Management 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

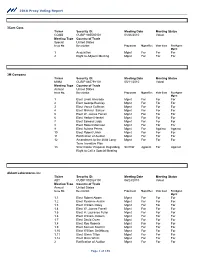

OUTPUT-WSIB Voting Report

2006 Proxy Voting Report 3M Company Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status MMM CUSIP9 88579Y101 05/09/2006 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No.Description Proponent Rec Vote Cast Mgmt 1.1Elect Linda Alvarado Mgmt For For For 1.2Elect Edward Liddy Mgmt For For For 1.3Elect Robert Morrison Mgmt For For For 1.4Elect Aulana Peters Mgmt For For For 2Ratification of Auditor Mgmt For For For Amendment to Certificate of Incorporation to Declassify the 3Board Mgmt For For For STOCKHOLDER PROPOSAL REGARDING EXECUTIVE 4COMPENSATION ShrHoldr Against Against For STOCKHOLDER PROPOSAL REGARDING 3M S ANIMAL 5WELFARE POLICY ShrHoldr Against Against For STOCKHOLDER PROPOSAL REGARDING 3M S BUSINESS 6OPERATIONS IN CHINA ShrHoldr Against Against For Abbott Laboratories Inc Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status ABT CUSIP9 002824100 04/28/2006 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No.Description Proponent Rec Vote Cast Mgmt 1.1Elect Roxanne Austin Mgmt For For For 1.2Elect William Daley Mgmt For For For 1.3Elect W. Farrell Mgmt For For For 1.4Elect H. Laurance Fuller Mgmt For For For 1.5Elect Richard Gonzalez Mgmt For For For 1.6Elect Jack Greenberg Mgmt For For For 1.7Elect David Owen Mgmt For For For 1.8Elect Boone Powell, Jr. Mgmt For For For 1.9Elect W. Ann Reynolds Mgmt For For For 1.10Elect Roy Roberts Mgmt For For For 1.11Elect William Smithburg Mgmt For For For 1.12Elect John Walter Mgmt For For For 1.13Elect Miles White Mgmt For For For RATIFICATION OF DELOITTE & 2TOUCHE LLP AS AUDITORS. Mgmt For For For SHAREHOLDER PROPOSAL - PAY-FOR-SUPERIOR- 3PERFORMANCE ShrHoldr Against Against For Page 1 of 139 2006 Proxy Voting Report SHAREHOLDER PROPOSAL - 4POLITICAL CONTRIBUTIONS ShrHoldr Against Against For SHAREHOLDER PROPOSAL - 5THE ROLES OF CHAIR AND CEO . -

Gibson Dunn 2

Practice Group Overviews: Anti Money Laundering Financial Institutions Securities Litigation Contents Anti-Money Laundering Practice ........................................................................................................................... 3 Financial Institutions Practice ................................................................................................................................ 6 Securities Litigation Practice .................................................................................................................................. 9 Selected Attorney Profiles .................................................................................................................................... 26 Gibson Dunn 2 Anti-Money Laundering Practice Lawyers at Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher are recognized as leaders in providing advice to financial institutions and other businesses on issues related to compliance with anti-money laundering and economic sanctions laws and regulations and the development of global and risk-based anti-money laundering compliance programs. The Anti-Money Laundering practice provides legal and regulatory advice to all types of financial institutions and nonfinancial businesses with respect to compliance with federal and state anti-money laundering laws and regulations, including the U.S. Bank Secrecy Act as amended by the USA PATRIOT Act. We represent clients in criminal and regulatory government investigations. We have developed extensive knowledge and broad anti-money laundering -

Mothers of Invention: Women in Technology

Mothers of Invention: Women in Technology n old adage counsels, “Maternity Rideout (AZT), M. Katherine Holloway and is a matter of fact… paternity is Chen Zhao (protease inhibitors), and Diane a matter of opinion.” And indeed, Pennica (tissue plasminogen activator).2 Awhen it comes to people, the evidence of By 1998, women accounted for 10.3 who physically bears the child is visible and percent of all U.S.–origin patents granted undeniable. With the gestation of ideas, annually. Innovation professionals believe this however, lineage is less clear. percentage will continue to increase. A recent The evidence for women’s role in survey of one thousand U.S. researchers technology has been obscured historically. yielded the names of twenty U.S. scientists Only two percent of the fi ve hundred Nobel under the age of forty who have demonstrated Prize Laureates recognized for scientifi c once-in-a-generation insight. Nine of them— achievement are women. As recently as the almost half—are women.3 Jennifer A. Kurtz early 1980s, U.S. Patent and Trademark Offi ce records show that only 2.8 percent of patents Research Fellow, Indiana went to women each year. This participation Business Research Center, rate did not differ much from the 1 percent or Women must Kelley School of Business, so of patents that went to women in the period increasingly pursue Indiana University from 1790 to 1895.1 Young women have had relatively few role science and models to encourage their pursuit of scientifi c and technological adventures. That pattern has technology to ensure begun to change as women are increasingly that the future needs present in all dimensions of the innovation life cycle: knowledge creation, technology transfer, for a skilled U.S. -

