Power, Property, Publicity and Democracy in Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

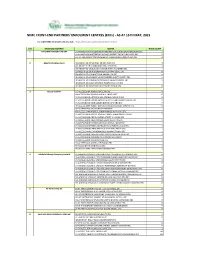

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (Ercs) - AS at 15TH MAY, 2021

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (ERCs) - AS AT 15TH MAY, 2021 For other NIMC enrolment centres, visit: https://nimc.gov.ng/nimc-enrolment-centres/ S/N FRONTEND PARTNER CENTER NODE COUNT 1 AA & MM MASTER FLAG ENT LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGBABIAKA STR ILOGBO EREMI BADAGRY ERC 1 LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGUMO MARKET OKOAFO BADAGRY ERC 0 OG-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG BAALE COMPOUND KOFEDOTI LGA ERC 0 2 Abuchi Ed.Ogbuju & Co AB-ABUCHI-ED ST MICHAEL RD ABA ABIA ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED BUILDING MATERIAL OGIDI ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED OGBUJU ZIK AVENUE AWKA ANAMBRA ERC 1 EB-ABUCHI-ED ENUGU BABAKALIKI EXP WAY ISIEKE ERC 0 EN-ABUCHI-ED UDUMA TOWN ANINRI LGA ERC 0 IM-ABUCHI-ED MBAKWE SQUARE ISIOKPO IDEATO NORTH ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AFOR OBOHIA RD AHIAZU MBAISE ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AMAIFEKE TOWN ORLU LGA ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UMUNEKE NGOR NGOR OKPALA ERC 0 3 Access Bank Plc DT-ACCESS BANK WARRI SAPELE RD ERC 0 EN-ACCESS BANK GARDEN AVENUE ENUGU ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA WUSE II ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK LADOKE AKINTOLA BOULEVARD GARKI II ABUJA ERC 1 FC-ACCESS BANK MOHAMMED BUHARI WAY CBD ERC 0 IM-ACCESS BANK WAAST AVENUE IKENEGBU LAYOUT OWERRI ERC 0 KD-ACCESS BANK KACHIA RD KADUNA ERC 1 KN-ACCESS BANK MURTALA MOHAMMED WAY KANO ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ACCESS TOWERS PRINCE ALABA ONIRU STR ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADEOLA ODEKU STREET VI LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA STR VI ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK IKOTUN JUNCTION IKOTUN LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ITIRE LAWANSON RD SURULERE LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK LAGOS ABEOKUTA EXP WAY AGEGE ERC 1 LA-ACCESS -

Domain Without Subjects Traditional Rulers in Post-Colonial Africa

Taiwan Journal of Democracy, Volume 13, No. 2: 31-54 Domain without Subjects Traditional Rulers in Post-Colonial Africa Oscar Edoror Ubhenin Abstract The domain of traditional rulers in pre-colonial Africa was the state, defined by either centralization or fragmentation. The course of traditional rulers in Africa was altered by colonialism, thereby shifting their prerogative to the nonstate domain. Their return in post-colonial Africa has coincided with their quest for constitutional “space of power.” In effect, traditional rulers are excluded from modern state governance and economic development. They have remained without subjects in post-colonial Africa. Thus, the fundamental question: How and why did traditional rulers in post-colonial Africa lose their grip over their subjects? In explaining the loss of traditional rulers’ grip over subjects in their domains, this essay refers to oral tradition and published literature, including official government documents. Empirical evidence is drawn from Nigeria and other parts of Africa. Keywords: African politics, chiefs and kings, post-colonialism, traditional domain. During the era of pre-colonialism, African chiefs and kings (also called traditional rulers) operated in the domain of the state, characterized by either centralization or fragmentation. This characterization refers to the variations in political cum administrative institutions along the lines of several hundred ethnic groups that populated Africa. “Centralized” or “fragmented” ethnic groups were based on the number of levels of jurisdiction that transcended the local community, “where more jurisdictional levels correspond[ed] to more centralized groups.”1 Traditional rulers in Africa had mechanisms for formulating public policies and engaging public officers who assisted them in development and delivering relevant services to their subjects. -

