Irish Rugby and the First World War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

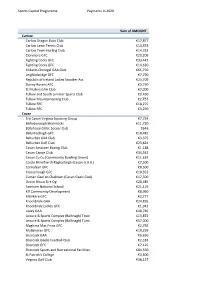

Sports Capital Programme Payments in 2020 Sum of AMOUNT Carlow

Sports Capital Programme Payments in 2020 Sum of AMOUNT Carlow Carlow Dragon Boat Club €17,877 Carlow Lawn Tennis Club €14,353 Carlow Town Hurling Club €14,332 Clonmore GFC €23,209 Fighting Cocks GFC €33,442 Fighting Cocks GFC €14,620 Kildavin Clonegal GAA Club €61,750 Leighlinbridge GFC €7,790 Republic of Ireland Ladies Snooker Ass €23,709 Slaney Rovers AFC €3,750 St Mullins GAA Club €7,000 Tullow and South Leinster Sports Club €9,430 Tullow Mountaineering Club €2,757 Tullow RFC €18,275 Tullow RFC €3,250 Cavan 3rd Cavan Virginia Scouting Group €7,754 Bailieborough Shamrocks €11,720 Ballyhaise Celtic Soccer Club €646 Ballymachugh GFC €10,481 Belturbet GAA Club €3,375 Belturbet Golf Club €23,824 Cavan Amatuer Boxing Club €1,188 Cavan Canoe Club €34,542 Cavan Co Co (Community Bowling Green) €11,624 Coiste Bhreifne Uí Raghaillaigh (Cavan G.A.A.) €7,500 Cornafean GFC €8,500 Crosserlough GFC €10,352 Cuman Gael an Chabhain (Cavan Gaels GAA) €17,500 Droim Dhuin Eire Og €20,485 Farnham National School €21,119 Kill Community Development €8,960 Killinkere GFC €2,777 Knockbride GAA €24,835 Knockbride Ladies GFC €1,942 Lavey GAA €48,785 Leisure & Sports Complex (Ballinagh) Trust €13,872 Leisure & Sports Complex (Ballinagh) Turst €57,000 Maghera Mac Finns GFC €2,792 Mullahoran GFC €10,259 Shercock GAA €6,650 Shercock Gaelic Football Club €2,183 Shercock GFC €7,125 Shercock Sports and Recreational Facilities €84,550 St Patrick's College €3,500 Virginia Golf Club €38,127 Sports Capital Programme Payments in 2020 Virginia Kayak Club €9,633 Cavan Castlerahan -

Pride of the Red Roses

TOUCHLINE The Official Newspaper of The RFU September 2017 Issue 204 BROWN BECOMES RFU CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER JOANNA MANNING-COOPER Steve Brown was appointed RFU Chief Executive Officer at the “His passion for rugby, and his commitment to rugby’s values start of this month after an extensive selection process led by a are obvious to everyone who has worked with him, and he will lead Board Nominations Panel and the approval of the RFU Board. He a strong executive team who are committed to making rugby in began his new role on Monday 4 September England the best in the world. ” Brown was Chief Officer, Business Operations at the RFU, and Before joining the RFU, Brown was UK Finance Director at the UK succeeds Ian Ritchie who announced his retirement earlier this year. operation of Abbott, the global, broad-based health care company, for Steve Brown joined the RFU as Chief Financial Officer on June 10, five years after a decade with the company, covering a number of other 2011. He also served as Managing Director of England Rugby 2015, senior financial positions, including UK Pharmaceutical manufacturing responsible for organising the England 2015 Rugby World Cup, and at Abbott’s Paris-based Commercial Regional Headquarters. widely acclaimed as the most successful Rugby World Cup ever. Prior to joining Abbott, he spent three years as the Business The impact of hosting the event saw the highest annual turnover Support Manager and Group Head of Finance for British Energy in the RFU’s history and record investment in rugby. PLC. He originally trained as an accountant in the National Health He was subsequently appointed RFU Chief Officer, Business Service where he held a number of financial roles. -

