An Examination of Executive Development Programs in Private Illinois Colleges and Universities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HEERF Total Funding by Institution

Higher Education Emergency Relief Fund Allocations to Institutions as Authorized by Section 18004 of the CARES Act Sec. 18004(a)(1) Sec. 18004(a)(2) Sec. 18004(a)(3) Institution State School Type Total Allocation (90%) (7.5%) (2.5%) Alaska Bible College AK Private-Nonprofit $42,068 $457,932 $500,000 Alaska Career College AK Proprietary 941,040 941,040 Alaska Christian College AK Private-Nonprofit 201,678 211,047 87,275 500,000 Alaska Pacific University AK Private-Nonprofit 254,627 253,832 508,459 Alaska Vocational Technical Center AK Public 71,437 428,563 500,000 Ilisagvik College AK Public 36,806 202,418 260,776 500,000 University Of Alaska Anchorage AK Public 5,445,184 272,776 5,717,960 University Of Alaska Fairbanks AK Public 2,066,651 1,999,637 4,066,288 University Of Alaska Southeast AK Public 372,939 354,391 727,330 Totals: Alaska $9,432,430 $3,294,101 $1,234,546 $13,961,077 Alabama Agricultural & Mechanical University AL Public $9,121,201 $17,321,327 $26,442,528 Alabama College Of Osteopathic Medicine AL Private-Nonprofit 3,070 496,930 500,000 Alabama School Of Nail Technology & Cosmetology AL Proprietary 77,735 77,735 Alabama State College Of Barber Styling AL Proprietary 28,259 28,259 Alabama State University AL Public 6,284,463 12,226,904 18,511,367 Athens State University AL Public 845,033 41,255 886,288 Auburn University AL Public 15,645,745 15,645,745 Auburn University Montgomery AL Public 5,075,473 333,817 5,409,290 Bevill State Community College AL Public 2,642,839 129,274 2,772,113 Birmingham-Southern College AL Private-Nonprofit -

College Name Adrian College Advocate Illinois Masonic Medical

College Name Adrian College Advocate Illinois Masonic Medical Center Albion College Alverno College American Academy of Art Aquinas College Argosy University Ashford University Augustana College Aurora University Ball State University Barry University Beloit College Benedictine University Blackburn College Bradley University Briar Cliff University Butler University Cardinal Stritch University Carleton College Carroll College Carthage College Catholic University of America Central Michigan University Chamberlain Col of Nursing Chicago State University Christian Brothers University Clarke College Coe College Colorado College Colorado State University College of St. Benedict & St. John's University College of St. Catherine Columbia College of Chicago Concorida University Cooking & Hospitality Institute Cornell College Coyne American Institute Creighton University Culver Stockton College DePaul University DePauw University DeVry University Dominican University Drake University Drury University East-West University Eastern Illinois University Eastern Michigan University Edgewood College Elmhurst College Embry Riddle Aeronautical University Eureka College Fairfield University The Fashion Institue of Design & Merchandising Ferris State University Grand Valley State Grinnell College Harrington College of Design Hillsdale College Holy Cross College Illinois College Illinois Institute of Art Illinois Institute of Technology Illinois State University Illinois Wesleyan University Indiana University Indiana U-Purdue U International Academy of Design -

FICE Code List for Colleges and Universities (X0011)

