1-35 4Adachi 1.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stephen F. Austin State University English 463, Elements of Craft

Stephen F. Austin State University English 463, Elements of Craft Professor: Andrew Brininstool Section Number: 090 Office: LAN-256 Classroom: Ferguson 177 Office Hours: Tue: 11-12:30; Wed: 9-2 Meeting: TR 12:30-1:45 Email: [email protected] Phone: 936 468- 5659 “Randomness I love. And I still love just a holler right in the middle of an ongoing narrative. Pain or joy, ecstasy.” - Barry Hannah Overview The purpose of Elements of Craft is to help fiction writers improve their writing by training them to actively engage with texts--to read as a writer, rather than as a reader. In this course, we will be reading and discussing six larger texts (mostly novels) and two packets of shorter texts (mostly short stories), and while we will be discussing all of the elements that make up a piece of narrative art--setting, dialogue, characterization--the main thrust of this particular Elements course is concerned with the examination of perhaps the two most important literary styles of the twentieth and twenty-first century. In one corner, we have Minimalism. Antonin Chekhov (1860-1904) is often considered the father of what we now consider minimalist prose style. Rather than use this space to launch into a theoretical thesis on what Minimalism is and is not (don't worry: we'll be doing plenty of that later), here are a few brief quotes from writers who wrote or have written in this vein: Joan Didion: "I had...a technical intention...to write a novel so elliptical and fast that it would be over before you noticed it, a novel so fast that it would scarcely exist on the page at all....white space. -

Elizabeth Bishop. Selected Poems T.S. Eliot. the Waste Land, Four

20TH-/21ST-CENTURY AMERICAN LITERATURE GRADUATE COMPREHENSIVE EXAMINATION READING LIST SELECTED BY THE GRADUATE FACULTY THE CANDIDATE IS RESPONSIBLE FOR ALL WRITERS AND WORKS FROM LIST A, AT LEAST THREE WRITERS FROM LIST B, AND AT LEAST THREE WRITERS FROM LIST C. LIST A POETRY: Elizabeth Bishop. Selected Poems T.S. Eliot. The Waste Land, Four Quartets Robert Frost. North of Boston, Mountain Interval. Langston Hughes. One of the Following Collections: The Weary Blues, Fine Clothes to the Jew, Shakespeare in Harlem. (Poems in these collections may be pieced together from works in Hughes’ Collected Poems.) Sylvia Plath. Selected Poems Wallace Stevens. “Sunday Morning” and Other Selected Poems PROSE: Ralph Ellison. Invisible Man William Faulkner. As I Lay Dying; Light in August or The Sound and the Fury; “Barn Burning”; “Dry September”; “The Bear” (version in Go Down, Moses) F. Scott Fitzgerald. The Great Gatsby Ernest Hemingway. A Farewell to Arms, In Our Time Zora Neale Hurston. Their Eyes Were Watching God Maxine Hong Kingston. The Woman Warrior Toni Morrison. Beloved and One of the Following: Sula or The Bluest Eye 20th-/21st-Century American Literature 1 Rev. 1 August 2014 Flannery O’Connor. A Good Man Is Hard to Find and Other Stories or Everything That Rises Must Converge. John Steinbeck. The Grapes of Wrath or Of Mice and Men Eudora Welty. A Curtain of Green DRAMA: Susan Glaspell. Trifles Arthur Miller. Death of a Salesman Eugene O’Neill. One of the Following: Long Day’s Journey into Night, The Ice Man Cometh, or Moon for the Misbegotten Tennessee Williams. -

