Research on the Relationship Between Story and the Popularity of Animated Movies Meng Wang [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shrek4 Manual.Pdf

Important Health Warning About Playing Video Games Photosensitive Seizures A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed to certain visual images, including fl ashing lights or patterns that may appear in video games. Even people who have no history of seizures or epilepsy may have an undiagnosed condition that can cause these “photosensitive epileptic seizures” while watching video games. These seizures may have a variety of symptoms, including lightheadedness, altered vision, eye or face twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, disorientation, confusion, or momentary loss of awareness. Seizures may also cause loss of consciousness or convulsions that can lead to injury from falling down or striking nearby objects. Immediately stop playing and consult a doctor if you experience any of these symptoms. Parents should watch for or ask their children about the above symptoms— children and teenagers are more likely than adults to experience these seizures. The risk of photosensitive epileptic seizures may be reduced by taking the following precautions: Sit farther from the screen; use a smaller screen; play in a well-lit room; and do not play when you are drowsy or fatigued. If you or any of your relatives have a history of seizures or epilepsy, consult a doctor before playing. ESRB Game Ratings The Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB) ratings are designed to provide consumers, especially parents, with concise, impartial guidance about the age- appropriateness and content of computer and video games. This information can help consumers make informed purchase decisions about which games they deem suitable for their children and families. -

GLAAD Media Institute Began to Track LGBTQ Characters Who Have a Disability

Studio Responsibility IndexDeadline 2021 STUDIO RESPONSIBILITY INDEX 2021 From the desk of the President & CEO, Sarah Kate Ellis In 2013, GLAAD created the Studio Responsibility Index theatrical release windows and studios are testing different (SRI) to track lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and release models and patterns. queer (LGBTQ) inclusion in major studio films and to drive We know for sure the immense power of the theatrical acceptance and meaningful LGBTQ inclusion. To date, experience. Data proves that audiences crave the return we’ve seen and felt the great impact our TV research has to theaters for that communal experience after more than had and its continued impact, driving creators and industry a year of isolation. Nielsen reports that 63 percent of executives to do more and better. After several years of Americans say they are “very or somewhat” eager to go issuing this study, progress presented itself with the release to a movie theater as soon as possible within three months of outstanding movies like Love, Simon, Blockers, and of COVID restrictions being lifted. May polling from movie Rocketman hitting big screens in recent years, and we remain ticket company Fandango found that 96% of 4,000 users hopeful with the announcements of upcoming queer-inclusive surveyed plan to see “multiple movies” in theaters this movies originally set for theatrical distribution in 2020 and summer with 87% listing “going to the movies” as the top beyond. But no one could have predicted the impact of the slot in their summer plans. And, an April poll from Morning COVID-19 global pandemic, and the ways it would uniquely Consult/The Hollywood Reporter found that over 50 percent disrupt and halt the theatrical distribution business these past of respondents would likely purchase a film ticket within a sixteen months. -

Gift Ideas for Evansville Psychiatric Children's Center Christmas 2015

Gift Ideas for Evansville Psychiatric Children’s Center Christmas 2015 For use by all children at EPCC: TV with DVD player Rolling TV table to anchor the TV on (to be able to roll to any location) 10-20 I Pods 20 earbuds/headphones (like Maxwell safe sounds) to use with the Toys for individual kids for Christmas: (Majority Ipods are boys ages 8-12 with 2 I Pads only one girl- 10 years old) DVDs for children’s exercise and yoga Disney Just Dance for Wii or Xbox (any Small lego kits G/Everyone rated games for Wii or Xbox) Hot wheels 5 packs Mind Craft Xbox game Hot Wheels tracks A variety of different board games for the Any type of building toys like K-Nex or other game closet on the dorms and in the family types visit area Nerf balls (Jenga, Yahtzee, Monopoly Jr, Sequence, Action Figures checkers, Star Wars chess game, Brain Imaginex Quest grades 3-6, Taboo, Scrabble, Jr Super Hero mashers Scrabble, Banana Grams, Apples to Apples, Card games Giant Spoons, Would You Rather, Sorry, Journey dolls and Play sets Trouble, Scrabble Jr. Bounce Off, Operation Zoomer dogs and cats Despicable Me 2 Sill Skill game) DinoTrux action vehicles Art and Craft kits- ex. rubber band bracelets, Velvet art posters, melty beads, Alex toys craft kits, etc) **Gift cards to take the children out to eat or to a movie Kinetic Sand and kits Action Figures IMaginex figures Do Not Need list: bicycles, any play weapons of any Play doh kits kind, anything made of glass, no jewelry set that Huffy Green Machine ride have multiple small bead for stringing Skates Basketballs and other sports equipment Building toys Badminton sets . -

