Miami Herald Miami, Florida 16 December 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

As Mulheres E O Poder Executivo Em Perspectiva Comparada – De Fhc a Dilma

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE VIÇOSA CENTRO DE CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS DEPARTAMENTO DE CIÊNCIAS SOCIAIS SAVANA BRITO FERREIRA POLÍTICA DA VISIBILIDADE: AS MULHERES E O PODER EXECUTIVO EM PERSPECTIVA COMPARADA – DE FHC A DILMA VIÇOSA-MG 2013 SAVANA BRITO FERREIRA POLÍTICA DA VISIBILIDADE: AS MULHERES E O PODER EXECUTIVO EM PERSPECTIVA COMPARADA – DE FHC A DILMA Monografia apresentada ao Departamento de Ciências Sociais da Universidade Federal de Viçosa como parte das exigências para obtenção do título de Bacharel em Ciências Sociais. Orientador: Professor Diogo Tourino Sousa VIÇOSA-MG 2013 SAVANA BRITO FERREIRA POLÍTICA DA VISIBILIDADE: AS MULHERES E O PODER EXECUTIVO EM PERSPECTIVA COMPARADA – DE FHC A DILMA Monografia apresentada ao Departamento de Ciências Sociais da Universidade Federal de Viçosa como parte das exigências para obtenção do título de Bacharel em Ciências Sociais. Orientador: Professor Diogo Tourino Sousa DATA DA DEFESA: 05 de setembro de 2013 RESULTADO:_______________________ Banca: ____________________________________________ Profª Ma. Tatiana Prado Vargas (DCS – UFV) ____________________________________________ Profº Me. Igor Suzano Machado (DCS – UFV) ____________________________________________ Profº Diogo Tourino Sousa (DCS – UFV) DEDICATÓRIA Às mulheres negras guerreiras, resistentes e lutadoras, Dandaras e Elzas. Aos seres encantad@s, fadas, doendes, gnomos, sapas, bees, travas... Às mulheres que jamais deixarão de me inspirar. AGRADECIMENTO À minha família, sobretudo mãe e irmão, por garantirem minha permanência na Universidade e respeitarem minhas decisões na trajetória de mudanças de curso. Às muitas e aos muitos amigos que marcaram minha trajetória acadêmica e pessoal. Às professoras e professores a quem desejo fazer saber da minha admiração: Diogo Tourino, a quem tive o prazer de ter como orientador, Daniela Rezende, Daniela Alves, Marcelo Oliveira, Douglas Mansur, Vera e Nádia. -

Shipbreaking Bulletin of Information and Analysis on Ship Demolition # 60, from April 1 to June 30, 2020

Shipbreaking Bulletin of information and analysis on ship demolition # 60, from April 1 to June 30, 2020 August 4, 2020 On the Don River (Russia), January 2019. © Nautic/Fleetphoto Maritime acts like a wizzard. Otherwise, how could a Renaissance, built in the ex Tchecoslovakia, committed to Tanzania, ambassador of the Italian and French culture, carrying carefully general cargo on the icy Russian waters, have ended up one year later, under the watch of an Ukrainian classification society, in a Turkish scrapyard to be recycled in saucepans or in containers ? Content Wanted 2 General cargo carrier 12 Car carrier 36 Another river barge on the sea bottom 4 Container ship 18 Dreger / stone carrier 39 The VLOCs' ex VLCCs Flop 5 Ro Ro 26 Offshore service vessel 40 The one that escaped scrapping 6 Heavy load carrier 27 Research vessel 42 Derelict ships (continued) 7 Oil tanker 28 The END: 44 2nd quarter 2020 overview 8 Gas carrier 30 Have your handkerchiefs ready! Ferry 10 Chemical tanker 31 Sources 55 Cruise ship 11 Bulker 32 Robin des Bois - 1 - Shipbreaking # 60 – August 2020 Despina Andrianna. © OD/MarineTraffic Received on June 29, 2020 from Hong Kong (...) Our firm, (...) provides senior secured loans to shipowners across the globe. We are writing to enquire about vessel details in your shipbreaking publication #58 available online: http://robindesbois.org/wp-content/uploads/shipbreaking58.pdf. In particular we had questions on two vessels: Despinna Adrianna (Page 41) · We understand it was renamed to ZARA and re-flagged to Comoros · According -