Nigeria's Nascent Democracy

An International Multi-Disciplinary Journal, Ethiopia Vol. 5 (2), Serial No. 19, April, 2011 ISSN 1994-9057 (Print) ISSN 2070-0083 (Online) Nigeria’s Nascent Democracy and ‘WAR’ Against Corruption: A Rear View Mirror (56-71) Ojo, Emmanuel O. - University of Ilorin, P.M.B. 1515, Ilorin, Kwara State, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected] Cell: +2348033822383; 07057807714 Home: 022-008330 Abstract One of the problems facing the nascent democracy in Nigeria which is more pressing than economic development is the high rate of brazen corruption in virtually all facets of the polity’s national life. Thus, the thrust of this paper is a review of the recent ‘WAR’ against corruption in Nigeria. The paper surveys a number of manifestations of corruption in the body politik and the country’s woes. The paper however infers that unless the institutional mechanisms put in place are rejuvenated coupled with political will on the part of the political actors, the so-called war may be a mirage after all. Key words: Corruption, Kleptocracy, Constitutionalism, Integrity, Poverty. Introduction Most of us came into the National Assembly with very high expectations...when we go around campaigning and asking for votes, we don’t get these votes free. You spend some money. Most of us even sold houses. You come in through legitimate means but you can’t recoup what you spent (The News , April 4, 2005:50). Copyright © IAARR 2011: www.afrrevjo.com 56 Indexed African Journals Online: www.ajol.info Vol. 5 (2), Serial No. 19, April, 2011. Pp. 56-71 The above quotation by a one time Senate President – Adolphus Wabara – betrayed what psychologists would call a Freudian slip. -

The 9Th Toyin Falola Annual International Conference on Africa and the African Diaspora (Tofac 2019)

The 9th Toyin Falola Annual International Conference On Africa And The African Diaspora (tofac 2019) THEME: RELIGION, THE STATE AND GLOBAL POLITICS JULY 1-3, 2019 @BABCOCK UNIVERSITY ILISHAN-REMO, OGUN STATE, NIGERIA PROGRAMME OF EVENTS FEATURING: DISTINGUISHED GUEST OF HONOUR CHIEF DR OLUSEGUN OBASANJO, GCFR, PhD Former President, Federal Republic of Nigeria CHIEF HOST PROFESSOR ADEMOLA S. TAYO HOST President/Vice-Chancellor, Babcock PROFESSOR ADEMOLA DASYLVA University Board Chair, TOFAC (International) GRAND HOST HE CHIEF DR DAPO ABIODUN, MFR Executive Governor, Ogun State, Nigeria CONFERENCE KEYNOTE SPEAKERS HE Bishop Matthew Hassan Kukah, Bishop of the Catholic Diocese of Sokoto, Nigeria Professor Bankole Omotoso, Writer, Dean, Faculty of Humanities, Elizade University Professor Ibigbolade Aderibigbe, Professor of Religion & Associate Director, The African Studies Institute, University of Georgia, Athens, USA BANQUET CHAIRMAN: His Imperial Majesty Fuankem Achankeng I, MA, MA, PhD The Nyatema of Atoabechied Ruler, Atoabechied, Lebialem Southwestern Cameroon & Professor, University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh, USA BANQUET SPECIAL GUEST OF HONOUR Professor Jide Owoeye Chairman, Governing Council & Proprietor Lead City University, Ibadan 2 NATIONAL ANTHEM Great lofty heights attain To build a nation where peace Arise, O compatriot, And justice shall reign. Nigeria’s call obey To serve our father’s land BABCOCK UNIVERSITY With love and strength and faith The labour of our heroes past ANTHEM Shall never be in vain Hail Babcock God’s own University To serve with heart and mind Built on the power of His Word One nation bound in freedom Knowledge and truth, Peace and unity Service to God and man Building a future for the youth Wholistic education, O God of creation, The vision is still aflame: Direct our noble cause Mental, physical, social, spiritual Guide our leaders right Babcock is it! Help our youths the truth to know Hail, Babcock God’s own University In love and honesty to grow Good life here and forever more. -

