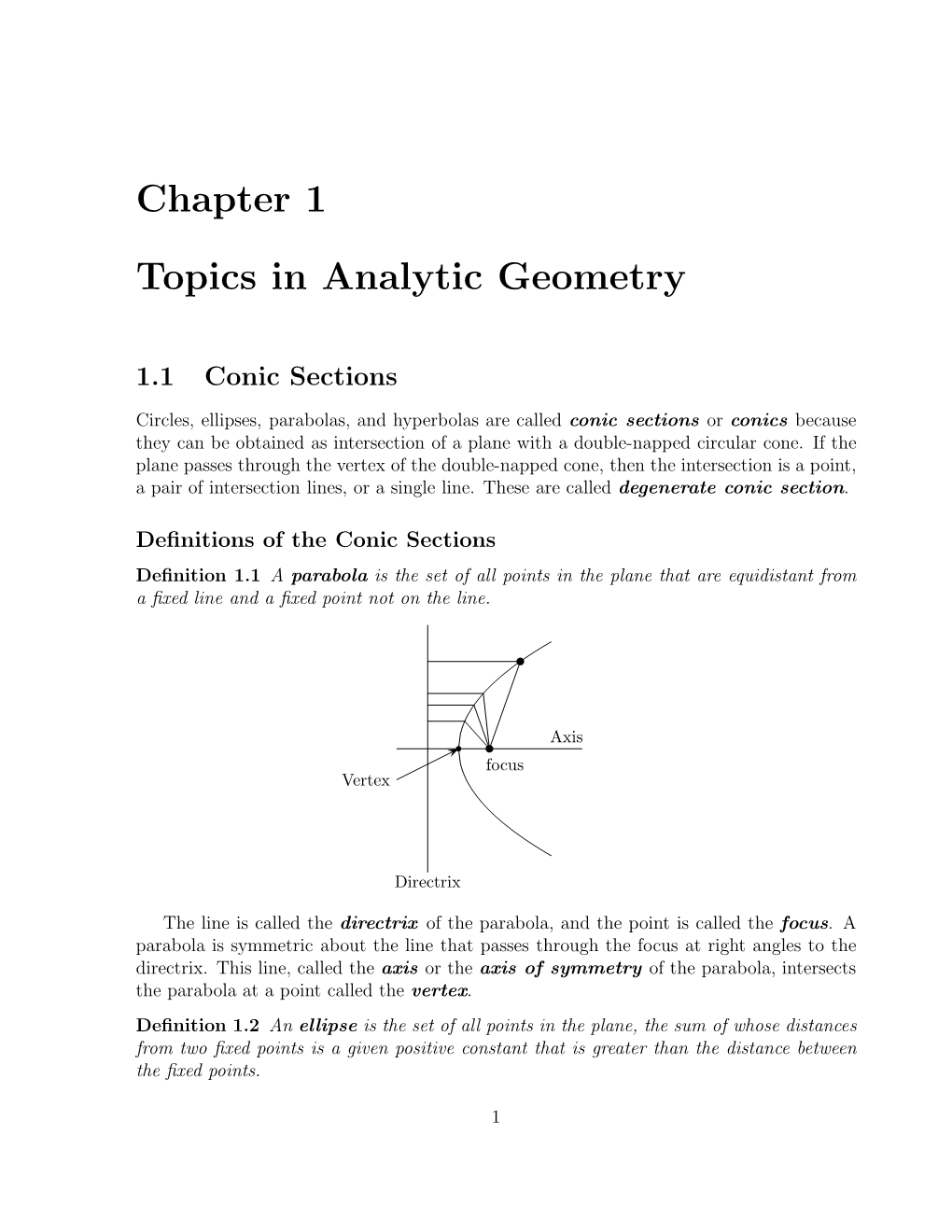

Chapter 1 Topics in Analytic Geometry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 1 Geometry of Plane Curves

