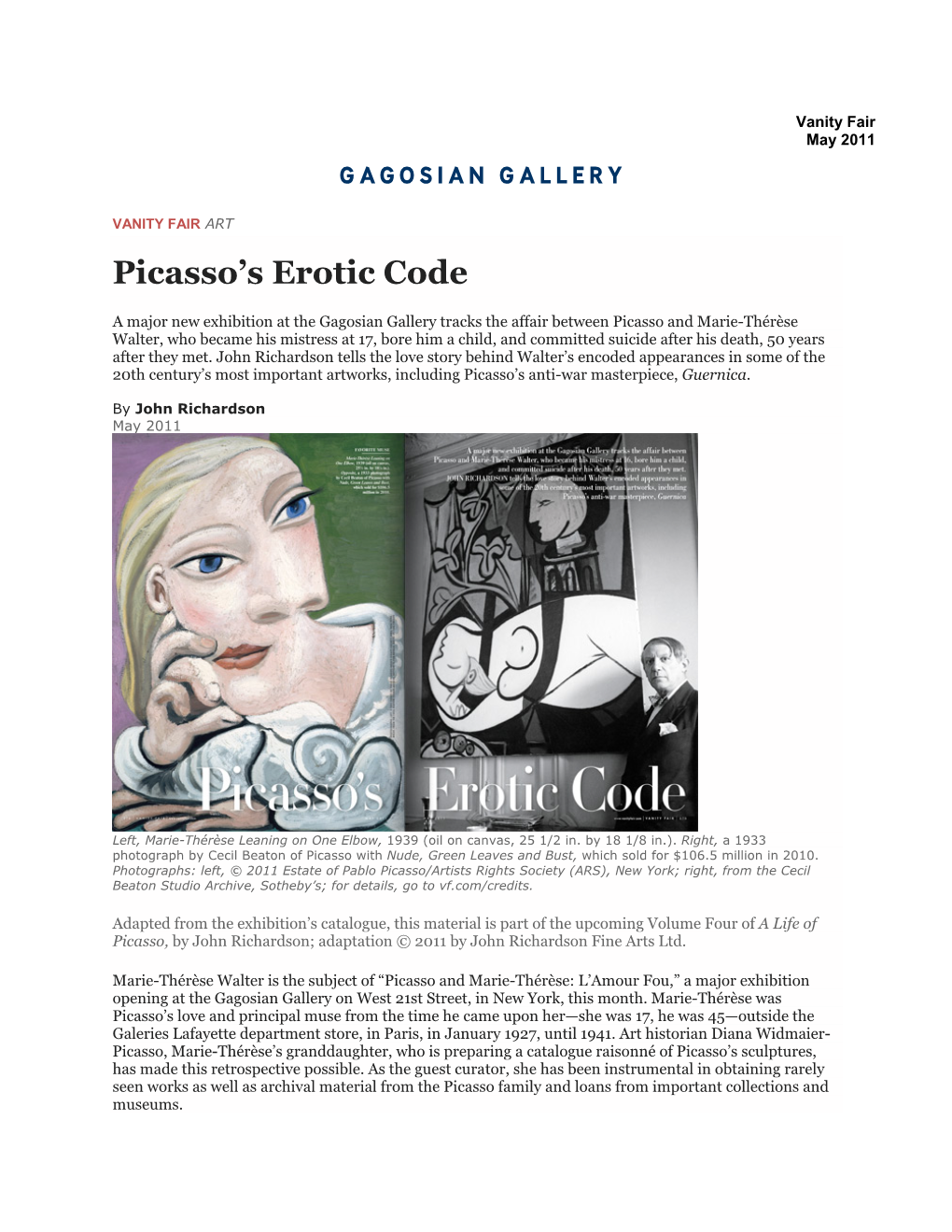

Picasso's Erotic Code by John Richardson Vanity Fair

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Objects Proposed for Protection Under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (Protection of Cultural Objects on Loan)