Thomas Pynchon: a Brief Chronology

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications, UNL Libraries Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln 6-23-2005 Thomas Pynchon: A Brief Chronology Paul Royster University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libraryscience Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Royster, Paul, "Thomas Pynchon: A Brief Chronology" (2005). Faculty Publications, UNL Libraries. 2. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libraryscience/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, UNL Libraries by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Thomas Pynchon A Brief Chronology 1937 Born Thomas Ruggles Pynchon Jr., May 8, in Glen Cove (Long Is- land), New York. c.1941 Family moves to nearby Oyster Bay, NY. Father, Thomas R. Pyn- chon Sr., is an industrial surveyor, town supervisor, and local Re- publican Party official. Household will include mother, Cathe- rine Frances (Bennett), younger sister Judith (b. 1942), and brother John. Attends local public schools and is frequent contributor and columnist for high school newspaper. 1953 Graduates from Oyster Bay High School (salutatorian). Attends Cornell University on scholarship; studies physics and engineering. Meets fellow student Richard Fariña. 1955 Leaves Cornell to enlist in U.S. Navy, and is stationed for a time in Norfolk, Virginia. Is thought to have served in the Sixth Fleet in the Mediterranean. 1957 Returns to Cornell, majors in English. Attends classes of Vladimir Nabokov and M. -

At the Tolstoy Museum’

UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ REPRESENTATIONS OF LEO TOLSTOY IN DONALD BARTHELME’S ‘AT THE TOLSTOY MUSEUM’ A proseminar paper by Kai Kajander DEPARTMENT OF LANGUAGES 2009 HUMANISTINEN TIEDEKUNTA KIELTEN LAITOS Kai Kajander REPRESENTATIONS OF LEO TOLSTOY IN DONALD BARTHELME’S ‘AT THE TOLSTOY MUSEUM’ Kandidaatintutkielma Englannin kieli Marraskuu 2009 25 sivua + 1 liite Käsillä oleva tutkielma on tulos mielenkiinnosta postmodernistiseksi kutsuttua kirjallisuu- den suuntausta kohtaan. Viimeisen viidenkymmenen vuoden ajan esillä ollutta kokeellista kirjallisuutta on yleisessä diskurssissa määritelty ennen kaikkea sotaisin metaforin. Post- modernistinen fiktio toisin sanoen tuhoaa, purkaa, rikkoo ja haastaa. Tämän kaltaiset ku- vaukset tyypittävät postmodernin kirjallisuuden ennen kaikkea reaktiiviseksi toiminnaksi. Kuitenkin postmoderni fiktio on ilmiönä moniselitteisempi ja laaja-alaisempi kuin yksin- kertaistavat luonnehdinnat antavat ymmärtää. Kandidaatintutkielmassani lähestyin ko. il- miötä tutkimalla yksittäistä, postmoderniksi luonnehdittavaa tekstiä. Amerikkalaiskirjailija Donald Barthelme on yksi postmodernistisen kirjallisuuden pionee- reista. Tämä tutkielma on analyysi hänen vuonna 1970 julkaisemastaan novellista ’At the Tolstoy Museum’. Tekstissä Barthelme parodioi venäläisen klassikkokirjailija Leo Tolstoin kirjallista ja kulttuurista perintöä. Tarkastelemalla Tolstoin representaatioita Barthelmen tekstissä tutkielma kartoitti Barthelmen suhdetta aikaisemman kirjallisuuden perintee- seen. Taustana tutkielmalle toimi joukko aikaisempia -

Dear Friends of the Kelly Writers House, Summertime at KWH Is Typically Dreamy

Dear Friends of the Kelly Writers House, Summertime at KWH is typically dreamy. We renovation of Writers House in 1997, has On pages 12–13 you’ll read about the mull over the coming year and lovingly plan guided the KWH House Committee in an sixteenth year of the Kelly Writers House programs to fill our calendar. Interns settle into organic planning process to develop the Fellows Program, with a focus on the work research and writing projects that sprawl across Kelly Family Annex. Through Harris, we of the Fellows Seminar, a unique course that the summer months. We clean up mailing lists, connected with architects Michael Schade and enables young writers and writer-critics to tidy the Kane-Wallace Kitchen, and restock all Olivia Tarricone, who designed the Annex have sustained contact with authors of great supplies with an eye toward fall. The pace is to integrate seamlessly into the old Tudor- accomplishment. On pages 14–15, you’ll learn leisurely, the projects long and slow. style cottage (no small feat!). A crackerjack about our unparalleled RealArts@Penn project, Summer 2014 is radically different. On May tech team including Zach Carduner (C’13), which connects undergraduates to the business 20, 2014, just after Penn’s graduation (when we Chris Martin, and Steve McLaughlin (C’08) of art and culture beyond the university. Pages celebrated a record number of students at our helped envision the Wexler Studio as a 16–17 detail our outreach efforts, the work we Senior Capstone event), we broke ground on student-friendly digital recording playground, do to find talented young writers and bring the Kelly Family Annex, a two-story addition chock-full of equipment ready for innovative them to Penn. -