Official Handbook 2019/2020 Title Partner Official Kit Partner

OFFICIAL HANDBOOK 2019/2020 TITLE PARTNER OFFICIAL KIT PARTNER PREMIUM PARTNERS PARTNERS & SUPPLIERS MEDIA PARTNERS www.leinsterrugby.ie | From The Ground Up COMMITTEES & ORGANISATIONS OFFICIAL HANDBOOK 2019/2020 Contents Leinster Branch IRFU Past Presidents 2 COMMITTEES & ORGANISATIONS Leinster Branch Officers 3 Message from the President Robert Deacon 4 Message from Bank of Ireland 6 Leinster Branch Staff 8 Executive Committee 10 Branch Committees 14 Schools Committee 16 Womens Committee 17 Junior Committee 18 Youths Committee 19 Referees Committee 20 Leinster Rugby Referees Past Presidents 21 Metro Area Committee 22 Midlands Area Committee 24 North East Area Committee 25 North Midlands Area Committee 26 South East Area Committee 27 Provincial Contacts 29 International Union Contacts 31 Committee Meetings Diary 33 COMPETITION RESULTS European, UK & Ireland 35 Leagues In Leinster, Cups In Leinster 39 Provincial Area Competitions 40 Schools Competitions 43 Age Grade Competitions 44 Womens Competitions 47 Awards Ball 48 Leinster Rugby Charity Partners 50 FIXTURES International 51 Heineken Champions Cup 54 Guinness Pro14, Celtic Cup 57 Leinster League 58 Seconds League 68 Senior League 74 Metro League 76 Energia All Ireland League 89 Energia Womens AIL League 108 CLUB & SCHOOL INFORMATION Club Information 113 Schools Information 156 www.leinsterrugby.ie 1 OFFICIAL HANDBOOK 2019/2020 COMMITTEES & ORGANISATIONS Leinster Branch IRFU Past Presidents 1920-21 Rt. Rev. A.E. Hughes D.D. 1970-71 J.F. Coffey 1921-22 W.A. Daish 1971-72 R. Ganly 1922-23 H.J. Millar 1972-73 A.R. Dawson 1923-24 S.E. Polden 1973-74 M.H. Carroll 1924-25 J.J. Warren 1974-75 W.D. -

Official Handbook 2020/2021 Title Partner Offical Kit Partner

OFFICIAL HANDBOOK 2020/2021 TITLE PARTNER OFFICAL KIT PARTNER PREMIUM PARTNERS PARTNERS & SUPPLIERS MEDIA PARTNERS COMMITTEES & ORGANISATIONS www.leinsterrugby.ie 3 Contents Leinster Branch IRFU Past Presidents 4 COMMITTEES & ORGANISATIONS Leinster Branch Officers 5 Message from the President John Walsh 8 Message from Bank of Ireland 10 Leinster Branch Staff 13 Executive Committee 16 Branch Committees 22 Schools Committee 24 Womens Committee 25 Junior Committee 26 Youths Committee 27 Referees Committee 28 Metro Area Committee 30 Midlands Area Committee 32 North East Area Committee 33 North Midlands Area Committee 34 South East Area Committee 35 Provincial Contacts 39 International Union Contacts 42 Committee Meetings Diary 45 CLUB & SCHOOL INFORMATION Club Information 50 Inclusion Rugby 91 Touring Clubs / Youth Clubs 92 Schools Information 98 OFFICIAL HANDBOOK 2020/2021 COMMITTEES & ORGANISATIONS Leinster Branch IRFU Past Presidents 1920-21 Rt. Rev. A.E. Hughes D.D. 1972-73 A.R. Dawson 1921-22 W.A. Daish 1973-74 M.H. Carroll 1922-23 H.J. Millar 1974-75 W.D. Fraser 1923-24 S.E. Polden 1975-76 F.R. McMullen 1924-25 J.J. Warren 1976-77 P.F. Madigan 1925-26 E.M. Solomons M.A. 1977-78 K.D. Kelleher 1926-27 T.F. Stack 1978-79 I.B. Cairnduff 1927-28 A.D. Clinch M.D. 1979-80 P.J. Bolger 1928-29 W. G Fallon B.L. 1980-81 B. Cross 1929-30 W.H. Acton 1981-82 N.H. Brophy 1930-31 Mr. Justice Cahir Davitt 1982-83 E. Egan 1931-32 A.F. O’Connell 1983-84 P.J. -