List of objects proposed for protection under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (protection of cultural objects on loan) Picasso and Paper 25 January 2020 to 13 April 2020 Arist: Pablo Picasso Title: Self-portrait Date: 1918-1920 Medium: Graphite on watermarked laid paper (with LI countermark) Size: 32 x 21.5 cm Accession: n°00776 Lender: BRUSSELS, FUNDACIÓN ALMINE Y BERNARD RUIZ-PICASSO PARA EL ARTE 20 rue de l'Abbaye Bruxelles 1050 Belgique © FABA Photo: Marc Domage PROVENANCE Donation by Bernard Ruiz-Picasso; estate of the artist; previously remained in the possession of the artist until his death, 1973 Note that: This object has a complete provenance for the years 1933-1945 List of objects proposed for protection under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (protection of cultural objects on loan) Picasso and Paper 25 January 2020 to 13 April 2020 Arist: Pablo Picasso Title: Mother with a Child Sitting on her Lap Date: December 1947 Medium: Pastel and graphite on Arches-like vellum (with irregular pattern). Invitation card printed on the back Size: 13.8 x 10 cm Accession: n°11684 Lender: BRUSSELS, FUNDACIÓN ALMINE Y BERNARD RUIZ-PICASSO PARA EL ARTE 20 rue de l'Abbaye Bruxelles 1050 Belgique © FABA Photo: Marc Domage PROVENANCE Donation by Bernard Ruiz-Picasso; Estate of the artist; previously remained in the possession of the artist until his death, 1973 Note that: This object was made post-1945 List of objects proposed for protection under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (protection of cultural objects on loan) Picasso and Paper 25 January 2020 to 13 April 2020 Arist: Pablo Picasso Title: Little Girl Date: December 1947 Medium: Pastel and graphite on Arches-like vellum. -

Pablo Picasso's 1954 Portrait of Muse, Jacqueline Roque, to Highlight Christie's November Evening Sale of Impressionist &

PRESS RELEASE | N E W Y O R K FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: 14 SEPTEMBER 2017 PABLO PICASSO’S 1954 PORTRAIT OF MUSE, JACQUELINE ROQUE, TO HIGHLIGHT CHRISTIE’S NOVEMBER EVENING SALE OF IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART To be Sold in New York, 13 November 2017 Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), Femme accroupie (Jacqueline), Painted on 8 October 1954 Oil on canvas, 57 1/2 x 44 7/8 in. | Estimate: $20-30 million © 2017 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York New York – Christie’s will offer Pablo Picasso’s Femme accroupie (Jacqueline), painted on October 8, 1954 as a central highlight of its Evening Sale of Impressionist and Modern Art on 13 November in New York. Marking its first time at auction, Femme accroupie (Jacqueline) comes from a private collection, and is estimated to sell for $20-30 million. The work will be on public view at Christie’s London from 16 - 19 September, and at Christie’s Hong Kong from 28 September - 3 October. Christie’s Global President, Jussi Pylkkanen, remarked, “Jacqueline was a beautiful woman and one of Picasso’s most elegant muses. This painting of Jacqueline hung in Picasso’s private collection for many years and has rarely been seen in public since 1954. It is a museum quality painting on the grand scale which will capture the imagination of the global art market when it is offered at Christie’s New York this November.” The brilliant primary colors in Femme accroupie (Jacqueline) illustrate a sunny day in the South of France during early autumn, 1954. -

Narcissism, Vanity, Personality and Mating Effort

Personality and Individual Differences 43 (2007) 2105–2115 www.elsevier.com/locate/paid Narcissism, vanity, personality and mating effort Vincent Egan *, Cara McCorkindale Department of Psychology, Glasgow Caledonian University, Cowcaddens Road, Glasgow G4 0BA, Scotland, United Kingdom Received 10 November 2006; received in revised form 19 June 2007; accepted 27 June 2007 Available online 15 August 2007 Abstract The current study examined the relationship between narcissism and vanity, and the degree these are pre- dicted by the ‘Big Five’ personality traits and mating effort (ME) using a sample of 103 females recruited from a large beauty salon. Narcissism correlated with vanity at 0.72 (P < 0.001), and was associated pos- itively with extraversion (E), ME and the subscales of vanity; narcissism was associated negatively with neu- roticism (N) and agreeableness (A). Vanity correlated positively with E, conscientiousness, both subscales of narcissism, and ME, and negatively with N and A. A composite narcissism–vanity score was produced using principal components analysis, and used along with scores from the NEO-FFI-R to predict mating effort. The narcissism–vanity composite, low A and E significantly and independently predicted mating effort (adjusted R2 = 0.28, F(9.96) = 7.74, P < 0.001). These results show that mating effort is additionally predicted by narcissism as well as self-reported personality. Ó 2007 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: Narcissism; Personality; Mating effort; Vanity; Self-enhancement; Beauty 1. Introduction Although narcissism forms one third of the ‘dark triad’ of personality and is associated with low agreeableness (A) and other unpleasant aspects of character (Jakobwitz & Egan, 2006), * Corresponding author. -

Artist Resources – Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881-1973) Musée Picasso, Paris Picasso at Moma