MEDIA RESOURCE NEWS Suffolk County Community College Libraries August 2014

MEDIA RESOURCE NEWS Suffolk County Community College Libraries August 2014 Ammerman Grant Eastern Rosalie Muccio Lynn McCloat Paul Turano 451-4189 851-6742 548-2542 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 8 Women/8 Femmes. A wealthy industrialist is found murdered in his home while his family gathers for the holiday season. The house is isolated and the phone lines have been found to be cut. Eight women are his potential murderers. Each is a suspect and each has a motive. Only one is guilty. In French with subtitles in English or Spanish and English captions for the hearing impaired. DVD 1051 (111 min.) Eastern A La Mar. "Jorge has only a few weeks before his five-year-old son Natan leaves to live with his mother in Rome. Intent on teaching Natan about their Mayan heritage, Jorge takes him to the pristine Chinchorro reef, and eases him into the rhythms of a fisherman's life. As the bond between father and son grows stronger, Natan learns to live in harmony with life above and below the surface of the sea."--Container. In Spanish, with optional English subtitles; closed-captioned in English. DVD 1059 (73 min.) Eastern Adored, The. "Maia is a struggling model. After suffering a major loss, her relationship with her husband is thrown into turmoil. She holds high hopes that a session with the prolific celebrity photographer, Francesca Allman, will rejuvenate her career and bring her out of her depression. However, Francesca suffers from severe OCD and has isolated herself in remote North West Wales in a house with an intriguing past. -

Celebrity's Spectacular

Vol. 17 NO 1 WINTER / SPRING 2019 www.cruiseandtravellifestyles.com MOLOKAI & MAUI ALOHA WELCOME ABOARD Symphony of the Seas CELEBRITY’S SPECTACULAR Canada $5.95 $5.95 Canada Edge Great Canadian SPA RETREATS VIKING SEA IN THE CARIBBEAN | AZAMARA JOURNEY IN NEW ZEALAND We give you Access to the world.™ GO ALL-IN on a Caribbean Cruise + RECEIVE FREE Drinks + FREE WiFi 1 On Caribbean sailings aboard MSC ARMONIA, MSC SEASIDE, MSC DIVINA & MSC MERAVIGLIA Must ask for “All-In Drinks & Wifi” promotion when booking. Offer is available for all Caribbean sailings from Miami on MSC Armonia Dec 10, 2018 to Mar 30, 2020; MSC Seaside Dec 1, 2018 to Mar 28, 2020; MSC Divina Dec 9, 2018 to Mar 3, 2019 & Nov 25, 2019 to Mar 13, 2020; and MSC Meraviglia Oct 8, 2019 to Apr 5, 2020. Also available on two cruises from New York on MSC Meraviglia Oct 8 & 18, 2019. 1. Free Drinks: unlimited drinks for Caribbean sailings that include select alcoholic and non-alcoholic drinks. Enjoy a selection of house wines by the glass, bottled and draft beers, selected spirits and cocktails, non-alcoholic cocktails, soft drinks and fruit juices by the glass, bottled mineral water, classic hot drinks and chocolate delights. Free Wi-Fi: offer includes “Standard Internet” package, which gives access to all social networks and chat APPs, check email and browse the web. Up to 2 devices. Data limit varies by duration: MSC Divina, 3-night cruises from Miami: data limit 1 GB. MSC Divina, MSC Meraviglia and MSC Armonia, 7-night cruises from Miami: data limit 2 GB. -

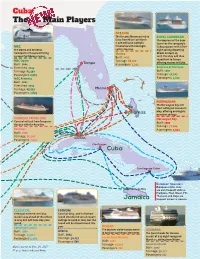

Cuba: the Main Players

Cuba: The Main Players OCEANIA The Oceania Marina sailed to ROYAL CARIBBEAN Cuba from Miami on March The Empress of the Seas 7, and will have multiple launches the company’s MSC itineraries with overnight Cuba program with a ve- The Opera and Armonia calls in Havana. night sailing departing homeport in Havana offering Marina Miami on April 19, various Caribbean cruises. Built: 2011 2017. The ship will then MSC Opera Tonnage: 66,000 reposition to Tampa offering cruises to Cuba. Built: 2004 Tampa Passengers: 1,252 Stretched: 2015 Empress of the Seas Tonnage: 65,591 Built: 1990 Passengers: 2,679 Tonnage: 48,563 MSC Armonia Passengers: 1,840 Built: 2001 Stretched: 2014 Tonnage: 65,591 Miami Passengers: 2,679 NORWEGIAN The Norwegian Sky will The start calling on Havana in May, offering overnights Bahamas on select sailings. CARNIVAL CRUISE LINE Norwegian Sky Carnival will sail from Tampa to Built: 1999 Havana with the Paradise. Tonnage: 77,104 Paradise Passengers: 2,oo4 Built: 1998 Tonnage: 70,367 HAVANA Passengers: 2,052 Cienfuegos Cuba Santiago de Cuba European Operators European cruise lines Montego Bay are also frequent visitors. Plantours, Fred. Olsen, FTI, Thomson and Saga are Jamaica frequent callers in Havana. CELESTYAL FATHOM Celestyal entered the Cuba Carnival Corp. and its Fathom market way ahead of the others brand introduced social-impact in 2013 and will now stay year- sailings to Cuba in 2016, but the round. brand will be discontinued this Celestyal Crystal year. REGENT The Mariner visits Havana twice Built: 1980 Adonia AZAMARA in April on Caribbean itineraries. The Quest heads for Havana Tonnage: 25,611 Built: 2001 Seven Seas Mariner as part of a 13-night voyage on Passengers: 1,400 Tonnage: 30,277 March 21, sailing from Miami. -