Film Rating Release Year a League of Their Own

Film Rating Release Year A League Of Their Own PG 1992 Abominable PG 2019 Anchorman PG-13 2004 Apollo 11 G 2019 Apollo 13 PG 1995 Bee Movie PG 2007 Bernie The Dolphin G 2018 Bill And Ted's Excellent Adventure PG 1989 Bumblebee PG-13 2018 Casper PG 1995 Despicable Me PG 2010 Despicable Me 2 PG 2013 Despicable Me 3 PG 2017 Dirty Dancing PG-13 1987 Dora And The Lost City Of Gold PG 2019 Dr. Seuss' The Lorax PG 2012 Fast And Furious Presents Hobbs And Shaw PG-13 2019 Ferris Bueller's Day Off PG-13 1986 Field Of Dreams PG 1989 Five Feet Apart PG-13 2019 Footloose (1984) PG 1984 Forrest Gump PG-13 1994 Goosebumps PG 2015 Goosebumps 2 - Haunted Halloween PG 2018 Grease PG 1978 Groundhog Day PG 1993 Home (2015) PG 2015 Hook PG 1991 Hop PG 2011 How To Train Your Dragon PG 2010 How To Train Your Dragon The Hidden World PG 2019 How To Train Your Dragon 2 PG 2014 I Can Only Imagine PG 2018 Indiana Jones And The Last Crusade PG-13 1989 Instant Family PG-13 2018 Jurassic Park PG-13 1993 Knives Out (2019) PG-13 2019 Kung Fu Panda PG 2008 La La Land PG-13 2016 Labyrinth PG 1986 Madagascar PG 2005 Madagascar 3: Europe's Most Wanted PG 2012 Mamma Mia PG-13 2008 Mamma Mia Here We Go Again PG-13 2018 Matilda (1996) PG 1996 Megamind PG 2010 Men In Black (1997) PG-13 1997 Men In Black International PG-13 2019 Monster House PG 2006 Monsters Vs. -

SHREK the MUSICAL Official Broadway Study Guide CONTENTS

WRITTEN BY MARK PALMER DIRECTOR OF LEARNING, CREATIVE AND MEDIA WIldERN SCHOOL, SOUTHAMPTON WITH AddITIONAL MATERIAL BY MICHAEL NAYLOR AND SUE MACCIA FROM SHREK THE MUSICAL OFFICIAL BROADWAY STUDY GUIDE CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 Welcome to the SHREK THE MUSICAL Education Pack! A SHREK CHRONOLOGY 4 A timeline of the development of Shrek from book to film to musical. SynoPsis 5 A summary of the events of SHREK THE MUSICAL. Production 6 Interviews with members of the creative team of SHREK THE MUSICAL. Fairy Tales 8 An opportunity for students to explore the genre of Fairy Tales. Feelings 9 Exploring some of the hang-ups of characters in SHREK THE MUSICAL. let your Freak flag fly 10 Opportunities for students to consider the themes and characters in SHREK THE MUSICAL. One-UPmanshiP 11 Activities that explore the idea of exaggerated claims and counter-claims. PoWer 12 Activities that encourage students to be able to argue both sides of a controversial topic. CamPaign 13 Exploring the concept of campaigning and the elements that make a campaign successful. Categories 14 Activities that explore the segregation of different groups of people. Difference 15 Exploring and celebrating differences in the classroom. Protest 16 Looking at historical protesters and the way that they made their voices heard. AccePtance 17 Learning to accept ourselves and each other as we are. FURTHER INFORMATION 18 Books, CD’s, DVD’s and web links to help in your teaching of SHREK THE MUSICAL. ResourceS 19 Photocopiable resources repeated here. INTRODUCTION Welcome to the Education Pack for SHREK THE MUSICAL! Increasingly movies are inspiring West End and Broadway shows, and the Shrek series, based on the William Steig book, already has four feature films, two Christmas specials, a Halloween special and 4D special, in theme parks around the world under its belt. -