Chapter 1 Geometry of Plane Curves Definition 1 A (parametrized) curve in Rn is a piece-wise differentiable func- tion α :(a, b) Rn. If I is any other subset of R, α : I Rn is a curve provided that α→extends to a piece-wise differentiable function→ on some open interval (a, b) I. The trace of a curve α is the set of points α ((a, b)) Rn. ⊃ ⊂ AsubsetS Rn is parametrized by α if and only if there exists set I R ⊂ ⊆ such that α : I Rn is a curve for which α (I)=S. A one-to-one parame- trization α assigns→ and orientation toacurveC thought of as the direction of increasing parameter, i.e., if s<t,the direction of increasing parameter runs from α (s) to α (t) . AsubsetS Rn may be parametrized in many ways. ⊂ Example 2 Consider the circle C : x2 + y2 =1and let ω>0. The curve 2π α : 0, R2 given by ω → ¡ ¤ α(t)=(cosωt, sin ωt) . is a parametrization of C for each choice of ω R. Recall that the velocity and acceleration are respectively given by ∈ α0 (t)=( ω sin ωt, ω cos ωt) − and α00 (t)= ω2 cos 2πωt, ω2 sin 2πωt = ω2α(t). − − − The speed is given by ¡ ¢ 2 2 v(t)= α0(t) = ( ω sin ωt) +(ω cos ωt) = ω. (1.1) k k − q 1 2 CHAPTER 1. GEOMETRY OF PLANE CURVES The various parametrizations obtained by varying ω change the velocity, ac- 2π celeration and speed but have the same trace, i.e., α 0, ω = C for each ω. -

Tangent Lines

The Kabod Volume 5 Issue 1 Fall 2018 Article 1 September 2018 Tangent Lines Samuel Estep Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/kabod Part of the Mathematics Commons Recommended Citations MLA: Estep, Samuel "Tangent Lines," The Kabod 5. 1 (2018) Article 1. Liberty University Digital Commons. Web. [xx Month xxxx]. APA: Estep, Samuel (2018) "Tangent Lines" The Kabod 5( 1 (2018)), Article 1. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/kabod/vol5/iss1/1 Turabian: Estep, Samuel "Tangent Lines" The Kabod 5 , no. 1 2018 (2018) Accessed [Month x, xxxx]. Liberty University Digital Commons. This Individual Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Kabod by an authorized editor of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Estep: Tangent Lines Tangent Lines Sam Estep 2018-05-06 In [1] Leibniz published the first treatment of the subject of calculus. An English translation can be found in [2]; he says that to find a tangent is to draw a right line, which joins two points of the curve having an infinitely small difference, or the side of an infinite angled polygon produced, which is equivalent to the curve for us. Today, according to [3], a straight line is said to be a tangent line of a curve y = f(x) at a point x = c on the curve if the line passes through the point (c; f(c)) on the curve and has slope f 0(c) where f 0 is the derivative of f. -

Sources and Studies in the History of Mathematics and Physical Sciences

Sources and Studies in the History of Mathematics and Physical Sciences Editorial Board J.Z. Buchwald J. Lützen G.J. Toomer Advisory Board P.J. Davis T. Hawkins A.E. Shapiro D. Whiteside Springer Science+Business Media, LLC Sources and Studies in the History of Mathematics and Physical Seiences K. Andersen Brook Taylor's Work on Linear Perspective H.l.M. Bos Redefining Geometrical Exactness: Descartes' Transformation of the Early Modern Concept of Construction 1. Cannon/S. Dostrovsky The Evolution of Dynamics: Vibration Theory from 1687 to 1742 B. ChandIerlW. Magnus The History of Combinatorial Group Theory A.I. Dale AHistory of Inverse Probability: From Thomas Bayes to Karl Pearson, Second Edition A.I. Dale Most Honourable Remembrance: The Life and Work of Thomas Bayes A.I. Dale Pierre-Simon Laplace, Philosophical Essay on Probabilities, Translated from the fifth French edition of 1825, with Notes by the Translator P. Damerow/G. FreudenthallP. McLaugWin/l. Renn Exploring the Limits of Preclassical Mechanics: A Study of Conceptual Development in Early Modem Science: Free Fall and Compounded Motion in the Work of Descartes, Galileo, and Beeckman, Second Edition P.l. Federico Descartes on Polyhedra: A Study of the De Solworum Elementis B.R. Goldstein The Astronomy of Levi ben Gerson (1288-1344) H.H. Goldstine A History of Numerical Analysis from the 16th Through the 19th Century H.H. Goldstine A History of the Calculus of Variations from the 17th Through the 19th Century G. Graßhoff The History of Ptolemy's Star Catalogue A.W. Grootendorst Jan de Witt's Eiementa Curvarum Linearum, über Primus Continued after Index The Arithmetic of Infinitesimals John Wallis 1656 Translated from Latin to English with an Introduction by Jacqueline A. -

