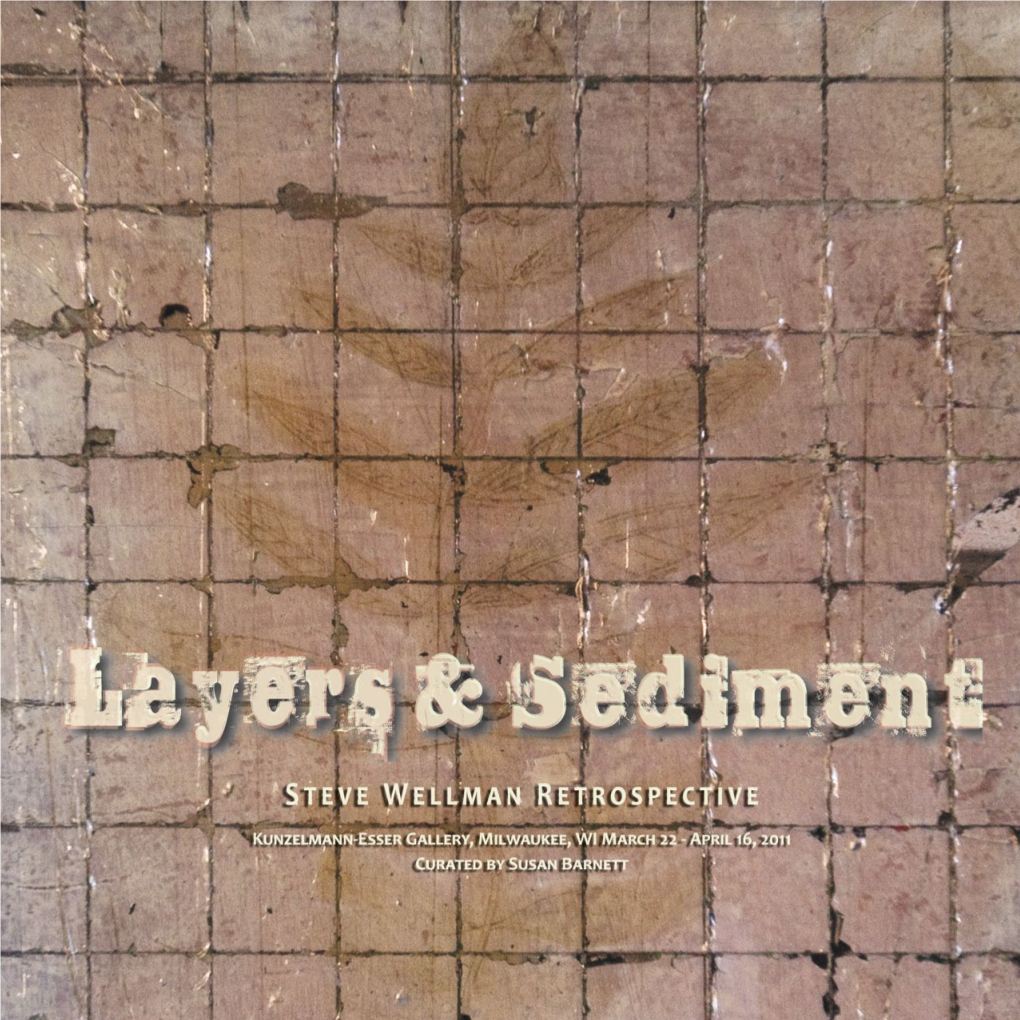

Steve Wellman Retrospective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Richard Stout: Paintings and Sculptures

RICHARD STOUT: The Arc of Perception New Paintings and Sculpture & Paintings from the 1950’s OCTOBER 20 – NOVEMBER 25, 2006 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: August 15, 2006 - Holly Johnson Gallery in Dallas unveils an exhibition of new work by Texas' most influential artist, Richard Stout, as well as a selection of paintings from the 1950’s. An opening reception for the artist will be held on Friday, October 20, from 6:00 to 8:00 p.m. The exhibition continues through Saturday, November 25, 2006. In 2001, Dr. Edmund Pillsbury writes, “Inspired by Giacometti, Ernst and other Surrealist works on view at the Menil Collection but possessing an understanding of the powers of landscape that is almost mystical, Richard Stout stands apart. He is an artist of our time, but through his works he transports us to places near and far, making us appreciate the world in fresh ways and bringing a set of emotions into our experience of daily life that, albeit clouded in mystery, is both reassuring and uplifting. He is a worthy successor to his Romantic forbearers, Turner and Delacroix, whose goal superseded any traditional concept of beauty in favor of effects that can only be described as Sublime.” And in Sculpture magazine (May 2006), Ileana Marcoulesco writes, “The sculptures appear to explore a space of intimate events – in spite of their rhetorical titles, compiled from grand mythological narratives...they are heavy, complex, versatile three-dimensional shapes. Ascetic in appearance, cryptic in connotation, yet free-wheeling, they speak a private language of passions and are hard to penetrate, except intuitively.” Stout was born in 1934 in Beaumont, Texas. -

