Download (10MB)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Epic Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School May 2017 Modern Mythologies: The picE Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature Sucheta Kanjilal University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Kanjilal, Sucheta, "Modern Mythologies: The pE ic Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature" (2017). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/6875 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Modern Mythologies: The Epic Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature by Sucheta Kanjilal A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a concentration in Literature Department of English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Gurleen Grewal, Ph.D. Gil Ben-Herut, Ph.D. Hunt Hawkins, Ph.D. Quynh Nhu Le, Ph.D. Date of Approval: May 4, 2017 Keywords: South Asian Literature, Epic, Gender, Hinduism Copyright © 2017, Sucheta Kanjilal DEDICATION To my mother: for pencils, erasers, and courage. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS When I was growing up in New Delhi, India in the late 1980s and the early 1990s, my father was writing an English language rock-opera based on the Mahabharata called Jaya, which would be staged in 1997. An upper-middle-class Bengali Brahmin with an English-language based education, my father was as influenced by the mythological tales narrated to him by his grandmother as he was by the musicals of Broadway impressario Andrew Lloyd Webber. -

SHIVAJI UNIVERSITY, KOLHAPUR Provisional Electoral Roll of Registered Graduates

SHIVAJI UNIVERSITY, KOLHAPUR Provisional Electoral Roll of Registered Graduates Polling Center : 1 Kolhapur District - Chh.Shahu Central Institute of Business Education & Research, Kolhapur Faculty - ARTS AND FINE ARTS Sr. No. Name and Address 1 ADAKE VASANT SAKKAPPA uchgaon kolhapur 416005, 2 ADNAIK DEVRAJ KRISHNAT s/o krishnat adnaik ,891,gaalwada ,yevluj,kolhapur., 3 ADNAIK DEVRAJ KRUSHANT Yevluj Panhala, 4 ADNAIK KRISHNAT SHANKAR A/P-KUDITRE,TAL-KARVEER, City- KUDITRE Tal - KARVEER Dist- KOLHAPUR Pin- 416204 5 AIWALE PRAVIN PRAKASH NEAR YASHWANT KILLA KAGAL TAL - KAGAL. DIST - KOLHAPUR PIN - 416216, 6 AJAGEKAR SEEMA SHANTARAM 35/36 Flat No.103, S J Park Apartment, B Ward Jawahar Nagar, Vishwkarma Hsg. Society, Kolhapur, 7 AJINKYA BHARAT MALI Swapnanjali Building Geetanjali Colony, Nigave, Karvir kolhapur, 8 AJREKAR AASHQIN GANI 709 C WARD BAGAWAN GALLI BINDU CHOUK KOLHAPUR., 9 AKULWAR NARAYAN MALLAYA R S NO. 514/4 E ward Shobha-Shanti Residency Kolhapur, 10 ALAVEKAR SONAL SURESH 2420/27 E ward Chavan Galli, Purv Pavellion Ground Shejari Kasb bavda, kolhapur, 11 ALWAD SANGEETA PRADEEP Plot No 1981/6 Surna E Ward Rajarampuri 9th Lane kolhapur, 12 AMANGI ROHIT RAVINDRA UJALAIWADI,KOLHAPUR, 13 AMBI SAVITA NAMDEV 2362 E WARD AMBE GALLI, KASABA BAWADA KOLHPAUR, 14 ANGAJ TEJASVINI TANAJI 591A/2 E word plot no1 Krushnad colony javal kasaba bavada, 15 ANURE SHABIR GUJBAR AP CHIKHALI,TAL KAGAL, City- CHIKALI Tal - KAGAL Dist- KOLHPUR Pin- 416235 16 APARADH DHANANJAY ASHOK E WARD, ULAPE GALLI, KASABA BAWADA, KOLHAPUR., 17 APUGADE RAJENDRA BAJARANG -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