FICE Code List For Colleges And Universities ALABAMA ALASKA 001002 ALABAMA A & M 001061 ALASKA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY 001005 ALABAMA STATE UNIVERSITY 066659 PRINCE WILLIAM SOUND C.C. 001008 ATHENS STATE UNIVERSITY 011462 U OF ALASKA ANCHORAGE 008310 AUBURN U-MONTGOMERY 001063 U OF ALASKA FAIRBANKS 001009 AUBURN UNIVERSITY MAIN 001065 UNIV OF ALASKA SOUTHEAST 005733 BEVILL STATE C.C. 001012 BIRMINGHAM SOUTHERN COLL ARIZONA 001030 BISHOP STATE COMM COLLEGE 001081 ARIZONA STATE UNIV MAIN 001013 CALHOUN COMMUNITY COLLEGE 066935 ARIZONA STATE UNIV WEST 001007 CENTRAL ALABAMA COMM COLL 001071 ARIZONA WESTERN COLLEGE 002602 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 001072 COCHISE COLLEGE 012182 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 031004 COCONINO COUNTY COMM COLL 012308 COMM COLLEGE OF THE A.F. 008322 DEVRY UNIVERSITY 001015 ENTERPRISE STATE JR COLL 008246 DINE COLLEGE 001003 FAULKNER UNIVERSITY 008303 GATEWAY COMMUNITY COLLEGE 005699 G.WALLACE ST CC-SELMA 001076 GLENDALE COMMUNITY COLL 001017 GADSDEN STATE COMM COLL 001074 GRAND CANYON UNIVERSITY 001019 HUNTINGDON COLLEGE 001077 MESA COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001020 JACKSONVILLE STATE UNIV 011864 MOHAVE COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001021 JEFFERSON DAVIS COMM COLL 001082 NORTHERN ARIZONA UNIV 001022 JEFFERSON STATE COMM COLL 011862 NORTHLAND PIONEER COLLEGE 001023 JUDSON COLLEGE 026236 PARADISE VALLEY COMM COLL 001059 LAWSON STATE COMM COLLEGE 001078 PHOENIX COLLEGE 001026 MARION MILITARY INSTITUTE 007266 PIMA COUNTY COMMUNITY COL 001028 MILES COLLEGE 020653 PRESCOTT COLLEGE 001031 NORTHEAST ALABAMA COMM CO 021775 RIO SALADO COMMUNITY COLL 005697 NORTHWEST -

Air Force ROTC at Illinois Institute of Tech Albion College Allegheny

Air Force ROTC at Illinois Institute of Tech Colgate University Albion College College of DuPage Allegheny College College of St. Benedict and St. John's University Alverno College Colorado College American Academy of Art Colorado State University Andrews University Columbia College-Chicago Aquinas College Columbia College-Columbia Arizona State University Concordia University-Chicago Auburn University Concordia University-WI Augustana College Cornell College Aurora University Cornell University Ball State University Creighton University Baylor University Denison University Belmont University DePaul University Blackburn College DePauw University Boston College Dickinson College Bowling Green State University Dominican University Bradley University Drake University Bucknell University Drexel University Butler University Drury University Calvin College East West University Canisius College Eastern Illinois University Carleton College Eastern Michigan University Carroll University Elmhurst College Carthage College Elon University Case Western Reserve University Emmanuel College Central College Emory University Chicago State University Eureka College Clarke University Ferris State University Florida Atlantic University Lakeland University Florida Institute of Technology Lawrence Technological University Franklin College Lawrence University Furman University Lehigh University Georgia Institute of Technology Lewis University Governors State University Lincoln Christian University Grand Valley State University Lincoln College Hamilton College -

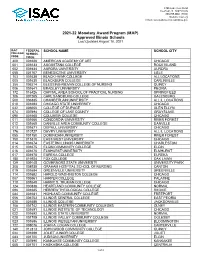

2021-22 Monetary Award Program (MAP) Approved Illinois Schools Last Updated August 16, 2021

1755 Lake Cook Road Deerfield, IL 60015-5209 800.899.ISAC (4722) Website: isac.org E-mail: [email protected] 2021-22 Monetary Award Program (MAP) Approved Illinois Schools Last Updated August 16, 2021 ISAC FEDERAL SCHOOL NAME SCHOOL CITY COLLEGE SCHOOL CODE CODE 400 001628 AMERICAN ACADEMY OF ART CHICAGO 001 001633 AUGUSTANA COLLEGE ROCK ISLAND 002 001634 AURORA UNIVERSITY AURORA 058 001767 BENEDICTINE UNIVERSITY LISLE 103 001638 BLACK HAWK COLLEGE ALL LOCATIONS 005 001639 BLACKBURN COLLEGE CARLINVILLE 358 006214 BLESSING-RIEMAN COLLEGE OF NURSING QUINCY 006 001641 BRADLEY UNIVERSITY PEORIA 172 016426 CAPITAL AREA SCHOOL OF PRACTICAL NURSING SPRINGFIELD 106 007265 CARL SANDBURG COLLEGE GALESBURG 500 006385 CHAMBERLAIN UNIVERSITY ALL IL LOCATIONS 010 001694 CHICAGO STATE UNIVERSITY CHICAGO 032 006656 COLLEGE OF DUPAGE GLEN ELLYN 074 007694 COLLEGE OF LAKE COUNTY GRAYSLAKE 090 001665 COLUMBIA COLLEGE CHICAGO 011 001666 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY RIVER FOREST 012 001669 DANVILLE AREA COMMUNITY COLLEGE DANVILLE 013 001671 DEPAUL UNIVERSITY CHICAGO 176 010727 DEVRY UNIVERSITY ALL IL LOCATIONS 055 001750 DOMINICAN UNIVERSITY RIVER FOREST 150 015310 EAST-WEST UNIVERSITY CHICAGO 014 001674 EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY CHARLESTON 015 001675 ELGIN COMMUNITY COLLEGE ELGIN 016 001676 ELMHURST UNIVERSITY ELMHURST 017 001678 EUREKA COLLEGE EUREKA 180 016924 FOX COLLEGE OAK LAWN 129 009145 GOVERNORS STATE UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY PARK 308 008938 GRAHAM HOSPITAL SCHOOL OF NURSING CANTON 019 001684 GREENVILLE UNIVERSITY GREENVILLE 114 001652 HAROLD -