John G. Vinklarek

JOHN VINKLAREK VITA EDUCATION MFA University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon 1973 BFA Texas Technological University, Lubbock EXPERIENCE IN HIGHER EDUCATION 1977- Present Employed as Art Instructor at Angelo State University, San Angelo, Texas (2006 Professor) Employed as a Graduate Teaching Fellow and Casting Consultant for the design of a 1975-76 foundry at the University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon OTHER CAREER EXPERIENCE 1972-74 Employed as an Artisan at Mesa Bronze Art Foundry, Lubbock, Texas JURIED SHOWS 2019 West Texas Regional Show 3rd prize sculpture San Angelo Art Club San Angelo, Texas. Midland Art Association Annual Fall Show honorable mention Midland, Texas. Laredo 30 international exhibit Laredo College, Laredo, Texas. Monmouth Museum National Show Lincroft, New Jersey. Langdon Center National Show Merit Award, Granbury, Texas. 53rd Annual Richardson Art Society Regional show First Prize Graphics Richardson, Texas 2018 52nd Annual National Drawing and Sculpture show, Del Mar College, Corpus Christi Texas. 31st Annual McNeese National Works on Paper Exhibition, McNeese State University, Lake Charles, Louisiana (Honorable Mention). 5th Annual National Juried Exhibit, Bower Center for the Arts, Bedford , Virginia. 31st Annual Northern National Art Competition, Nicolet College, Rinelander Wisconsin 2017 51nd Annual National Art Exhibit Del Mar College , Corpus Christi Texas. Langdon Center National Show, Granbury, Texas. Matte Kelly art Center National Show Pleasantville, Florida. South Cobb Art Alliance , Mabelton, Georgia. Bower Center National Show Bedford, Virginia. Crooked Tree National Competition Petosky, Michigan. Topeka Competition- National Show 4 Topeka, Kansas. Mixed media Prize Kendall art Gallery, San Angelo , Texas. 2016 50th annual National Art Exhibit Del mar College Corpus Christi, Texas. -

Suits: the Qothesmake The

FALL 1' "STlircsIinlhs SUITS: THE QOTHES MAKE THE MAN Ladies and Gentlemen: The Art Guys (have left the building.) COMMENTARY By JaMES P. O'BRIEN AND GrEG RuSSELL The Am Guys will make every effort to appear at as many events as possible THROUGHOUT 1998 TO FURTHER EXTEND THE VISIBILITY OF THE SUITS ANO THE CLIENTS REPRESENTED ON THEM: Events and appearances: Todd Oldham's Spnng Show, NY / The Academy Awards, LA / Cannes Film Festival, France / MTV Music Awards, LA / Whitney Museum, NY / Guggenheim, NY / The National Gallery, DC /The Late Show with David Letterman / Rosie O'Donnell /The Winter Olympic Games, Utah / figure 1. 1,000 coats of The Boston Marathon / NFL Football Games paint: telephone 1990-91. teieptiorre, LOOO coats of - Suits: Tlie Clothes the project itinerary. from Make Man, latex paint, glass, brass plaque, left above: in progress, riglit above: finished state, left: paint calendar year 1998 The Art Guys will enact their ctiart and brushes. In seven well-planned Suits: The Clothes Make the Man In months. 1,000 coats of project. Despite the varied physical appearances variously colored paint was applied. and manifestations of their previous works (in perfor- mance, video, photography, sculpture and assemblage,) in the Suits project they retain a certain consistency. How? The Art Guys act repeatedly with twin methods: OBSESSIVE BEHAVIOR and THE ARTIST AS FOOL. below: figure 2. left: blockhead 1996. Deer trophy, concrete, right: largemouth bass1997. Bass These twin methods have allowed them to employ such trophy, plastic lips. "We are currently working on a series of pieces involving animal trophies. -

