Volume 08 Number 03

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE OXFORD LIBRARY SALE & a Cabinet of Curiosities

Mallams 1788 THE OXFORD LIBRARY SALE & A Cabinet of Curiosities. 27th and 28th September 2017 Chinese, Indian, Islamic & Japanese Art One of a pair of 25th & 26th October 2017 Chinese trade paintings, Final entries by September 27th 18th century £3000 – 4000 Included in the sale For more information please contact Robin Fisher on 01242 235712 or robin.fi[email protected] Mallams Auctioneers, Grosvenor Galleries, 26 Grosvenor Street Mallams Cheltenham GL52 2SG www.mallams.co.uk 1788 Jewellery & Silver A natural pearl, diamond and enamel brooch, with fitted Collingwood Ltd case Estimate £6000 - £8000 Wednesday 15th November 2017 Oxford Entries invited Closing date: 20th October 2017 For more information or to arrange a free valuation please contact: Louise Dennis FGA DGA E: [email protected] or T: 01865 241358 Mallams Auctioneers, Bocardo House, St Michael’s Street Mallams Oxford OX1 2EB www.mallams.co.uk 1788 BID IN THE SALEROOM Register at the front desk in advance of the auction, where you will receive a paddle number with which to bid. Take your seat in the saleroom and when you wish to bid, raide your paddle and catch the auctioneer’s attention. LEAVE A COMMISSION BID You may leave a commission bid via the website, by telephone, by email or in person at Mallams’ salerooms. Simply state the maximum price you would like to pay for a lot and we will purchase it for you at the lowest possible price, while taking the reserve price and other bids into account. BID OVER THE TELEPHONE Book a telephone line before the sale, stating which lots you would like to bid for, and we will call you in time for you to bid through one of our staff in the saleroom. -

Tiountfee of Oxford and Berks, Or Some Or One of Them

4373 tiountfee of Oxford and Berks, or some or one of said parishes, townships, and extra-parochial or them, or in the parish of South. Hinksey, in other places, or any of them, which it may be neces- the liberty of the city of Oxford, and the county sary to stop up, alter,, or divert by reason of the of Berks, and terminating at or near the poiat construction of the said intended works. of junction of the London and Birmingham and Midland Railways, at or near Rugby, in the And it is farther intended, by such Act or Acts,, parish of Rugby, in the county of Warwick; to vary or extinguish all existing rights of' privi- which said intended railway or railways, and leges in any manner connected with the lands pro- other works connected therewith, will pass from, posed to be purchased or taken for the purposes in, through, or into, or be situate within the of the said undertaking, or which would in any Several parishes, townships, and extra-parochial manner impede or interfere with the construction, or other places following, or some of them (that is maintenance, or use thereof; and to confer other to say), South Hinksey and North Hinksey, in= the rights and privileges. liberty of the city of Oxford, and in the county of Berks, or one of them; Cumner and Botley, in the And it is also intended, by such Act or Acts, county of Berks; St. Aldate, and the liberty of the either to enable the Great Western Railway Com- Grand Pont, in the city of Oxford, and counties of pany to carry into effect the said intended under- Oxford and Berks, or some or one of them; Saint taking^ or otherwise to incorporate a company, for Ebbes, St. -

Punishment in the Victorian Workhouse Samantha Williams

Journal of British Studies 59 (October 2020): 764–792. doi:10.1017/jbr.2020.130 © The North American Conference on British Studies, 2020. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Paupers Behaving Badly: Punishment in the Victorian Workhouse Samantha Williams Abstract The deterrent workhouse, with its strict rules for the behavior of inmates and boundaries of authority of the workhouse officers, was a central expression of the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, known widely as the New Poor Law. This article explores for the first time the day-to-day experience of the power and authority of workhouse masters, matrons, other officers of the workhouse, and its Board of Guardians, and the resistance and agency of resentful inmates. Despite new sets of regulations to guide workhouse officers in the uniform imposition of discipline on residents, there was a high degree of regional diversity not only in the types of offenses committed by paupers but also in welfare policy relating to the punishments inflicted for disorderly and refractory behavior. And while pauper agency was significant, it should not be over- stated, given the disparity in power between inmates and workhouse officials. he workhouse was a central feature of Britain’s New Poor Law Amend- Tment Act of 1834, and discipline and punishment for transgressions -

Bicester Historian Issue: 8 April 2015 the Monthly Newsletter for Bicester Local History Society