Sant Dnyaneshwar - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Sant Dnyaneshwar - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Sant Dnyaneshwar(1275 – 1296) Sant Dnyaneshwar (or Sant Jñaneshwar) (Marathi: ??? ??????????) is also known as Jñanadeva (Marathi: ????????). He was a 13th century Maharashtrian Hindu saint (Sant - a title by which he is often referred), poet, philosopher and yogi of the Nath tradition whose works Bhavartha Deepika (a commentary on Bhagavad Gita, popularly known as "Dnyaneshwari"), and Amrutanubhav are considered to be milestones in Marathi literature. <b>Traditional History</b> According to Nath tradition Sant Dnyaneshwar was the second of the four children of Vitthal Govind Kulkarni and Rukmini, a pious couple from Apegaon near Paithan on the banks of the river Godavari. Vitthal had studied Vedas and set out on pilgrimages at a young age. In Alandi, about 30 km from Pune, Sidhopant, a local Yajurveda brahmin, was very much impressed with him and Vitthal married his daughter Rukmini. After some time, getting permission from Rukmini, Vitthal went to Kashi(Varanasi in Uttar Pradesh, India), where he met Ramananda Swami and requested to be initiated into sannyas, lying about his marriage. But Ramananda Swami later went to Alandi and, convinced that his student Vitthal was the husband of Rukmini, he returned to Kashi and ordered Vitthal to return home to his family. The couple was excommunicated from the brahmin caste as Vitthal had broken with sannyas, the last of the four ashrams. Four children were born to them; Nivrutti in 1273, Dnyandev (Dnyaneshwar) in 1275, Sopan in 1277 and daughter Mukta in 1279. According to some scholars their birth years are 1268, 1271, 1274, 1277 respectively. -

International Multidisciplinary Research Journal

Vol 4 Issue 9 March 2015 ISSN No :2231-5063 InternationaORIGINALl M ARTICLEultidisciplinary Research Journal Golden Research Thoughts Chief Editor Dr.Tukaram Narayan Shinde Associate Editor Publisher Dr.Rajani Dalvi Mrs.Laxmi Ashok Yakkaldevi Honorary Mr.Ashok Yakkaldevi Welcome to GRT RNI MAHMUL/2011/38595 ISSN No.2231-5063 Golden Research Thoughts Journal is a multidisciplinary research journal, published monthly in English, Hindi & Marathi Language. All research papers submitted to the journal will be double - blind peer reviewed referred by members of the editorial board.Readers will include investigator in universities, research institutes government and industry with research interest in the general subjects. International Advisory Board Flávio de São Pedro Filho Mohammad Hailat Hasan Baktir Federal University of Rondonia, Brazil Dept. of Mathematical Sciences, English Language and Literature University of South Carolina Aiken Department, Kayseri Kamani Perera Regional Center For Strategic Studies, Sri Abdullah Sabbagh Ghayoor Abbas Chotana Lanka Engineering Studies, Sydney Dept of Chemistry, Lahore University of Management Sciences[PK] Janaki Sinnasamy Ecaterina Patrascu Librarian, University of Malaya Spiru Haret University, Bucharest Anna Maria Constantinovici AL. I. Cuza University, Romania Romona Mihaila Loredana Bosca Spiru Haret University, Romania Spiru Haret University, Romania Ilie Pintea, Spiru Haret University, Romania Delia Serbescu Fabricio Moraes de Almeida Spiru Haret University, Bucharest, Federal University of Rondonia, Brazil Xiaohua Yang Romania PhD, USA George - Calin SERITAN Anurag Misra Faculty of Philosophy and Socio-Political ......More DBS College, Kanpur Sciences Al. I. Cuza University, Iasi Titus PopPhD, Partium Christian University, Oradea,Romania Editorial Board Pratap Vyamktrao Naikwade Iresh Swami Rajendra Shendge ASP College Devrukh,Ratnagiri,MS India Ex - VC. -