NIGERIA COUNTRY of ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service

NIGERIA COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service 6 January 2012 NIGERIA 6 JANUARY 2012 Contents Preface Latest news EVENTS IN NIGERIA FROM 16 DECEMBER 2011 TO 3 JANUARY 2012 Useful news sources for further information REPORTS ON NIGERIA PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED AFTER 15 DECEMBER 2011 Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................ 1.01 Map ........................................................................................................................ 1.07 2. ECONOMY ................................................................................................................ 2.01 3. HISTORY (1960 – 2011) ........................................................................................... 3.01 Independence (1960) – 2010 ................................................................................ 3.02 Late 2010 to February 2011 ................................................................................. 3.04 4. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS (MARCH 2011 TO NOVEMBER 2011) ...................................... 4.01 Elections: April, 2011 ....................................................................................... 4.01 Inter-communal violence in the middle belt of Nigeria ................................. 4.08 Boko Haram ...................................................................................................... 4.14 Human rights in the Niger Delta ......................................................................... -

Statistical Report on Women and Men in Nigeria

2018 STATISTICAL REPORT ON WOMEN AND MEN IN NIGERIA NATIONAL BUREAU OF STATISTICS MAY 2019 i TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................ ii PREFACE ...................................................................................................................................... vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................ ix LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................... xiii LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................... xv LIST OF ACRONYMS................................................................................................................ xvi CHAPTER 1: POPULATION ....................................................................................................... 1 Key Findings ................................................................................................................................ 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 1 A. General Population Patterns ................................................................................................ 1 1. Population and Growth Rate ............................................................................................ -

The Digital Dilemma 2 Perspectives from Independent Filmmakers, Documentarians and Nonprofi T Audiovisual Archives

Copyright ©2012 Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. “Oscar,” “Academy Award,” and the Oscar statuette are registered trademarks, and the Oscar statuette the copyrighted property, of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. The accuracy, completeness, and adequacy of the content herein are not guaranteed, and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences expressly disclaims all warranties, including warranties of merchantability, fi tness for a particular purpose and non-infringement. Any legal information contained herein is not legal advice, and is not a substitute for advice of an attorney. All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this document may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the publisher. Published by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Inquiries should be addressed to: Science and Technology Council Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences 1313 Vine Street, Hollywood, CA 90028 (310) 247-3000 http://www.oscars.org Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Digital Dilemma 2 Perspectives from Independent Filmmakers, Documentarians and Nonprofi t Audiovisual Archives 1. Digital preservation – Case Studies. 2. Film Archives – Technological Innovations 3. Independent Filmmakers 4. Documentary Films 5. Audiovisual I. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and -

The Media and the Militants: Constructing the Niger Delta Crisis

THE MEDIA AND THE MILITANTS THE MEDIA AND THE MILITANTS: CONSTRUCTING THE NIGER DELTA CRISIS by Innocent Chiluwa This study applies Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) and Corpus Linguistics methods to analyse the frequently used lexical items by the Nigerian press to represent the Niger Delta militia groups and their activities. The study shows that the choice of particular vocabulary over other available options reveals value judgements that reflect power, identity and socio-economic marginalization. Concordances and collocational tools are used to provide semantic profiles of the selected lexical items and collocational differences are highlighted. A list of collocates was obtained from the concordances of the 'Nigerian Media Corpus' (NMC) (a corpus of 500,000 words compiled by the author). The study reveals that the negative representations of the ethnic militia are an ideological strategy used to shift attention from the real issues of ethnic marginalization and exploitation of the Niger Delta – a region solely responsible for Nigeria's oil-based economy. Arguably, the over-publicised security challenges in the Niger Delta succeed in creating suspicion and apprehension among the citizenry, whereas the government, which receives abundant revenue from oil, does little to develop the entire country. Keywords: Nigeria, ethnic militants, Niger Delta, corpus linguistics, ideology, the press 1. Introduction The conflict in the Niger Delta (ND) of Nigeria has often been attributed to Nigeria's federal structure that groups the country into unequal regions. The north and the west and some parts of the eastern region are the 'majority' ethnic groups with full political and demographic privileges. These groups are said to dominate the 'minority' ethnic groups such as those populating the Delta region. -