BREAKING BAD by Vince Gilligan

BREAKING BAD by Vince Gilligan 5/27/05 AMC Sony Pictures Television TEASER EXT. COW PASTURE - DAY Deep blue sky overhead. Fat, scuddy clouds. Below them, black and white cows graze the rolling hills. This could be one of those California "It's The Cheese" commercials. Except those commercials don't normally focus on cow shit. We do. TILT DOWN to a fat, round PATTY drying olive drab in the sun. Flies buzz. Peaceful and quiet. until ••• ZOOOM! WHEELS plow right through the shit with a SPLAT. NEW ANGLE - AN RV Is speeding smack-dab through the pasture, no road in sight. A bit out of place, to say the least. It's an old 70's era Winnebago with chalky white paint and Bondo spots. A bumper sticker for the Good Sam Club is stuck to the back. The Winnebago galumphs across the landscape, scattering cows. It catches a wheel and sprays a rooster tail of red dirt. INT. WINNEBAGO - DAY Inside, the DRIVER's knuckles cling white to the wheel. He's got the pedal flat. Scared, breathing fast. His eyes bug wide behind the faceplate of his gas mask. Oh, by the way, he's wearing a GAS MASK. That, and white jockey UNDERPANTS. Nothing else. Buckled in the seat beside him lolls a clothed PASSENGER, also wearing a gas mask. Blood streaks down from his ear, blotting his T-shirt. He's passed out cold. Behind them, the interior is a wreck. Beakers and buckets and flasks -- some kind of ad-hoc CHEMICAL LAB -- spill their noxious contents with every bump we hit. -

The Lynching of Cleo Wright

University of Kentucky UKnowledge United States History History 1998 The Lynching of Cleo Wright Dominic J. Capeci Jr. Missouri State University Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Capeci, Dominic J. Jr., "The Lynching of Cleo Wright" (1998). United States History. 95. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_united_states_history/95 The Lynching of Cleo Wright The Lynching of Cleo Wright DOMINIC J. CAPECI JR. THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 1998 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine College, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Club Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 02 01 00 99 98 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Capeci, Dominic J. The lynching of Cleo Wright / Dominic J. Capeci, Jr. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Governo Dilma

Antônio Augusto de Queiroz PERFIL , PRO P OSTAS E PERS P ECTIVAS DO GOVERNO DILMA 1ª Edição Brasília-DF 2011 Antônio Augusto de Queiroz PERFIL , PRO P OSTAS E PERS P ECTIVAS DO GOVERNO DILMA Perfil, Propostas e Perspectivas do Governo Dilma Ficha Técnica A série Estudos Políticos é uma publicação do Diap (Departamento Intersindical de Assessoria Parlamentar) Supervisão Ulisses Riedel de Resende Pesquisa e texto Antônio Augusto de Queiroz Coordenação editorial Viviane Ponte Sena Colaboradores da equipe do Diap André Luis dos Santos Alysson de Sá Alves Iva Cristina Pereira Sant´Ana Marcos Verlaine da Silva Pinto Neuriberg Dias do Rego Ricardo Dias de Carvalho Viviane Ponte Sena Editoração eletrônica e capa F4 Comunicação Impressão Gráfika Papel e Cores Queiroz, Antônio Augusto de. Perfil, Propostas e Perspectivas do Governo Dilma / pesquisa e texto: Antônio Augusto de Queiroz. -- Brasília : Diap, 2011. 120 p. (Série estudos políticos) ISBN 978-85-62483-05-9 1. Rousseff, Dilma, 1947- . 2. Política e governo, Brasil, 2011. 3. Programa de governo, Brasil, 2011-. I. Título. CDU 32(81) APRESENT A ÇÃO É com grande satisfação que o Departamento Intersindical de Assessoria Parlamentar – DIAP lança a publicação “Perfil, Propostas e Perspectivas do Governo Dilma”, da série Estudos Políticos, na qual analisa o processo eleitoral, os critérios de montagem da equipe, os desafios pessoais e estruturais da presidente, a agenda oficial, além dos principais operadores no Poder Executivo e no Congresso. Com esta publicação faz-se um diagnóstico sobre o padrão de atuação do governo nos três primeiros meses de mandato e um prognóstico sobre a administração de Dilma Rousseff, oferecendo à sociedade em geral e às lideranças sindicais em particular um mate- rial de referência sobre os interesses, desafios e prioridades do novo governo. -