Maccormac College 2017-2018 Academic Catalog

MacCormac College 2017-2018 Academic Catalog 29 E. Madison Street Chicago, Illinois 60602 312-922-1884 www.maccormac.edu Letter from the Chancellor As the Chancellor of MacCormac College, I have witnessed numerous progressive changes to the training of students, our culture, academic offerings, and campus facilities. The College continues to be on-path to become one of the nation’s premiere private, two-year, not-for profit colleges. I am very proud of the accomplishments and milestones that MacCormac has achieved throughout the past 113 years, upholding its mission to provide a transformative educational experience; challenging students to excel; preparing students to become lifelong learners; and encouraging students to be responsible citizens in our global community. MacCormac nurtures its diverse student body and maintains the best educational atmosphere to encourage personal and professional growth. Students at MacCormac receive hands-on, personal attention from qualified instructors with real-world industry experience. The small class sizes prove extremely beneficial for all ages and learning experiences and provide opportunities for cross-program discovery and involvement beyond the classroom. Our knowledgeable and service- oriented administrators maintain an open-door policy and regard all students as part of the MacCormac family. As students progress through their academic careers at MacCormac, they will find abounding opportunities designed to grow their knowledge base, strengthen their personal attributes, and develop as solid professionals prepared for the workforce or for their next level of education. This e-catalog is intended as a guide to MacCormac College’s program offerings as well as the College’s policies and other pertinent information for all of our students. -

Finding Part-Time Teaching Opportunities

Finding Part-Time Teaching Opportunities A Guide for Graduate Students and Postdocs OVERVIEW This resource provides UChicago graduate students and postdocs with guidance on finding part-time teaching opportunities, particularly in the Chicago area. UChicago graduate students, postdocs, and alumni are welcome to schedule one-on-one consultations with staff from UChicagoGRAD and the Chicago Center for Teaching to receive feedback on their job search strategies and job- related documents, including CVs and teaching statements. To schedule, log into GRAD Gargoyle (gradgargoyle.uchicago.edu) with your CNetID and select “Advising Appointments.” This guide focuses on three strategies for obtaining part-time teaching: (1) checking official job postings, (2) emailing potential employers, and (3) networking. 1. CHECK OFFICIAL JOB POSTINGS A. Search the websites of places where you would be interested in teaching. Many universities have pages displaying current openings or sites dedicated to handling job postings and applications. A list of colleges and universities in the Chicago area is provided on pages 7-8. B. Search larger portals where many colleges and universities publish job listings. HERC (Higher Ed Recruitment Consortium): https://www.hercjobs.org Higher Ed Jobs: https://www.higheredjobs.com/ Chronicle Vitae: https://chroniclevitae.com/job_search/new H-Net (Humanities and Social Sciences): https://www.h-net.org/jobs/home.php Diverse Issues in Higher Education, Diverse Jobs: http://diversejobs.net/ Professional Association Websites: Put those membership dues to good use and take advantage of the job postings and career services provided by many professional associations (e.g. AAA, AAR, SAA, AHA). 1 2. EMAIL POTENTIAL EMPLOYERS If you have a particular set of schools where you would like to work, but you haven’t located any specific job listings there, you can send a “cold-call” email introducing yourself, your academic background, and classes you could teach in the event that a position opens up. -