ED164303.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME -.. a ED 164.303 E 025. 458 AUTHOR Beck, A.; And Others ,TITLE Calculus, Part 3,'Studentl'Text, Unit No. 70. Revised Edition. , INSTITUTION Stanford Univ.,'CaliY. School Mathematics Study 't.-Group. SPONS AGENCY -National Science Foundation, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE ,65: NOTE 36bp.; For related documents, see SE 025 456-4:59; Contains light and braken'type EDRS PRICE MF-$0.83 HC-$19.41 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Calculus; *Cuiriculum; *Instructional Materials; *Mathematical Applications; Mathematics .Educatioi; S4Condary Education; *Secondary School Mathematics; *Textbooks IDENTIFIERS *School Mathematics Study Group ABSTRACT. This is part three of a'three-part SMSG calculuS text for high sahool students. One of the goals of the text is to present -calculus as a mathematical discipline -as yell, as presenting its practical uses. The authbrs emphasize the importance of being able to ipterpret the conceptS and theory interms of models to which they .apply. The text demonstrates the origins of the ideas of the calculus in pradtical problems; attempts to express these ideas precisely and_ ` develop them logically; and finally, returns to the problems and applies the theorems resulting from that development. Chapter topics include: (1)vectors and curves; (2) mechanics; (3) numerical analysis; (4) sequences and series; and (5) geometricl optics and waves. (MP) 1 - ********************************45*******************************/ * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can' be made ,* + ) - * from the original doCumente ../ * *****************************************************#*****,J U S DEPARTMENT lEDUCATIOPtilmi AI id NATIONALINS1 i I EDUCAT . THiSDOCUMENTHA! DUCEDEXACTLYAS TAE PERSONOR ORGAP ATIkr;T POINTSOF V STATEDDO NOT NECE SENTiOFFifiALNATION EDUCATIONPOSITION Calculus Part 3 Student's Text REVISED EDITION ' The following is a list of all thosewho.participiated in the preparation of this volume: A. -

Maharshi Dayanand University Rohtak Notice

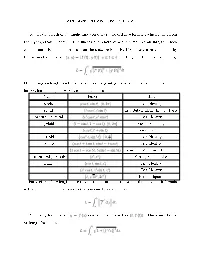

MAHARSHI DAYANAND UNIVERSITY ROHTAK (Established under Haryana Act No. XXV of 1975) ‘A+’ Grade University accredited by NAAC NOTICE FOR INVITING SUGGESTIONS/COMMENTS ON THE DRAFT SYLLABI OF B.A, B.SC., B.COM. UNDER CBCS Comments/suggestions are invited from all the stakeholders i.e Deans of the Faculties, HODs, Faculties and Principals of Affiliated Colleges on the Syllabi and Scheme of Examinations of B.A, B.Sc., B.Com. Programmes under CBCS (copy enclosed) through e-mail to the Dean, Academic Affairs upto 15.09.2020, so that the same may be incorporated in the final draft. Dean Academic Affairs B.A. Program Program Specific Objectives: i) To impart conceptual and theoretical knowledge of Mathematics and its various tools/techniques. ii) To equip with analytic and problem solving techniques to deal with the problems related to diversified fields. Program Specific Outcomes. Student would be able to: i) Acquire analytical and logical thinking through various mathematical tools and techniques and attain in-depth knowledge to pursue higher studies and ability to conduct research. ii) Achieve targets of successfully clearing various examinations/interviews for placements in teaching, banks, industries and various other organisations/services. B.A Pass Course under Choice Based Credit System Department of Mathematics Proposed Scheme of Examination SEMESTE COURSE OPTED COURSE NAME Credits Marks Internal Total Assessment Marks I Ability Enhancement (English/ Hindi/ MIL 4 80 20 100 Compulsory Course-I Communication)/ Environmental Science Core -

