NBA Salaries: Assessing True Player Value

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

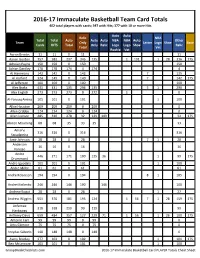

2016-17 Immaculate Basketball Player Checklist;

2016-17 Immaculate Basketball Team Card Totals 402 total players with cards; 397 with Hits; 377 with 10 or more Hits Auto Auto Relic NBA Total Total Auto Auto Auto NBA NBA Auto Other Team Only Letter Logo Shoe Base Cards HITS Total Only Relic Logo Logo Shoe Relic Total Vet Rookie Vet Aaron Brooks 11 11 0 11 11 Aaron Gordon 757 582 237 345 135 1 101 1 28 316 175 Adreian Payne 150 150 0 150 150 Adrian Dantley 178 178 174 4 174 4 AJ Hammons 142 142 0 142 7 135 Al Horford 324 149 0 149 7 142 175 Al Jefferson 100 100 0 100 100 Alec Burks 431 431 135 296 135 5 1 290 Alex English 273 273 273 0 272 1 0 Al-Farouq Aminu 101 101 0 101 1 100 Allan Houston 209 209 209 0 209 0 Allen Crabbe 124 124 124 0 124 0 Allen Iverson 485 310 278 32 129 149 32 175 Alonzo Mourning 68 68 35 33 35 33 Amar'e 316 316 0 316 316 Stoudemire Amir Johnson 28 28 0 28 7 1 20 Anderson 16 16 0 16 16 Varejao Andre 446 271 171 100 135 36 1 99 175 Drummond Andre Iguodala 101 101 0 101 1 100 Andre Miller 61 61 0 61 61 Andre Roberson 194 194 0 194 8 1 185 Andrei Kirilenko 246 246 146 100 146 100 Andrew Bogut 28 28 0 28 1 27 Andrew Wiggins 551 376 181 195 124 1 56 7 1 28 159 175 Anfernee 318 318 219 99 219 99 Hardaway Anthony Davis 659 484 357 127 229 71 1 56 1 26 100 175 Antoine Carr 99 99 99 0 99 0 Artis Gilmore 75 75 75 0 75 0 Arvydas Sabonis 148 148 148 0 148 0 Avery Bradley 277 102 0 102 1 101 175 Ben McLemore 101 101 0 101 1 100 GroupBreakChecklists.com 2016-17 Immaculate Basketball Card PLAYER Totals Cheat Sheet Auto Auto Relic NBA Total Total Auto Auto Auto NBA NBA Auto Other -

Mississippi State 2020-21 Basketball

11 NCAA TOURNAMENT APPEARANCES 1963 • 1991 • 1995 • 1996 • 2002 • 2003 MISSISSIPPI STATE 2004 • 2005 • 2008 • 2009 • 2019 MEN’S BASKETBALL CONTACT 2020-21 BASKETBALL MATT DUNAWAY • [email protected] OFFICE (662) 325-3595 • CELL (727) 215-3857 Mississippi State (14-12 • 8-9 SEC) vs. Auburn (12-14 • 6-11 SEC) GAME 27 • AUBURN ARENA • AUBURN, ALABAMA • SATURDAY, MARCH 6 • 12:00 P.M. CT 27 TV: SEC NETWORK • WATCH ESPN APP • RADIO: 100.9 WKBB-FM • STARKVILLE • ONLINE: HAILSTATE.COM • TUNE-IN RADIO APP MISSISSIPPI STATE (14-12 • 8-9 SEC) MISSISSIPPI STATE POSSIBLE STARTING LINEUP • BASED ON PREVIOUS GAMES H: 9-6 • A: 5-3 • N: 0-3 • OT: 0-2 NO. 1 IVERSON MOLINAR • G • 6-3 • 190 • SO. • PANAMA CITY, PANAMA NOVEMBER • 1-2 2020-21 • 16.3 PPG • 140-297 FG • 32-71 3-PT FG • 64-80 FT • 3.9 RPG • 2.6 APG • 1.1 SPG Space Coast Challenge • Melbourne, Florida • Nov. 25-26 Wed. 25 vs. Clemson • CBS-SN L • 53-42 LAST GAME • AT TEXAS A&M • 18 PTS • 7-12 FG • 2-5 3-PT FG • 2-4 FT • 5 REB • 3 ASST • 1 STL Thur. 26 vs. Liberty • CBS-SN L • 84-73 • Molinar is an explosive combo guard who is a talented shooter, passer and slasher that can get to the rim • 16.3 PPG is 6th in the SEC (03/06) Mon. 30 Texas State • SECN W • 68-51 • Dialed up career-high 24 PTS at UGA (12/30) and at VANDY (01/09) • Howland: Molinar’s jump from FR/SOPH reminds him of Russell Westbrook at UCLA DECEMBER • 5-1 • 10+ PTS in 20 of his 23 outings and 6 GMS of 20+ PTS in 2020-21 • His +10.4 PPG is T-8th largest FR/SOPH scoring jump in SEC over last decade Fri. -