Bahinabai Chaudhari - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Bahinabai Chaudhari - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Bahinabai Chaudhari(24 August 1880 - 3 December 1951) Bahinabai Chaudhari (Devanagari: ???????? ?????) or Bahinabai Nathuji Chaudhari, was a noted Marathi poetess from Maharashtra, India. Bahinabai was born to a Brahmin family in the village of Aasod in the district of Jalgaon. Her poetry brings alive her surroundings through the Ahirani dialect which is spoken in those parts of the State. Hailing from a farmer’s household, most of her poems are based on farming, land, joy and sorrow of farmers, trees, animals and the nature. Bahina, at the age of 5, was married to a 30-year-old Brahmin, a widower and relative. When she was 9, Bahinabai, her immediate family and her husband had to leave their village because of a family quarrel. After a long journey and two years in a town where her husband performed religious services, the family arrived in the holy city of Kolhapur. There, Bahina heard the devotional verses of the Warkari teacher Tukaram (c.1608-1650), recited not in the Sanskrit of Brahmin worship, but in the vernacular and so accessible to all. This experience was to determine the rest of Bahina's life. Although a member of the highest (Brahmin) caste, she wished to become a follower of Tukaram, of the lowest (Shudra) caste; the wife and daughter of priests committed to upholding the ancient rituals wished to become a devotee who chooses pure devotion over ritual. Following the narrative section of her work are over 350 Abhanga (a kind of devotional verse) on various devotional matters: on the life of bhakti (devotion), on true Brahminism, on the duties of a wife. -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email Id Remarks 9421864344 022 25401313 / 9869262391 Bhaveshwarikar

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 10001 SALPHALE VITTHAL AT POST UMARI (MOTHI) TAL.DIST- Male DEFAULTER SHANKARRAO AKOLA NAME REMOVED 444302 AKOLA MAHARASHTRA 10002 JAGGI RAMANJIT KAUR J.S.JAGGI, GOVIND NAGAR, Male DEFAULTER JASWANT SINGH RAJAPETH, NAME REMOVED AMRAVATI MAHARASHTRA 10003 BAVISKAR DILIP VITHALRAO PLOT NO.2-B, SHIVNAGAR, Male DEFAULTER NR.SHARDA CHOWK, BVS STOP, NAME REMOVED SANGAM TALKIES, NAGPUR MAHARASHTRA 10004 SOMANI VINODKUMAR MAIN ROAD, MANWATH Male 9421864344 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 GOPIKISHAN 431505 PARBHANI Maharashtra 10005 KARMALKAR BHAVESHVARI 11, BHARAT SADAN, 2 ND FLOOR, Female 022 25401313 / bhaveshwarikarmalka@gma NOT RENEW RAVINDRA S.V.ROAD, NAUPADA, THANE 9869262391 il.com (WEST) 400602 THANE Maharashtra 10006 NIRMALKAR DEVENDRA AT- MAREGAON, PO / TA- Male 9423652964 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 VIRUPAKSH MAREGAON, 445303 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10007 PATIL PREMCHANDRA PATIPURA, WARD NO.18, Male DEFAULTER BHALCHANDRA NAME REMOVED 445001 YAVATMAL MAHARASHTRA 10008 KHAN ALIMKHAN SUJATKHAN AT-PO- LADKHED TA- DARWHA Male 9763175228 NOT RENEW 445208 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10009 DHANGAWHAL PLINTH HOUSE, 4/A, DHARTI Male 9422288171 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 SUBHASHKUMAR KHANDU COLONY, NR.G.T.P.STOP, DEOPUR AGRA RD. 424005 DHULE Maharashtra 10010 PATIL SURENDRANATH A/P - PALE KHO. TAL - KALWAN Male 02592 248013 / NOT RENEW DHARMARAJ 9423481207 NASIK Maharashtra 10011 DHANGE PARVEZ ABBAS GREEN ACE RESIDENCY, FLT NO Male 9890207717 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 402, PLOT NO 73/3, 74/3 SEC- 27, SEAWOODS, -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Introduction: Medieval Materials in the Sanskritic Tradition

