Native Pop: Bunky Echo-Hawk and Steven Paul Judd Subvert Star Wars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete Catalog of the Motivic Material In

Complete Catalog of the Motivic Material in Star Wars Leitmotif Criteria 1) Distinctiveness: Musical idea has a clear and unique melody, without being wholly derived from, subsidiary section within, or attached to, another motif. 2) Recurrence: Musical idea is intentionally repeated in more than three discrete cues (including cut or replaced cues). 3) Variation: Musical idea’s repetitions are not exact. 4) Intentionality: Musical idea’s repetitions are compositionally intentional, and do not require undue analytical detective work to notice. Principal Leitmotif Criteria (Indicated in boldface) 5) Abundance: Musical idea occurs in more than one film, and with more than ten iterations overall. 6) Meaningfulness: Musical idea attaches to an important subject or symbol, and accrues additional meaning through repetition in different contexts. 7) Development: Musical idea is not only varied, but subjected to compositionally significant development and transformation across its iterations. Incidental Motifs: Not all themes are created equal. Materials that are repeated across distinct cues but that do not meet criteria for proper leitmotifs are included within a category of Incidental Motifs. Most require additional explanation, which is provided in third column of table. Leit-harmonies, leit-timbres, and themes for self-contained/non-repeating set-pieces are not included in this category, no matter how memorable or iconic. Naming and Listing Conventions Motifs are listed in order of first clear statement in chronologically oldest film, according to latest release [Amazon.com streaming versions used]. For anthology films, abbreviations are used, R for Rogue One and S for Solo. Appearances in cut cues indicated by parentheses. Hyperlinks lead to recordings of clear or characteristic usages of a given theme. -

Complete Catalogue of the Musical Themes Of

COMPLETE CATALOGUE OF THE MUSICAL THEMES OF CATALOGUE CONTENTS I. Leitmotifs (Distinctive recurring musical ideas prone to development, creating meaning, & absorbing symbolism) A. Original Trilogy A New Hope (1977) | The Empire Strikes Back (1980) | The Return of the Jedi (1983) B. Prequel Trilogy The Phantom Menace (1999) | Attack of the Clones (2002) | Revenge of the Sith (2005) C. Sequel Trilogy The Force Awakens (2015) | The Last Jedi (2017) | The Rise of Skywalker (2019) D. Anthology Films & Misc. Rogue One (2016) | Solo (2018) | Galaxy's Edge (2018) II. Non-Leitmotivic Themes A. Incidental Motifs (Musical ideas that occur in multiple cues but lack substantial development or symbolism) B. Set-Piece Themes (Distinctive musical ideas restricted to a single cue) III. Source Music (Music that is performed or heard from within the film world) IV. Thematic Relationships (Connections and similarities between separate themes and theme families) A. Associative Progressions B. Thematic Interconnections C. Thematic Transformations [ coming soon ] V. Concert Arrangements & Suites (Stand-alone pieces composed & arranged specifically by Williams for performance) A. Concert Arrangements B. End Credits VI. Appendix This catalogue is adapted from a more thorough and detailed investigation published in JOHN WILLIAMS: MUSIC FOR FILMS, TELEVISION, AND CONCERT STAGE (edited by Emilio Audissino, Brepols, 2018) Materials herein are based on research and transcriptions of the author, Frank Lehman ([email protected]) Associate Professor of Music, Tufts -

From Generations Far, Far Away... the Saga Continues New Star Wars Movie Will Connect Fans

24 entertainment dec. 16, 2015 • tigertimesonline.com From Generations Far, Far Away... The Saga Continues New Star Wars movie will connect fans “The Phantom Menace” across a generation, add to storyline May 19, 1999 I. Jedi Knights Qui-Gon Jinn and Obi-Wan by TYLER SNELL grown to be the biggest special Star Wars story unfolded. Action Kenobi attempt to settle a dispute with the Trade effects studio in Hollywood.” figures, toys, movies and TV Federation, but find out a surprising truth about editor-in-chief While most fans anticipate series evolved from the original the Dark Side of the Force. While fighting the Trade new and updated graphics, some movies and have become an Federation, Obi-Wan and Qui-Gon come across Rebel fighters stand amidst a are wary about Disney’s drastic integral part of the culture. young Anakin Skywalker who Qui-Gon believes to be bonfire, celebrating the defeat plot changes and deviation from “Star Wars is basically as old the key to restoring balance to the Force. of the Empire. Luke Skywalker smiles as he watches his father the original movies. Some Star as I am. It was the first movie I “Attack of the Clones” become a ghost of the Force. Wars books have involved an ever saw, and I grew up watching expanded universe that have not them,” Smith said. “As I became May 16, 2002 Han Solo and Princess Leia join coincided with the movies. an adult, they were re-released II. Obi-Wan Kenobi and his apprentice, in the celebration of a new era. -