S T U D E Alverno College American Academy of Art Anderson University

S d t e u Southern Illinois University- Carbondale Alverno College Kishwaukee College St. Ambrose University American Academy of Art Lakeland College - Sheboygan St. Louis College of Pharmacy Anderson University Lawrence University The Illinois Institute Of Art Aurora University Lewis University Schaumburg Ball State University Maccormac College The University of Alabama Benedictine University MacMurray College The University of Tennessee- Cardinal Stritch University McKendree University Knoxville Carthage College Michigan State University The University of Toledo Central College Milwaukee School of Engineering Trinity International University Central Michigan University Missouri University of Science and Truman State University Chamberlain College of Nursing Technology United States Air Force Academy Chicago State University Morton College University of Illinois at Chicago Coe College Mount Mary University University of Illinois at Springfield Concordia University Chicago North Central College University of Illinois at Urbana- Concordia University-Wisconsin North Park University Champaign Defiance College Northeastern Illinois University University of Kentucky Dominican University Northern Illinois University University of Maryland, College Drake University Northwest Suburban College Park Drew University Northwest Suburban College University of Missouri-Columbia Eastern Illinois University Olivet Nazarene University University of Montana Elmhurst College Purdue University-Calumet Campus University of South Alabama FIDM-Fashion Institute -

Illinois College Information

Illinois College Information Public Four Year Colleges & Universities Chicago State University http://www.csu.edu/ Online Application Eastern Illinois University http://www.eiu.edu/ Online Application Governors State University http://www.govst.edu/ Online Application Illinois State University http://www.ilstu.edu/ Online Application Northeastern Illinois Online Application http://www.neiu.edu/ University Northern Illinois University http://www.niu.edu/ Online Application Southern Illinois University- Online Application www.siu.edu/siuc Carbondale Southern Illinois University- Online Application http://www.siue.edu/ Edwardsville University of Illinois-Chicago http://www.uic.edu/ Online Application University of Illinois- Online Application http://www.uis.edu/ Springfield University of Illinois- Online Application http://www.uiuc.edu/ Urbana/Champaign Western Illinois University http://www.wiu.edu/ Online Application Public Community Colleges Belleville Area Community College http://www.bacnet.edu/ Black Hawk College http://www.bhc.edu/ Black Hawk College-East Campus http://www.bhc.edu/ Carl Sandburg College http://www.csc.cc.il.us/ City Colleges-Chicago Harold Washington College http://www.ccc.edu/ Kennedy King College http://www.ccc.edu/ Malcolm X College http://www.ccc.edu/ Olive-Harvey College http://www.ccc.edu/ Richard J Daley College http://www.ccc.edu/ Truman College http://www.ccc.edu/ Wright College http://www.ccc.edu/ College of Du Page http://www.cod.edu/ College of Lake County http://www.clc.cc.il.us/ Danville Area Community -

List of Secondary Schools (As of 11/21/08)

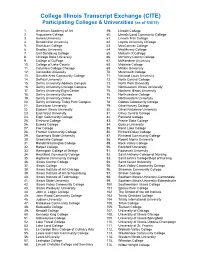

College Illinois Transcript Exchange (CITE) Participating Colleges & Universities (as of 5/8/15) 1. American Academy of Art 59. Lincoln College 2. Augustana College 60. Lincoln Land Community College 3. Aurora University 61. Lincoln Trail College 4. Benedictine University 62. Loyola University Chicago 5. Blackburn College 63. MacCormac College 6. Bradley University 64. MacMurray College 7. Carl Sandburg College 65. Malcolm X College 8. Chicago State University 66. McHenry County College 9. College of DuPage 67. McKendree University 10. College of Lake County 68. Midstate College 11. Columbia College Chicago 69. Millikin University 12. Concordia University 70. Monmouth College 13. Danville Area Community College 71. National Louis University 14. DePaul University 72. North Central College 15. DeVry University-Addison Campus 73. North Park University 16. DeVry University-Chicago Campus 74. Northeastern Illinois University 17. DeVry University-Elgin Center 75. Northern Illinois University 18. DeVry University-Gurnee 76. Northwestern College 19. DeVry University-Online 77. Northwestern University 20. DeVry University-Tinley Park Campus 78. Oakton Community College 21. Dominican University 79. Olive Harvey College 22. Eastern Illinois University 80. Olivet Nazarene University 23. East-West University 81. Olney Central College 24. Elgin Community College 82. Parkland College 25. Elmhurst College 83. Prairie State College 26. Eureka College 84. Quincy University 27. Fox College 85. Rend Lake College 28. Frontier Community College 86. Richard Daley College 29. Governors State University 87. Richland Community College 30. Greenville College 88. Robert Morris University 31. Harold Washington College 89. Rock Valley College 32. Harper College 90. Rockford University 33. Harrington College of Design 91. Roosevelt University 34. -