KO* HOME AWAY VENUE TOURNAMENT 01-Apr-11 19:05 Ulster

KO* HOME AWAY VENUE TOURNAMENT 01-Apr-11 19:05 Ulster 20-18 Scarlets Ravenhill 01-Apr-11 19:35 Bristol Rugby 14-36 London Welsh Memorial Stadium 01-Apr-11 19:35 Highlanders 26-20 Brumbies Carisbrook, Dunedin 01-Apr-11 19:40 Waratahs 23-16 Chiefs Sydney Football Stadium 01-Apr-11 19:45 Birmingham & Solihull 31-10 Plymouth Albion Damson Park 01-Apr-11 19:45 Connacht 27-23 Edinburgh Sportsground 01-Apr-11 20:45 Perpignan 24-25 Toulouse Stade Aimé Giral 02-Apr-11 14:30 Bayonne 26-16 Racing Métro 92 Stade Jean-Dauger 02-Apr-11 14:30 Bourgoin 27-42 Montpellier Stade Pierre-Rajon 02-Apr-11 14:30 Brive 26-9 La Rochelle Stade Amédée-Domenech 02-Apr-11 14:30 Northampton Saints 53-24 Sale Sharks Franklin's Gardens 02-Apr-11 14:30 Toulon 38-10 Stade Français Stade Mayol 02-Apr-11 15:00 Bedford Blues 31-33 Doncaster Knights Goldington Road 02-Apr-11 15:00 Esher 22-27 Moseley Molesey Road 02-Apr-11 15:00 Gloucester Rugby 34-9 Newcastle Falcons Kingsholm 02-Apr-11 15:00 Lions 25-30 Reds Ellis Park, Johannesburg 02-Apr-11 15:00 Rotherham Titans 16-24 Cornish Pirates Clifton Lane 02-Apr-11 15:00 Worcester Warriors 44-13 Nottingham Sixways 02-Apr-11 15:30 Aironi Rugby 16-17 Glasgow Warriors Stadio Zaffanella 02-Apr-11 16:25 Clermont Auvergne 41-13 Biarritz Olympique Stade Marcel-Michelin 02-Apr-11 17:05 Sharks 6-16 Stormers Kings Park Stadium, Durban 02-Apr-11 17:30 Blues 29-22 Cheetahs Eden Park, Auckland 02-Apr-11 17:30 Harlequins 13-17 Leicester Tigers Twickenham Stoop 02-Apr-11 18:30 Ospreys 21-21 Cardiff Blues Liberty Stadium 02-Apr-11 19:05 Western -

