Diplomarbeit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Process Dynamics 1 Battle of Trafalgar (1805)

2015 Practice 1 Process dynamics Process Dynamics (W.L. Luyben) Approximate description of the battle with a continuous process. Simulate the processes A, B, C, answer the questions, provide graphs. 1 Battle of Trafalgar (1805) 32 ships led by Admiral Lord Nelson against 38 ships of the line under French Admiral Pierre- Charles Villeneuve. Ship’s destruction speed during the battle is proportional to the number of enemy ships, on the average any ship can be destroyed for a half of the day. 1. battle • Write the equation. Provide solution depending on time N(t);V (t) graphically. • Who will win? (Victory if number of enemy’s vessels = 0). How many ships should be in order to win the battle? Try system with the following parameters (a12 = 2:5; a21 = 3:8), answer the questions. • How big are the losses, how long the battle lasts? • How can ships’ destruction speed change the result? • What is the process statics (equilibrium point)? • Is the process stable or not? Calculate the eigenvalues of the system. • Provide process trajectory in the state space (N, V) and several more with other initial values (in the same graph). Find eigenvalues of the system. 2 Battle of the Atlantic (World War II) Battle between German submarines (U = 247) and British destroyers (D = 132). Ship’s destruction speed during the battle is proportional to the number of enemy ships, on the average one ship destroys 0.25 of the enemy’s ship per week. Germany produces two submarines a week. • How many destroyers a week to be produced in England in order to achieve victory in the battle? • Provide the equation to solve U(t);D(t). -

From Valmy to Waterloo: France at War, 1792–1815

Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket i Tromsoe - PalgraveConnect - 2011-03-08 - PalgraveConnect Tromsoe i - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9780230294981 - From Valmy to Waterloo, Marie-Cecile Thoral War, Culture and Society, 1750–1850 Series Editors: Rafe Blaufarb (Tallahassee, USA), Alan Forrest (York, UK), and Karen Hagemann (Chapel Hill, USA) Editorial Board: Michael Broers (Oxford, UK), Christopher Bayly (Cambridge, UK), Richard Bessel (York, UK), Sarah Chambers (Minneapolis, USA), Laurent Dubois (Durham, USA), Etienne François (Berlin, Germany), Janet Hartley (London, UK), Wayne Lee (Chapel Hill, USA), Jane Rendall (York, UK), Reinhard Stauber (Klagenfurt, Austria) Titles include: Richard Bessel, Nicholas Guyatt and Jane Rendall (editors) WAR, EMPIRE AND SLAVERY, 1770–1830 Alan Forrest and Peter H. Wilson (editors) THE BEE AND THE EAGLE Napoleonic France and the End of the Holy Roman Empire, 1806 Alan Forrest, Karen Hagemann and Jane Rendall (editors) SOLDIERS, CITIZENS AND CIVILIANS Experiences and Perceptions of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, 1790–1820 Karen Hagemann, Gisela Mettele and Jane Rendall (editors) GENDER, WAR AND POLITICS Transatlantic Perspectives, 1755–1830 Marie-Cécile Thoral FROM VALMY TO WATERLOO France at War, 1792–1815 Forthcoming: Michael Broers, Agustin Guimera and Peter Hick (editors) THE NAPOLEONIC EMPIRE AND THE NEW EUROPEAN POLITICAL CULTURE Alan Forrest, Etienne François and Karen Hagemann -

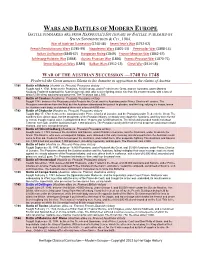

Wars and Battles of Modern Europe Battle Summaries Are from Harbottle's Dictionary of Battles, Published by Swan Sonnenschein & Co., 1904

WARS AND BATTLES OF MODERN EUROPE BATTLE SUMMARIES ARE FROM HARBOTTLE'S DICTIONARY OF BATTLES, PUBLISHED BY SWAN SONNENSCHEIN & CO., 1904. War of Austrian Succession (1740-48) Seven Year's War (1752-62) French Revolutionary Wars (1785-99) Napoleonic Wars (1801-15) Peninsular War (1808-14) Italian Unification (1848-67) Hungarian Rising (1849) Franco-Mexican War (1862-67) Schleswig-Holstein War (1864) Austro Prussian War (1866) Franco Prussian War (1870-71) Servo-Bulgarian Wars (1885) Balkan Wars (1912-13) Great War (1914-18) WAR OF THE AUSTRIAN SUCCESSION —1740 TO 1748 Frederick the Great annexes Silesia to his domains in opposition to the claims of Austria 1741 Battle of Molwitz (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought April 8, 1741, between the Prussians, 30,000 strong, under Frederick the Great, and the Austrians, under Marshal Neuperg. Frederick surprised the Austrian general, and, after severe fighting, drove him from his entrenchments, with a loss of about 5,000 killed, wounded and prisoners. The Prussians lost 2,500. 1742 Battle of Czaslau (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought 1742, between the Prussians under Frederic the Great, and the Austrians under Prince Charles of Lorraine. The Prussians were driven from the field, but the Austrians abandoned the pursuit to plunder, and the king, rallying his troops, broke the Austrian main body, and defeated them with a loss of 4,000 men. 1742 Battle of Chotusitz (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought May 17, 1742, between the Austrians under Prince Charles of Lorraine, and the Prussians under Frederick the Great. The numbers were about equal, but the steadiness of the Prussian infantry eventually wore down the Austrians, and they were forced to retreat, though in good order, leaving behind them 18 guns and 12,000 prisoners. -