Panini America Redemption Report November 9Th 2015

SET INSERT/SUBSET # PLAYER 2014 Panini Court Kings (14-15) Basketball Impressionist Ink 9 Anthony Davis 2014 Panini Court Kings (14-15) Basketball Impressionist Ink Sapphire 9 Anthony Davis 2014 Panini Paramount (14-15) Basketball Penmanship 8 Anthony Davis 2014 Panini Totally Certified (14-15) Basketball Certified Competitor Autographs 2 Anthony Davis 2014 Panini Totally Certified (14-15) Basketball Mirror Certified Competitor Autographs 2 Anthony Davis 2013 Panini Court Kings (13-14) Basketball Court Kings Autographs 38 Alexey Shved 2013 Panini Court Kings (13-14) Basketball Court Kings Autographs Gold 6 Andre Iguodala 2013 Panini Court Kings (13-14) Basketball Court Kings Autographs Gold 38 Alexey Shved 2013 Panini Elite (13-14) Basketball Turn of the Century Signatures 75 Blake Griffin 2013 Panini Gold Standard (13-14) Basketball Rookie Autographs 244 Andre Roberson 2013 Panini Gold Standard (13-14) Basketball Rookie Autographs Platinum 244 Andre Roberson 2013 Panini Immaculate Collection (13-14) Basketball Patches Autographs 155 Alonzo Mourning 2013 Panini National Treasures (13-14) Basketball Rookie Patch Autographs 117 Alex Len 2013 Panini Preferred (13-14) Basketball Silhouettes 352 Blake Griffin 2013 Panini Prizm (13-14) Basketball Autographs 62 Blake Griffin 2013 Panini Select (13-14) Basketball Franchise Signatures Prizms Blue 7 Allan Houston 2013 Panini Select (13-14) Basketball Franchise Signatures Prizms Gold 7 Allan Houston 2013 Panini Select (13-14) Basketball Franchise Signatures Prizms Purple 7 Allan Houston 2013 Panini Select (13-14) Basketball Signatures 34 B.J. Armstrong 2013 Panini Select (13-14) Basketball Signatures Prizms Blue 34 B.J. Armstrong 2013 Panini Select (13-14) Basketball Signatures Prizms Purple 34 B.J. -

Numbers Game -- the Washington Times the Washington Times

Numbers game -- The Washington Times The Washington Times www.washingtontimes.com Numbers game By Patrick Hruby THE WASHINGTON TIMES Published April 13, 2004 Everyone else has it wrong. The fans. The press. Even the league. They're blinded by box scores. Hamstrung by hype. Of this and more, Wayne Winston is certain. A single mouse click tells him so. "Nobody should be talking about LeBron James and Carmelo Anthony," he says. "They should be talking about Dwyane Wade. It's a crime." For Winston, Wade's superiority is not a matter of opinion. It's a fact, cold and hard, like an icicle. You can argue politics, and you can argue the best "Godfather" flick (well, excluding part III). But when it comes to the NBA Rookie of the Year race, you can't argue the data. At least not with Winston, a former "Jeopardy" champ who's good with math the way Eric Clapton is good with chords. "James rates as an average NBA player," says Winston, a professor of decision sciences at Indiana University. "That's good since very few rookies rate that high. But Wade's a real impact player for Miami. He ranks 21st best in the league in terms of changing the chances of your team winning a game." Like any MIT graduate worth his sodium chloride, Winston has the numbers to prove his point. More than 5,000 pages' worth, to be exact. Only you won't find his statistics in a newspaper. Together with fellow sports math guru Jeff Sagarin -- the brain behind USA Today's computer rankings -- Winston has created Winval, a sophisticated program that rates and ranks the value of every NBA player from Tariq Abdul-Wahad to Lorenzen Wright. -