Nov. 26, 1946 Birthplace: Denver, CO Residence: Houston Heights, Houston, TX Education: Bachelor of Fine Arts (Painting), University of Houston 1988

Wayne D. Gilbert Born: Nov. 26, 1946 Birthplace: Denver, CO Residence: Houston Heights, Houston, TX Education: Bachelor of Fine Arts (Painting), University of Houston 1988 Chronology 1986 1989 U.S.OlympicFence RepublicBankCenter,Houston,TX JuriedbyCommittee 6thAnnualJuriedFineArtExhibition GroupShow GroupShow Painting:Wrestlers Juror:MichaelPeranteau StatementbyMr.Peranteau 1987 March4-April1,1989 LosAlamosHistoricalMuseum, 1stPlace LosAlamos,NM ThirdBiennialJuriedPaintingExhibitionGroupShow LawndaleArtandPerformanceCenter, June5-July19,1987 Houston,TX Juror:KarenN.Purucker EastEndShow GroupShow TwoHoustonCenter,Houston,TX Juror:WilliamCampbell TexasArtCelebration‘87 StatementbyMr.Campbell GroupShow March4-March24,1989 March29-April25,1987 Juror:JohnCaldwell LynnGoodeGallery,Houston,TX StatementbyMr.Caldwell LongHotSummer CatalogunderwrittenbyAssistanceLeagueofHous- HoustonAreaArtistsInvitationalShow tonandtheHoustonGalleries Aug.1-Sept.6,1989 JewishCommunityCenterofHouston JewishCommunityCenter,Houston,TX Texas21stJuriedArtExhibition 22ndJuriedArtExhibition GroupShow GroupShow Sept.12-Oct.22,1987 Juror:HughM.Davies Juror:MaryJaneJacob StatementbyMr.Davies StatementbyMs.Jacob HistoricalEssaybyLynnWeycer CatalogstatementbyMs.LynnWeycer Aug.19-Sept.25,1989 1988 1990 Greenway3Theater,Houston,TX TwoHoustonCenter,Houston,TX DoItfortheGipper VisualArtsAlliance7thAnnualJuriedArtExhibition GroupShow GroupShow March1-Aug.1,1988 Juror:Unknown CuratedbyPaulaFridkinand&MichaelGalbreth March3-April7,1990 Butera’sonAlabama,Houston,TX LawndaleArtandPerformance,Houston,TX -

Umedalen Skulptur 2010 5/6–15/8 Umeå, Sweden

1 Umedalen Skulptur 2010 5/6–15/8 UMEÅ, SWEDEN Angela de la Cruz, Jacob Dahlgren, Grönlund–Nisunen, Lotta Hannerz, Michael Johansson, Per Kirkeby, Wilhelm Mundt, Trine Lise Nedreaas, Magnus Petersson, Jaume Plensa, Bjørn Poulsen, Astrid Sylwan 2 CONTENT 2010 map 4–5 Overview 6–7 Introduction 8–9 Grönlund-Nisunen 12–13 Trine Lise Nedreaas 14–15 Jacob Dahlgren 16–17 Per Kirkeby 18–19 Magnus Petersson 20–21 Angela de la Cruz 22–23 Astrid Sylwan 24–25 Wilhelm Mundt 26–27 Grönlund-Nisunen 28–29 Bjørn Poulsen 30–31 Michael Johansson 32–33 Jaume Plensa 34–35 Permanent collection 36–54 Skulptures from earlier years 55–59 In Umea City 60–67 3 5/6–15/8 Sculptures placed in the Mikael city center of Umeå 2010 map Richter p. 60–65 49 Winter & 48 Hörbelt New Sculptures 2010 p. 10–33 Jacob 50 Sculptures from Permanent Dahlgren earlier years collection Jaume p. 54–59 p. 34–52 Plensa 47 Lotta 51 Hannerz Lin Peng 1 Magnus Jacob Takashi Petersson Angela Dahlgren 46 Naraha 45 2 3 4 De La Cruz Grönlund-Nisunen Michael Raffael Rheinsberg 44 9 Trine Lise Nedreaas Johansson Jacob Dahlgren Claes Antony Kari Per Kirkeby Bård Hake Gormley Cavén 5 Breivik 43 42 41 40 38 37 Johanna Jonas Charlotte Clay Cristos 10 Buky Anna Ekström Kjellgren 6 Gyllenhammar Ketter Gianakos Schwartz Renström Bernard Astrid 39 Anne-Karin 15 7 Kirchenbaum 36 8 Sylwan Furunes 14 11 12 Torgny Gunilla Wilhelm Mundt The Art Nilsson Samberg 16 Meta Isæus Berlin Sean Guys 17 18 35 Henry Roland Mats Persson Grönlund-Nisunen 13 19 Bergqvist Kari Kaarina Cavén Kaikkonen 25 30 Louise 21 34 Bourgeois Anish Bjørn Poulsen Kapoor 20 22 23 24 26 27 28 29 31 32 33 Nina David Tony Antony Richard Cristina Carina Miroslaw Bigert & Serge Saunders Wretling Cragg Gormley Nonas Iglesias Gunnars Balka Bergström Spitzer 4 Sculptures placed in the Mikael city center of Umeå Richter p. -