Lord Nelson and the Battle of Trafalgar

Lord Nelson and the Battle of Trafalgar Lord Nelson and the early years Horatio Nelson was born in Norfolk in 1758. As a young child he wasn’t particularly healthy but he still went on to become one of Britain’s greatest heroes. Nelson’s father, Edmund Nelson, was the Rector of Burnham Thorpe, the small Norfolk village in which they lived. His mother died when he was only 9 years old. Nelson came from a very big family – huge in fact! He was the sixth of 11 children. He showed an early love for the sea, joining the navy at the age of just 12 on a ship captained by his uncle. Nelson must have been good at his job because he became a captain at the age of 20. He was one of the youngest-ever captains in the Royal Navy. Nelson married Frances Nisbet in 1787 on the Caribbean island of Nevis. Although Nelson was married to Frances, he fell in love with Lady Hamilton in Naples in Italy. They had a child together, Horatia in 1801. Lord Nelson, the Sailor Britain was at war during much of Nelson’s life so he spent many years in battle and during that time he became ill (he contracted malaria), was seriously injured. As well as losing the sight in his right eye he lost one arm and nearly lost the other – and finally, during his most famous battle, he lost his life. Nelson’s job helped him see the world. He travelled to the Caribbean, Denmark and Egypt to fight battles and also sailed close to the North Pole. -

The History of Napoleon Buonaparte

THE HISTORY OF NAPOLEON BUONAPARTE JOHN GIBSON LOCKHART CHAPTER I BIRTH AND PARENTAGE OF NAPOLEON BUONAPARTE—HIS EDUCATION AT BRIENNE AND AT PARIS—HIS CHARACTER AT THIS PERIOD—HIS POLITICAL PREDILECTIONS—HE ENTERS THE ARMY AS SECOND LIEUTENANT OF ARTILLERY—HIS FIRST MILITARY SERVICE IN CORSICA IN 1793. Napoleon Buonaparte was born at Ajaccio on the 15th of August, 1769. The family had been of some distinction, during the middle ages, in Italy; whence his branch of it removed to Corsica, in the troubled times of the Guelphs and Gibellines. They were always considered as belonging to the gentry of the island. Charles, the father of Napoleon, an advocate of considerable reputation, married his mother, Letitia Ramolini, a young woman eminent for beauty and for strength of mind, during the civil war— when the Corsicans, under Paoli, were struggling to avoid the domination of the French. The advocate had espoused the popular side in that contest, and his lovely and high-spirited wife used to attend him through the toils and dangers of his mountain campaigns. Upon the termination of the war, he would have exiled himself along with Paoli; but his relations dissuaded him from this step, and he was afterwards reconciled to the conquering party, and protected and patronised by the French governor of Corsica, the Count de Marbœuff. It is said that Letitia had attended mass on the morning of the 15th of August; and, being seized suddenly on her return, gave birth to the future hero of his age, on a temporary couch covered with tapestry, representing the heroes of the Iliad. -

The Professional and Cultural Memory of Horatio Nelson During Britain's

“TRAFALGAR REFOUGHT”: THE PROFESSIONAL AND CULTURAL MEMORY OF HORATIO NELSON DURING BRITAIN’S NAVALIST ERA, 1880-1914 A Thesis by BRADLEY M. CESARIO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2011 Major Subject: History “TRAFALGAR REFOUGHT”: THE PROFESSIONAL AND CULTURAL MEMORY OF HORATIO NELSON DURING BRITAIN’S NAVALIST ERA, 1880-1914 A Thesis By BRADLEY M. CESARIO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved by: Chair of Committee, R.J.Q. Adams Committee Members, Adam Seipp James Hannah Head of Department, David Vaught December 2011 Major Subject: History iii ABSTRACT “Trafalgar Refought”: The Professional and Cultural Memory of Horatio Nelson During Britain’s Navalist Era, 1880-1914. (December 2011) Bradley M. Cesario, B.A., University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. R.J.Q. Adams Horatio Lord Nelson, Britain’s most famous naval figure, revolutionized what victory meant to the British Royal Navy and the British populace at the turn of the nineteenth century. But his legacy continued after his death in 1805, and a century after his untimely passing Nelson meant as much or more to Britain than he did during his lifetime. This thesis utilizes primary sources from the British Royal Navy and the general British public to explore what the cultural memory of Horatio Nelson’s life and achievements meant to Britain throughout the Edwardian era and to the dawn of the First World War. -