Shrek Jr. Cast and Crew List!

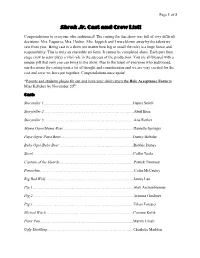

Page 1 of 3 Shrek Jr. Cast and Crew List! Congratulations to everyone who auditioned! The casting for this show was full of very difficult decisions. Mrs. Esquerra, Mrs. Hosker, Mrs. Joppich and I were blown away by the talent we saw from you. Being cast in a show (no matter how big or small the role) is a huge honor and responsibility. This is truly an ensemble art form. It cannot be completed alone. Each part from stage crew to actor plays a vital role in the success of the production. You are all blessed with a unique gift that only you can bring to the show. Due to the talent of everyone who auditioned, our decisions for casting took a lot of thought and consideration and we are very excited for the cast and crew we have put together. Congratulations once again! *Parents and students please fill out and have your child return the Role Acceptance Form to Miss Kelleher by November 20th. Cast: Storyteller 1……………………………………………………….…..Hanna Smith Storyteller 2………………………………………………………...….Abril Brea Storyteller 3……………………………..……………………..………Ana Rother Mama Ogre/Mama Bear………………………….………………...…Danielle Springer Papa Ogre/ Papa Bear……………………………………………..…Danny Boboltz Baby Ogre/Baby Bear ………………………………...…….………...Robbie Dubay Shrek…………………………………………………………….....….Collin Toole Captain of the Guards………………………………………….…...…Patrick Twomey Pinocchio……………………………………………………………....Colin McCauley Big Bad Wolf………………………………………………….….…....James Lau Pig 1……………………………………………………………….......Alex Aschenbrenner Pig 2…………………………………………………………….…......Arianna Gardiner Pig 3………………………………………………………….......……Ethan -

ALPHABETICAL LIST of Dvds and Vts 9/6/2011 DVD a Mighty Heart

ALPHABETICAL LIST OF DVDs AND VTs 9/6/2011 DVD A Mighty Heart: Story of Daniel Pearl A Nurse I am – Documentary and educational film about nurses A Single Man –with Colin Firth and Julianne Moore (R) Abe and the Amazing Promise: a lesson in Patience (VeggieTales) Akeelah and the Bee August Rush - with Freddie Highmore, Keri Russell, Jonathan Rhys Meyers, Terrence Howard, Robin Williams Australia - with Hugh Jackman, Nicole Kidman Aviator (story of Howard Hughes - with Leonardo DiCaprio Because of Winn-Dixie Beethoven - with Charles Grodin, Bonnie Hunt Big Red Black Beauty Cats & Dogs Changeling - with Angelina Jolie Charlie and the Chocolate Factory - with Johnny Depp Charlie Wilson’s War - with Tom Hanks, Julie Roerts, Phil Seymour Hoffman Charlotte’s Web Chicago Chocolat - with Juliette Binoche, Judi Dench, Alfred Molina, Lena Olin & Johnny Depp Christmas Blessing - with Neal Patrick Harris Close Encounters of the Third Kind – with Richard Dreyfuss Date Night – with Steve Carell and Tina Fey (PG-13) Dear John – with Channing Tatum and Amanda Seyfried (PG-13) Doctor Zhivago Dune Duplicity - with Julia Roberts and Clive Owen Enchanted Evita Finding Nemo Finding Neverland Fireproof – with Kirk Cameron on Erin Bethea (PG) Five People You Meet in Heaven Fluke Girl With a Pearl Earring – with Colin Firth, Scarlett Johannson, Tom Wilkinson Grand Torino (with Clint Eastwood) Green Zone – with Matt Damon (R) Happy Feet Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince Hildalgo with Viggo Mortensen (PG13) Holiday, The – with Cameron Diaz, Kate Winslet, -