Access to Experts

Access to Experts Patricia Russo Pat Russo is the retired Chief Executive Officer of Alcatel-Lucent. She was a driving force and a key architect behind the creation of Alcatel-Lucent, making this merger the first bold move in an industry ripe for consolidation. Under her leadership, from December 2006 through September, 2008 Alcatel-Lucent strengthened its market positions in a number of areas, such as optical and wireless networking and services, enhanced customer relationships, improved its operating efficiency and streamlined its management structure. Prior to the merger of Alcatel and Lucent, Russo was Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of Lucent Technologies for five years. She led the company through one of the most challenging periods in the telecom industry’s history, returning the company to profitability after the severe telecom industry ‘crash’. Under her leadership Lucent embarked on a new strategy to enhance its services capabilities, implemented a new operating model, developed a more customer focused culture, expanded into emerging markets and enhanced the role and reach of Bell Labs. As one of the founding executives of Lucent, she helped launch the company in 1996 and over more than a 20 year career, managed some of Lucent’s and AT&T’s largest divisions and most critical corporate functions. Before joining AT&T, Russo spent eight years in sales and marketing at IBM. Just prior to returning to Lucent as its CEO in January of 2002, Russo served as president and chief operating officer of Kodak where she helped to reshape its strategy and operations to compete effectively in the transformation to digital technology. -

HP Today Presentation Notes to Speaker

HP Today Peter Moser, Director and Chief Technologist May, 2015 © Copyright 2014 Hewlett-Packard Development Company, L.P. The information contained herein is subject to change without notice. Safe harbor This presentation contains forward-looking statements that involve risks, uncertainties and assumptions, relating to, among other things, the planned separation. If the risks or uncertainties ever materialize or the assumptions prove incorrect, the results of HP may differ materially from those expressed or implied by such forward-looking statements and assumptions. All statements other than statements of historical fact are statements that could be deemed forward-looking statements, including but not limited to any statements of the plans, strategies and objectives of HP for future operations, including the separation transaction; the future performance of Hewlett-Packard Enterprise and HP Inc. if the separation is completed; the execution of restructuring plans and any resulting cost savings or revenue or profitability improvements; any projections of revenue, margins, expenses, HP’s effective tax rate, net earnings, net earnings per share, cash flows, benefit plan funding, share repurchases, currency exchange rates or other financial items; any projections of the amount, timing or impact of cost savings or restructuring charges; any statements concerning the expected development, performance, market share or competitive performance relating to products or services; any statements regarding current or future macroeconomic trends or events and the impact of those trends and events on HP and its financial performance; any statements regarding pending investigations, claims or disputes; any statements of expectation or belief; and any statements of assumptions underlying any of the foregoing. -

Your Questions, Our Answers Questions from Hewlett Packard Enterprise Company 2018 Annual Shareholder Meeting

Your Questions, Our Answers Questions from Hewlett Packard Enterprise Company 2018 Annual Shareholder Meeting Questions from Hewlett Packard Enterprise Company 2018 Annual Shareholder Meeting April 9, 2018 We pride ourselves on our robust shareholder outreach program. Our Annual Shareholder Meeting is one of the key elements of this outreach, intended to provide a corporate update and a forum for management and the Board to answer shareholder questions. We’ve created and implemented a completely virtual annual meeting in order to facilitate shareholder attendance and participation by enabling our shareholders to participate fully from any location around the world at no cost. In addition, the online format allows us to communicate with you in advance of and during the meeting so you can ask any question of our Board and management. Further, we have committed to answering each and every single question that we received. All questions are presented, as submitted, censored or edited only to remove identifiying, confidential, or offensive content, received both during and prior to the meeting, sorted by topic. We have removed any identifying information such as names or e-mail addresses submitted along with questions. All responses are as of April 4, 2018 unless otherwise noted. HPE assumes no obligation and does not intend to update its responses below. If you have any questions or concerns please feel free to contact investor relations by visiting http://investors.hpe.com/contact-us. We sincerely thank each of you for your questions and comments and for your ongoing support as a shareholder of Hewlett Packard Enterprise Company. Strategy Company Strategy “should your business model and marketing approach be changed” Response: HPE is in a strong position today made possible by the work we’ve done over the last several years to transform the company, improve customer satisfaction and productivity, reinvigorate our culture and most importantly, reignite innovation and deliver ground-breaking new technology solutions. -