Joint Admissions and Matriculation Board

JOINT ADMISSIONS AND MATRICULATION BOARD APPLICATION STATISTICS BY INTITUTION AND GENDER (AGE LESS THAN 16) S/NO INSTITUTION F M TOTAL 1 ABUBAKAR TAFAWA BALEWA UNIVERSITY, BAUCHI, BAUCHI STATE 78 89 167 2 ACHIEVERS UNIVERSITY, OWO, ONDO STATE 3 0 3 3 ADAMAWA STATE UNIVERSITY, MUBI, ADAMAWA STATE 8 5 13 4 ADEKUNLE AJASIN UNIVERSITY, AKUNGBA-AKOKO, ONDO STATE 169 68 237 5 ADELEKE UNIVERSITY, EDE, OSUN STATE 6 4 10 6 ADEYEMI COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, ONDO STATE. (AFFL TO OAU, ILE-IFE) 8 4 12 7 ADEYEMI COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, ONDO, ONDO STATE 1 0 1 8 AFE BABALOLA UNIVERSITY, ADO-EKITI, EKITI STATE 92 71 163 9 AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY TEACHING HOSPITAL, ZARIA, KADUNA STATE 2 0 2 10 AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA, KADUNA STATE 826 483 1309 11 AIR FORCE INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, KADUNA, KADUNA STATE 2 1 3 12 AJAYI CROWTHER UNIVERSITY, OYO, OYO STATE 6 1 7 13 AKANU IBIAM FEDERAL POLYTECHNIC, UNWANA, AFIKPO, EBONYI STATE 5 3 8 14 AKWA IBOM STATE UNIVERSITY, IKOT-AKPADEN, AKWA IBOM STATE 39 28 67 15 AKWA-IBOM STATE POLYTECHNIC, IKOT-OSURUA, AKWA IBOM STATE 7 3 10 16 ALEX EKWUEME FEDERAL UNIVERSITY, NDUFU-ALIKE, EBONYI STATE 55 33 88 17 AL-HIKMAH UNIVERSITY, ILORIN, KWARA STATE 3 1 4 18 AL-QALAM UNIVERSITY, KATSINA, KATSINA STATE 6 1 7 19 ALVAN IKOKU COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, IMO STATE, (AFFL TO UNIV OF NIGERA, NSUKKA) 3 1 4 20 AMBROSE ALLI UNIVERSITY, EKPOMA, EDO STATE 208 117 325 21 AMERICAN UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, YOLA, ADAMAWA STATE 4 8 12 22 AMINU DABO COLLEGE OF HEALTH SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, KANO, KANO STATE 1 0 1 23 ANCHOR UNIVERSITY, AYOBO, LAGOS STATE -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE A. PERSONAL i. Name: ADEBAYO Yetunde Olufunmilola (Nee Ayanbadejo) ii. Date of Birth: 8th July, 1978 iii. Place of Birth: Ijebu-Ode iv. Age: 41years v. Sex: Female vi. Marital Status: Widow vii. Nationality: Nigerian viii. Town and State of Origin: Ijebu-Ode/Ogun State ix. Contact Address: Department of Nutrition and Dietetics, College of Food Science and Human Ecology, Federal University of Agriculture, P.M.B. 2240 Abeokuta. x. Phone Number: +234-80-28-169-320; +234-81-31-303-949 xi. E-mail Address: [email protected] [email protected] xii. Present Post and Salary: Lecturer II CONUASS 03/01 B. EDUCATIONAL BACKGROUND (i) Educational Institutions Attended with dates Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta, Ogun State 2008-2019 University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Oyo State 2007-2009 University of Agriculture, Abeokuta, Ogun State 2003-2005 University of Agriculture, Abeokuta, Ogun State 1998-2001 Ogun State Polytechnic, Ojere, Abeokuta, Ogun State 1996-1998 Adeola Odutola College, Ijebu-Ode Ogun State 1999 Ogbogbo Baptist Grammar School, Ijebu-Ode 1995 (ii) Academic and Professional Qualifications (with dates) Ph.D. (Nutrition and Dietetics) 2019 Test of Professional Competence TOPC 2015 (Institute for Dietetics in Nigeria - IDN) Post Graduate Diploma in Education 2009 M.Sc. (Nutrition and Dietetics) 2005 B.Sc. (Nutrition and Dietetics) 2001 ND (Food Science and Technology) 1998 Senior Secondary School Certificate 1999 1 C. WORK EXPERIENCE WITH DATE Work Experience in the University System August 2019 till date Federal University of Agriculture P. M. B. 2240 Abeokuta, Ogun State. Lecturer II (Nutrition & Dietetics Dept.) Current Job Description Lecturer II - Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta, Ogun State. -