The Total Person Graduating Every Men’S Basketball Senior Since 1986

THE TOTAL PERSON GRADUATING EVERY MEN’S BASKETBALL SENIOR SINCE 1986 Xavier University has earned a reputation for student-athlete academic success. Every senior student-athlete in the men’s basketball program, including Matt Stainbrook (seen here at his graduation with Xavier University President Michael J. Graham, S.J.), has graduated for the last 30 school years. That streak began in the 1985-86 school year. Xavier makes a promise to each student it recruits. That’s a promise XU keeps and celebrates every May at graduation. 4 PLAYERS WHO COMPLETED THEIR % THAT XAVIER’S GRADUATION STREAK ELIGIBILITY GRADUATED 1986 6 100% 1987 NO SENIORS 1988 4 100% 1989 2 100% 1990 4 100% 1991 3 100% 1992 NO SENIORS 1993 6 100% 1994 4 100% 1995 5 100% 1996 1 100% 1997 4 100% 1998 4 100% 1999 4 100% 2000 1 100% 2001 3 100% 2002 3 100% 2003 3 100% 2004 3 100% 2005 1 100% 2006 5 100% 2007 4 100% 2008 3 100% 2009 3 100% 2010 1 100% 2011 6 100% 2012 5 100% 2013 3 100% 2014 3 100% 2015 2 100% SINCE 1986 96 100% SISTER ROSE ANN FLEMING XAVIER ATHLETIC HALL OF FAMER Since she became Xavier’s academic advisor in 1985, Sr. Rose Ann Fleming (seen here with 2010 graduate Jason Love) has helped every men’s basketball player who has reached his final year of athletic eligibility to graduate. A book has been written about her, “Out of Habit.” Last season her “retired jersey” banner was hung at Cintas Center. -

Crushing Loss the High Number of Fouls the Bears Shot Just 16 Free Throws

NFLScoRFS NBAScoRFS Pittsburgh 34, Denver 17 Denver 89, San Antonio 85 SeatLle 34, Carolina 14 Philadelphia 86, Minnesota 84 Deb'oit 99, HOWJton 97 6 The Mirror Edjtoc Nate Taylor Monday. Tau. 23. 2006 Fifth win in a row for surging Nuggets Associat ed Press Duncan effectively and pushed the good at 69·68 with 10:44 left when the perimeter, going 4·for·23 (17 get into any kind of rhythm. " ball hard against the Spurs in transi· Boykins made a short jumper after a percent) on 3-pointers. Denver also The Nuggets extended their lead TIred of getting pushed around tion. steal by Greg Buckner. It was the first ran on them effectively, scoring 32 to 79-73 before San Antonio made a by the San Antonio Spurs, the '"Ibeywere just fed up with play· of six turnovers in the period for the points on fast breaks. pair of free throws and Nick Van Denver Nuggets finally pushed back ing so many close games against Spurs, matching their number of ''You have to make shots to win Exel hit a Ooater in the lane to make S.mday. (the Spurs) and not winning" Karl field goals. basketball games and we didn't do it 79-77 with 3:37 remaining Earl Boykins scored nine of his said. "A lot of times San Antonio San Antonio committed 17 tha," Spurs coach Gregg Popovich Frandsco Elson then had a dunk 19 points in the folUth quaner, and plays with such quickness and pen· turnovers, 12 in the second half. said "You also have to get back on and BoyIdns a layup te> restore the the Nuggets held Tim Duncan to etration that you don't get a physical Duncan had a team-high six defense. -