Msc Sinfoniacruise Guide 2015/2016

MSC SINFONIACRUISE GUIDE 2015/2016 Powered by CREATING MEMORIES Year after year Premier Private Resorts has been delivering an unrivalled service to its members: creating memories to be cherished and looked back upon for years to come. When that last our members recall a fabulous holiday they have had, we are a lifetime... proud to have been part of that experience. We constantly endeavour to expand our portfolio, bringing new and exciting experiences into reality, catering to ever-growing desires and travel goals for all our members. In collaboration with MSC Cruises, we are pleased to offer a fantastic variety of cruises giving you the chance to escape from it all - whether it is a family getaway, romantic retreat or weekend of fun with friends, the MSC Sinfonia has just what you need. There is no better value-for-money than a cruise holiday. Whether you want to cruise for a short while or longer period, we have a cruise that is right for you. Premier Private Resorts also offers you the opportunity to journey to the world’s most exciting locations such as the Mediterranean, Caribbean, Alaska, Northern Europe, Bahamas, Panama Canal and more, on the world’s best-loved cruise ships. Sun yourself on the upper deck, take a dip in the pool, or relax in the Jacuzzi while enjoying the vibe of cruising upon the Indian Ocean. There are an assortment of other activities and facilities available to keep you entertained too, no matter your age, including the casino, pool games, quizzes, dance lessons, cabaret shows, movies, an aqua park for children and even a midnight buffet to indulge your cravings. -

Prognóstico Das Eleições 2010 Governo Estadual – Senado Federal

Prognóstico das eleições 2010 Governo Estadual – Senado Federal Levantamento preliminar até 1º de julho SBS – Edifício Seguradoras – Salas 301 a 307 CEP: 70093-900 – Brasília-DF Fones: (61) 3225-9704/9744 Fax: (61) 3225-9150 Página: www.diap.org.br E-mail: [email protected] Tendência de eleição para o Senado em 2010 Mandatos encerrados Tendência de eleição Bancada da próxima Partido Bancada Mandatos até 2015 em 2011 em 2010 legislatura (2011-2015) Total 81 54 27 - - PMDB 18 15 3 12 a 14 15 a 17 PSDB 14 9 5 7 a 8 12 a 13 DEM 14 8 6 4 a 5 10 a 11 PT 9 6 3 11 a 13 14 a 16 PTB 7 2 5 0 a 1 5 a 6 PDT 6 4 2 2 a 3 4 a 5 PR 4 3 1 1 a 2 2 a 3 PSB 2 1 1 3 a 4 4 a 5 PRB 2 2 0 0 a 1 0 a 1 PCdoB 1 0 1 0 a 2 1 a 3 PP 1 0 1 1 a 3 2 a 4 PSC 1 1 0 0 a 1 0 a 1 PSOL 1 1 0 0 a 1 0 a 1 PV 1 1 0 0 a 1 0 a 1 PMN 0 0 0 0 a 1 0 a 1 PPS 0 0 0 0 a 1 0 a 1 Legenda para os candidatos ao Senado da República *- DIAP considera o candidato com chance baixa de ser eleito **- DIAP considera o candidato com chance média de ser eleito ***- DIAP considera o candidato com chance alta de ser eleito Senador com mandato até Senador com mandato Principais candidatos Principais candidatos Governador atual 2011/Reeleição até 2015 ao governo ao senado Acre - Binho Marques (PT) - Geraldo Mesquita (PMDB) - - Tião Viana (PT) - Tião Viana (PT) - Edvaldo Magalhães Não - Tião Bocalom (PSDB) (PCdoB)** - Marina Silva (PV) – Não - Jorge Viana (PT)*** - João Correia (PMDB)* - Sergio Petecão (PMN)* Alagoas - Teotônio Vilela Filho - João Tenório (PSDB) – Não - Fernando Collor (PTB) - Ronaldo Lessa -