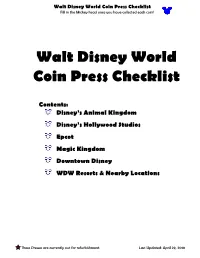

Walt Disney World Coin Press Checklist Fill in the Mickey Head Once You Have Collected Each Coin!

Walt Disney World Coin Press Checklist Fill in the Mickey head once you have collected each coin! Walt Disney World Coin Press Checklist Contents: Disney’s Animal Kingdom Disney’s Hollywood Studios Epcot Magic Kingdom Downtown Disney WDW Resorts & Nearby Locations These Presses are currently out for refurbishment. Last Updated: April 29, 2010 Walt Disney World Coin Press Checklist Fill in the Mickey head once you have collected each coin! Out of the Wild #1 Lion King 5 of 7, Rafiki Celebrate Culture South Africa Tarzan 7 of 8, Jane & Tarzan The Outpost Shop #1 Penny Presses Jungle Book 6 of 6, Share Khan Beastly Bazaar Safari Minnie Mouse Tarzan 4 of 8, Tantor Safari Pluto Lion King 3 of 7, Hula Timon Safari Goofy The Outpost Shop #2 Stink Bug Chester & Hester's Dinosaur Treasures #1 Tarzan 8 of 8, Jane Iguanodon Lion King 1 of 7, Simba Camtaurus Alioramus Rainforest Café #1 Hot Air Balloon, Orlando, FL Chester & Hester's Dinosaur Treasures #2 Mockingbird, Florida State Bird Tarzan 3 of 8, Terk Crab w/ Sunglasses, Orlando, FL Mickey with Fossil Alligator, Orlando, FL Lion King 6 of 7, Scar Restaurantosaurus #1 Dawa Bar Styracosaurus Lion Saltasaurus Hippopotamus Ankylosaurus Rhino Restaurantosaurus #2 Duka La Filimu #1 Tarzan 1 of 8, Tarzan & Jane Safari Mickey Duckosaurus Donald Safari Donald Dinosaur Skeleton Safari Goofy Wildlife Express Train Station #1 Duka La Filimu #2 Tarzan 2 of 8, Swinging Tarzan Safari Minnie Tarzan 5 of 8, Professor Safari Pooh Lion King 4 of 7, Pumba Safari Tigger Island Mercantile #1 Festival of The Lion -

Cars Tangled Finding Nemo Wreck It Ralph Peter Pan Frozen Toy Story Monsters Inc. Snow White Alice in Wonderland the Little Merm

FRIDAY, APRIL 3RD – DISNEY DAY… AT HOME! Activity 1: • Disney Pictionary: o Put Disney movies and character names onto little pieces of paper and fold them in half o Put all of the pieces of paper into a bowl o Then draw it for their team to guess Can add a charade element to it rather than drawing if that is preferred o If there are enough people playing, you can make teams • Here are some ideas, you can print these off and cut them out or create your own list! Cars Tangled Finding Nemo Wreck It Ralph Peter Pan Frozen Toy Story Monsters Inc. Snow White Alice in Wonderland The Little Mermaid Up Brave Robin Hood Aladdin Cinderella Sleeping Beauty The Emperor’s New Groove The Jungle Book The Lion King Beauty and the Beast The Princess and the Frog 101 Dalmatians Lady and the Tramp A Bug’s Life The Fox and the Hound Mulan Tarzan The Sword and the Stone The Incredibles The Rescuers Bambi Fantasia Dumbo Pinocchio Lilo and Stitch Chicken Little Bolt Pocahontas The Hunchback of Notre Wall-E Hercules Dame Mickey Mouse Minnie Mouse Goofy Donald Duck Sully Captain Hook Ariel Ursula Maleficent FRIDAY, APRIL 3RD – DISNEY DAY… AT HOME! The Genie Simba Belle Buzz Lightyear Woody Mike Wasowski Cruella De Ville Olaf Anna Princess Jasmine Lightning McQueen Elsa Activity 2: • Disney Who Am I: o Have each family member write the name of a Disney character on a sticky note. Don’t let others see what you have written down. o Take your sticky note and put it on another family members back. -