123010 Weekly-Release.Indd

2010-11 Men’s Basketball University of Washington Athletic Communications • Box 354070 • Graves Hall • Seattle, WA 98195 • (206) 543-2230 • (206) 543-5000 fax SID Contact: Brian Tom ([email protected]) www.GoHuskies.com Weekly Release Dec. 30, 2010 Washington Huskies UW Put Record 5-Game Road Following Husky Hoops 2010-11 Record: 9-3 overall, 1-0 Pac-10 Pac-10 Win Streak On Line Radio: Washington ISP Radio Network Time / Washington and UCLA (9-4, 1-0) play Dec. 31 at 1:00 p.m. (Bob Rondeau and Jason Hamilton) Date Opponent Result Score Huskies Riding High Internet: www.GoHuskies.com N. 6 St. Martin’s (Exh) W 97-76 Washington (9-3, 1-0), winners of a team-record fi ve-straight Pac- Tickets: www.ticketmaster.com N. 13 McNeese State (18) W 118-64 10 road games and eight-straight overall against conference op- UW Basketball on Facebook: N. 16 Eastern Washington (17) W 98-72 ponents, goes for a road sweep in Los Angeles at UCLA’s Pauley http://www.facebook.com/UWMensBasketball N. 22 ^vs. Virginia (13) W 106-63 Pavilion on Friday, Dec. 31 at 1:00 p.m. (FSN-TV). The task ahead for Twitter: N. 23 ^vs. #8 Kentucky (13) L 74-67 the Huskies is daunting. UW has previously swept the L.A. schools http://twitter.com/UWSportsNews N. 24 ^vs. #2 Michigan State (13) L 76-71 only twice -- 2006 and 1987. The last time UW swept a two-game N. 30 Long Beach State (23) W 102-75 Pac-10 road series to start a season was in 1976 when they won Upcoming Games D. -

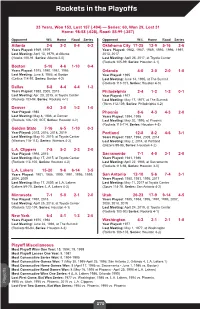

Rockets in the Playoffs

Rockets in the Playoffs 33 Years, Won 153, Lost 157 (.494) — Series: 60, Won 29, Lost 31 Home: 98-58 (.628), Road: 55-99 (.357) Opponent W-L Home Road Series Opponent W-L Home Road Series Atlanta 2-6 2-2 0-4 0-2 Oklahoma City 17-25 12-9 5-16 2-6 Years Played: 1969, 1979 Years Played: 1982, 1987, 1989, 1993, 1996, 1997, Last Meeting: April 13, 1979, at Atlanta 2013, 2017 (Hawks 100-91, Series: Atlanta 2-0) Last Meeting: April 25, 2017, at Toyota Center (Rockets 105-99, Series: Houston 4-1) Boston 5-16 4-6 1-10 0-4 Years Played: 1975, 1980, 1981, 1986 Orlando 4-0 2-0 2-0 1-0 Last Meeting: June 8, 1986, at Boston Year Played: 1995 (Celtics 114-97, Series: Boston 4-2) Last Meeting: June 14, 1995, at The Summit (Rockets 113-101, Series: Houston 4-0) Dallas 8-8 4-4 4-4 1-2 Years Played: 1988, 2005, 2015 Philadelphia 2-4 1-2 1-2 0-1 Last Meeting: Apr. 28, 2015, at Toyota Center Year Played: 1977 (Rockets 103-94, Series: Rockets 4-1) Last Meeting: May 17, 1977, at The Summit (76ers 112-109, Series: Philadelphia 4-2) Denver 4-2 3-0 1-2 1-0 Year Played: 1986 Phoenix 8-6 4-3 4-3 2-0 Last Meeting: May 8, 1986, at Denver Years Played: 1994, 1995 (Rockets 126-122, 2OT, Series: Houston 4-2) Last Meeting: May 20, 1995, at Phoenix (Rockets 115-114, Series: Houston 4-3) Golden State 7-16 6-5 1-10 0-3 Year Played: 2015, 2016, 2018, 2019 Portland 12-8 8-2 4-6 3-1 Last Meeting: May 10, 2019, at Toyota Center Years Played: 1987, 1994, 2009, 2014 (Warriors 118-113), Series: Warriors 4-2) Last Meeting: May 2, 2014, at Portland (Blazers 99-98, Series: Houston 4-2) L.A. -