Brazil @Opendemocracy (2005-15)

Brazil @openDemocracy (2005-15) Fragments of Brazil’s recent political history Arthur Ituassu Reitor Pe. Josafá Carlos de Siqueira SJ Vice-Reitor Pe. Francisco Ivern Simó SJ Vice-Reitor para Assuntos Acadêmicos Prof. José Ricardo Bergmann Vice-Reitor para Assuntos Administrativos Prof. Luiz Carlos Scavarda do Carmo Vice-Reitor para Assuntos Comunitários Prof. Augusto Luiz Duarte Lopes Sampaio Vice-Reitor para Assuntos de Desenvolvimento Prof. Sergio Bruni Decanos Prof. Paulo Fernando Carneiro de Andrade (CTCH) Prof. Luiz Roberto A. Cunha (CCS) Prof. Luiz Alencar Reis da Silva Mello (CTC) Prof. Hilton Augusto Koch (CCBS) Brazil @openDemocracy (2005-15) Fragments of Brazil’s recent political history Arthur Ituassu © Editora PUC-Rio Rua Marquês de S. Vicente, 225 Projeto Comunicar – Casa Agência/Editora Gávea – Rio de Janeiro – RJ – CEP 22451-900 Telefax: (21)3527-1760/1838 [email protected] www.puc-rio.br/editorapucrio Conselho Gestor Augusto Sampaio, Cesar Romero Jacob, Fernando Sá, Hilton Augusto Koch, José Ricardo Bergmann, Luiz Alencar Reis da Silva Mello, Luiz Roberto Cunha, Paulo Fernando Carneiro de Andrade e Sergio Bruni Projeto gráfico José Antonio de Oliveira Foto da capa (detalhe) Marcello Casal Jr/ Agência Brasil (Creative Commons 3.0) Todos os direitos reservados. Nenhuma parte desta obra pode ser reproduzida ou transmitida por quaisquer meios (eletrônico ou mecânico, incluindo fotocópia e gravação) ou arquivada em qualquer sistema ou banco de dados sem permissão escrita da Editora. Este livro não pode ser comercializado. Ituassu, Arthur Brazil @openDemocracy (2005-2015) [recurso eletrônico] : fragaments of Brazil’s recent political history / Arthur Ituassu . – Rio de Janeiro : Ed. PUC-Rio , 2016. -

Annual Report 2015

ANNUAL REPORT 2015 THE BRAZILIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Understand how BNDES works and the results it delivers to society. PERFORMANCE R$ 135.9 billion were disbursed in 954,208 operations with 221,114 clients. Learn about the main activities of infrastructure, social and production inclusion, and in support of the competitiveness of Brazilian companies. INTERNAL ENVIRONMENT Learn more about governance, transparency, relationships, financial sustainability and developing competence at BNDES. ANNUAL REPORT 2015 CONTENTS 4 5 6 12 EDITORIAL BRAZIL AND THE THE BRAZILIAN HOW DOES WORLD IN 2015 DEVELOPMENT BANK FINANCIAL SUPPORT WORK? REGIONAL AND TERRITORIAL DIMENSION INNOVATION 30 36 SOCIAL AND 44 ENVIRONMENTAL BNDES AND SOCIETY STRATEGY AND RESPONSIBILITY INFRASTRUCTURE: VISION FOR A DECISIVE SECTOR THE FUTURE 17 22 26 28 BNDES IN GOVERNANCE, FINANCIAL DEVELOPING NUMBERS CONTROL AND SUSTAINABILITY COMPETENCE MANAGEMENT PRACTICES 49 54 56 58 COMPETITIVENESS SOCIAL AND GLOSSARY/ CREDITS/TELEPHONE OF BRAZILIAN PRODUCTION GRI INDICATOR NUMBERS AND COMPANIES INCLUSION CHART ADDRESSES EDITORIAL This report presents the highlights of our elaboration of a methodology to define PDF version, available on our digital library performance in 2015, focusing on economic, materialities, which is expected to be (www.bndes.gov.br/bibliotecadigital). social and environmental aspects. Starting formalized in 2016. The IR is an international The report ranges from January to out from our capitals – financial, human, initiative aimed at improving the quality December 2015 and comprises the entire intellectual, social and relationship- of corporate reports in an effort towards BNDES System, which includes the Bank’s based, natural and manufactured – and greater transparency and stability in seven facilities – Brasília (Federal District), Rio the prospects that comprise our 2015 the worldwide economic system.