1 Trinity Church in the City of Boston the Rev. Morgan S. Allen

Trinity Church in the City of Boston The Rev. Morgan S. Allen November 17, 2019 XXIII Pentecost, Luke 21:5-19 Come Holy Spirit, and enkindle in the hearts of your faithful, the fire of your Love. Amen. A 1995 New York Times article begins, “Meet The Art Guys … working as clerks for 24 hours straight at the Stop-N-Go convenience store in Houston’s museum district. They sold lottery tickets. They asked for patience when a customer couldn’t get the gas pump to work and neither could they. ‘Hey, we’re new at this,’ [explained] Michael Galbreth, [one of the two Art Guys]. They mopped the floor. And they called [all of this] art.”i According to the Times, “The Art Guys are part Dada, part David Letterman, pushing the concept of performance art to [its] outer limits.”ii Galbreth met collaborator and fellow Art Guy Jack Massing in 1982, and the pair began their creative partnership a year later. Their “work has been included in more than 150 exhibitions in museums, galleries, and public spaces throughout the United States … Europe, and China,” and they lectured as near to us as Harvard.iii Galbreth and Massing described their work “with terms like ‘pursuances,’ ‘disturbances,’ ‘procurements,’ and ‘doohickeys,’”iv using ordinary objects as unusual media in their sculptures – as in Cheese Grid (1993),v their strangely beautiful, wall-sized mosaic of American Cheese slices – and exaggerating by scale or repetition familiar actions in their “events” – as in Loop, driving Houston’s 610 freeway for 24 hours straight, 12 hours in one direction, and 12 hours in the other.vi Combining these static and dynamic elements, The Art Guys even “presciently anticipated our age of self-branding ‘influencers’ with SUITS: The Clothes Make the Man (1997- 98). -

2020 TXN Catalogue

26th Annual Juried Competition & Exhibition Catalog May 5 - June 13, 2020 Cover Design by André Gagnon Juror Annette Lawrence, Professor of Studio Art, College of Visual Arts and Design at University of North Texas Photo Credit: Megan DeSoto Annette Lawrence’s studio practice is characterized by transforming raw data into draw- ings, objects, and installations. The data accounts for and measures everyday life. Her subjects of inquiry range from body cycles, to ancestor portraits, music lessons, unsolic- ited mail, and journal keeping. She addresses questions of text as image, and the rela- tionship between text and code. Her work is grounded in examining what counts, how it is counted, and who is counting. Her process is one of making and unmaking, looking, waiting, recognizing things that go unannounced, remain steady, continuous, unremark- able on the surface, and develop meaning over time. Lawrence’s work has been widely exhibited and is held in museums, and private col- lections including The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, The Dallas Museum of Art, The Rachofsky Collection, ArtPace Center for Contemporary Art, Jack S. Blanton Museum of Art, American Airlines and the Art Collection of the Dallas Cowboys. She received a 2018 MacDowell Fellowship, the 2015 Moss/Chumley Award from the Meadows Museum, and the 2009 Otis and Velma Davis Dozier Travel Award from the Dallas Museum of Art. Her work was included in the 1997 Biennial Exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY. She is an alumnus of the Core Program at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and the Skowhegan School. -