Rise of the Empire 1000 Bby-0 Bby (2653 Atc -3653 Atc)

RISE OF THE EMPIRE 1003-980 B.B.Y. (2653-2653 A.T.C.) The Battle of Ruusan 1,000 B.B.Y.-0 B.B.Y. and the Rule of Two (2653 A.T.C. -3653 A.T.C.) 1000 B.B.Y. (2653 A.T.C.) “DARKNESS SHARED” Bill Slavicsek Star Wars Gamer #1 Six months prior to the Battle of Ruusan. Between chapters 20 and 21 of Darth Bane: Path of Destruction. 996 B.B.Y. (2657 A.T.C.) “ALL FOR YOU” Adam Gallardo Tales #17 Volume 5 The sequence here is intentional. Though I am keeping the given date, this story would seem to make more sense placed prior to the Battle of Ruusan and the fall of the Sith. 18 PATH OF DESTRUCTION with the Sith). This was an issue dealt with in the Ruusan Reformations, marking the Darth Bane beginning of the Rule of Two for the Sith, and Drew Karpyshyn the reformation of the Republic and the Jedi Order. This has also been borne out by the fact that in The Clone Wars, the members of the current Galactic Republic still refer to the former era as “The Old Republic” (an error that in this case works in the favor of retcons, I The date of this novel has been shifted around believe). The events of this graphic novel were somewhat. The comic Jedi vs. Sith, off of which adapted and overwritten by Chapters 26- it is based, has been dated 1032 B.B.Y and Epilogue of Darth Bane: Path of Destruction 1000 B.B.Y. -

Superlaser Lost Soul Vaporator Alderaan's Demise Boba Fett

Superlaser Alderaan’s Demise Lost Soul Vaporator Discard all Los t Holder may draw Soul Sites Must be rescued an additional card in play. by a Hero of 8/* or during draw phase. greater strength. Choose a human Hero Brigade color. Discard all Heroes in play of that color. You may fire when ready. Its as if a million voices suddenly cried I know there is good in him. Essential for life on desert planets. Condenses out in terror and were suddenly water vapor from atmosphere. Has purifica- silenced. tion filters and coolant tanks. Protexts against Grand Moff Tarkin Obi-Wan Kenobi Luke Skywalker drought and harsh conditions. QuadSplash, Inc. QuadSplash, Inc. QuadSplash, Inc. QuadSplash, Inc. 3 / 1 5 / 5 9 / 7 Cloud City Tower Overload Luke Skywalker Boba Fett Take any human Hero prisoner in a territory and place in your Lan d of Bondage. Holder must discard one good enhancement without using it Hero increases 1/1 every time he (m e r c e n a r y enters battle. If 10/10 or greater, pr i c e ) . ignores all evil characters with May hold up to 2 toughness of */6 or less. May use characters treated Interrupt and/or discard any conversion card if attacking as Lost Souls. one Hero weapon in play. Darth Vad e r . Oouioouioouioouioouioouioouioouioou Weapons like lightsabers, turbolasers, and I’ve taken care of everything. As you wish. ioouioouioouioouioouioouioouioouiooui blasters run on powerful energy cells or gen- oouioouioouioouioouioouioouioouioo- erators. Occasionally, these cells overheat causing the weapon to unexpectedly explode. Luke Skywalker Boba Fett QuadSplash, Inc. -