Player Set Card # Team Print Run Al Horford Top-Notch Autographs

2013-14 Innovation Basketball Player Set Card # Team Print Run Al Horford Top-Notch Autographs 60 Atlanta Hawks 10 Al Horford Top-Notch Autographs Gold 60 Atlanta Hawks 5 DeMarre Carroll Top-Notch Autographs 88 Atlanta Hawks 325 DeMarre Carroll Top-Notch Autographs Gold 88 Atlanta Hawks 25 Dennis Schroder Main Exhibit Signatures Rookies 23 Atlanta Hawks 199 Dennis Schroder Rookie Jumbo Jerseys 25 Atlanta Hawks 199 Dennis Schroder Rookie Jumbo Jerseys Prime 25 Atlanta Hawks 25 Jeff Teague Digs and Sigs 4 Atlanta Hawks 15 Jeff Teague Digs and Sigs Prime 4 Atlanta Hawks 10 Jeff Teague Foundations Ink 56 Atlanta Hawks 10 Jeff Teague Foundations Ink Gold 56 Atlanta Hawks 5 Kevin Willis Game Jerseys Autographs 1 Atlanta Hawks 35 Kevin Willis Game Jerseys Autographs Prime 1 Atlanta Hawks 10 Kevin Willis Top-Notch Autographs 4 Atlanta Hawks 25 Kevin Willis Top-Notch Autographs Gold 4 Atlanta Hawks 10 Kyle Korver Digs and Sigs 10 Atlanta Hawks 15 Kyle Korver Digs and Sigs Prime 10 Atlanta Hawks 10 Kyle Korver Foundations Ink 23 Atlanta Hawks 10 Kyle Korver Foundations Ink Gold 23 Atlanta Hawks 5 Pero Antic Main Exhibit Signatures Rookies 43 Atlanta Hawks 299 Spud Webb Main Exhibit Signatures 2 Atlanta Hawks 75 Steve Smith Game Jerseys Autographs 3 Atlanta Hawks 199 Steve Smith Game Jerseys Autographs Prime 3 Atlanta Hawks 25 Steve Smith Top-Notch Autographs 31 Atlanta Hawks 325 Steve Smith Top-Notch Autographs Gold 31 Atlanta Hawks 25 groupbreakchecklists.com 13/14 Innovation Basketball Player Set Card # Team Print Run Bill Sharman Top-Notch Autographs -

Rosters Set for 2014-15 Nba Regular Season

ROSTERS SET FOR 2014-15 NBA REGULAR SEASON NEW YORK, Oct. 27, 2014 – Following are the opening day rosters for Kia NBA Tip-Off ‘14. The season begins Tuesday with three games: ATLANTA BOSTON BROOKLYN CHARLOTTE CHICAGO Pero Antic Brandon Bass Alan Anderson Bismack Biyombo Cameron Bairstow Kent Bazemore Avery Bradley Bojan Bogdanovic PJ Hairston Aaron Brooks DeMarre Carroll Jeff Green Kevin Garnett Gerald Henderson Mike Dunleavy Al Horford Kelly Olynyk Jorge Gutierrez Al Jefferson Pau Gasol John Jenkins Phil Pressey Jarrett Jack Michael Kidd-Gilchrist Taj Gibson Shelvin Mack Rajon Rondo Joe Johnson Jason Maxiell Kirk Hinrich Paul Millsap Marcus Smart Jerome Jordan Gary Neal Doug McDermott Mike Muscala Jared Sullinger Sergey Karasev Jannero Pargo Nikola Mirotic Adreian Payne Marcus Thornton Andrei Kirilenko Brian Roberts Nazr Mohammed Dennis Schroder Evan Turner Brook Lopez Lance Stephenson E'Twaun Moore Mike Scott Gerald Wallace Mason Plumlee Kemba Walker Joakim Noah Thabo Sefolosha James Young Mirza Teletovic Marvin Williams Derrick Rose Jeff Teague Tyler Zeller Deron Williams Cody Zeller Tony Snell INACTIVE LIST Elton Brand Vitor Faverani Markel Brown Jeffery Taylor Jimmy Butler Kyle Korver Dwight Powell Cory Jefferson Noah Vonleh CLEVELAND DALLAS DENVER DETROIT GOLDEN STATE Matthew Dellavedova Al-Farouq Aminu Arron Afflalo Joel Anthony Leandro Barbosa Joe Harris Tyson Chandler Darrell Arthur D.J. Augustin Harrison Barnes Brendan Haywood Jae Crowder Wilson Chandler Caron Butler Andrew Bogut Kentavious Caldwell- Kyrie Irving Monta Ellis -