Psni Rugby 04/05

PoliCe SeRviCe of NoRtheRN iRelaNd Rugby Club Fixtures 2010-2011 Newforge Country Club Newforge Lane, Belfast BT9 5NW Telephone (028) 9068 1027 the following are the office Bearers of the iRFU (Ulster Branch) Mr Robert Hunter PSNi Rugby Club for Season 2010/11: Representative PRo Mr Ted Hall President Mr Tim Mairs additional executive Mr Bjorn O’Brien Senior vice President Mr Roy Thompson Committee Members Mr Michael Carson vice Presidents Mr Colin Brunt Mr Mark Sheridan Mr Tim Craig Mr Peter Tees Mr Brian Kenwell Club Medical attendant Mrs Beverley McDowell Mr Robert Hunter Club doctor As approved by the immediate Past President Mr Paul Robinson RUCAA honorary Secretary Mrs Beverley McDowell PSUK Representative Mr Ronnie Carey assistant honorary Secretary Mr Andrew Hamlin irish Police Rugby Mr Tim Mairs Representatives (Co-Chairman) honorary treasurer Mr Brian Kenwell Mr Colin Brunt assistant honorary treasurer Mr Colin Brunt Mr David McBurney Mr Paul Robinson Fixture Secretary Mr Robert Hunter irish Police Rugby head Coach Mr Mervyn Tweed Club Coach Mr David Irwin assistant Coach TBC Club & 1st Xv Captain Mr Andrew McConville 1st Xv vice Captain Mr Andrew Hamlin 2nd Xv Captain Mr Barry Graham PSNI RFC is sponsored by 2nd Xv vice Captain TBC Harp & Crown Credit Union technical director Mr Colin Brunt 1st Xv Managers Mr Paul Hodge Mr David Boyd www.harpandcrowncu.org.uk 2nd Xv Manager Mr Ian Rowan Ulster Rugby Fixtures 20010/11 date time Comp opposition venue Fri 13 Aug 19:30 F Bath Rugby Ravenhill Sat 21 Aug 14:30 F Harlequins The Stoop Thu 26 Aug 19:30 F Leeds Carnegie Ravenhill Fri 3 Sep 19:05 ML Ospreys Ravenhill Sat 11 Sep 19:05 ML Aironi Rugby Stadio Zaffanella Fri 17 Sep 20:05 ML Edinburgh Ravenhill Sat 25 Sep 19:30 ML Connacht Rugby Sportsground Fri 1 Oct 19:05 ML Glasgow Warriors Ravenhill Fri 8 Oct 19:30 HC-P4 Aironi Rugby Ravenhill Sun 17 Oct 16:00 HC-P4 Biarritz Olympique P d Sports Aguilera Pays Basque Fri 22 Oct 19:05 ML Edinburgh Murrayfield Fri 29 Oct 19:05 ML Munster Ravenhill Sun 21 Nov 15:45 ML Cardiff Blues Cardiff City Stad. -

Saca Newsletter

David Boyd set to retire as Rugby Coordinator SACA NEWSLETTER Summer Edition 2016 Joan Kirby Appointed Headmistress It’s been a summer filled with exciting news and achievements both on and off the sporting fields. Ranging from former St. Andrew’s Pupils heading off to the Olympics to current students competing on the international stage in cricket, hockey, chess and many more activities. Before we get into that, the first thing we must do is say a massive congratulations to Joan Kirby who was officially appointed as Headmistress of St. Andrew’s College in June. Well done Joan and we wish you the very best of luck and offer the full support of the Alumni! 2 SACA Newsletter Summer Edition 2016 Welcome Class of 2016 We would also like to say a big welcome to the Class of 2016 who have now officially joined SACA. We hope you got the results you wanted in the Leaving Certifcate and we look forward to seeing you all at future SACA events. The Class of 2016 had their Valedictory Evening at the end of the school year and it was the first year that the Alumni Cups were presented by SACA to the boy and girl who were considered to have con- tributed the most to student life during their time at St Andrew’s. They were presented by SACA presi- dent, Moayyad Kamali to Richard Neville and Sally Barnicle who got involved in absolutely everything from musicals, sport, MUN to Linguistic Olympiads and everything in between. The presentation of the cups was top of the bill just before past pupil, and Sixth Year Head, David Feery wrapped up official proceedings for the Class of 2016. -

Grid Export Data

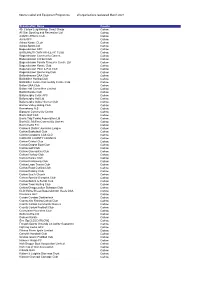

Sports Capital and Equipment Programme all organisations registered March 2021 Organisation Name County 4th Carlow Leighlinbrige Scout Group Carlow All Star Sporting and Recreation Ltd Carlow Ardattin Athletic Club Carlow Asca GFC Carlow Askea Karate CLub Carlow Askea Sports Ltd Carlow Bagenalstown AFC Carlow BAGENALSTOWN ATHLETIC CLUB Carlow Bagenalstown Community Games Carlow Bagenalstown Cricket Club Carlow Bagenalstown Family Resource Centre Ltd Carlow Bagenalstown Karate Club Carlow Bagenalstown Pitch & Putt Club Carlow Bagenalstown Swimming Club Carlow Ballinabranna GAA Club Carlow Ballinkillen Hurling Club Carlow Ballinkillen Lorum Community Centre Club Carlow Ballon GAA Club Carlow Ballon Hall Committee Limited Carlow Ballon Karate Club Carlow Ballymurphy Celtic AFC Carlow Ballymurphy Hall Ltd Carlow Ballymurphy Indoor Soccer Club Carlow Barrow Valley Riding Club Carlow Bennekerry N.S Carlow Bigstone Community Centre Carlow Borris Golf Club Carlow Borris Tidy Towns Association Ltd Carlow Borris/St. Mullins Community Games Carlow Burrin Celtic F.C. Carlow Carlow & District Juveniles League Carlow Carlow Basketball Club Carlow Carlow Carsports Club CLG Carlow CARLOW COUNTY COUNCIL Carlow Carlow Cricket Club Carlow Carlow Dragon Boat Club Carlow Carlow Golf Club Carlow Carlow Gymnastics Club Carlow Carlow Hockey Club Carlow Carlow Karate Club Carlow Carlow Kickboxing Club Carlow Carlow Lawn Tennis Club Carlow Carlow Road Cycling Club Carlow Carlow Rowing Club Carlow Carlow Scot's Church Carlow Carlow Special Olympics Club Carlow Carlow -

