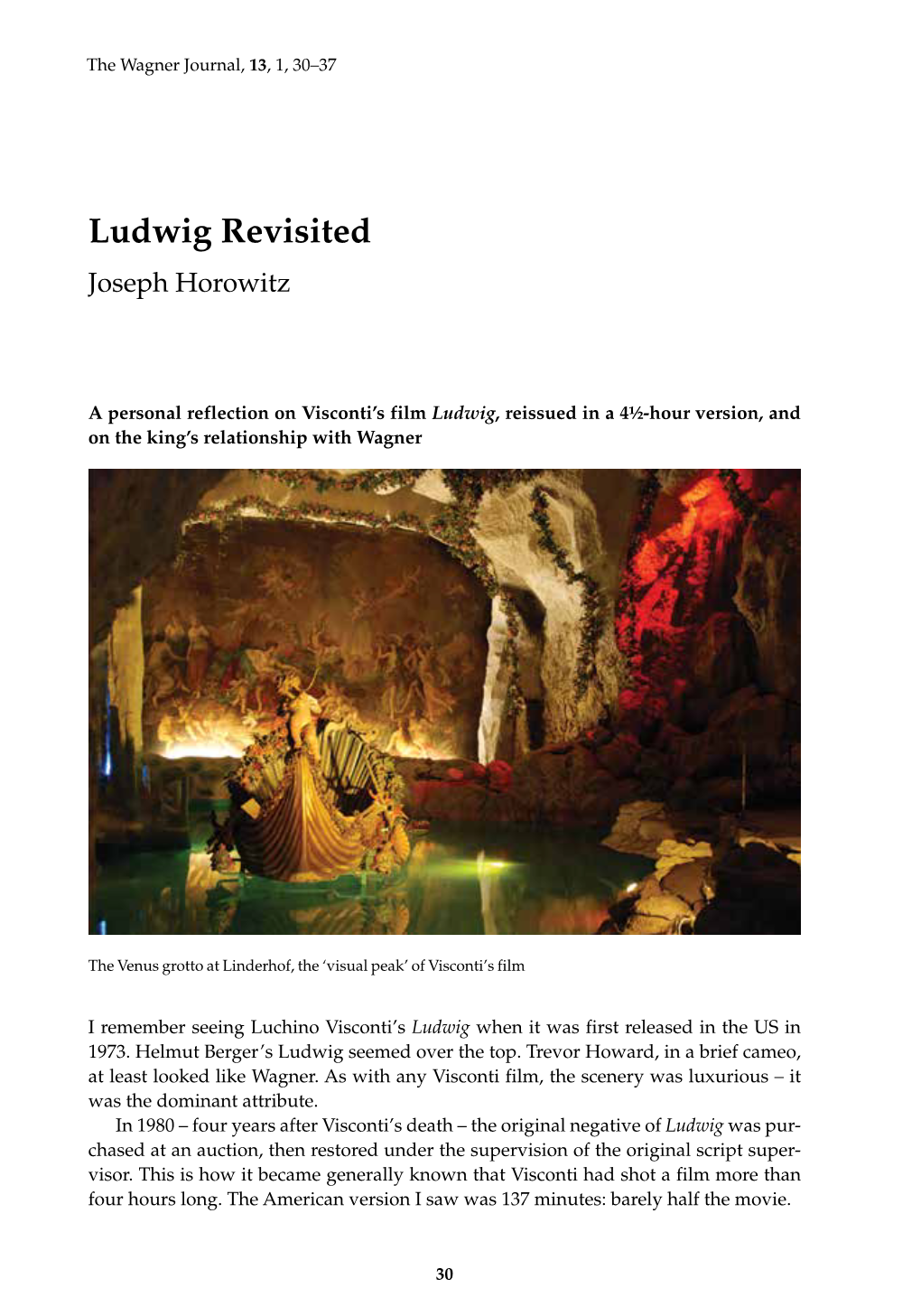

Ludwig Revisited Joseph Horowitz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