The University of Oklahoma Graduate College

THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE THE SHORT WORKS OF DONALD BARTHELME A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY BARBARA LOUISE ROE Norman, Oklahoma 1982 THE SHORT WORKS OF DONALD BARTHELME APPROVED BY - ^ P L x/x/f — W Qa ^ — DISSERTATION COMMITTEE ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My gratitude extends to my friends, colleagues, and family members for supporting my efforts in writing this study. Those who considerately read this work during its tentative progress and helped to shape my ideas to their present form deserve a special thanks. I am particularly indebted to Professor Robert Murray Davis for encouraging my interest in Barthelme's literature, for patiently guiding me through the starts and stops of this project, and, above all, for his scrupulous editing of each chapter. I am also grateful to Farrar, Straus and Giroux for per mission to reproduce parts of Barthelme's collections. For my husband and children, the completion of this work is at once a source of joy, relief, and perhaps wonder. With unflagging devotion, they have cheered and sustained me, even though the task, I am sure, seemed endless. My deepest grati tude, therefore, is to T., T., and T .— a dynamite family. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS................. v Chapter I. INTRODUCTION ................... I II. THE PARODIES: FICTIONAL FORMS IN TRANSITION..................... 12 III. THE INVENTIVE FICTIONS: STRUCTURAL ALTERNATIVES FOR NARRATIVE AR T .................. 57 IV. THE INTERMEDIA COMPOSITIONS: EXTENDING THE PERIMETERS OF PLAY ............................. 112 V. AFTERWORD.........................190 BIBLIOGRAPHY ......................... 195 IV LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Page ILLUSTRATION 1 From Geoffrey Whitney: A Choice of Emblems ............... -

DONALD BARTHELME and WRITING AS POLITICAL ACT By

BEYOND FRAGMENTATION: DONALD BARTHELME AND WRITING AS POLITICAL ACT by DANIEL CHASKES B.A., Binghamton University, SUNY, 2001 M.A., University College London, 2005 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR A DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (English) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) May, 2012 © Daniel Chaskes, 2012 ABSTRACT “Beyond Fragmentation: Donald Barthelme and Writing as Political Act” extracts Barthelme from recursive debates over postmodernism and considers him, instead, within the intellectual contexts he himself recognized: the avant-garde, the phenomenological, and the transnational. It is these interests which were summoned by Barthelme in order to develop an aesthetic method characterized by collage, pastiche, and irony, and which together yielded a spirited response to political phenomena of the late twentieth century. I argue that Barthelme was an author who believed language had been corrupted by official discourse and who believed, more importantly, that it could be recovered through acts of combination and re-use. Criticism influenced by the cultural theory of Fredric Jameson has frequently labeled Barthelme’s work a mimesis of an age in which meaning had become devalued by rampant production and consumption. I revise this assumption by arguing that Barthelme’s work reacts to what was in fact a stubbornly efficient use of discourse for purposes of propaganda, bureaucracy, and public relations. Drawing on the biographical material available, and integrating that material with original archival work, I uncover the specific sources of Barthelme’s political discontent: Watergate, the war in Vietnam, a growing militarization in the United States, and the ideological rigidity of the 1960s counterculture. -