Artist Resources – Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881-1973) Musée Picasso, Paris Picasso at MoMA Picasso talks Communism, visual perception, and inspiration in this intimate interview at his home in Cannes in 1957. “My work is a constructive one. I am Building, not tearing down. What people call deformation in my work results from their own misapprehension. It's not a matter of deformation; it's a question of formation. My work oBeys laws I have spent my life in formulating and adhering to. EveryBody has a different idea of what constitutes reality and the suBstance of things….I set [oBjects] down in what my intellect tells me is the order and form in which they appear to me.” In these excerpts from 1943, from his Book, Conversations with Picasso, French photographer and sculpture Brassaï reflects candidly with his friend and contemporary aBout Building on the past, authenticity, and gathering inspiration from nature, history, and museums. “I thought I learned a lot from him. Mostly in terms of the way he worked, the concentration in which he worked, the unity of spirit in thinking in thinking aBout nothing else, giving everything away for that,” reflected Françoise Gilot in an interview with Charlie Rose in 1998. In 2019, she puBlished the groundBreaking memoir of her own life as an artist and her relationship with the untamaBle master, Life with Picasso. MoMA’s monumental 1996 exhiBition Picasso and Portraiture: Representation and Transformation emBarked on a Picasso in his Montmartre studio, 1908 tour of over 200 visual representations By the artist of his friends, family, and contemporaries. -

Menu of Services

Menu of Services Chuan Spa at The Langham Huntington, Pasadena Welcome to Chuan Spa. Here you will find an oasis of tranquility just minutes away from Los Angeles and Hollywood. The soothing setting inspires contemplation and introspection as you embark upon a journey to balance the mind, body and soul. In Chinese, Chuan means flowing water. As the source of life, water represents the re-birth and re-balancing of our whole being. Begin your Chuan Spa journey at our Contemplation Lounge, where you will identify your element of the day. Enter through the Moon Gate and proceed into our luxurious changing facilities to enjoy the heat experiences prior to your spa services. Indulge in one of our signature holistic treatments designed to restore peace and harmony. Complete your journey to wellness resting in our exquisite Dream Room, while enjoying one of our Chinese five element teas. The Five Elements Exclusive to Chuan Spa at The foundation of our Chuan Spa signature treatments is The Langham Huntington, Pasadena Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) and the five elemental Chuan Spa at The Langham Huntington, Pasadena features forces of wood, fire, earth, metal and water. These life the finest product lines for men and women along with elements combined with your energy flow and the influence exclusive services that have been created especially for of heat experiences have great impact on your well-being. Chuan Spa to enhance your journey. Our partners include Spend a moment to complete a five element questionnaire Kerstin Florian, EmerginC, Elemis, Immunocologie, at the beginning of your journey to ensure your therapist HydraFacial MD®, Morgan Taylor, Kryolan, Kevin Murphy addresses the imbalances of your life elements. -

I. Introduction A. When Kent Keller and I Wrote Our Modesty Book, We

I. Introduction A. When Kent Keller and I wrote our modesty book, we originally entitled it A Gold Ring in a Pig’s Snout. I still like that title but the publisher had major objections, so we changed it. But what we were thinking was based on Proverbs 11:22 “As a ring of gold in a Swine’s snout so is a beautiful woman who lacks discretion (moral perception).” B. For this session, I want to: 1) Define biblical modesty and immodesty. 2) What the Bible teaches about modesty. 3) Practical tips on how not to look like a beautiful gold ring all dressed up outwardly to go to a party but in your heart you look to God like you are an ugly pig. II. Definition of modesty and immodesty A. Modesty: An inner attitude of the heart motivated by a love for God that seeks His glory through purity and humility; it often reveals itself in words, actions, expressions, and clothes. B. Immodesty: An attitude of the heart that expresses itself with inappropriate words, actions, expressions and/or clothes that are flirtatious, manipulative, revealing, or suggestive of sensuality or pride. III. What the Bible Teaches About Modesty A. God created men and women to be different. Genesis 2:18, 21-25 B. Along came sin and everything became tainted by sin, not only for Adam and Eve but for all of their children including us. Genesis 3:7 C. When sin entered the picture so did sexual lust, vanity, sensuality, immorality, and all kinds of associated sins. -