Part II Introduction: Medieval Materials in the Sanskritic Tradition Ruth Vanita uring the period from approximately the eighth to the eighteenth centuries A.D., Is D lamic culture took root in the Indian subcontinent. Various regional and religious cultures including the Muslim, Buddhist, Jain, and Hindu (Vaishnava, Shaiva, and Shakta) interacted during this period, producing a range of cultural practices that have been highly influential for subsequent periods. Although altered by modern developments during and after the colonial period, many of these practices still exist in recogniz:able form today. Among the texts generated in this period are those in Sanskrit; those in Sanskrit-based lan guages, many of which took on their modern forms at this time; those in the southern Indian languages; and those in the Perso-Arabic and Urdu tradition. In the first three groups, the texts we look at belong to the following major genres: the Puranas, which are collections of re ligious stories, compiled between the fourth and fourteenth centuries; vernacular retellings of the epic and Puranic stories; Katha literature or story cycles; historical chronicles produced in courts; and devotional poetry.! I will here discuss developments of the patterns discussed earlier in the introduction to an cient materials and new developments consequent on the spread of new types of devotion known as Bhakti. Bhakti was a series of movements centered on mystical loving devotion to a 1. For an overview of the literature, see Sukumari Bhattacharji's two books, The Indian Theogony: A Comparative Study ofIndian Mythology from the Vedas to the Puranas (Cam bridge: Cambridge University Press, 1970), and History of Classical Sanskrzt Literature (Hyderabad: Orient Longman, 1993). -

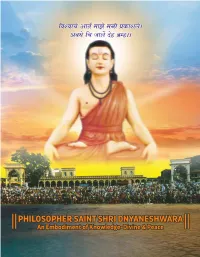

Philosopher Sant Shri Dnyaneshwara

{dídmMo AmV© ‘mPo ‘Zr àH$mebo& AdKo {M Omb| Xoh ~«åh&& PHILOSOPHER SAINT SHRI DNYANESHWARA An Embodiment of Knowledge-Divine & Peace Universal Prayer for Divine Grace World Peace Centre (Alandi) MAEER's MIT, Pune, India (UNESCO Chair for Human Rights, Democracy, Peace & Tolerance) Pasayadan & Dr. Vishwanath Karad MIT World peaceuniversity What the whole world earnestly aspires has dawned in my mind. Therefore my whole existence is now one with the Brahman. Compiled, Edited & Presented by Prof. Dr. Vishwanath D. Karad President, MIT World Peace University Universal Prayer for Divine Grace World Peace Centre (Alandi) MAEER's MIT, Pune, India (UNESCO Chair for Human Rights, Democracy, Peace & Tolerance) Pasayadan & Dr. Vishwanath Karad MIT World peaceuniversity What the whole world earnestly aspires has dawned in my mind. Therefore my whole existence is now one with the Brahman. Compiled, Edited & Presented by Prof. Dr. Vishwanath D. Karad President, MIT World Peace University INDEX PREAMBLE 1 THE LIFE-SKETCH OF PHILOSOPHER SAINT SHRI 13 DNYANESHWARA SANJIVAN SAMADHI OF PHILOSOPHER SAINT SHRI 22 DNYANESHWARA DNYANESHWARA - A POST QUANTUM SCIENTIST AND A 26 SOCIAL REFORMER THE SINE WAVE OF HUMAN LIFE – A Play of Consciousness 30 PHILOSOPHER SAINT SHREE DNYANESHWARA TO ALBERT 38 EINSTEIN THE GREATEST GIFT OF INDIA TO THE WORLD YOGA & AUM 46 (AUM) = E = MC2 - A universal Equation For “transforming the 50 Pilgrim Centers of the world into knowledge centers of the world” PHILOSOPHER SAINT SHRI DNYANESHWARA - AN 58 EMBODIMENT OF SPIRITUAL CONSCIOUSNESS -

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 24/25 | 2020 Hindutva’S Blood 2