Bicester Historian Issue: 8 April 2015 The monthly newsletter for Bicester Local History Society Contents Big Babies, Beer Chairman’s Ramblings . 2 St Albans Trip . 2 & Buckled Wheels Archive Update . 3 At 11:30am on Easter Monday in 1962 a Marj’s Memories . 3 large, excited, roaring crowd in a holiday Bygone Bicester . 3 mood gathered in the town centre. They Seven-a-Side Rugby . 4 were there to see the Comic Pram Race, Luftwaffe Crash . 4 organised by the Bicester Round Table. A Village History . 5 charity event that received so much support that it went on to become an annual event Roll of Honour . 5 that ran for a number of years. Talks Update . 6 The Bicester Advertiser later reported The English Parish Talk . 6 that the event was a tremendous and boisterous success, as competitors, sporting Dates For Your Diary flamboyant hats, dressed in fantastic infants clothes and sucking succulent dummies and Travelling in the Middle bottles, drew loud peals of laughter and delight from the thronging people surging in Ages Talk their hundreds down Sheep Street. 20th April - 7:30pm An astounding assembly of bizarre buns at a stall with indigestible speed, but see page 6 prams were lined up. Some donated, some victory was by now in sight. borrowed, and others taken out of ditches. Messrs. Pat Smith and Edward Shaw, May Newsletter Mr F.T.J. Hudson JP, brandishing a representing the White Lion, passed the Submissions Deadline pistol, started the race in Bell Lane with winning line first, having completed the 24th April a resounding shot. -

Thames Valley Papists from Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829

Thames Valley Papists From Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829 Tony Hadland Copyright © 1992 & 2004 by Tony Hadland All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without prior permission in writing from the publisher and author. The moral right of Tony Hadland to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0 9547547 0 0 First edition published as a hardback by Tony Hadland in 1992. This new edition published in soft cover in April 2004 by The Mapledurham 1997 Trust, Mapledurham HOUSE, Reading, RG4 7TR. Pre-press and design by Tony Hadland E-mail: [email protected] Printed by Antony Rowe Limited, 2 Whittle Drive, Highfield Industrial Estate, Eastbourne, East Sussex, BN23 6QT. E-mail: [email protected] While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, neither the author nor the publisher can be held responsible for any loss or inconvenience arising from errors contained in this work. Feedback from readers on points of accuracy will be welcomed and should be e-mailed to [email protected] or mailed to the author via the publisher. Front cover: Mapledurham House, front elevation. Back cover: Mapledurham House, as seen from the Thames. A high gable end, clad in reflective oyster shells, indicated a safe house for Catholics. -

OXONIENSIA PRINT.Indd 253 14/11/2014 10:59 254 REVIEWS

REVIEWS Joan Dils and Margaret Yates (eds.), An Historical Atlas of Berkshire, 2nd edition (Berkshire Record Society), 2012. Pp. xii + 174. 164 maps, 31 colour and 9 b&w illustrations. Paperback. £20 (plus £4 p&p in UK). ISBN 0-9548716-9-3. Available from: Berkshire Record Society, c/o Berkshire Record Offi ce, 9 Coley Avenue, Reading, Berkshire, RG1 6AF. During the past twenty years the historical atlas has become a popular means through which to examine a county’s history. In 1998 Berkshire inspired one of the earlier examples – predating Oxfordshire by over a decade – when Joan Dils edited an attractive volume for the Berkshire Record Society. Oxoniensia’s review in 1999 (vol. 64, pp. 307–8) welcomed the Berkshire atlas and expressed the hope that it would sell out quickly so that ‘the editor’s skills can be even more generously deployed in a second edition’. Perhaps this journal should modestly refrain from claiming credit, but the wish has been fulfi lled and a second edition has now appeared. Th e new edition, again published by the Berkshire Record Society and edited by Joan Dils and Margaret Yates, improves upon its predecessor in almost every way. Advances in digital technology have enabled the new edition to use several colours on the maps, and this helps enormously to reveal patterns and distributions. As before, the volume has benefi ted greatly from the design skills of the Department of Typography and Graphic Communication at the University of Reading. Some entries are now enlivened with colour illustrations as well (for example, funerary monuments, local brickwork, a workhouse), which enhance the text, though readers could probably have been left to imagine a fl ock of sheep grazing on the Downs. -

Post-Medieval and Modern Resource Assessment

THE SOLENT THAMES RESEARCH FRAMEWORK RESOURCE ASSESSMENT POST-MEDIEVAL AND MODERN PERIOD (AD 1540 - ) Jill Hind April 2010 (County contributions by Vicky Basford, Owen Cambridge, Brian Giggins, David Green, David Hopkins, John Rhodes, and Chris Welch; palaeoenvironmental contribution by Mike Allen) Introduction The period from 1540 to the present encompasses a vast amount of change to society, stretching as it does from the end of the feudal medieval system to a multi-cultural, globally oriented state, which increasingly depends on the use of Information Technology. This transition has been punctuated by the protestant reformation of the 16th century, conflicts over religion and power structure, including regicide in the 17th century, the Industrial and Agricultural revolutions of the 18th and early 19th century and a series of major wars. Although land battles have not taken place on British soil since the 18th century, setting aside terrorism, civilians have become increasingly involved in these wars. The period has also seen the development of capitalism, with Britain leading the Industrial Revolution and becoming a major trading nation. Trade was followed by colonisation and by the second half of the 19th century the British Empire included vast areas across the world, despite the independence of the United States in 1783. The second half of the 20th century saw the end of imperialism. London became a centre of global importance as a result of trade and empire, but has maintained its status as a financial centre. The Solent Thames region generally is prosperous, benefiting from relative proximity to London and good communications routes. The Isle of Wight has its own particular issues, but has never been completely isolated from major events. -