Pablo Picasso - the Artist and His Muse

Pablo Picasso - The Artist and His Muse Pablo Picasso defined Modern Art just as Einstein defined the word "scientist." Picasso was the ambassador of Cubism and Abstract Art. However, greater the fame he achieved with his brush, the more degenerate his relationships became. Pablo Picasso's art reflected all his failed relationships, infidelity, vengefulness and emotional sourness, which made him world famous. Pablo Picasso faced his first tragedy at the death of his sister, Conchita, when he was just seventeen. This left a very deep impression on him. Although Pablo was never as desperate as Goya or Van Gogh or Gauguin, he had his share of mistresses and lovers. Most of Pablo's relationships with them ended bitterly and many which started as a hero worship ended with the accusations of infidelity and abuse. This story repeated itself several times, as Picasso's art grew from Realism to Blue, Rose, Africanism, and Cubism. The funniest part was that, as Pablo Picasso seems to have "phases" in his art; his women also were "in phases." For every segment of his works, it is easy to recognize a different woman. Pablo Picasso's first long-term mistress was Fernande Olivier, who was a fellow artist of his. Olivier was the muse, who graced his "Rose" period works. The colors in Rose Phase Paintings were primarily bright Orange, and Pink. Happy characters such as, Circus Artisans and Harlequins graced Pablo Picasso's Canvas. It could be said that maybe the young Picasso was in love. However, as his art gained value, he left Olivier for Eva (Marcelle Humbart), now making her the queen of his "Cubist" works. -

Picasso Et La Famille 27-09-2019 > 06-01-2020

Picasso et la famille 27-09-2019 > 06-01-2020 1 Cette exposition est organisée par le Musée Sursock avec le soutien exceptionnel du Musée national Picasso-Paris dans le cadre de « Picasso-Méditerranée », et avec la collaboration du Ministère libanais de la Culture. Avec la généreuse contribution de Danièle Edgar de Picciotto et le soutien de Cyril Karaoglan. Commissaires de l’exposition : Camille Frasca et Yasmine Chemali Scénographie : Jacques Aboukhaled Graphisme de l’exposition : Mind the gap Éclairage : Joe Nacouzi Graphisme de la publication et photogravure : Mind the gap Impression : Byblos Printing Avec la contribution de : Tinol Picasso-Méditerranée, une initiative du Musée national Picasso-Paris « Picasso-Méditerranée » est une manifestation culturelle internationale qui se tient de 2017 à 2019. Plus de soixante-dix institutions ont imaginé ensemble une programmation autour de l’oeuvre « obstinément méditerranéenne » de Pablo Picasso. À l’initiative du Musée national Picasso-Paris, ce parcours dans la création de l’artiste et dans les lieux qui l’ont inspiré offre une expérience culturelle inédite, souhaitant resserrer les liens entre toutes les rives. Maternité, Mougins, 30 août 1971 Huile sur toile, 162 × 130 cm Musée national Picasso-Paris. Dation Pablo Picasso, 1979. MP226 © RMN-Grand Palais / Adrien Didierjean © Succession Picasso 2019 L’exposition Picasso et la famille explore les rapports de Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) à la notion de noyau familial, depuis la maternité jusqu’aux jeux enfantins, depuis l’image d’une intimité conceptuelle à l’expérience multiple d’une paternité sous les feux des projecteurs. Réunissant dessins, gravures, peintures et sculptures, l’exposition survole soixante-dix-sept ans de création, entre 1895 et 1972, au travers d’une sélection d’œuvres marquant des points d’orgue dans la longue vie familiale et sentimentale de l’artiste et dont la variété des formes illustre la réinvention constante du vocabulaire artistique de Picasso. -

Picasso בין השנים 1899-1955

http://www.artpane.com קטלוג ואלבום אמנות המתעד את עבודותיו הגרפיות )ליתוגרפיות, תחריטים, הדפסים וחיתוכי עץ( של פאבלו פיקאסו Pablo Picasso בין השנים 1899-1955. מבוא מאת ברנארד גיסר Bernhard Geiser בהוצאת Thames and Hudson 1966 אם ברצונכם בספר זה התקשרו ואשלח תיאור מפורט, מחיר, אמצעי תשלום ואפשרויות משלוח. Picasso - His graphic Work Volume 1 1899-1955 - Thames and Hudson 1966 http://www.artpane.com/Books/B1048.htm Contact me at the address below and I will send you further information including full description of the book and the embedded lithographs as well as price and estimated shipping cost. Contact Details: Dan Levy, 7 Ben Yehuda Street, Tel-Aviv 6248131, Israel, Tel: 972-(0)3-6041176 [email protected] Picasso - His graphic Work Volume 1 1899-1955 - Introduction by Bernhard Geiser Pablo Picasso When Picasso talks about his life - which is not often - it is mostly to recall a forgotten episode or a unique experience. It is not usual for him to dwell upon the past because he prefers to be engaged in the present: all his thoughts and aspirations spring from immediate experience. It is on his works - and not least his graphic work - therefore, that we should concentrate in order to learn most about him. A study of his etchings, lithographs, and woodcuts reveals him in the most personal and intimate aspect. I cannot have a print of his in my hand without feeling the artist’s presence, as if he himself were with me in the room, talking, laughing, revealing his joys and sufferings. Daniel Henry Kahnweiler once said: “With Picasso, art is never mere rhetoric, his work is inseparable from his life... -