The Battle of Trafalgar

The Battle of Trafalgar When was the Battle Of Trafalgar? It happened on 21 October 1805 off Cape Trafalgar on the coast of south west Spain. Who was involved? The battle was between the Royal Navy and a force made up of Spanish and French ships. The Royal Navy, under the command of Admiral Horatio Nelson, had 27 ships. The French and Spanish forces, under Admiral Pierre de Villeneuve, had 33 ships. Why did the battle take place? The French emperor Napoleon Bonaparte was gearing up to invade England. He had already taken over other parts of Europe and wanted to expand his empire. The two sides were in hot pursuit of each other, then they met up at Trafalgar. What happened at the battle? The French and Spanish ships were lined up in a row. Instead of lining up against them, Nelson decided to Nelson's flagship, HMS Victory attack them by forming two columns of ships, with the aim of pushing through the enemy lines and separating their ships into smaller groups. As the battle started, Nelson made a signal, using flags, to his men from his ship, HMS Victory. It said: "England expects that every man will do his duty'. He later followed that with: "Engage the enemy more closely'. The Royal Navy succeeded in piercing the enemy line. By 4.30pm, the battle was over as the last of the French and Spanish forces surrendered or were overwhelmed. What happened to Nelson? It was a great victory for the Royal Navy, but they lost the man who had led the attack. -

Calculus Challenge #14 Calculus at the Battle of Trafalgar

Calculus Challenge #14 Calculus at the Battle of Trafalgar The summer of 2005 marked the 200th anniversary of the British naval victory over a combined French and Spanish fleet in the waters off Cape Trafalgar. During the Napoleonic wars, naval warfare followed certain rules that seem rather formal to us today. The ships in each fleet lined up in a row sailing parallel to its opponent and fired as they sailed past each other (see Figure 1). This maneuver was repeated until one fleet was disabled or sunk. This is known as the directed fire model or conventional combat model. Figure 1: The White Fleet takes a beating In such an engagement, the fleet with superior firepower will inevitably win. To model this battle, we begin with a system of differential equations that models the interaction of two fleets in combat. Suppose we have two opposing forces, fleet A with A0 and fleet B with B0 ships initially, and A(t) and B(t) ships t units of time after the battle is engaged. Given the style of combat at the time of Trafalgar, the losses for each fleet will be proportional to the effective firepower of the opposing fleet. That is, dA dB =−bB and =−aA, dt dt where a and b are positive constants that measure the effectiveness of the ship’s cannonry and personnel and A and B are both functions of time. These equations indicate that the rate at which one navy lost ships depended only on two things: the number of ships in the opposing fleet and the effectiveness of the opposition fire. -

In Time, Napoleon's Battlefield Successes Forced the Rulers Of

In time, Napoleon’s battlefield successes forced the rulers of Austria, Prussia, and Russia to sign peace treaties. These successes also enabled him to build the largest European empire since that of the Romans. France’s only major enemy left unde- feated was the great naval power, Britain. The Battle of Trafalgar In his drive for a European empire, Napoleon lost only one major battle, the Battle of Trafalgar (truh•FAL•guhr). This naval defeat, how- ever, was more important than all of his victories on land. The battle took place in 1805 off the southwest coast of Spain. The British commander, Horatio Nelson, was as brilliant in warfare at sea as Napoleon was in warfare on land. In a bold maneuver, he split the larger French fleet, capturing many ships. (See the map inset on the opposite page.) The destruction of the French fleet had two major results. First, it ensured the supremacy of the British navy for the next 100 years. Second, it forced Napoleon to give up his plans of invading Britain. He had to look for another way to control his powerful enemy across the English Channel. Eventually, Napoleon’s extrava- gant efforts to crush Britain would lead to his own undoing. The French Empire During the first decade of the 1800s, Napoleon’s victories had given him mastery over most of Europe. By 1812, the only areas of Europe free from Napoleon’s control were Britain, Portugal, Sweden, and the Ottoman Empire. In addition to the lands of the French Empire, Napoleon also controlled numerous supposedly independent countries. -