REGULARMAIN the Latest in Contemporary Texas Art - June Mattingly

REGULARMAIN The Latest in Contemporary Texas Art - June Mattingly FRONTPAGE BROWS E SUBSCR IBE IIs earch the archives... return home by topic rss feed II --- FEBRUARY 15, 2011• 4:51 PM • 0 Pages A Call for a Competition and Shane Mecklenburger in "Glitch" a group Exhibition show of Video Art at CentralTrak curated by o About June Mattingly John Pomara and Dean Terry o Objectsof Desire: a competition and eXhibltlon Artists and Topics Armory Show A link to my articles in The Art Guys ModAustin .net David Aylsworth WIiiiam Betts o Link to my articles In ModAustln.net Colby Bird Ed Blackbum A link to my articles in Modem Amy Blakemore Dallas.net Erika Blumenfeld Paul Booker o Please check out my articles In Troy Brauntuch ModemDallas.net and Russell Buchanan ModemHouston.net every weekl Richie Budd Angel Cabrales A link to my articles in Modern Jerry Cabrera Houston .net WIiiiam Cannlngs Douglas Leon Cartmel o Link to my article on Modemhouston.net The Chlnati Foundation Michael Craig-Martin DADA Austin Dallas Museum of Art "Glltchensteln's Monster" 2011 Alejandro Diaz o Arthouse at the Jones Center Kent Dorn o Austin Museum of Art Jeff Elrod Shane and I met through a mutual artist/friend In not exactly a "serene• setting o d.berman at the show's opening and again two weeks later at Centraltrak to hear two of Vincent Falsetta o Okay Mountain the conl/lbuting artists discuss their art to an engrossed audience surrounded Joey Fauerso Tony Feher by theoreticallymesmerizi ng art on the walls. The versatility of the artistic Vernon Fisher technologlcal feats possible on a computer and the reference to •a computer Corpus Christi Sean Fitzgerald glitch" In the show's title an of a sudden poppedwi de open. -

“In November of 2002, the Wheeler Bro's Blew Into Houston Like a Dust

“In November of 2002, the Wheeler Bro’s blew into Houston like a dust storm to present ULTERIOR MOTIFS no. 4, creating a whirlwind extravaganza of paintings, drawings, and shit-kicking shenanigans…after the dust had settled, we were left wondering what hit us as they drove off into the sunset in their paint-spattered boots, tailgates down, to their next appointment with art destiny.” -The Art Guys It all began on the lonely dusty Plains of West Texas…Lubbock to be exact. Living in a cavernous downtown building and having lots and lots of new unseen art, artists and brothers, Jeff and Bryan Wheeler, dreamed up what would become an annual excuse to have a city-wide party to highlight their own art and music. (Bryan is also the frontman for Lubbock band, LOS SONSABITCHES). The Wheeler Brothers invited their artist and musician friends to unite for a free-wheeling celebratory art show that from the very beginning featured such measured craziness as opening ceremonies, real live Texas Tech cheerleaders, wandering musicians and magicians, Elvis impersonators, and lots more surprises at every turn. ULTERIOR MOTIFS was born. By UM no. 3, Ulterior Motifs was a much anticipated annual Lubbock event complete with real sponsors, over 1,000 revelers, and real art world reviews. Word got out to the rest of Texas, and in in 2002, the Wheeler brothers were invited by infamous Texas artists, The Art Guys, to bring their art extravaganza on the road to the famous ART GUYS WORLS HEADQUARTERS in Houston, Texas. As Catherine D. Anspon writes in her 2010 book, TEXAS ARTISTS TODAY, “The [Houston] debut provided imprimatur and just the right amount of insouciance to launch them into mainstream contemporary circles in Texas…” That night, the Wheeler brothers met famous Houston art people such as Gus Kopriva and Wayne Gilbert. -

The Art Car Spectacle: a Cultural Display And

THE ART CAR SPECTACLE: A CULTURAL DISPLAY AND CATALYST FOR COMMUNITY Dawn Stienecker, MEd Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2012 APPROVED: Rina Kundu, Major Professor Nadine Kalin, Co-major Professor Connie Newton, Committee Member Denise A. Baxter, Interim Chair of the Department of Art Education and Art History Robert W. Milnes, Dean of the College of Visual Arts and Design Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Stienecker, Dawn. The Art Car Spectacle: A Cultural Display and Catalyst for Community. Doctor of Philosophy (Art Education), August 2012, 231 pp., 11 illustrations, reference list, 120 titles. This auto-ethnographic study focuses on Houston’s art car community and the grassroots movement’s 25 year relationship with the city through an art form that has created a sense of community. Art cars transform ordinary vehicles into personally conceived visions through spectacle, disrupting status quo messages of dominant culture regarding automobiles and norms of ownership and operation. An annual parade is an egalitarian space for display and performance, including art cars created by individuals who drive their personally modified vehicles every day, occasional entries by internationally renowned artists, and entries created by youth groups. A locally proactive public has created a movement has co-opted the cultural spectacle, creating a community of practice. I studied the events of the Orange Show Center for Visionary Art’s Art Car Weekend to give me insight into art and its value for people in this community. Sources of data included the creation of a participatory art car, journaling, field observation, and semi-structured interviews. -