The American Film Musical and the Place(Less)Ness of Entertainment: Cabaret’S “International Sensation” and American Identity in Crisis

humanities Article The American Film Musical and the Place(less)ness of Entertainment: Cabaret’s “International Sensation” and American Identity in Crisis Florian Zitzelsberger English and American Literary Studies, Universität Passau, 94032 Passau, Germany; fl[email protected] Received: 20 March 2019; Accepted: 14 May 2019; Published: 19 May 2019 Abstract: This article looks at cosmopolitanism in the American film musical through the lens of the genre’s self-reflexivity. By incorporating musical numbers into its narrative, the musical mirrors the entertainment industry mise en abyme, and establishes an intrinsic link to America through the act of (cultural) performance. Drawing on Mikhail Bakhtin’s notion of the chronotope and its recent application to the genre of the musical, I read the implicitly spatial backstage/stage duality overlaying narrative and number—the musical’s dual registers—as a means of challenging representations of Americanness, nationhood, and belonging. The incongruities arising from the segmentation into dual registers, realms complying with their own rules, destabilize the narrative structure of the musical and, as such, put the semantic differences between narrative and number into critical focus. A close reading of the 1972 film Cabaret, whose narrative is set in 1931 Berlin, shows that the cosmopolitanism of the American film musical lies in this juxtaposition of non-American and American (at least connotatively) spaces and the self-reflexive interweaving of their associated registers and narrative levels. If metalepsis designates the transgression of (onto)logically separate syntactic units of film, then it also symbolically constitutes a transgression and rejection of national boundaries. In the case of Cabaret, such incongruities and transgressions eventually undermine the notion of a stable American identity, exposing the American Dream as an illusion produced by the inherent heteronormativity of the entertainment industry. -

What Cant Be Coded Can Be Decorded Reading Writing Performing Finnegans Wake

ORBIT - Online Repository of Birkbeck Institutional Theses Enabling Open Access to Birkbecks Research Degree output What cant be coded can be decorded Reading Writing Performing Finnegans Wake http://bbktheses.da.ulcc.ac.uk/198/ Version: Public Version Citation: Evans, Oliver Rory Thomas (2016) What cant be coded can be decorded Reading Writing Performing Finnegans Wake. PhD thesis, Birkbeck, University of London. c 2016 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit guide Contact: email “What can’t be coded can be decorded” Reading Writing Performing Finnegans Wake Oliver Rory Thomas Evans Phd Thesis School of Arts, Birkbeck College, University of London (2016) 2 3 This thesis examines the ways in which performances of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake (1939) navigate the boundary between reading and writing. I consider the extent to which performances enact alternative readings of Finnegans Wake, challenging notions of competence and understanding; and by viewing performance as a form of writing I ask whether Joyce’s composition process can be remembered by its recomposition into new performances. These perspectives raise questions about authority and archivisation, and I argue that performances of Finnegans Wake challenge hierarchical and institutional forms of interpretation. By appropriating Joyce’s text through different methodologies of reading and writing I argue that these performances come into contact with a community of ghosts and traces which haunt its composition. In chapter one I argue that performance played an important role in the composition and early critical reception of Finnegans Wake and conduct an overview of various performances which challenge the notion of a ‘Joycean competence’ or encounter the text through radical recompositions of its material. -

Download PDF Booklet

NA596012D 7070th Anniversary Edition BOOK I: THE BOOK OF THE PARENTS [The fall] 1 ‘riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s…’ 10:18 The scene is set and the themes of history, the fall, the twin brothers and ‘Bygmester Finnegan’ set out. HCE has fallen (‘Hic Cubat Edilis’), we have attended his wake, and now he lies like a giant hill beside his Liffeying wife (Apud Libertinam Parvulam). 2 ‘Hence when the clouds roll by, jamey...’ 5:28 We enter the Wellington museum in Phoenix Park (‘The Willingdone Museyroom’). The mistress Kathe is our guide. 3 ‘So This Is Dyoublong?’ 7:03 Leaving the museum we find the landscape transformed into an ancient battlefield and recall the events of 566 and 1132 AD as recalled in ‘the leaves of the living of the boke of the deeds’. A strange looking foreigner appears over the horizon. It is a Jute. He converses with a suspicious native Irelander: Mutt. Mutt’s exclamation ‘Meldundleize!’ is the first of many references to Isolde’s final aria, the Liebestod, from Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, which begins: ‘Mild und leise...’ 4 ‘(Stoop) if you are abcedminded, to this claybook…’ 7:17 We are brought back abruptly to the present and to tales hinting at scandal. Gradually the wake scene re-emerges: ‘Anam muck an dhoul (soul to the devil)! Did ye drink me doornail!’ HCE (Mr Finnemore) is encouraged to lie easy. There’s nothing to be done about it – either the sin was committed or it wasn’t. Either way it was HCE who caused the hubbub in the first place. -

WAGNER and the VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’S Works Is More Closely Linked with Old Norse, and More Especially Old Icelandic, Culture