Nigerian Newspaper Ownership in a Changing Polity

African Study Monographs, 32 (4): 177-203, October 2011 177 WHEN (NOT) TO BE A PROPRIETOR: NIGERIAN NEWSPAPER OWNERSHIP IN A CHANGING POLITY A.O. ADESOJI Department of Historyy, Obafemi Awolowo University H.P. HAHN Institut für Ethnologie, Johann Wolfgang Göthe Universität ABSTRACT The Nigerian press has seen different kinds of ownership ranging from missions, groups, and individuals to governments. Yet ownership of some newspapers remained obscure and a subject of speculation. Beyond the traditional functions, Nigerian newspapers have served purposes that diverged from their professed philosophy or ideologies. Despite travails particularly during the long military rule, and the seeming unprofi tability of most ventures, newspapers have continued to proliferate. Ownership is central to the functionality, style, outlook, survival and perception of newspapers. These issues raise some fundamental questi- ons as to why various parties venture into newspaper ownership, or desire to retain ownership when it is risky or economically unwise to do so. Using historical analysis approaches, the authors argue that the glamour and self-fulfi lment in newspaper proprietorship as well as the parochial interest which some newspapers have served allure their owners and even encourage the addition of new titles even when other dynamics point to the contrary. Key Words: Newspapers; Ownership; Proliferation; Politics; Profi tability; Nation-Building; Historical Analysis. INTRODUCTION The press remains an important institution all over the world. Its centrality to communication is not in doubt (Lazarfeld & Merton, 1971: 554–578; Mueller, 1976; Rubin, 1997: 104–106). In the performance of its public watchdog role, the press serves as a behavioural regulatory agent on the activities of government and its functionaries (Kolawole, 1998). -

African Continental Qualifications Framework MAPPING STUDY

African Continental Qualifications Framework MAPPING STUDY Country Report Working Paper NIGERIA SIFA Skills for Youth Employability Programme Author: Jacinta Ezeahurukwe Reviewer: Eduarda Castel-Branco (European Training Foundation - ETF) December 2020 This working paper on the National Qualifications Framework of Nigeria is part of the Mapping Study of qualifications frameworks in Africa, elaborated in 2020 in the context of the project AU EU Skills for Youth Employability: SIFA Technical Cooperation – Developing the African Continental Qualifications Framework (ACQF). The reports of this collection are: • Reports on countries' qualifications frameworks: Angola, Cape Verde, Cameroon, Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, Ivory Coast, Morocco, Mozambique, Nigeria, Senegal, South Africa and Togo • Reports on qualifications frameworks of Regional Economic Communities: East African Community (EAC), Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), Southern African Development Community (SADC) Authors of the reports: • Eduarda Castel-Branco (ETF): reports Angola, Cape Verde, Cameroon, Morocco, Mozambique • James Keevy (JET Education Services): report Ethiopia • Jean Adotevi (JET Education Services): reports Senegal, Togo and ECOWAS • Lee Sutherland (JET Education Services): report Egypt • Lomthie Mavimbela (JET Education Services): report SADC • Maria Overeem (JET Education Services): report Kenya and EAC • Raymond Matlala (JET Education Services): report South Africa • Teboho Makhoabenyane (JET Education Services): report South Africa • Tolika Sibiya