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal 24/25 | 2020 The Hindutva Turn: Authoritarianism and Resistance in India Hindutva’s Blood Dwaipayan Banerjee and Jacob Copeman Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/samaj/6657 DOI: 10.4000/samaj.6657 ISSN: 1960-6060 Publisher Association pour la recherche sur l'Asie du Sud (ARAS) Electronic reference Dwaipayan Banerjee and Jacob Copeman, « Hindutva’s Blood », South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal [Online], 24/25 | 2020, Online since 01 November 2020, connection on 15 December 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/samaj/6657 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/samaj.6657 This text was automatically generated on 15 December 2020. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Hindutva’s Blood 1 Hindutva’s Blood Dwaipayan Banerjee and Jacob Copeman 1 Like many other nationalist movements, Hindu nationalism “understand[s] and order[s] the world through ‘cultural essentials’ of religion, blood, and other practices related to the body—food, marriage, death” (Hansen 1999:11). In what follows, we focus particularly on how blood as a political substance of Hindu nationalism congeals ideology in material forms. Specifically, we trace how blood is imagined and exteriorized by Hindutva leaders and adherents: in ideological texts, in donation camps, through the offering of activists’ own blood to political figures, in blood- portraiture of political figures, and in bloodshed during episodes of communal violence. 2 Tracing these imaginations and exteriorizations, we identify three ways in which blood has become a medium and conceptual resource for Hindutva practice. First, we trace how Hindu nationalist ideologues equate blood with the nation’s spatial boundaries, demanding that non-Hindus recognize an ancient, essential blood-tie and assimilate back into the Hindu fold. -

03-Result Rollno

Advertisement No. MAHARASHTRA PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION 03/09/2021 6/2019 MAHARASHTRA CIVIL ENGINEERING SERVICES PRE EXAMINATION - 2020 Page No. 1 LIST OF QUALIFIED CANDIDATES AMRAVATI AM001012 UMEKAR ASHUTOSH VIJAYRAO AM001018 DESHMUKH ARPIT PRAMODRAO AM001080 KATHALE SAURABH NITIN AM001098 Wanode Vishal Anil AM001102 DHIRAJ RAJENDRA TAMGADGE AM001121 DHONDE LALIT MANOJ AM001128 GAWANDE SAURABH JAGANNATH AM001163 NAVDURGE SACHIN RAMESH AM001173 KALE GAYATRI GAJANAN AM001174 GULHANE VAISHNAVI JEEVAN AM001187 POOJARI KARTIK KURMAYYA AM001191 KALE SAURABH RAMESH AM001194 GAWANDE KOMAL WAMANRAO AM001214 UMALE PALLAVI TEJRAO AM001223 HUMANE SWAPNIL PUSHPARAJ AM001224 GHADEKAR SANGHARSH SUNIL AM001257 THAKARE ADESH RAJU AM001261 SHELKE KEDAR AMBADAS AM001264 DHANE GAURAV ARUN AM001277 GAYE JAYESH SUBHASH AM001297 GADE HRUSHIKESH VINOD AM001307 NIRMAL SHRITEJ ASHOK AM001311 DESHMUKH PAYAL PRAMOD AM001360 SHEREKAR VIKRANT VIJAYRAO AM001374 MEKHE ASHISH RAJESH AM001383 DHADVE NIKHIL ASHOK AM001413 JUWAR GAURAV RAJENDRA AM001431 BOKARE LAXMAN CHAMPATRAO AM002006 INGOLE PRATHMESH ARUN AM002050 SUYOG RAMESH BORKAR AM002065 BHOYAR SAGAR EKNATH AM002066 ADSOD AKANKSHA ANIL AM002085 KUMAWAT MUKESHKUMAR RAJENDRAPRASAD AM002100 GAWANDE AKSHAY VINAYAK AM002121 DESHMUKH RASHMI YOGESH AM002122 CHATARKAR MOHAN PURUSHOTTAM AM002141 HOLEY RUGVED RAJKUMAR AM002183 DHAMALE AJAY SANJAY AM002205 BHANGDIA YUDHISHTHIR DILIPKUMAR AM002231 KELO ANIKET SANJAY AM002255 ARBAT ANIKET WASUDEV AM002263 AKSHAY DILIPRAO KOTHE AM002271 NISHANE ABHISHEK PRAKASHRAO AM002281 UKADE