Photonics Handbook®

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

B.Sc. Mechatronics Specialization: Photonic Engineering

Study plan for: B.Sc. Mechatronics Specialization: Photonic Engineering Faculty of Mechatronics Study plan for reference only; may be subject to change. Semester 1 Course Lecture Tutorial Labs Pojects ECTS (hours) (hours) (hours) (hours) Physical Education and Sports 30 Patents and Intelectual Property 30 2 Optics and Photonics Applications 30 15 3 Calculus I 30 45 7 Algebra and Geometry 15 30 4 Engineering Graphics 15 30 2 Materials 30 2 Computer Science I 30 30 6 Engineering Physics 30 30 4 Total ECTS 30 Semester 2 Course Lecture Tutorial Labs Pojects ECTS (hours) (hours) (hours) (hours) Physical Education and Sports 30 Economics 30 2 Elective Lecture 1/Virtual and 30 3 Augmented Reality Calculus II 30 30 5 Engineering Graphics ‐ CAD 30 2 Computer Science II 15 15 5 Mechanics I i II 45 45 6 Mechanics of Structures I 30 15 4 Electric Circuits I 30 15 3 Total ECTS 30 1 Study Plan for B.Sc. Mechatronics (Spec. Photonic Engineering) Semester 3 Course Lecture Tutorial Labs Pojects ECTS (hours) (hours) (hours) (hours) Physical Education and Sports 30 0 Foreign Language 60 4 Elective Lecture 2/Introduction to 30 3 MEMS Calculus III 15 30 6 Mechanics of Structures II 15 15 4 Manufacturing Technology I 30 4 Fine Machine Design I 15 30 3 Electric Circuits II 30 3 Basics of Automation and Control I 30 15 4 Total ECTS 31 Semester 4 Course Lecture Tutorial Labs Pojects ECTS (hours) (hours) (hours) (hours) Physical Education and Sports 30 Foreign Language 60 4 Elective Lecture 3/Photographic 30 3 techniques in image acqusition Elective Lecture 4 30 3 /Enterpreneurship Optomechatronics 30 30 5 Electronics I 15 15 2 Electronics II 15 1 Fine Machine Design II 15 15 3 Manufacturing Technology 30 2 Metrology 30 30 4 Total ECTS 27 Semester 5 Course Lecture Tutorial Labs Pojects ECTS (hours) (hours) (hours) (hours) Physical Education and Sports 30 0 Foreign Language 60 4 Marketing 30 2 Elective Lecture 5/ Electric 30 2 2 Study Plan for B.Sc. -

Advanced Optics with Laser Pointer and Metersticks Roman Ya

Advanced Optics with Laser Pointer and Metersticks Roman Ya. Kezerashvili New York City College of Technology, The City University of New York 300 Jay Street, Brooklyn NY, 11201 Email: [email protected] Abstract We are using a laser pointer as a light source, and metersticks as an optical branch and the screen for wave optics experiments. It is shown the setup for measurements of wavelength of laser light and rating radial spacing of the CD, diffraction on a wire and a slit, observation of a polarization of light and observation of a hologram. 1. Introduction Laser pointers also know as laser penlights, have become very affordable recently due to new developments in laser technology. They are widely available at electronic stores, novelty shops, through mail order catalogs and by numerous other sources. They are in the price range from $1 to $30 as other electronic toys and are being treated as such by many parents and children. Pointers are used for other purposes such as the aligning of other lasers, laying pipes in construction, and as aiming devices for firearms. Laser pointer can be use to observe the interference, diffraction and polarization of light in college physics laboratory. Laser pointers can be used to produce holograms[1-2]. It been opinions it couldn't be done because of the short coherence of the beam and that laser pointer’s beam was not polarized. But it was practically proved that a laser pointer could be used not only to observe a hologram but to produce a high quality transmission and reflection display hologram[1-3]. -

Laser Pointer Safety About Laser Pointers Laser Pointers Are Completely Safe When Properly Used As a Visual Or Instructional Aid

Harvard University Radiation Safety Services Laser Pointer Safety About Laser Pointers Laser pointers are completely safe when properly used as a visual or instructional aid. However, they can cause serious eye damage when used improperly. There have been enough documented injuries from laser pointers to trigger a warning from the Food and Drug Administration (Alerts and Safety Notifications). Before deciding to use a laser pointer, presenters are reminded to consider alternate methods of calling attention to specific items. Most presentation software packages offer screen pointer options with the same features, but without the laser hazard. Selecting a Safe Laser Pointer 1) Choose low power lasers (Class 2) Whenever possible, select a Class 2 laser pointer because of the lower risk of eye damage. 2) Choose red-orange lasers (633 to 650 nm wavelength, choose closer to 635 nm) The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) researchers found that some green laser pointers can emit harmful levels of infrared radiation. The green laser pointers create green light beam in a three step process. A standard laser diode first generates near infrared light with a wavelength of 808nm, and pumps it into a ND:YVO4 crystal that converts the 808 nm light into infrared with a wavelength of 1064 nm. The 1064 nm light passes into a frequency doubling crystal that emits green light at a wavelength of 532nm finally. In most units, a combination of coatings and filters keeps all the infrared energy confined. But the researchers found that really inexpensive green lasers can lack an infrared filter altogether. One tested unit was so flawed that it released nine times more infrared energy than green light. -