Arclength and Integrals

ARCLENGTH AND INTEGRALS To nd the length of a straight line, you can use the distance formula, which comes from the Pythagorean Theorem. But nding the length of a curve requires an integral which comes from a Riemann sum based on the distance formula. If you have a curve dened by the parametric equation (x; y) = (f (t) ; g (t)), a ≤ t ≤ b, the length of the curve is given by b q L = [f 0 (t)]2 + [g0 (t)]2dt: ˆa Calculating arclength leads to many interesting integrals which illustrate many dierent integration techniques. Here are some examples. Name Function Hint circle (cos t; sin t), [0; 2π] Trig Identity spiral (t cos t; t sin t) Trig Substitution, Int. by Parts logarithmic spiral (et cos t; et sin t) Trig Identity cycloid (t − sin t; 1 − cos t), [0; 2π] Power Reducing (cos t; t + sin t) Power Reducing astroid 3 3 , h π i Trig Identity cos t; sin t 0; 2 involute (cos t + t sin t; sin t − t cos t) Trig Identity (5 cos t − cos 5t; 5 sin t − sin 5t) Sum Identity, Power Reducing semicubical parabola (t2; t3) Factor, Substitution helix (cos t; sin t; t) Trig Identity (et cos t; et sin t; et) Trig Identity p t; 3t2; 2t3 Perfect Square For vectors of the length more than 2, the natural generalization of the arclength formula is the following, which applies to the previous three examples. b −!0 L = f (t) dt: ˆa A rectangular equation y = f (x) can be parametrized as (t; f (t)). -

The Rectification of Quadratures As a Central Foundational Problem for The

Historia Mathematica 39 (2012) 405–431 www.elsevier.com/locate/yhmat The rectification of quadratures as a central foundational problem for the early Leibnizian calculus Viktor Blåsjö Utrecht University, Postbus 80.010, 3508 TA Utrecht, The Netherlands Available online 2 August 2012 Abstract Transcendental curves posed a foundational challenge for the early calculus, as they demanded an extension of traditional notions of geometrical rigour and method. One of the main early responses to this challenge was to strive for the reduction of quadratures to rectifications. I analyse the arguments given to justify this enterprise and propose a hypothesis as to their underlying rationale. I then go on to argue that these foundational con- cerns provided the true motivation for much ostensibly applied work in this period, using Leibniz’s envelope paper of 1694 as a case study. Ó 2012 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Zusammenfassung Transzendentale Kurven stellten eine grundlegende Herausforderung für die frühen Infinitesimalkalkül dar, da sie eine Erweiterung der traditionellen Vorstellungen von geometrischen Strenge und Verfahren gefordert haben. Eines der wichtigsten frühen Antworten auf diese Herausforderung war ein Streben nach die Reduktion von Quadraturen zu Rektifikationen. Ich analysiere die Argumente die dieses Unternehmen gerechtfertigt haben und schlage eine Hypothese im Hinblick auf ihre grundlegenden Prinzipien vor. Ich behaupte weiter, dass diese grundlegenden Fragenkomplexe die wahre Motivation für viel scheinbar angewandte Arbeit in dieser Zeit waren, und benutze dafür Leibniz’ Enveloppeartikel von 1694 als Fallstudie. Ó 2012 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. MSC: 01A45 Keywords: Transcendental curves; Rectification of quadratures; Leibnizian calculus 1. Introduction In the early 1690s, when the Leibnizian calculus was in its infancy, a foundational problem long since forgotten was universally acknowledged to be of the greatest importance. -