WAGNER AND THE VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’s works is more closely linked with Old Norse, and more especially Old Icelandic, culture. It would be carrying coals to Newcastle if I tried to go further into the significance of the incom- parable eddic poems. I will just mention that on my first visit to Iceland I was allowed to gaze on the actual manuscript, even to leaf through it . It is worth noting that Richard Wagner possessed in his library the same Icelandic–German dictionary that is still used today. His copy bears clear signs of use. This also bears witness to his search for the meaning and essence of the genuinely mythical, its very foundation. Wolfgang Wagner Introduction to the program of the production of the Ring in Reykjavik, 1994 Selma Gu›mundsdóttir, president of Richard-Wagner-Félagi› á Íslandi, pre- senting Wolfgang Wagner with a facsimile edition of the Codex Regius of the Poetic Edda on his eightieth birthday in Bayreuth, August 1999. Árni Björnsson Wagner and the Volsungs Icelandic Sources of Der Ring des Nibelungen Viking Society for Northern Research University College London 2003 © Árni Björnsson ISBN 978 0 903521 55 0 The cover illustration is of the eruption of Krafla, January 1981 (Photograph: Ómar Ragnarsson), and Wagner in 1871 (after an oil painting by Franz von Lenbach; cf. p. 51). Cover design by Augl‡singastofa Skaparans, Reykjavík. Printed by Short Run Press Limited, Exeter CONTENTS PREFACE ............................................................................................ 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 7 BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF RICHARD WAGNER ............................ 17 CHRONOLOGY ............................................................................... 64 DEVELOPMENT OF GERMAN NATIONAL CONSCIOUSNESS ..68 ICELANDIC STUDIES IN GERMANY ......................................... -

Copyright © 2012 by Martin M. Van Brauman THEOLOGICAL AND

THEOLOGICAL AND CULTURAL ANTI-SEMITISM MANIFESTING INTO POLITICAL ANTI-SEMITISM MARTIN M. VAN BRAUMAN The Lord appeared to Solomon at night and said to him I have heard your prayer and I have chosen this place to be a Temple of offering for Me. If I ever restrain the heavens so that there will be no rain, or if I ever command locusts to devour the land, or if I ever send a pestilence among My people, and My people, upon whom My Name is proclaimed, humble themselves and pray and seek My presence and repent of their evil ways – I will hear from Heaven and forgive their sin and heal their land. 2 Chronicles 7:12-14. Political anti-Semitism represents the ideological weapon used by totalitarian movements and pseudo-religious systems.1 Norman Cohn in Warrant for Genocide: The Myth of the Jewish World-Conspiracy and the Protocols of the Elders of Zion wrote that during the Nazi years “the drive to exterminate the Jews sprang from demonological superstitions inherited from the Middle Ages.”2 The myth of the Jewish world-conspiracy developed out of demonology and inspired the pathological fantasy of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which was used to stir up the massacres of Jews during the Russian civil war and then was adopted by Nazi ideology and later by Islamic theology.3 Most people see anti-Semitism only as political and cultural anti-Semitism, whereas the hidden, most deeply rooted and most dangerous source of the evil has been theological anti-Semitism stemming historically from Christian dogma and adopted by and intensified with -

Malinconico Ludwig Studiava Da Attore

MALINCONICO LUDWIG STUDIAVA DA ATTORE La prima tentazione è quella di definire Ludwig 1881, il film dei fratelli Donatello e Fosco Dubini presentato in concorso a Locarno, un omaggio a vent'anni di distanza al "classico" di Luchino Visconti. Se la si guarda meglio, però, questa piccola produzione svizzero-tedesca dai meriti superiori al budget (è uno tra i titoli migliori visti finora al festival) dispone di un'autonomia molto precisa dal suo - presunto - modello alto. In primo luogo nel modo con cui gli sceneggiatori hanno concepito il mitico re di Baviera; poi nel tono sommesso e intimo, là dove la versione viscontiana era fastosa e magniloquente; e ancora in una continua vena d'ironia, rappresentata da una coppia di valletti alla Rosencrantz e Guildenstern che commentano tutta l'azione. Ludwig 1881 racconta un episodio autentico della vita del re, testimoniato da un carteggio fra Ludwig e il suo amante, nonché attore alla corte di Monaco, Josef Kainz. Nell'estate dell'81 i due uomini viaggiano in incognito sul lago dei Quattro Cantoni, celati sotto pseudonimi presi a prestito da Victor Hugo. Il re vuole che l'attore gli reciti scene del Guglielmo Tell di Schiller sullo sfondo degli scenari naturali svizzeri e - per renderne più convincente l'immedesimazione, lo spinge a camminate fra le nevi perenni o a levatacce per vedere l'alba sul Rigi. Ma la quota di "Sturm und Drang" del giovanotto si rivelerà molto al di sotto delle regali aspettative. Eppure il film dei Dubini un elemento in comune con quello di Visconti lo ha, ed è la presenza di Helmut Berger: Ludwig per eccellenza (benché altri attori abbiano interpretato il ruolo del re di Baviera, nella versione di Sjberberg e altrove) tornato a vestire il personaggio con tratti rinnovati e maggiore sicurezza interpretativa. -