Welsh Rugby Union Limited Annual Report 2003-2004 Cymru Am Byth Wales Forever

CYMRU AM BYTH WALES FOREVER WELSH RUGBY UNION LIMITED ANNUAL REPORT 2003-2004 CYMRU AM BYTH WALES FOREVER SSupportupport PPaassssionion IInnonnovvationation RReesspepectct IInsnspirationpiration TTeeamamwwororkk WELSH RUGBY UNION LIMITED ANNUAL REPORT 2003-2004 Contents Officials of the WRU Officials of the WRU 3 Patron Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II President Chairman’s View 5 The Right Honourable Sir Tasker Watkins VC, GBE, DL Board Members of Welsh Rugby Union Chief Executive’s Report 7 David Pickering Chairman Kenneth Hewitt Vice Chairman David Moffett Group Chief Executive WRU General Mal Beynon Martin Davies Manager’s View 9 Geraint Edwards Humphrey Evans Brian Fowler Commercial Report 11 Roy Giddings Russell Howell Peredur Jenkins Millennium Stadium Report 13 Anthony John Alan Jones WRU Chairman David Pickering (right) shaking hands John Jones with Group Chief Executive David Moffett after Financial Report 14 David Rees extending the GCE s contract to 2008 Gareth Thomas Howard Watkins Review of the Season 16 Ray Wilton WRU Executive Board Obituaries 30 David Moffett Group Chief Executive (Chairman) Steve Lewis General Manager WRU Paul Sergeant General Manager Millennium Stadium Accounts 33 Gordon Moodie Group Finance Director (interim - resigned) Gwyn Thomas General Manager Commercial and Marketing Martyn Rees Administration Manager Directorate of Rugby Terry Cobner (Director of Rugby - retired July 04); Steve Hansen (National Coach - Feb 02 - May 04, replaced by Mike Ruddock); Mostyn Richards (Player Development Manager); Leighton Morgan (Coach Development Manager); Rob Yeman (Director of Match Officials) Principal Sub Committees Finance Committee Martin Davies (Chairman), David Pickering, Kenneth Hewitt, David Moffett, Humphrey Evans, John Jones, Group Finance Director Regulatory Committee Russell Howell (Chairman), Mal Beynon, Geraint Edwards, Alan Jones. -

Regulations of the Irish Rugby Football Union 1

REGULATIONS OF THE IRISH RUGBY FOOTBALL UNION 1. General 2. Regulations Governing Matches against Teams from Other Unions 3. Regulations Governing Scratch Teams 4. Regulations Relating to Movement of Individuals between Unions 5. Disciplinary Committees 6. Regulations Relating to the Registration, Eligibility, Movement and Payment of Club Players 7. Regulations Relating to the Irish Exiles 8. Regulations Relating to Anti-Doping and Anti-Corruption 9. The All Ireland League and Cup 10. Regulation Relating to Child Welfare and Protection 11. Regulations Relating to Agents The Committee of the Union has made the following regulations which are binding on all parties affected by these regulations. 1. GENERAL These regulations are supplemental to the regulations relating to the Game made by World Rugby (formerly the International Rugby Board) (World Rugby Regulations) which are binding on the I.R.F.U. and all its members and for greater detail reference should be made to the World Rugby Regulations. Where capitalised words are used in these regulations they shall have the meaning defined in the World Rugby Regulations. 2. REGULATIONS GOVERNING MATCHES AGAINST TEAMS FROM OTHER UNIONS See World Rugby Regulations 16. 2.1 The written consent of the I.R.F.U. must be obtained for the arrangements by Club, School, Branch or Rugby Body affiliated to or recognised by the I.R.F.U. for a visit to any country outside Ireland or for matches in Ireland against a visiting team from such a country. 2.2 In the case of a Club or School, a written application for consent in respect of any such match shall be made to the Branch to which the Club or School is affiliated and subject to approval by such Branch, the Branch shall forward the application to the I.R.F.U. -