Case 6 EASTMAN KODAK: MEETING the DIGITAL CHALLENGE*

Case 6 EASTMAN KODAK: MEETING THE DIGITAL CHALLENGE* On Monday April 16, 2001, Patricia F. Russo began her new appointment as President and Chief Operating Officer of Eastman Kodak Company, reporting to Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Dan Carp. The press release announcing her appointment stated: “Russo will oversee the day-to-day operations of Kodak's operating divisions and serve as the CEO's strategic partner in pursuing the business opportunities created by the convergence of imaging and information management technologies.”1 In addition to her role as President and COO, Russo also headed up the Consumer Group, Kodak’s biggest operating division (see Figure 6.1). Pat Russo’s appointment to the number two position in Kodak’s top management team marked the high point of an outstanding career in IT and telecommunications. After graduating from Georgetown University with a degree in political science and history, Russo spent eight years with IBM before joining AT&T in 1982. In the tumultuous years following the breakup of AT&T's Bell system, Russo held management positions ranging from human resources to strategic planning, and completed Harvard’s Advanced Management Program in 1989. In 1992, Ms Russo took charge of AT&T's business communications equipment division, which was then spun off as part of the new Lucent group. The Kodak press release noted that: Russo brings to Kodak more than twenty years of broad management experience in the computing and communications industries: As President of the Business Communications Systems division of AT&T Corp. and Lucent Technologies Inc. from 1993 through 1997, Russo drove the successful turnaround of a $6 billion technology business. -

2010 Proxy Voting Report 3Com Corp. Ticker Security ID

2010 Proxy Voting Report 3Com Corp. Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status COMS CUSIP 885535104 01/26/2010 Voted Meeting Type Country of Trade Special United States Issue No. Description Proponent Mgmt Rec Vote Cast For/Agnst Mgmt 1 Acquisition Mgmt For For For 2 Right to Adjourn Meeting Mgmt For For For 3M Company Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status MMM CUSIP 88579Y101 05/11/2010 Voted Meeting Type Country of Trade Annual United States Issue No. Description Proponent Mgmt Rec Vote Cast For/Agnst Mgmt 1 Elect Linda Alvarado Mgmt For For For 2 Elect George Buckley Mgmt For For For 3 Elect Vance Coffman Mgmt For For For 4 Elect Michael Eskew Mgmt For For For 5 Elect W. James Farrell Mgmt For For For 6 Elect Herbert Henkel Mgmt For For For 7 Elect Edward Liddy Mgmt For For For 8 Elect Robert Morrison Mgmt For For For 9 Elect Aulana Peters Mgmt For Against Against 10 Elect Robert Ulrich Mgmt For For For 11 Ratification of Auditor Mgmt For For For 12 Amendment to the 2008 Long- Mgmt For For For Term Incentive Plan 13 Shareholder Proposal Regarding ShrHldr Against For Against Right to Call a Special Meeting Abbott Laboratories Inc Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status ABT CUSIP 002824100 04/23/2010 Voted Meeting Type Country of Trade Annual United States Issue No. Description Proponent Mgmt Rec Vote Cast For/Agnst Mgmt 1.1 Elect Robert Alpern Mgmt For For For 1.2 Elect Roxanne Austin Mgmt For For For 1.3 Elect William Daley Mgmt For For For 1.4 Elect W. -

The Tech Edge Fave, Juniper, Has Some VPN Business Brewing

Issue 5: Tuesday, January 8, 2002 In This Issue Page 1 Tech Focus: Virtual Networks = Real Opportunity Page 3 Tech Screen: Low-Grade Debt Spells Trouble Page 4 Tech Sector Updates Page 6 George Mannes: Beware the Tech Sirens Page 6 Reader Feedback and Questions for Scott Moritz Tech Focus: Virtual Networks = Real Opportunity As phone companies attempt to shift from cash-burning to cash-earning strategies, virtual private networks (VPNs) offer one of the few new offerings that may please the bean counters. VPNs allow encrypted information to “tunnel” from point to point, through the Internet and the public phone network. As such, VPNs serve as a far cheaper alternative to the conventional method of hauling secure data along specially installed, dedicated lines. CIBC World Markets’ equipment analyst Steve Kamman says these private-line data services, which typically use frame-relay or asynchronous transfer mode (ATM) protocols to ship information, amount to a $26 billion-a-year business for the telcos. Introduced as cheap, secure computer links between employee homes and office networks, VPNs simultaneously became the telecommuters’ lifeline, and the tech support staffs’ nightmare. Since VPNs use existing networks, revenue-hungry telcos don’t face steep upfront construction costs before they can tap this lucrative market. And with a much lower-cost technology, Kamman says the telcos can offer alternative data services at cheaper prices with higher margins. Sensing this outsourcing opportunity, telcos increasingly are offering to take the burden off IT teams and manage the whole range of corporate VPN data services, from remote access to corporate private line alternatives. -

