending community, life and negie Hall in a snowstorm. Under Savitri’s direction, the imagination. The Devils over the 15 years of their “church” choir has released CD’s, books and TV shows, among them have remained the same: Consumerism and Militarism. In the eight episodes of The Last Televangelist, created with this time of the Earth’s crisis - we are especially mindful of shooter-editor Glenn Gabel. In 2007 they co-produced with the extractive imperatives of global capital. Their activist Morgan Spurlock the acclaimed film What Would Jesus performances and concert stage performances have always Buy? - appearing on over 100 screens nationally and which worked in parallel. The activism is content for the play. has been broadcasted on Sundance Channel.