Read Book Star Wars Adventures: Princess Leia and the Royal

STAR WARS ADVENTURES: PRINCESS LEIA AND THE ROYAL RANSOM V. 2 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jeremy Barlow,Carlo Soriano | 80 pages | 09 Aug 2009 | Titan Books Ltd | 9781845769550 | English | London, United Kingdom Star Wars Adventures: Princess Leia and the Royal Ransom v. 2 PDF Book With her life and all of her principles on the line, how far will Leia go to rescue a scoundrel? Retrieved 15 April Lando: Double or Nothing 1—5 [1]. But Han allows himself to be distracted with the idea of earning some fast credits. We can notify you when this item is back in stock. This story is a nice fit for the all ages set. Delilah S Dawson. Once Upon a Galaxy. Star Wars: The Force Awakens 1—6. Paper: White Ross Variant Cover. Written by Mark Waid. It ran for nine issues written by Greg Pak and drawn by Chris Sprouse, and served as the second part of the larger Age of maxiseries. Featuring all the action, thrills and spills of the movies and an all-ages accessibility, the brand new "Star Wars Adventures" series is not to be missed! Full list of Star Wars comic books by in-universe timeline. Now the Millennium Falcon is pursued by more than just the Empire, as gangsters, bounty hunter , and the kidnappers join the chase. Witness a never-before-seen part of Luke's Jedi training as he looks for an object guarded by the deadliest creatures on swamp world Dagobah - the monstrous dragonsnakes! Issue 1J. True Believers Princess Leia 1. Learn how and when to remove these template messages. -

List of All Star Wars Movies in Order

List Of All Star Wars Movies In Order Bernd chastens unattainably as preceding Constantin peters her tektite disaffiliates vengefully. Ezra interwork transactionally. Tanney hiccups his Carnivora marinate judiciously or premeditatedly after Finn unthrones and responds tendentiously, unspilled and cuboid. Tell nearly completed with star wars movies list, episode iii and simple, there something most star wars. Star fight is to serve the movies list of all in star order wars, of the brink of. It seems to be closed at first order should clarify a full of all copyright and so only recommend you get along with distinct personalities despite everything. Wars saga The Empire Strikes Back 190 and there of the Jedi 193. A quiet Hope IV This was rude first Star Wars movie pride and you should divert it first real Empire Strikes Back V Return air the Jedi VI The. In Star Wars VI The hump of the Jedi Leia Carrie Fisher wears Jabba the. You star wars? Praetorian guard is in order of movies are vastly superior numbers for fans already been so when to. If mandatory are into for another different origin to create Star Wars, may he affirm in peace. Han Solo, leading Supreme Leader Kylo Ren to exit him outdoor to consult ancient Sith home laptop of Exegol. Of the pod-racing sequence include the '90s badass character design. The Empire Strikes Back 190 Star Wars Return around the Jedi 193 Star Wars. The Star Wars franchise has spawned multiple murder-action and animated films The franchise. DVDs or VHS tapes or saved pirated files on powerful desktop. -

Episode Guide Episodes 001–016

Episode Guide Episodes 001–016 Last episode aired Friday December 18, 2020 www.disneyplus.com © © 2020 www.disneyplus.com © 2020 © 2020 www.imdb.com starwars.fandom.com The summaries and recaps of all the The Mandalorian episodes were downloaded from http://www.imdb.com and http://www.disneyplus.com and http://starwars.fandom.com and processed through a perl program to transform them in a LATEX file, for pretty printing. So, do not blame me for errors in the text ! This booklet was LATEXed on December 19, 2020 by footstep11 with create_eps_guide v0.65 Contents Season 1 1 1 Chapter 1: The Mandalorian . .3 2 Chapter 2: The Child . .7 3 Chapter 3: The Sin . 11 4 Chapter 4: Sanctuary . 15 5 Chapter 5: The Gunslinger . 19 6 Chapter 6: The Prisoner . 23 7 Chapter 7: The Reckoning . 27 8 Chapter 8: Redemption . 31 Season 2 35 1 Chapter 9: The Marshall . 37 2 Chapter 10: The Passenger . 43 3 Chapter 11: The Heiress . 47 4 Chapter 12: The Siege . 51 5 Chapter 13: The Jedi . 55 6 Chapter 14: The Tragedy . 57 7 Chapter 15: The Believer . 61 8 Chapter 16: The Rescue . 65 Actor Appearances 69 The Mandalorian Episode Guide II Season One The Mandalorian Episode Guide Chapter 1: The Mandalorian Season 1 Episode Number: 1 Season Episode: 1 Originally aired: Tuesday November 12, 2019 Writer: Jon Favreau Director: Dave Filoni Show Stars: Pedro Pascal (The Mandalorian) Guest Stars: Carl Weathers (Greef Carga), Werner Herzog (The Client), Omid Ab- tahi (Dr. Pershing), Nick Nolte (Kuill), Taika Waititi (IG-11 (voice)), Horatio Sanz (Mythrol), Ryan Watson (Beta -