Artist's Resumé

Artist’s Resumé Louis Theodore “Ted” Ollier 86 Powder House Blvd #3 Somerville, MA 02144 617.633.1816 [email protected] BA Honors Liberal Arts, University of Texas at Austin, 1993; 3.381 Dual BFA Communication Design & Studio Art, Texas State University, San Marcos, 2004; 3.786 MFA, Massachusetts College of Art, 2008 Experience: Founding member of Ars Ipsa artist-funded guerilla gallery Founding member of Progressions collectors circle Presentation, ArtH 4301 Class, Texas State University; How to Start Your Own Gallery , April 18, 2006; Dr. James Housefield, instructor Member, Slugfest print cooperative, Austin, TX Member, EES-Arts print cooperative, Boston, MA Printmaking tutor and studio assistant, MassArt Low Residency MFA Program at the Fine Arts Work Center, Provincetown, MA Adjunct tutor and printer, Bow & Arrow Press, Adams House, Harvard University Shows (solo in bold): 2004 They Who Search Gallery, Austin; Handsome Fur-Bearing Animals , Apr. 2; The Art Guys, jurors Gallardia Gallery, San Marcos, Texas; Handsome Fur-Bearing Animals , Apr. 19-May 14 House Showing, Austin; Opus V: Black and White , Jun 24; Anthony Campbell, curator Gomez Art Gallery, Lincoln, Nebraska; Down ‘n’ Dirtier Art Show II , Oct 8-9; found art Gallery II, Texas State University, San Marcos, Texas; All-Student Juried Competition , Nov. 9-23; Clint Willour, juror Iron Gate Studios, Austin; Stays Crispy in Milk*, Nov 19-21; Mary Quin Matteson, juror 2005 Stone Metal Press, San Antonio; Hand-Pulled Prints XII , Mar 31-Apr 30; Frances Colpitt, juror Gallery -

Stage Environment: You Didn't Have to Be There September 8–October

Stage Environment: You Didn’t Have to Be There Contemporary Arts Museum Houston Stage Environment: You Didn’t Have to Be There September 8–October 21, 2018 Please do not remove from gallery. 1 Stage Environment: You Didn’t Have to Be There Contemporary Arts Museum Houston DOUGLAS DAVIS After CAMH flooded in 1976, Director Jim Harithas decided to use the city as his extended museum. One notable performance took place on December 20, 1976 in the Astrodome. The art and interactive technology pioneer Douglas Davis broadcast the first live global satellite performance in Houston. This was one of the early uses of live satellite technology for artistic purposes, as well as one of the first times a private citizen had rented satellite time. CAMH could only afford to rent the Astrodome for thirty-minutes, which translated to ten minutes of direct transmission. During the performance Davis read seven thoughts to a live international satellite audience and an empty Astrodome; he then put the seven sheets of paper that contained the seven thoughts in a sealed box that was never to be opened. Douglas said that these thoughts were “peaceful resistance against the idea that only the mighty and powerful could speak or broadcast to the world.” Seven Thoughts (1976) is an example of technology-based performance engaging a live audience without proximity to the performer. Please do not remove from gallery. 2 Stage Environment: You Didn’t Have to Be There Contemporary Arts Museum Houston Photograph of Astrodome, Houston, Texas Douglas Davis Seven Thoughts (documentation), 1976 NTSC single-channel video: color, sound, 32 minutes Video by Andy Mann, Dale Brooks, and Rita Myers Courtesy Video-Forum of Neuer Berliner Kunstverein (n.b.k.), Germany Douglas Davis Seven Thoughts (performance still), 1976 Photograph Copyright Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Courtesy Center for Advanced Visual Studies Special Collection, MIT Program in Art, Culture, and Technology Please do not remove from gallery.