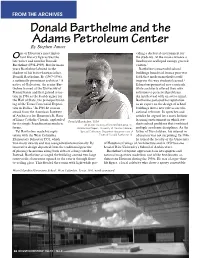

Donald Barthelme and the Adams Petroleum Center

FROM THE ARCHIVES Donald Barthelme and the Adams Petroleum Center By Stephen James ne of Houston’s most impor- viding a sheltered environment for Otant literary figures was the the students. At the main entrance a late writer and novelist Donald flamboyant scalloped canopy greeted Barthelme (1931–1989). But for many visitors.3 years Barthelme labored in the Barthelme’s successful school shadow of his better-known father, buildings benefitted from a post-war Donald Barthelme, Sr. (1907–1996), faith that modern methods could a nationally prominent architect.1 A improve the way students learned.4 native of Galveston, the senior Bar- Educators promoted new curricula thelme trained at the University of while architects offered their own Pennsylvania and first gained atten- solutions to perceived problems. tion in 1936 as the lead designer for An intellectual with an active mind, the Hall of State, the principal build- Barthelme parlayed his reputation ing of the Texas Centennial Exposi- as an expert on the design of school tion in Dallas.2 In 1948 he won an buildings into a new role as an edu- award from the American Institute cational reformer. In speeches and of Architects for Houston’s St. Rose articles he argued for a more holistic of Lima Catholic Church, applauded learning environment in which stu- Donald Barthelme, 1954. for its simple Scandinavian modern All photos courtesy of Donald Barthelme, Sr., dents solved problems that combined forms. Architectural Papers, University of Houston Libraries, multiple academic disciplines. As the Yet Barthelme made his repu- Special Collections Department by permission of father of five children, his interest in tation with the West Columbia Estate of Donald Barthelme, Sr. -

Ladies' Voices in Donald Barthelme's the Dead Father and Gertrude Stein's Dialogues

that Ugolin perhaps has had "too beautiful a dream. That suffices to deprive you of consolation at the definitive moment of decapitation" (p. 231). There is no answer to that conjecture, only the nothingness that typifies Ribemont-Dessaignes's phil osophical fiction.2 For one critic, Ribemont-Dessaignes's main theme is "the use- lessness of everything." Degradation and a concentration-camp universe encircle us. Jacques Lepage asks whether all acts are "a farce that one plays out in order to escape from the vacuity of existence." He finds this question in all R-D's novels. "Even in Céleste Ugolin, in which after the Dada'fsts' break with Breton he caricatures and vilifies the surrealists, the same question imposes itself."3 For another critic: "Céleste Ugolin, which appears in 1926, can be considered Ribemont-Dessaignes's first great novel, the one in which he abandons himself completely to surrealist inspiration, in which he puts on stage ... some of his surrealist friends. Of an exceptional virulence, this novel resembles no other, obeys no law of genre, has nothing which permits linking it to the surrealist works of the pe riod. Strange and profuse, an unsuspected vitality traverses the narrative from one end to the other, but it is by the cruelty of the episodes, by the brutal coloration of his style, sometimes also by the burlesque quality and black humor of certain pages, that Céleste Ugolin will remain a kind of archetype."4 Ladies' Voices in Donald Barthelme's The Dead Father and Gertrude Stein's Dialogues K.J. PHILLIPS, University of Hawaii Barthelme's The Dead Father (1975) contains four dialogues between Julie and Emma which are completely different from the rest of the book.1 These dialogues strikingly recall some of Stein's compositions, particularly "Every Afternoon: A Dialogue" and "Ladies' Voices (Curtain Raiser)," printed in her Geography and Plays (1922). -

The Subversion of Gender Stereotypes in Donald Barthelme's Snow White International Journal of Applied Linguistics & Engli