RCEWA Case Xx

Reviewing Committee on the Export of Works of Art and Objects of Cultural Interest: Note of case hearing on 18 July 2012: A painting by Pablo Picasso, Child with a Dove (Case 3, 2012-13) Application 1. The Reviewing Committee on the Export of Works of Art and Objects of Cultural Interest (RCEWA) met on 18 July 2012 to consider an application to export a painting by Pablo Picasso, Child with a Dove. The value shown on the export licence application was £50,000,000, which represented the sale price. The expert adviser had objected to the export of the painting under the first, second and third Waverly criteria i.e. on the grounds that it was so closely connected with our history and national life that its departure would be a misfortune, that it was of outstanding aesthetic importance and that it was of outstanding significance for the study of the birth of modernism and the reception of modernism in the UK. 2. The seven regular RCEWA members present were joined by three independent assessors, acting as temporary members of the Reviewing Committee. 3. The applicant confirmed that the value did include VAT and that VAT would be payable in the event of a UK sale. The applicant also confirmed that the owner understood the circumstances under which an export licence might be refused and that, if the decision on the licence was deferred, the owner would allow the painting to be displayed for fundraising. Expert’s submission 4. The expert had provided a written submission stating that the painting, Child with a Dove, was one of the earliest and most important works by Picasso to enter a British collection. -

Pablo Picasso

Famous Artists In thirty seconds, tell your partner the names of as many famous artists as you can think of. 30stop Pablo Picasso th ArePablo you Picasso named was after born aon family 25 October member 1881. or someone special? He was born in Malaga in Spain. Did You Know? Picasso’s full surname was Ruiz y Picasso. ThisHis full follows name thewas SpanishPablo Diego custom José Franciscowhere people de havePaula two Juan surnames. Nepomuceno The María first de is losthe Remedios first part ofCipriano their dad’sde la Santísimasurname, Trinidad the second Ruiz isy thePicasso. first He was named after family members and special partreligious of their figures mum’s known surname. as saints. Talk About It Picasso’s Early Life Do you know what your first word was? Words like ‘mama’ and ‘dada’ are common first words. However, Picasso’s mum said his first word was ‘piz’, short for ‘lapiz’, the Spanish word for pencil. Cubism Along with an artist called Georges Braque, Picasso started a new style of art called Cubism. Cubism is a style of art which aims to show objects and people from lots of different angles all at one time. This is done through the use of cubes and other shapes. Here are some examples of Picasso’s cubist paintings. What do you think about each of these paintings? Talk About It DanielWeeping-HenryMa Jolie, Woman,Kahnweiler, 1912 1937 1910 Picasso’s Different Styles ThroughoutHow do these his paintings life, Picasso’s make artyou took feel? on differentHow do you styles. think Picasso was feeling when he painted them? One of the most well known of these phases was known as his ‘blue period’. -

Pablo Picasso, One of the Most He Was Gradually Assimilated Into Their Dynamic and Influential Artists of Our Stimulating Intellectual Community

A Guide for Teachers National Gallery of Art,Washington PICASSO The Early Ye a r s 1892–1906 Teachers’ Guide This teachers’ guide investigates three National G a l l e ry of A rt paintings included in the exhibition P i c a s s o :The Early Ye a rs, 1 8 9 2 – 1 9 0 6.This guide is written for teachers of middle and high school stu- d e n t s . It includes background info r m a t i o n , d i s c u s s i o n questions and suggested activities.A dditional info r m a- tion is available on the National Gallery ’s web site at h t t p : / / w w w. n g a . gov. Prepared by the Department of Teacher & School Programs and produced by the D e p a rtment of Education Publ i c a t i o n s , Education Division, National Gallery of A rt . ©1997 Board of Tru s t e e s , National Gallery of A rt ,Wa s h i n g t o n . Images in this guide are ©1997 Estate of Pa blo Picasso / A rtists Rights Society (ARS), New Yo rk PICASSO:The EarlyYears, 1892–1906 Pablo Picasso, one of the most he was gradually assimilated into their dynamic and influential artists of our stimulating intellectual community. century, achieved success in drawing, Although Picasso benefited greatly printmaking, sculpture, and ceramics from the artistic atmosphere in Paris as well as in painting. He experiment- and his circle of friends, he was often ed with a number of different artistic lonely, unhappy, and terribly poor.