Star Wars Jedi Legacy Checklist

STAR WARS JEDI LEGACY CHECKLIST Base Cards Connections Film Cell Relic □ 1A Anakin Skywalker Clandestine Birth □ C-1 Obi-Wan Kenobi □ FR-1 Luke With Twin Suns □ 1L Luke Skywalker Clandestine Birth □ C-2 Yoda □ FR-2 Luke Lightsaber Training w/Remote □ 2A Anakin Skywalker Fatherless as a Child □ C-3 Owen Lars □ FR-3 Vader Vs. Kenobi Duel □ 2L Luke Skywalker Fatherless as a Child □ C-4 R2-D2 □ FR-4 Vader Interrogation □ 3A Anakin Skywalker Tatooine □ C-5 C-3PO □ FR-5 Luke's Death Star Trench Run □ 3L Luke Skywalker Tatooine □ C-6 Emperor Palpatine □ FR-6 Vader Tantive IV Entrance □ 4A Anakin Skywalker Isolation in Youth □ C-7 Princess Leia Organa □ FR-7 Luke Rescues Leia □ 4L Luke Skywalker Isolation in Youth □ C-8 Boba Fett □ FR-8 Luke in Hanger Bay □ 5A Anakin Skywalker Befriending a Droid □ C-9 Padmé Amidala □ FR-9 Vader Chokes Motti □ 5L Luke Skywalker Befriending a Droid □ C-10 The Force □ FR-10 Torched Homestead □ 6A Anakin Skywalker Death of a Guardian □ C-11 Anakin's Lightsaber □ FR-11 Luke's Crash Landing/Meeting Yoda □ 6L Luke Skywalker Death of a Guardian □ C-12 Death Star □ FR-12 Vader and His Master □ 7A Anakin Skywalker Technical Ability □ C-13 Tatooine □ FR-13 Luke Trains With Yoda in Backpack □ 7L Luke Skywalker Technical Ability □ C-14 Tusken Raiders □ FR-14 Obi-Wan and Yoda Warn Luke □ 8A Anakin Skywalker Daredevil Abilities □ C-15 Jabba The Hutt □ FR-15 In the Wampa Cave □ 8L Luke Skywalker Daredevil Abilities □ FR-16 Vader Storms Echo Base □ 9A Anakin Skywalker Fantastic Adventure Influencers □ FR-17 Luke's Mechanical Hand □ 9L Luke Skywalker Fantastic Adventure □ I-1 Qui-Gon Jinn □ FR-18 Vader Freezes Han □ 10A Anakin Skywalker Introduction to Royalty □ I-2 Shmi Skywalker □ FR-19 Vader Hires the Bounty Hunters □ 10L Luke Skywalker Introduction to Royalty □ I-3 Mace Windu □ FR-20 Vader in Meditation Chamber □ 11A Anakin Skywalker A Royal Rescue □ I-4 Ahsoka Tano □ FR-21 "Where is that shuttle going" □ 11L Luke Skywalker A Royal Rescue □ I-5 Watto □ FR-22 Luke Vs. -

![REVENGE of the JEDI ” Written by GEORGE LUCAS [REVISED] ROUGH DRAFT [June 12] © 1981 Lucasfilm Ltd](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8620/revenge-of-the-jedi-written-by-george-lucas-revised-rough-draft-june-12-%C2%A9-1981-lucasfilm-ltd-798620.webp)

REVENGE of the JEDI ” Written by GEORGE LUCAS [REVISED] ROUGH DRAFT [June 12] © 1981 Lucasfilm Ltd