Connacht Vs Munster Live Streaming Online Link 3

1 / 5 Connacht Vs Munster Live Streaming Online Link 3 Met Éireann, the Irish National Meteorological Service, is the leading provider of weather information and related services for Ireland.. Dec 8, 2020 — Bord Gais Energy Munster U20 Hurling Semi Final Limerick v Cork, ... Final - Galway v Kilkenny *Full deferred coverage on TG4 at 9.20pm.. 4 days ago — John Andress is now a rugby agent after playing for Exeter, Harlequins, Worcester, Munster, and Connacht. # munster - Saturday 10 July, 2021.. ... online? Why not if you know VIPBOX! Visit VIPBOX and enjoy great number of rugby streams for free! ... HomeRefresh Links. Watch Live rugby Online - HD.. Jun 4, 2021 — Three weeks later the new jersey will be worn for the first time by the ... Munster vs Connacht live streaming & live stream video: Watch .... Ulster win the Ladies title and Munster take the Girls title. 09 July 2015. Google + ... Girls Foursomes, Leinster 3 – Connacht 0.. Leinster GAA Hurling Senior Championship Sat, Jul 3, 2021 Dublin 14:00 ... Live stream On Your PC, Hello Football fans are invited to watch Derry vs .... Roscommon v Galway. Connacht GAA Football Senior Championship Semi-Final. Football. buy now. Saturday 3rd Jul. Limerick v Cork. Munster GAA Hurling Senior .... The official YouTube channel of the United Rugby Championship. ... 3 Minute Highlights: Munster v Connacht | Round 3 | Guinness PRO14 Rainbow Cup. Watch live Rugby HD Stream online. Watch NRL, Super 15, Six Nations, 3 Nations, and Rugby World Cup HD & SD Streams here. Rugby Streaming quality upto 720p.. Sep 29, 2020 — Rugbaí Beo returns to screens on TG4 this coming weekend with three live matches from the Guinness PRO14 featuring Leinster, Munster and ...Thu, Jul 15. -

TT0910-94 TT No.94: Ian Hill

TT0910-94 TT No.94: Ian Hill – Saturday 17th October 2009; Shamrock Rovers v Drogheda United; League of Ireland Premier Division; Score: 2 – 0; Attendance: 2500 (estimate); Admission: 15 euros; Programme 56 pages 4 euros Match rating: 2*. A trip to the new home of Shamrock Rovers, Tallaght Stadium, was my destination for the second game of my trip to Dublin. Earlier in the day I went on the Croke Park Museum and Stadium Tour. I would highly recommend a visit although there is a slightly romanticised view of the GAA and no mention of the previous foreign sports ban! The tour guide was very good and excellent with a group of youngsters who were awe struck by the place. It’s an impressive stadium and I didn’t realise how big a Gaelic Football pitch was until I saw the football equivalent marked out on the turf. The afternoon was spent watching a Rugby Union match between Bective Rangers and Ballymena. This cup tie was played at Donnybrook the former home of the Leinster Rugby Union side. The ground is shared by two clubs – Bective and Old Wesley with each club having its clubhouse at the opposite ends of the ground. The game was an AIB cup game with free admission and free programme it seemed to be an attractive proposition. The programme was excellent – an A5 60-page shell in full colour included a four-page insert featuring the game. I picked mine up in the clubhouse but there were not many about only the insert pages. Did the people of Dublin know something I didn’t? This game was terrible and really painful to watch.