Read About the Future of Packaging with Silicon Photonics

The future of packaging with silicon photonics By Deborah Patterson [Patterson Group]; Isabel De Sousa, Louis-Marie Achard [IBM Canada, Ltd.] t has been almost a decade Optics have traditionally been center design. Besides upgrading optical since the introduction of employed to transmit data over long cabling, links and other interconnections, I the iPhone, a device that so distances because light can carry the legacy data center, comprised of many successfully blended sleek hardware considerably more information off-the-shelf components, is in the process with an intuitive user interface that it content (bits) at faster speeds. Optical of a complete overhaul that is leading to effectively jump-started a global shift in transmission becomes more energy significant growth and change in how the way we now communicate, socialize, efficient as compared to electronic transmit, receive, and switching functions manage our lives and fundamentally alternatives when the transmission are handled, especially in terms of next- interact. Today, smartphones and countless length and bandwidth increase. As the generation Ethernet speeds. In addition, other devices allow us to capture, create need for higher data transfer speeds at as 5G ramps, high-speed interconnect and communicate enormous amounts of greater baud rate and lower power levels between data centers and small cells will content. The explosion in data, storage intensifies, the trend is for optics to also come into play. These roadmaps and information distribution is driving move closer to the die. Optoelectronic will fuel multi-fiber waveguide-to-chip extraordinary growth in internet traffic interconnect is now being designed interconnect solutions, laser development, and cloud services. -

Merging Photonics and Artificial Intelligence at the Nanoscale

Intelligent Nanophotonics: Merging Photonics and Artificial Intelligence at the Nanoscale Kan Yao1,2, Rohit Unni2 and Yuebing Zheng1,2,* 1Department of Mechanical Engineering, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas 78712, USA 2Texas Materials Institute, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas 78712, USA *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract: Nanophotonics has been an active research field over the past two decades, triggered by the rising interests in exploring new physics and technologies with light at the nanoscale. As the demands of performance and integration level keep increasing, the design and optimization of nanophotonic devices become computationally expensive and time-inefficient. Advanced computational methods and artificial intelligence, especially its subfield of machine learning, have led to revolutionary development in many applications, such as web searches, computer vision, and speech/image recognition. The complex models and algorithms help to exploit the enormous parameter space in a highly efficient way. In this review, we summarize the recent advances on the emerging field where nanophotonics and machine learning blend. We provide an overview of different computational methods, with the focus on deep learning, for the nanophotonic inverse design. The implementation of deep neural networks with photonic platforms is also discussed. This review aims at sketching an illustration of the nanophotonic design with machine learning and giving a perspective on the future tasks. Keywords: deep learning; (nano)photonic neural networks; inverse design; optimization. 1. Introduction Nanophotonics studies light and its interactions with matters at the nanoscale [1]. Over the past decades, it has received rapidly growing interest and become an active research field that involves both fundamental studies and numerous applications [2,3]. -

Experimental Photonics Multiple Post-Doctoral Positions Experimental Expertise in Any One of the Following Topics/Areas Is Highly Desired

Experimental Photonics Multiple Post-Doctoral Positions Experimental Expertise in any one of the following topics/areas is highly desired . Single photon level measurements , quantum communications . Computational imaging, super-resolution imaging, biomedical imaging . Quantum dots, 2D materials, quantum devices, quantum transport . Single molecule spectroscopy/imaging . Fluorescence microscopy . Optical manipulation of spin , ODMR, Magnetometry, NV centers . Nanofabication (Metasurfaces, plasmonics,silicon photonics) . Streak camera or time-correlated single photon counting experiments . Ultrafast spectroscopy, pump-probe measurements . Single nanoparticle/nanoantenna experiments . Coupling of single quantum emitters to nanophotonic structures . Cold atoms and quantum optics . Infrared spectroscopy, thermal emission measurements Please send your full CV and three representative publications to: [email protected] Prof. Zubin Jacob Birck Nanotechnology Center School of Electrical and Computer Engineering Purdue University, U.S.A. www.electrodynamics.org Zubin Jacob Research Group: Purdue University www.electrodynamics.org About the group Google Scholar Page: https://scholar.google.ca/citations?user=8FXvN_EAAAAJ&hl=en Main Research Areas: Casimir forces, quantum nanophotonics, plasmonics, metamaterials, Vacuum fluctuations, open quantum systems Weblink: www.electrodynamics.org Theory and Experiment Twitter: twitter.com/zjacob_group • Opportunity to closely interact with theorists and experimentalists within the group • Opportunity to travel -