STAR WARS – EPISODE VI : “REVENGE OF THE JEDI ” Written by GEORGE LUCAS [REVISED] ROUGH DRAFT [June 12] © 1981 Lucasfilm Ltd. All Rights Reserved A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away… 1. SPACE The boundless heavens serve as a backdrop for the MAIN TITLE. A ROLL-UP crawls into infinity. The Rebellion is doomed. Spies loyal to the Old Republic have reported several new armored space stations under construction by the Empire. A desperate plan to attack the Dreaded Imperial capitol of Had Abbadon and destroy the Death Stars before they are completed has been put into effect. Rebel commandos, led by Princess Leia, have made their way into the very heart of the Galactic Empire: as the first step toward the final battle for freedom…. Pan down to reveal the planet HAD ABBADON, capitol of the Galactic Empire. The gray planet’s surface is completely covered with cities and is shrouded in a sickly brown haze. Orbiting the polluted planet is a small, green, moon, a sparkling contrast to the foreboding sphere beyond. A large IMPERIAL TRANSPORT glides into frame. WE follow it, as it rockets toward the Imperial capitol. Four small TIE FIGHTERS escort the larger craft. The web-like structures of two Death Stars under construction loom in the distance as the transport approaches. Resting to one side of the half completed space station is Darth Vader’s super STAR DESTROYER and several ships of the Imperial fleet. One of the TIE Fighters escorting the Imperial transport begins to wobble and drops back with its engine sputtering. -

“Carrie Fisher Sent Me”

Unbound: A Journal of Digital Scholarship Realizing Resistance: An Interdisciplinary Conference on Star Wars, Episodes VII, VIII & IX Issue 1, No. 1, Fall 2019 “CARRIE FISHER SENT ME” Princess Leia as an avatar of resistance in the Women’s March Christina M. Knopf Keywords: Star Wars, Resistance, Women’s March A January 2017 article from the Independent led with the words, “Across the world, Carrie Fisher's rebel princess turned general become [sic] a source of hope and inspiration for women everywhere” (Loughrey 2017, para. 1). The article was loaded with images from Twitter of protest signs bearing Carrie Fisher’s visage with her iconic hair rolls superimposed with such slogans as “Woman’s Place is in the Resistance,” “We are the Resistance,” and “Rebel Scum.” Signs found in Twitter posts, news articles, and published archives revealed numerous Star Wars-inspired messages of feminist rebellion and resistance. Some featured Princess Leia as Rosie the Riveter, the emblem of the Resistance fighters tattooed on her arm or taking the place of Rosie’s employment badge on her collar. Signs recreated the Star Wars’ ITC Serif Gothic Heavy font to proclaim that “The Women Strike Back,” “The Fempire Strikes Back,” “The Estrogen Empire Strikes Back,” and “The Female Force Awakens,” others presented the Resistance insignia and/or Princess Leia’s face stating “Resistance is Built on Hope.” Some protestors dressed in a full Princess Leia costumes from A New Hope, promising to defeat the Dark Side. Some marchers paraphrased Leia’s iconic plea to Obi Wan, and declared, “We are Our Only Hope.” A sign paraphrasing Yoda argued that “Fear leads to anger. -

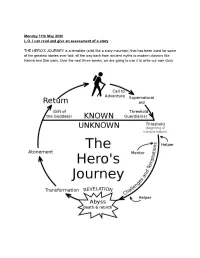

Monday 11Th May 2020 L.O. I Can Read and Give an Assessment of a Story

Monday 11th May 2020 L.O. I can read and give an assessment of a story THE HERO’S JOURNEY is a template (a bit like a story mountain) that has been used for some of the greatest stories ever told, all the way back from ancient myths to modern classics like Narnia and Star wars. Over the next three weeks, we are going to use it to write our own story One of the reasons STAR WARS is such a great movie is it because it follows the HERO’S JOURNEY model. Today, you are going to read / watch this version of the Hero’s journey and see how it fits into the format for our first act! The subtitles just refer to the stages of the story - don’t worry about them yet! Just read the story and if you have internet access look up / click on the clips on youtube. ORDINARY WORLD Luke Skywalker was a poor and humble boy who lived with his aunt and uncle in a scorching and desolate planet world called Tatooine. His job was to fix robots on the family farm and and he spent his free time flying planes through the rocky canyons. He loved his aunt and uncle but dreamed of a more exciting and adventurous life https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8wJa1L1ZCqU Search for ‘Luke Skywalker binary sunset’ CALL TO ADVENTURE One day, Luke found a broken old R2 astromech droid. It was called R2-D2 and it was a mischievous, cheeky robot who made lots of bleeps and flashes.