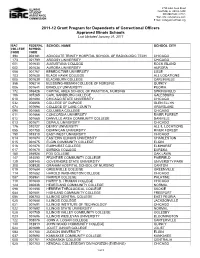

2011-12 Grant Program for Dependents of Correctional Officers Approved Illinois Schools Last Updated January 31, 2011

1755 Lake Cook Road ILLINOIS Deerfield, IL 60015-5209 STUDENT 800.899.ISAC (4722) ASSISTANCE Web site: collegezone.com COMMISSION E-mail: [email protected] 2011-12 Grant Program for Dependents of Correctional Officers Approved Illinois Schools Last Updated January 31, 2011 ISAC FEDERAL SCHOOL NAME SCHOOL CITY COLLEGE SCHOOL CODE CODE 394 004181 ADVOCATE TRINITY HOSPITAL SCHOOL OF RADIOLOGIC TECH CHICAGO 173 021799 ARGOSY UNIVERSITY CHICAGO 001 001633 AUGUSTANA COLLEGE ROCK ISLAND 002 001634 AURORA UNIVERSITY AURORA 058 001767 BENEDICTINE UNIVERSITY LISLE 103 001638 BLACK HAWK COLLEGE ALL LOCATIONS 005 001639 BLACKBURN COLLEGE CARLINVILLE 358 006214 BLESSING-RIEMAN COLLEGE OF NURSING QUINCY 006 001641 BRADLEY UNIVERSITY PEORIA 172 016426 CAPITAL AREA SCHOOL OF PRACTICAL NURSING SPRINGFIELD 106 007265 CARL SANDBURG COLLEGE GALESBURG 010 001694 CHICAGO STATE UNIVERSITY CHICAGO 032 006656 COLLEGE OF DUPAGE GLEN ELLYN 074 007694 COLLEGE OF LAKE COUNTY GRAYSLAKE 090 001665 COLUMBIA COLLEGE CHICAGO 011 001666 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY RIVER FOREST 012 001669 DANVILLE AREA COMMUNITY COLLEGE DANVILLE 013 001671 DEPAUL UNIVERSITY CHICAGO 176 010727 DEVRY UNIVERSITY ALL IL LOCATIONS 055 001750 DOMINICAN UNIVERSITY RIVER FOREST 150 015310 EAST-WEST UNIVERSITY CHICAGO 014 001674 EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY CHARLESTON 015 001675 ELGIN COMMUNITY COLLEGE ELGIN 016 001676 ELMHURST COLLEGE ELMHURST 017 001678 EUREKA COLLEGE EUREKA 180 016924 FOX COLLEGE OAK LAWN 147 014090 FRONTIER COMMUNITY COLLEGE FAIRFIELD 129 009145 GOVERNORS STATE UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY -

Information Pertinent to COVID-19 Responses/Actions for the Following Illinois Colleges and Universities Is Linked Below. Illin

Information pertinent to COVID-19 responses/actions for the following Illinois colleges and universities is linked below. Illinois Public Universities Illinois Community Colleges Chicago State University Black Hawk College Eastern Illinois University Carl Sandburg College Governors State University City Colleges of Chicago Illinois State University College of DuPage Northeastern Illinois University College of Lake County Northern Illinois University Danville Area Community College Southern Illinois University Carbondale Elgin Community College Southern Illinois University Edwardsville Harper College University of Illinois at Chicago Heartland Community College University of Illinois at Springfield Highland Community College University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Illinois Central College University of Illinois System Illinois Eastern Community Colleges Western Illinois University Illinois Valley Community College John A. Logan College John Wood Community College Joliet Junior College Kankakee Community College Kaskaskia College Kishwaukee College Lake Land College Lewis & Clark Community College Lincoln Land Community College McHenry County College Morton College Oakton Community College Parkland College Prairie State College Rend Lake College Richland Community College Rock Valley College Sauk Valley Community College Shawnee Community College South Suburban College Southeastern Illinois College Southwestern Illinois College Spoon River College Triton College Waubonsee Community College Moraine Valley Community College Created on