USA Basketball Men's Pan American Games Media Guide Table Of

2015 Men’s Pan American Games Team Training Camp Media Guide Colorado Springs, Colorado • July 7-12, 2015 2015 USA Men’s Pan American Games 2015 USA Men’s Pan American Games Team Training Schedule Team Training Camp Staffing Tuesday, July 7 5-7 p.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II 2015 USA Pan American Games Team Staff Head Coach: Mark Few, Gonzaga University July 8 Assistant Coach: Tad Boyle, University of Colorado 9-11 a.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II Assistant Coach: Mike Brown 5-7 p.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II Athletic Trainer: Rawley Klingsmith, University of Colorado Team Physician: Steve Foley, Samford Health July 9 8:30-10 a.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II 2015 USA Pan American Games 5-7 p.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II Training Camp Court Coaches Jason Flanigan, Holmes Community College (Miss.) July 10 Ron Hunter, Georgia State University 9-11 a.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II Mark Turgeon, University of Maryland 5-7 p.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II July 11 2015 USA Pan American Games 9-11 a.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II Training Camp Support Staff 5-7 p.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II Michael Brooks, University of Louisville July 12 Julian Mills, Colorado Springs, Colorado 9-11 a.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II Will Thoni, Davidson College 5-7 p.m. MDT Practice at USOTC Sports Center II USA Men’s Junior National Team Committee July 13 Chair: Jim Boeheim, Syracuse University NCAA Appointee: Bob McKillop, Davidson College 6-8 p.m. -

Springfield Springfield

Springfield Franconia ❖ Kingstowne ❖ Newington European Classified, Page 17 Classified, Taste Treats ❖ News, Page 3 Fall for Sports, Page 13 ❖ Fairfax Fall Fun, Page 12 Calendar, Page 8 Mums and pumpkins decorated last weekend’s Fall for Fairfax Festival at the Fairfax County Government Center. ChristianChristian ClubClub ThrivesThrives atat LeeLee News,News, PagePage 33 PERMIT #86 PERMIT Martinsburg, WV Martinsburg, PAID U.S. Postage U.S. PRSRT STD PRSRT Photo by Deb Cobb/The Connection www.ConnectionNewspapers.comOctober 7-13, 2010 ❖ Volume XXIV, Number 40 online at www.connectionnewspapers.comSpringfield Connection ❖ October 7-13, 2010 ❖ 1 th Presents Our 16 Annual DAILY 9AM–9PM SPOOKY HAY RIDES • MONEY MOUNTAIN MINERS MOUNTAIN SLIDE FALL FESTIVAL WIZARD OF OZ SLIDE W/ADDITIONAL SLIDE • MINI CAROUSEL & Pumpkin Playground WESTERN TOWN • GRAVE YARD AIRPLANE • MERRY-GO-ROUNDS INDIAN TEE-PEE • TUMBLING TUBES October 1 PHONE TUBES • GHOST TUNNEL thru October 31 SLIDE PUMPKIN FORT • FARM ANIMALS • MECHANICAL RIDES Fall is a great time to plant. Visit PIRATE SHIP AND PIRATES CAMP our Nursery for trees, shrubs and GHOST TRAIN • SPOOKY CASTLE all your garden needs! FIRETRUCK• MONSTER TRUCK SLIDE For More Information Call: SPECIAL EVENTS (703) 323-1188 SAT - SUN 10–5 www.pumpkinplayground.com INFLATABLE FUN CENTERS FACE PAINTING Additional Fees for these Events: CRAWL MAZE $1 BALLOON ANIMALS $2 9401 Burke Road WOBBLE WAGON $2 Burke, VA 22015 MOON BOUNCE $2 PONY RIDES $5 GIGANTIC Featuring SELECTION OF MARY APONTE PUMPKINS • CORN STALKS Cherokee CIDER • JAMS & JELLIES Story Teller APPLES • HALLOWEEN DECORATIONS Weekdays CABBAGE & KALE • WINTER PANSIES CHRYSANTHEMUMS DAILY 9 - 9 • ADMISSION $9.00 M-F; $12.00 SAT/SUN & Oct.