09/00768/F Ward: Yarnton, Gosford and Water Eaton Date Valid

Application No: Ward: Yarnton, Date Valid: 18 09/00768/F Gosford and Water August 2009 Eaton Applicant: MHJ Ltd and Couling Holdings Site OS Parcel 9875 Adjoining Oxford Canal and North of The Gables, Address: Woodstock Road, Yarnton Proposal: Proposed 97 berth canal boat basin with facilities building; mooring pontoons; service bollards; fuel; pump out; 2 residential managers moorings; entrance structure with two-path bridge, facilities building with WC’s shower and office; 48 car parking spaces and landscaping. 1. Site Description and Proposal 1.1 The application site is located to the south east of Yarnton and south west of Kidlington. It is situated and accessed to the north of the A44, adjacent to the western side of the Oxford Canal. The access runs through the existing industrial buildings located at The Gables and the site is to the north of these buildings. 1.2 The site has a total area of 2.59 hectares and consists of low lying, relatively flat, agricultural land. There are a number of trees and hedgerows that identify the boundary of the site. 1.3 The site is within the Oxford Green Belt, it is adjacent to a classified road and the public tow path, it is within the flood plain, contains BAP Priority Habitats, is part of a proposed Local Wildlife Site and is within 2km of SSSI’s. 1.4 The application consists of the elements set out above in the ‘proposal’. It is not intended that, other than the manager’s moorings, these moorings be used for residential purposes. The submission is supported by an Environmental Statement, Supporting Statement and a Design and Access Statement. -

Epwell Grounds Farm 13/01600/F Shutford Road Epwell OX15 6HF

Epwell Grounds Farm 13/01600/F Shutford Road Epwell OX15 6HF Ward: Sibford District Councillor: Cllr. Reynolds Case Officer: Rebekah Morgan Recommendation: Approve Applicant: Mr Bart Dalla Mura Application Description: Solar Park Committee Referral : Major application Committee Date: 9 January 2014 1. Site Description and Proposal 1.1 The site is an area of farmland adjacent to Epwell Grounds Farm complex, which lies to the north of Epwell Road, approximately 950m to the south of the village of Shenington, 1.2km to the north-west of the village of Shutford and 850m to the west of The Plain Road. 1.2 The topography of the wider landscape is varied, scattered with a number of small hills. To the north-west of Shenington village is Shenington gliding club and airfield (1.2km from the site). 1.3 The site is made up of a single field currently under arable production with existing hedgerows along the boundaries. A public right of way is immediately adjacent to the site following the northern and eastern boundaries. 1.4 The proposal seeks consent for the construction of a solar park, to include the installation of solar panels to generate up to 7MW of electricity, with control room, fencing and other associated works. The application boundary measures 15.07 hectares; the number of individual panels has not been specified. 2. Application Publicity 2.1 The application has been advertised by way of a press notice, site notice and neighbour letters. The final date for comment on this application was 24th December 2013. One letter was received raising the following concerns: • Visual impact, being such a large site 3. -

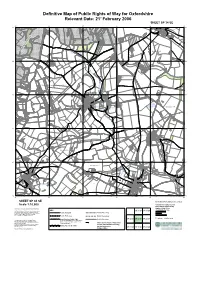

Definitive Map of Public Rights of Way for Oxfordshire Relevant Date: 21 February 2006