Modeling Light Interactions with Matter (Liquid Solutions)

Modeling Light Interactions with Matter (liquid solutions) Author(s): David Deutsch Date Created: July 31, 2015 (Revised June 22, 2017) Subject: Physics Grade Level: High School Standards: Next Generation Science Standards (www.nextgenscience.org) HS-PS4-5 Communicate technical information about how some technological devices use the principles of wave behavior and wave interactions with matter to transmit and capture information and energy Schedule: Two 45 minute periods CCMR Lending Library Connected Activities: Diffraction DNA and the Diffraction of Light (CIPT) The Phantastic Photon and LEDs (CIPT) Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) license. - 1 – Objectives: Vocabulary: Laser pointers of several frequencies, · transmission index cards, and a small transparent · scattering container of extra virgin olive oil can be · absorption used to investigate the interaction of · fluorescence light with particles in solution. One can describe the observed phenomena · Stokes Shift operationally in terms of brightness, color, and direction or from a photon – particle perspective. Students Will: Materials: 1. Operationally define scattering, - Two plain white index cards transmission, absorption, and - One small, transparent container of fluorescence. extra virgin olive oil 2. Develop a photon/energy level - Laser pointers (green, red, blue/violet) model for absorption and fluorescence. 3. Interpret absorption and emission spectra and define the Stokes Shift The laser pointers used can damage Safety tissue, especially in the eye. Care must be taken to assure that laser light is aimed only at the targets intended in this activity Science Content for the Teacher: When light encounters matter (such as particles in a solution), there are several phenomena which may occur. -

Photonics Engineer

Photonics Engineer Antelope company Antelope DX develops a point-of-need diagnostic platform that allows consumers and healthcare professionals to have on-the-spot access to key health parameters. The Antelope technology aims to offer clinical lab performance with the ease-of-use of a pregnancy test at a consumer price tag. The platform is based on an innovative lab-on-chip technology that can perform a sensitive test on any bodily fluid, without requiring complex user operations or sample preparation. Role The Antelope Photonics Engineer is responsible for the design & development of the silicon photonic chip, located inside the Antelope consumable. He/she will also contribute largely to the optics and photonics aspects of associated hardware such as the Antelope reader. He/she will need to perform these product developments in a way that is compatible to IVD industry standards, including the generation of associated documentation. Responsibilities and duties • Photonics design & optimization of the sensing circuits. • Set up an optical/photonic system model to better predict and understand deviations from the norm by e.g. manufacturing tolerances. • Setting up characterisation, verification and QC equipment and methodologies for the photonic wafers & chips. • Support the design of the optical components of the read-out system. • Support the developmentt of the algorithmic framework that processes the optical signals to a diagnostic answer. • Support the development of R&D tools & methodologies from a system perspective to increase R&D efficiency, throughput and data generation. • Support the improvement of the R&D experimental setups, used to generate assay results. • Setting up testing and verification planning. -

Laser Pointer Safety

Laser Pointer Safety INTRODUCTION The use of laser diode pointers that operate in the visible radiation region (400 to 760 nanometers [nm]) is becoming widespread. These pointers are intended for use by educators while presenting talks in the classroom or at conventions and meetings. A high-tech alternative to the retractable, metal pointer, the laser pointer beam will produce a small dot of light on whatever object at which it is aimed. It can draw an audience¹s attention to a particular key point in a slide show. Laser pointers are not regulated at Oklahoma State University although the university has a Laser Safety Committee. Only Class IIIb and Class IV lasers are covered under OSU’s Laser Safety Program. The power emitted by these laser pointers ranges from 1 to 5 milliwatts (mW). Laser Pointers are similar to devices used for other purposes such as the aligning of other lasers, laying pipes in construction, and as aiming devices for firearms. They are widely available at electronic stores, novelty shops, through mail order catalogs and by numerous other sources. At $20 or even less, laser pointers are in the price range of other electronic toys and have been treated as such by many parents and children. Laser Pointers are not toys! Although most of these devices contain warning labels, as required by FDA regulations, many have been erroneously advertised as "safe". The potential for hazard with laser pointers is generally considered to be limited to the unprotected eyes of individuals who might be exposed by a direct beam (intrabeam viewing). -