October 1936) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 10-1-1936 Volume 54, Number 10 (October 1936) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 54, Number 10 (October 1936)." , (1936). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/849 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ETUDE zJxtusic ^Magazine ©ctefoer 1936 Price 25 Cents ENSEMBLES MAKE INTERESTING RECITAL NUVELTIES PIANO Pianos as are Available The Players May Double-Up on These Numbers Employing as Many By Geo. L. Spaulding Curtis Institute of Music Price. 40 cents DR. JOSEF HOFMANN, Director Faculty for the School Year 1936-1937 Piano Voice JOSEF HOFMANN, Mus. D. EMILIO de GOGORZA DAVID SAPERTON HARRIET van EMDEN ISABELLE VENGEROVA Violin Viola EFREM ZIMBALIST LEA LUBOSHUTZ Dr. LOUIS BAILLY ALEXANDER HILSBERG MAX ARONOFF RUVIN HEIFETZ Harp Other Numbers for Four Performers at One Piamo Violincello CARLOS SALZEDO Price Cat. No. Title and Composer Cat. No. Title and Composer 26485 Song of the Pinas—Mildred Adair FELIX SALMOND Accompanying and $0.50 26497 Airy Fairies—Geo. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae VIRGINIA L. LEWIS, Ph.D. Department of Languages, Literature, and Communication Studies Tech Center 248 Northern State University | 1200 S. Jay Street Aberdeen SD 57401 (605)216-7383 [email protected] https://www.northern.edu/directory/ginny-lewis EDUCATION 1983-1989 UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA 1989 Ph.D. in Modern German Literature Dissertation: “The Arsonist in Literature: A Thematic Approach to the Role of Crime in German Prose from 1850-1900,” Horst S. Daemmrich, Director 1986 M.A. in German Literature 1987-1988 UNIVERSITÄT HAMBURG DAAD Fellow: Doctoral research on crime, literature, and society in 19th-century Germany. Advisors: Jörg Schönert, Joachim Linder 2007-08 SHENANDOAH UNIVERSITY Graduate Professional Certificate in TESOL (Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages) 2016 ONLINE LEARNING CONSORTIUM OLC Certificate in Online Teaching 1977-1983 AUBURN UNIVERSITY 1981-1983 Graduate work in French Literature, completion of German major 1981 B.A. with Highest Honors in French and Art History Rome ‘81 Italian Summer Program in Art History 1979-1980 UNIVERSITÉ DE PARIS, ÉCOLE NORMALE DE MUSIQUE Sweet Briar College Junior Year in France 1978-1979 UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN Recipient of two Diplomes d'Honneur from the French Department PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 2014-date Professor of German, Northern State University Member, Graduate Faculty 2012-2015 Chair, Department of Languages, Literature, and Communication Studies, Northern State University 2009-2014 Associate Professor of German, Northern State University -

Helmut Berger

Helmut Berger www.official-helmut-berger.com Helmut Werner Management GmbH Helmut Werner Phone: +43 676 3814 054 Email: [email protected] Website: www.helmutwernermanagement.at Information Acting age 55 - 80 years Nationality Austrian Year of birth 1944 (77 years) Languages German: native-language Height (cm) 180 English: fluent Weight (in kg) 78 Spanish: medium Eye color blue green French: fluent Hair color Blond Italian: fluent Hair length Short Dialects Austrian Stature slim Profession Speaker, Actor Place of residence Salzburg Housing options Rom, Paris, Wien, Berlin, Köln, München, London, Madrid, Barcelona Film 2016 Timeless Director: Alexander Tuschinski 2014 Saint Laurent Director: Bertrand Bonelli 2013 Paganini - Der Teufelsgeiger Director: Bernhard Rose 2011 Mörderschwestern Director: Peter Kern 2009 Blutsfreundschaft / Imitation Director: Peter Kern 2008 Iron Cross Director: Joshua Newton 2005 Damals warst du still Director: Rainer Matsutani 2004 Honey Baby Director: Mika Kaurismäki 2002 Zapping Alien Director: Vitus Zeplichal 1999 Unter den Palmen Director: Miriam Kruishoop Vita Helmut Berger by www.castupload.com — As of: 2021-07- 21 Page 1 of 4 1997 Die 120 Tage von Bottrop - Der letzte neue deutsche Film Director: Christoph Schlingensief 1996 Teo Director: Cinzia TH Torlinie 1996 L'Ombre du pharaon Director: Ben Barka 1996 Last Cut Director: Marcello Avallone 1995 Die Affäre Dreyfus Director: Yves Bisset 1993 Boomtown Director: Christoph Schere 1993 Ludwig 1881 Director: Donatello & Fosco Dubini 1993 Van Loc: Un -