Definitive Map of Public Rights of Way for Oxfordshire Relevant Date: 21st February 2006 Colour SHEET SP 34 SE 35 36 37 38 39 40 255/2 1400 5600 0006 8000 0003 2500 4900 6900 0006 0006 5600 7300 0004 0004 2100 3300 4500 7500 1900 4600 6600 6800 A 422 0003 5000 0006 1400 2700 5600 7300 0004 0004 2100 3300 4500 5600 7500 0006 1900 4600 6600 6800 8000 0003 8000 2700 PAGES LANE Church CHURCH LANE Apple The The Yews Cottage 45 Berries 45 Westlynne West View Spring Lime Tree Cott School Cottage Rose Cottage255/2 255/11 Malahide The Pudlicote Cottage Field View Dun Cow 3993 WEST END 3993 Manor 255/6a Canada (PH) Cromwell Cottage House The 8891 8891 Cottage THE GREEN HORNTON 0991 Reservoir 25 (disused) 5/2a 3291 255/3 Pond Stable Cott 1087 1087 Foxbury Barn Foxbury Barn 1787 0087 0087 Sugarswell Farm Issues 2784 Sugarswell Farm 5885 2784 5885 The Nook 8684 8684 Holloway Drain House Hall 9083 9083 255/5 Rose BELL STREET Cottage Old Lodge FarmOld Lodge Farm Pricilla House Turncott 3882 Home Farm 3882 3081 3081 Old Post Cottage 2080 2080 Bellvue Water Orchard Cottage ndrush Walnut Bank Wi Pavilion Brae House 0479 0479 2979 Issues 1477 1477 Sheraton Upper fton Reaches Rise Gra Roseglen 0175 0175 ilee House Langway Jub Pond Tourney House 255/4 Drain Issues 255/2a Spring 3670 3670 Drain 5070 Temple Pool 2467 Hall 2467 82668266 Spring Spring 2765 43644364 5763 7463 3263 5763 7463 3263 255/3 0062 0062 0062 0062 Reservoir 7962 Issues (Disused) Issues Pond Spring 4359 4359 1958 1958 8457 0857 8457 0857 6656 6656 4756 7554 3753 2353 5453 3753 2353 5453 -

General Information Notes and Symbols

General Information Notes and Symbols This timetable includes all Chiltern Railways services On Mondays to Fridays you can also use most of There are no restrictions on folding bikes at any GW Great Western Railway between Banbury, Kings Sutton, Bicester North, our trains, with the exception of our busiest peak time, provided they are fully folded. For information t Trains with tables and power points Bicester Village, Haddenham & Thame Parkway and hour services. For the safety and comfort of all our about cycle storage facilities at our stations see our ; Hybrid train comprised of both silver and London Marylebone. Great Western Railway services passengers bikes are not allowed at any point during website. commuter carriages between Banbury and Kings Sutton are also included. the journey on any train: / Silver train including Business Zone carriage Other services also run between Banbury, Cycles can be hired from just outside a Bicycles are not permitted on board at any point Kings Sutton and Bicester Village (via Oxford) to • Arriving at London Marylebone, Oxford or London Marylebone station. For information visit during this service London Paddington. Birmingham Moor Street from 0745 to 1000. www.tfl.gov.uk/modes/cycling/santander-cycles. e Continued in later column • Leaving London Marylebone, Oxford or f Continued from earlier column Off-Peak Travel Birmingham Moor Street from 1630 to 1930. Safety Information a Arrival time h First train to London available for holders of Off- • Non-folding bicycles are not permitted for In almost all emergency situations it is safest to stay b Departure time only. Change at Banbury for the Peak Day Return, Off-Peak Return, Off-Peak and Day any part of the journey on the train that leaves on the train and then listen for instructions from a connecting service departing at 0724 Travelcards (includes unlimited travel on London’s Bicester North at 0623 on weekday mornings, member of staff. -

Job 124253 Type

A SPLENDID GRADE II LISTED FAMILY HOUSE WITH 4 BEDROOMS, IN PRETTY ISLIP Greystones, Middle Street, Islip, Oxfordshire OX5 2SF Period character features throughout with an impressive modern extension and attractive gardens Greystones, Middle Street, Islip, Oxfordshire OX5 2SF 2 reception rooms ◆ kitchen/breakfast/family room ◆ utility ◆ cloakroom ◆ master bedroom with walk-in wardrobe and en suite shower room ◆ 3 additional bedrooms ◆ play room ◆ 2 bathrooms ◆ double garage ◆ gardens ◆ EPC rating = Listed Building Situation Islip mainline station 0.2 miles (52 minutes to London Marylebone), Kidlington 2.5 miles, M40 (Jct 9) 4.2 miles, Oxford city centre 4.5 miles Islip is a peaceful and picturesque village, conveniently located just four miles from Oxford and surrounded by beautiful Oxfordshire countryside. The village has two pubs, a doctor’s surgery and a primary school. The larger nearby village of Kidlington offers a wide range of shops, supermarkets and both primary and secondary schools. A further range of excellent schools can also be found in Oxford, along with first class shopping, leisure and cultural facilities. Directions From Savills Summertown office head north on Banbury Road for two miles (heading straight on at one roundabout) and then at the roundabout, take the fourth exit onto Bicester Road. After approximately a mile and a quarter, at the roundabout, take the second exit and continue until you arrive in Islip. Turn right at the junction onto Bletchingdon Road. Continue through the village, passing the Red Lion pub, and you will find the property on your left-hand side, on the corner of Middle Street.