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature E-ISSN: 2200-3452 & P-ISSN: 2200-3592 www.ijalel.aiac.org.au The Subversion of Gender Stereotypes in Donald Barthelme’s Snow White Mashael H. Aljadaani*, Laila M. Al-Sharqi Department of European Languages & Literature, College of Arts and Humanities, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia Corresponding Author: Mashael H. Aljadaani, E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history Donald Barthelme’s Snow White redefines gender roles in the 20th century. Barthelme retells the Received: December 01, 2018 original fairy tale, subverting its presentation of stereotypical gender roles to depict postmodern Accepted: February 16, 2019 ideologies, particularly feminism. The male voice and its controlling power, embodied within Published: March 31, 2019 the original narrative, becomes the lost, weak, and subordinate side of his story. The female Volume: 8 Issue: 2 voice, repressed by social and cultural principles, is reshaped to represent the free, powerful, and Advance access: February 2019 dominant figure in his narrative. This novel’s presentation of Snow White’s characters reflects feminist battles, such as the fight for gender equality and women’s freedom from patriarchal restrictions or sexual objectification. Adopting a feminist perspective, this study investigates Conflicts of interest: None Barthelme’s demythologizing approach in Snow White to present his new identification of gender Funding: None roles. Specifically, this study examines the novel as a subversive reworking of Grimm’s Snow White [the original fairy tale] by analyzing Barthelme’s reframing of Snow White, the seven dwarfs, and Prince Paul. The findings of the study will show how Barthelme’s text offers a feminist critique of patriarchal dominance to the original Grimm’s fairy tale Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. -

IRONY 1S LIKING TUINGS: DONALD BARTHELME's POSTMODERN POETICS

IRONY 1s LIKING TUINGS: DONALD BARTHELME'S POSTMODERN POETICS BY MARK CAUGHL IN A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Depar tment ot Engl i sh University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba (c) August, 1997 National Library Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Semices services bibliographiques The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National LI* of Canada to Bibiiotheqe naîionale du Canada de reproduce, loan, disbn'bute or seJl reproduire, prêter, distncbuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/" de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantid extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. FACUL.TY OF GRADUATE STZTDIES **+a+ COPYRIGHT PERMISSION PAGE A Theris/Fracticum submitted to the Facaity olGmduate Studiu of The University of Manitoba in partial fmmentof the rqtürements of the dm of MSTKEOFAUS 1997 (c) Permission has been gnnted to the Libmry of The Univtnity oZM&nitobato lend or sel1 copies of this thesis/practicum, to the National Libm y of Canada to microWm this thesis and to lend or sell copies of the film, and to Dissemtions Abstncts International to publish am abtract of this thesidpmcticum. -

The Minimalist / Maximalist Interface in Frank Zappa and Captain Beefheart

Disciplined Excess: The Minimalist / Maximalist Interface in Frank Zappa and Captain Beefheart Michel Delville and Andrew Norris There are the minimalist pleasures of Emily Dickinson—“Zero at the Bone”—and the maximalist ones of Walt Whitman. John Barth Thereʹs no single ideal listener out there who likes my orchestral mu- sic, my guitar albums and songs like “Dyna-Moe-Humm.” Itʹs all one big note. Ladies and gentlemen . Frank Zappa Like Mozart’s “Marriage of Figaro,” Zappa’s music has often been accused of being far too noisy and of containing too many notes. Because of their density and com- plexity, his sound sculptures have alternately enthused and alienated several genera- tions of critics and listeners. With more than sixty albums (including no less than twenty-one double albums and two triple albums) released over a period of twenty- eight years, and fifteen “official bootlegs,” Zappa stands out as one of the most pro- lific artists of the 20th century, a composer whose sheer musical output could stand accused of maximalist excess. His attempts to embrace different genres and creative practices (rock, jazz, blues, orchestral music, film, opera,…) have often been inter- preted as a bulimic desire to explore the totality of past and present modes and styles in order to create strongly contrasting musical collages and establish his reputation as an outsider in both the rock and the art music communities. Certainly one of the difficulties in dealing with Frank Zappa’s (or anybody el- ses’s) maximalist art arises from the lack of serious attention to the development of maximalist aesthetics itself.