Chapter 2 Parametric and Polar Curves

Chapter 2 Parametric and Polar Curves 2.1 Parametric Equations; Tangent Lines and Arc Length for Parametric Curves Parametric Equations So far we’ve described a curve by giving an equation that the coordinates of all points on the curve must satisfy. For example, we know that the equation y = x2 represents a parabola in rectangular coordinates. We now study another method for describing a curve in the plane. In this method, the x- and y-coordinates of points on the curve are given separately as functions of an additional variable t, called the parameter: x = f(t), y = g(t) These are called parametric equations for the curve. Each value of t determines a point (x, y), which we can plot in a coordinate plane. As t varies, the point (x, y)=(f(t),g(t)) varies and traces out a curve C, which we call a parametric curve. y C b (x, y) x Example 2.1 Sketch the curve defined by the parametric equations x = t2 3t, y = t 1 − − 14 MA112 (750001): Prepared by Asst.Prof.Dr. Archara Pacheenburawana 15 Solution For every value of t, we get a point on the curve. Here, we plot the points (x, y) determined by the values of t shown in the following table. y t x y -2 10 -3 t =5 b t =4 b -1 4 -2 t =3 b 0 0 -1 t =2 b 1 -2 0 b x 2 -2 1 t =1 b 3 0 2 t =0 b 4 4 3 t = 1 b − t = 2 5 10 4 − Notice that as t increases a particle whose position is given by the parametric equa- tions moves along the curve in the direction of the arrows. -

MTH 102 Calculus

Dr. Gizem SEYHAN ÖZTEPE Topic-5-Applications of Integration Arc Length, Area of a Surface of Revolution 1 What do we mean by the length of a curve? We might think of fitting a piece of string to the curve in Figure 1 and then measuring the string against a ruler. But that might be difficult to do with much accuracy if we have a complicated curve. If the curve is a polygon, we can easily find its length; we just add the lengths of the line segments that form the polygon. (We can use the distance formula to find the distance between the endpoints of each segment.) We are going to define the length of a general curve by first approximating it by a polygon and then taking a limit as the number of segments of the polygon is increased. This process is familiar for the case of a circle, where the circumference is the limit of lengths of inscribed polygons (see Figure 2). 2 Figure 3 3 4 Example 1 Find the length of the arc of the semicubical parabola 푦2 = 푥3 between the points (1,1) and (4,8). Solution 5 A surface of revolution is formed when a curve is rotated about a line. Such as a sphere, a cone, a cylinder … Let’s start with some simple surfaces. The lateral surface area of a circular cylinder with radius 푟 and height ℎ is taken to be 퐴 = 2휋푟ℎ because we can imagine cutting the cylinder and unrolling it (as in Figure 1) to obtain a rectangle with dimensions 2휋푟 and ℎ. -

The Parabola

Chapter 26 The parabola Let F be a given point and a given straight line on a plane. The locus of a variable point P at equal distances from F and is a parabola, with focus F and directrix . If we set up a coordinate system so that F =(a, 0) and is the line x = −a, then the parabola has equation y2 =4ax. Each point on the parabola has coordinates (at2, 2at) for some t.We shall simply call this “the point t of the parabola”. L P (at2, 2at) directrix −a O F =(a, 0) We collect some useful information on the parabola. (1) The line joining the points P (t1) and P (t2) has equation 2x − (t1 + t2)y +2at1t2 =0. This line passes through the focus F if and only if t1t2 = −1. 202 The parabola (2) Letting t1,t2 → t, we obtain the equation of the tangent at t: x − ty + at2 =0. 1 (− 2 0) It has slope t and intersects the axis of the parabola at at , . (3) The normal at t is the line perpendicular to the tangent at t. It has equation tx + y = at3 +2at. (4) Construction of tangent and normal at t: the circle, center F , passing through t, intersects the axis of the parabola at two points. One of these is on the tangent, and the other on the normal. t O F (5) The area of the triangle with vertices t1, t2, t3 on the parabola is 2 2 1 1 at1 at1 2 2 at2 2at2 1 = −a (t1 − t2)(t2 − t3)(t3 − t1). -