Ludwig, a King on the Moon Madeleine Louarn Frédéric

LUDWIG, A KING ON THE MOON A mad and legendary king, a king who never really wanted to be king, Ludwig EN II of Bavaria is as admired today as he was despised and misunderstood / during his reign. The man who wrote “I wish to remain an eternal enigma to myself and to others” succeeded beyond his wildest dreams. It is this mysterious and explosive character that Madeleine Louarn and her handicapped actors, with whom she has been working for over 20 years, have decided to put at the centre of their next show. With their faithful companions, writer Frédéric Vossier, composer Rodolphe Burger, and choreographers Loïc Touzé and Agnieszka Ryszkiewicz, they explore the fantasies and dreams of this most romantic of kings. A multi-faceted king, Ludwig II questioned the border between “normal” and “abnormal” and sought to live to the end the excessive lyricism of romanticism as a critique of modern life. The actors of the Catalyse workshop follow the slow disintegration of the monarch, his progressive withdrawal from real life and into a world of fiction. From this downfall, they create a journey into the mind of Ludwig II, and build a landscape-play in which nature, arts, and excess all lead to the fantastic. MADELEINE LOUARN It is as a special needs educator that Madeleine Louarn discovered theatre in a centre for the mentally handicapped in Morlaix. There, she created the Catalyse workshop, dedicated to amateur performance, before deciding to dedicate herself fully to her job as a director and to found in 1994 her professional company, the Théâtre de l’Entresort. -

Book Factsheet Patricia Highsmith

Book factsheet Patricia Highsmith Crime fiction, General Fiction 448 pages Published by Diogenes as Der süße Wahn January 2014 Original title: This Sweet Sickness World rights are handled by Diogenes Movie adaptations 2016: A Kind Of Murder Director: Andy Goddard Screenplay: Susan Boyd Cast: Patrick Wilson, Jessica Biel, Haley Bennett 2015: Carol / Salz und sein Preis Director: Todd Haynes Screenplay: Phyllis Nagy Cast: Cate Blanchett, Rooney Mara und Kyle Chandler 2014: The two faces of January Director: Hossein Amini Screenplay: Hossein Amini Cast: Kirsten Dunst, Viggo Mortensen, Oscar Isaac 2009: Cry of the Owl Director: Jamie Thraves Screenplay: Jamie Thraves Cast: Paddy Considine, Julia Stiles 2005: Ripley under Ground Director: Roger Spottiswoode Cast: Barry Pepper, Tom Wilkinson, Claire Forlani 1999: The Talented Mr. Ripley Director: Anthony Minghella Cast: Matt Damon, Gwyneth Paltrow, Jude Law, Cate Blanchett 1996: Once You Meet a Stranger Director: Tommy Lee Wallace Cast: Jacqueline Bisset, Mimi Kennedy, Andi Chapman 1993: Trip nach Tunis Director: Peter Goedel Cast: Hunt David, Sillas Karen 1991: Der Geschichtenerzähler Director: Rainer Boldt Cast: Christine Kaufmann, Udo Schenk, Anke Sevenich 1989: A Curious Suicide Director: Bob Biermann Cast: Nicol Williamson, J. Lapotaire 1989: Le jardin des Disparus Director: Mai Zetterling Cast: Ian Holm, Eileen Atkins 1989: L´Amateur de Frissons Director: Roger Andrieux Cast: Jean-Pierre Bisson, Marisa Berenson 1 / 7 Movie adaptations (cont'd) 1989: L´Epouvantail Director: Maroun Bagdad Cast: Jean-Pierre Cassel, J. Fox 1989: La ferme du malheur Director: Samuel Fuller Cast: Philippe Léotard, Assumpta Serna, Chris Campion 1989: Legitime Défense Director: John Berry Cast: T. Weld, D.