2020 PROXY STATEMENT Hehewllett Pap Ckkara D 20200 Proxy Statemeent Enteerprisee Hewlett Packard 2020 Proxy Statement Enterprise

2020 PROXY STATEMENT HeHewllett PaP ckkara d 20200 Proxy Statemeent Enteerprisee Hewlett Packard 2020 Proxy Statement Enterprise The year 2020 has ushered in a new decade, when every organization, everywhere, will undergo unprecedented digital transformation. In a world where billions of users and devices and trillions of things are connected, the apps and data that create and run our customers’ businesses live everywhere—in the cloud, on and off premises, and increasingly at the edge. As the edge-to-cloud platform as-a-service company, Hewlett Packard Enterprise is at the forefront of this evolution, making this an exciting chapter for our company, customers, team members, and shareholders. Our purpose is to advance the way people live and work. I am tremendously proud of this mission and of our proven ability to help customers harness the power of their data in compelling new ways. I am also excited and optimistic about what comes next, especially given our enhanced portfolio and our strategic shift to as-a-service, which we believe will drive sustainable, profitable growth. A strong finish to the decade I am enthusiastic for what lies ahead because I’ve seen us transform significantly already and I know our many stakeholders are counting on us. In 2019, customers reaffirmed their need for hybrid capabilities that will advance their transformations, and they turned to HPE because of our unique ability to offer an edge-to-cloud architecture and experience. Customers also told us they don’t want to spend their resources managing their infrastructure. They want to focus on their own innovation while lowering costs and maintaining control. -

Reese Witherspoon Incredibly Taxing Because of Our Schedules Crying in the Driveway

QUAD: pls. extend pic to bleed and clone to gutter APRs IN QUAD PLS PLACE Text Revise Art Director Color Revise SILICON SHOWDOWN Carly Fiorina after the shareholders’ meeting in Cupertino, California, at which she closed the voting on the Hewlett-Packard/ Compaq merger, March 19, 2002. Opposite, Walter Hewlett arriving for the same meeting. The Battle for H 0602VF WE-158 CYAN MAGENTA YELLOW BLACK NOTES: APRs IN QUAD PLS PLACE Text Revise Art Director Color Revise Hewlett-Packard’s chairman and C.E.O., Carly Fiorina, was sure a merger with Compaq would be her company’s salvation. Walter Hewlett, son of the famously folksy co-founder, was sure the merger would destroy it. Their bitter proxy fight may have wounded the $45.2 billion computer giant beyond measure. Reporting on the clash between the world’s top female chief executive— nicknamed “Rock Star” for her aloof, Armani-clad style—and the rumpled, low-key Hewlett, with his battalion of ultra-egalitarian H-P employees, VICKY WARD reveals the stakes: a woman’s reputation, a family’s legacy, and a company’s soul LEFT, BY NORBERT SCHWERIN; RIGHT, BY JUSTIN SULLIVAN or Hewlett-Packard 0602VF CYAN MAGENTA YELLOW BLACK WE-159 NOTES: APRs IN QUAD PLS PLACE Text Revise Art Director Color Revise that the merger would give H-P the scale it took the microphone. He spoke softly and needed to compete with IBM and Dell in clearly: “I love this company,” he recalls a market demanding increasingly complex telling Fiorina. “Twenty-two years ago I systems and services. -

Please Find Enclosed the Combined Proxy Statement/Prospectus

INFORMATIONAL MATERIALS FOR HEWLETT PACKARD ENTERPRISE STOCKHOLDERS Please find enclosed the combined proxy statement/prospectus-information statement containing important information about the previously announced spin-off of our enterprise services business, Everett SpinCo, Inc., and the subsequent merger of Everett SpinCo, Inc. with Computer Sciences Corporation. Hewlett Packard Enterprise Company (HPE) stockholders are not required to vote on the proposed transactions and are not being asked to vote on the proposed transactions. HPE is not asking HPE stockholders for a proxy, and HPE stockholders are requested not to send HPE a proxy. February 27, 2017 Dear Fellow Stockholders: As previously announced, Computer Sciences Corporation (“CSC”) has entered into an Agreement and Plan of Merger with Hewlett Packard Enterprise Company, a Delaware corporation (“HPE”), Everett SpinCo, Inc., a Delaware corporation and a wholly-owned subsidiary of HPE (“Everett”), and New Everett Merger Sub Inc., a Nevada corporation and a wholly-owned subsidiary of Everett (“Merger Sub”), which provides for a series of transactions described below pursuant to which HPE will transfer its Enterprise Services business to wholly- owned subsidiaries of Everett and distribute all the shares of Everett to HPE stockholders (the “Merger Agreement”). Following the distribution, Merger Sub will merge with and into CSC, and CSC will continue as a wholly-owned subsidiary of Everett. At the time of the Merger, Everett will change its name to DXC Technology Company. The principal