On Evolute Cusps and Skeleton Bifurcations Alexander Belyaev And

On Evolute Cusps and Skeleton Bifurcations Alexander Belyaev and Shin Yoshizawa The University of Aizu Aizu-Wakamatsu 965-8580 Japan g fbelyaev, m5031126 @u-aizu.ac.jp Abstract Fig. 2 demonstrates the description of the skeleton of a figure as the set of centers of maximal disks inscribed in the Consider a 2D smooth closed curve evolving in time, the figure. skeleton (medial axis) of the figure bounded by the curve, and the evolute of the curve. A new branch of the skeleton can appear / disappear when an evolute cusp intersects the skeleton. In this paper, we describe exact conditions of the skeleton bifurcations corresponding to such intersections. Similar results are also obtained for 3D surfaces evolving in time. Figure 2. Left: a \bison" gure, its skeleton, and a maximal disk inscrib ed in the gure; the b old tisapoint of tangency b etw een the disk and Introduction poin the b oundary of the gure. Right: the skeleton of a gure can b e de ned as the set of centers of The skeleton or medial axis of a planar figure is the clo- maximal disks inscrib ed in the gure. sure of the set of centers of maximal disks contained inside the figure, i.e., those discs contained in the figure but in no other disc in the figure. The skeleton is an important shape Consider a figure evolving in time. How does the skele- descriptor invented by Blum [6]. It is extensively used in ton of the figure change? An analytical description of how connection with human shape perception theories [5], [9]. -

C H a P T E R 1 0 Conics, Parametric Equations, and Polar Coordinates

CHAPTER 10 Conics, Parametric Equations, and Polar Coordinates Section 10.1 Conics and Calculus . 360 Section 10.2 Plane Curves and Parametric Equations . 383 Section 10.3 Parametric Equations and Calculus . 392 Section 10.4 Polar Coordinates and Polar Graphs . 407 Section 10.5 Area and Arc Length in Polar Coordinates . 423 Section 10.6 Polar Equations of Conics and Kepler’s Laws . 436 Review Exercises . 444 Problem Solving . 461 CHAPTER 10 Conics, Parametric Equations, and Polar Coordinates Section 10.1 Conics and Calculus 1. y2 ϭ 4x 2. x2 ϭ 8y 3. ͑x ϩ 3͒2 ϭϪ2͑y Ϫ 2͒ Vertex: ͑0, 0͒ Vertex: ͑0, 0͒ Vertex: ͑Ϫ3, 2͒ ϭ ϭ ϭϪ1 p 1 > 0 p 2 > 0 p 2 < 0 Opens to the right Opens upward Opens downward Matches graph (h). Matches graph (a). Matches graph (e). ͑x Ϫ 2͒2 ͑y ϩ 1͒2 x2 y2 x2 y2 4. ϩ ϭ 1 5. ϩ ϭ 1 6. ϩ ϭ 1 16 4 9 4 9 9 Center: ͑2, Ϫ1͒ Center: ͑0, 0͒ Circle radius 3. Ellipse Ellipse Matches (g) Matches (b) Matches (f) y2 x2 ͑x Ϫ 2͒2 y2 7. Ϫ ϭ 1 8. Ϫ ϭ 1 16 1 9 4 Hyperbola Hyperbola Center: ͑0, 0͒ Center: ͑Ϫ2, 0͒ Vertical transverse axis Horizontal transverse axis Matches (c) Matches (d) 2 ϭϪ ϭ ͑Ϫ3͒ 2 ϩ ϭ 9. y 6x 4 2 x 10. x 8y 0 Vertex: ͑0, 0͒ y x2 ϭ 4͑Ϫ2͒y y 3 8 Focus: ͑Ϫ , 0͒ (0, 0) 2 Vertex: ͑0, 0͒ x 3 −8 −4 4 8 ϭ 4 Directrix: x 2 ͑ Ϫ ͒ Focus: 0, 2 − (0, 0) 4 x ϭ 12 8 4 Directrix: y 2 −8 4 −12 8 11.