Illuminating the History and Expanding Photonics Education

Illuminating the History and Expanding Photonics Education An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science by Nicholas Marshall Brandon McLaughlin Date: 2nd June 2020 Report Submitted to: Worcester Polytechnic Institute Quinsigamond Community College Professor Douglas Petkie Worcester Polytechnic Institute This report represents work of WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial or peer review. For more information about the projects program at WPI, see http://www.wpi.edu/Academics/Projects. Abstract Photonics today is on the cusp of revolutionizing computing, just as it has already revolutionized communication, and becoming to this century what electricity was to the last (Sala, 2016). As the manifestation of mankind's millenia-spanning obsession with light, photonics evolved from optics, which itself developed over the long course of human history. That development has accelerated in the last several centuries, and today optics and photonics act as enablers for a variety of fields from biology to communication. Even so, most people don’t know just how essential optics and photonics are, and today those fields face a major staffing shortage. Most people don’t even know the basic principles of light’s behavior, with few formal education programs that focus on optics and photonics. In order to combat this, various initiatives have strived to drum up more interest in optics and photonics, with several focusing on pre-college age groups in order to get students involved sooner. -

The Role of Nanostructures in Integrated Photonics

The role of Nanostructures in Integrated Photonics James S. Harris Department of Electrical Engineering Stanford University 3rd U.S.-Korea Forum on Nanotechnology Seoul, Korea April 3 & 4, 2006 U.S.-Korea Forum on Nanotechnology-Korea-4/3/06 JSH 1 1993 Photonic Integrated Circuit Soref, Proc. IEEE, 1687 (1993) z Waveguide architecture with butt coupled fibers and edge emitting lasers z Hybrid bonding (non-monolithic) of different structures z Mostly III-V devices, very little electronics U.S.-Korea Forum on Nanotechnology-Korea-4/3/06 JSH 2 First Photonic Crystal Device DBR (Distributed Bragg Reflector z Single longitudinal mode emission, z 20-40 quarter wavelength independent of temperature and current injection different index layers (~70 nm) z Circular beam pattern z One-dimensional photonic crystal z Vertical emission--2-D array U.S.-Korea Forum on Nanotechnology-Korea-4/3/06 JSH 3 Dimensional Mismatch Between Optics and Electronics U.S.-Korea Forum on Nanotechnology-Korea-4/3/06 JSH 4 Unique Photonic Crystal Functionality Electric Field Strength U.S.-Korea Forum on Nanotechnology-Korea-4/3/06 JSH 5 Nanoscale Plasmonic Waveguides z 90° bends and splitters can be designed with 100% transmission from microwave to optical frequencies z Provides bridge between dimensions of electronics and photonics z Provides design flexibility for optoelectronic ICs U.S.-Korea Forum on Nanotechnology-Korea-4/3/06 JSH 6 A New Si-Based Optical Modulator Quantum-confined Stark effect (QCSE) z Strongest high-speed optical modulation mechanism z Used today for high-speed, low power telecommunications optical modulators but in III-V semiconductors z QCSE in germanium quantum wells on silicon substrates z Fully compatible with CMOS fabrication z Surprises z works in “indirect gap” semiconductor actually better than in III-V z higher speed (100 GHz) possible Y. -

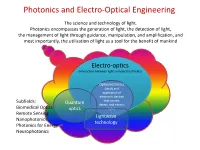

Photonics and Electro-Optical Engineering

Photonics and Electro-Optical Engineering The science and technology of light. Photonics encompasses the generation of light, the detection of light, the management of light through guidance, manipulation, and amplification, and most importantly, the utilization of light as a tool for the benefit of mankind Electro-optics (interaction between light and electrical fields) Optoelectronics (study and application of electronic devices Subfields: that source, Quantum detect, and control Biomedical Optics optics light) Remote Sensing Lightwave Nanophotonics technology Photonics for Energy Neurophotonics Photonics and Electro-Optical Engineering Photonics is an enabling technology1 with general-purpose characteristics applications in : • Communications, information processing and data storage • Health and medicine • Energy • Defense and homeland security • Advanced manufacturing • Advanced metrology 1 enabling general-purpose technology – technology that advances foster innovations across a broad spectrum of applications in a diverse array of economic sectors. Other examples of general-purpose enabling technologies are the transistor and the integrated circuit. Photonics engineering –an enabling technology Not always seen but it is ubiquitous . Consider for example using a smartphone to perform an Internet search. Where is the optics? Efficient Flash light Smart Camera High resolution display cell tower Microprocessor fabricated using optical lithographic techniques fiber optic network Chips inspected with photonics techniques more than 1 million lasers involved in the data signaling Data center 20km of fibers Photonics and Electro-Optical Engineering in the 21st century The term of photonics was coined in analogy with electronics: Electronics involves the control of electric-charge flow (in vacuum or matter); Photonics involves the control of photons (in free space and matter) It is expected that the 21st century will depend as much on photonics as the 20th century depended on electronics1.