Napoleonic Scholarship

Napoleonic Scholarship The Journal of the International Napoleonic Society No. 8 December 2017 J. David Markham Wayne Hanley President Editor-in-Chief Napoleonic Scholarship: The Journal of the International Napoleonic Society December 2017 Illustrations Front Cover: Very rare First Empire cameo snuffbox in burl wood and tortoise shell showing Napoleon as Caesar. Artist unknown. Napoleon was often depicted as Caesar, a comparison he no doubt approved! The cameo was used as the logo for the INS Congress in Trier in 2017. Back Cover: Bronze cliché (one sided) medal showing Napoleon as First Consul surrounded by flags and weapons over a scene of the Battle of Marengo. The artist is Bertrand Andrieu (1761-1822), who was commissioned to do a very large number of medallions and other work of art in metal. It is dated the year X (1802), two years after the battle (1800). Both pieces are from the David Markham Collection. Article Illustrations: Images without captions are from the David Markham Collection. The others were provided by the authors. 2 Napoleonic Scholarship: The Journal of the International Napoleonic Society December 2017 Napoleonic Scholarship THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL NAPOLEONIC SOCIETY J. DAVID MARKHAM, PRESIDENT WAYNE HANLEY, EDITOR-IN-CHIEF EDNA MARKHAM, PRODUCTION EDITOR Editorial Review Committee Rafe Blaufarb Director, Institute on Napoleon and the French Revolution at Florida State University John G. Gallaher Professor Emeritus, Southern Illinois University at Edwardsville, Chevalier dans l'Ordre des Palmes Académiques Alex Grab Professor of History, University of Maine Romain Buclon Université Pierre Mendès-France Maureen C. MacLeod Assistant Professor of History, Mercy College Wayne Hanley Editor-in-Chief and Professor of History, West Chester University J. -

Project Aneurin

The Aneurin Great War Project: Timeline Part 6 - The Georgian Wars, 1764 to 1815 Copyright Notice: This material was written and published in Wales by Derek J. Smith (Chartered Engineer). It forms part of a multifile e-learning resource, and subject only to acknowledging Derek J. Smith's rights under international copyright law to be identified as author may be freely downloaded and printed off in single complete copies solely for the purposes of private study and/or review. Commercial exploitation rights are reserved. The remote hyperlinks have been selected for the academic appropriacy of their contents; they were free of offensive and litigious content when selected, and will be periodically checked to have remained so. Copyright © 2013-2021, Derek J. Smith. First published 09:00 BST 30th May 2013. This version 09:00 GMT 20th January 2021 [BUT UNDER CONSTANT EXTENSION AND CORRECTION, SO CHECK AGAIN SOON] This timeline supports the Aneurin series of interdisciplinary scientific reflections on why the Great War failed so singularly in its bid to be The War to End all Wars. It presents actual or best-guess historical event and introduces theoretical issues of cognitive science as they become relevant. UPWARD Author's Home Page Project Aneurin, Scope and Aims Master References List BACKWARD IN TIME Part 1 - (Ape)men at War, Prehistory to 730 Part 2 - Royal Wars (Without Gunpowder), 731 to 1272 Part 3 - Royal Wars (With Gunpowder), 1273-1602 Part 4 - The Religious Civil Wars, 1603-1661 Part 5 - Imperial Wars, 1662-1763 FORWARD IN TIME Part -

Process Dynamics 1 Battle of Trafalgar (1805)

2014 Practice 1 Process dynamics Process Dynamics (W.L. Luyben) Approximate description of the battle with a continuous process. Simulate the processes A, B, C, answer the questions, provide graphs. 1 Battle of Trafalgar (1805) 27 ships led by Admiral Lord Nelson against 33 ships of the line under French Admiral Pierre- Charles Villeneuve. Ship’s destruction speed during the battle is proportional to the number of enemy ships, on the average any ship can be destroyed for a half of the day. 1. battle • Write the equation. Provide solution depending on time N(t);V (t) graphically • Who will win? (Victory if number of enemy’s vessels = 0). How many ships should be in order to win the battle? • How big are the losses, how long the battle lasts? • How can ships’ destruction speed change the result? • What is the process statics (equilibrium point)? • Is the process stable or not? Calculate the eigenvalues of the system. • Provide process trajectory in the state space (N, V) and several more with other initial values (in the same graph). Find eigenvalues of the system. 2. A new strategy for Nelson: fight at the beginning with half of the V ’s vessels, and later with the other part. What will happen? 2 Battle of the Atlantic (World War II) Battle between German submarines (U = 210) and British destroyers (D = 130). Ship’s destruction speed during the battle is proportional to the number of enemy ships, on the average destroys one ship 0.25 of the enemy’s ship per week. Germany produces two submarines a week.