Awards & Nominations

VICKI HIATT MUSIC SUPERVISOR / EDITOR AWARDS & NOMINATIONS GOLDEN REEL AWARD ALI NOMINATION (2001) Best Sound Editing -Music, Feature Film, Domestic and Foreign GOLDEN REEL AWARD THE ROAD TO EL DORADO NOMINATION (2000) Best Sound Editing-Music, Animation FEATURE FILM THE ARK & THE AARDVARK Keith Kjarvak, Kurt Rauer, prod. Unified Pictures John Stevenson, dir. Music Editor HOTEL TRANSYLVANIA 3 Michelle Murdocca, prod. Sony Pictures Animation Gendy Tartakovsy, dir. Music Editor SURF’S UP 2: WAVEMANIA Toby Chu, Composer Sony Pictures Animation Michelle Wong, prod. Music Editor Henry Wu, dir. HALF MAGIC Alex Wurman, Composer Magic Bubble Productions Bill Sheinberg, prod. Music Consultant Heather Graham, dir. HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON 3 John Powell, Composer DreamWorks Animation Bonnie Arnold, prod. Music Editor Dean DeBlois, dir. LIFE BRIEFLY Tom Howe, Composer Thousand Dream Prods. Erika Armin, James Brubaker, prods. Music Editor Dan Ireland, dir. EMOJI Michelle Raimo, prod. Sony Pictures Animation Anthony Leondis, dir. Music Editor BOSS BABY Denise Nolan Cascino, Ramsey Ann Naito, prods. DreamWorks Animation Tom McGrath, dir. Music Editor The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 1 VICKI HIATT MUSIC SUPERVISOR / EDITOR INDISCRETION Toby Chu, Composer Granfallon Productions Alexandra Baranska, Thomas Beach, Laura Boersma, prods. Music Supervisor John Stewart Muller, dir. SO B. IT Nick Urata, Composer Branded Pictures J. Todd Harris, Orien Richman, prods. Music Supervisor Stephen Gyllenhaal, dir. CAPTAIN UNDERPANTS Teddy Shapiro, Composer DreamWorks Animation Mark Swift, prod. Music Editor David Soren, dir. TROLLS Christophe Beck, Composer DreamWorks Animation Gina Shay, prod. Music Editor Mike Mitchell, dir. FLAWED DOGS Berkeley Breathed, exec. prod. DreamWorks Animation Noah Baumbauch, dir. -

Animation Stagnation Or: How America Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Mouse by Billy Tooma

Animation Stagnation or: How America Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Mouse by Billy Tooma With all the animated flms that come out reason behind this is that Disney just keeps these days, it can actually be somewhat difcult putting out one hit after another and audiences to distinguish a Disney-made one from the expect perfection each time. Unfortunately, for others, seeing as how the competition tries on a the company that has made Mickey Mouse a consistent basis to copy the style that Walt Disney household name for over 90 years, that isn’t the himself unofcially trademarked as far back as case. Even though people are showing up to the the late 1920s. Te very thought that something cinemas, they aren’t doing it because they expect is being put out by Disney can lead to biased to see a screen gem. Tey’re doing it because appeal. In 1994, Warner Bros. had produced an it’s felt that they owe something, possibly their animated feature entitled Tumbelina. In one childhood, to Disney. But, does that mean of its frst test screenings, the overall audience people are being foolish for constantly shelling consensus was low, discouraging the executives out money to see a Disney animated flm every because they felt theirs was as fne a product as year or so? Te answer is ‘no,’ because Disney their competition. In an unprecedented move, was able to gain such an early monopoly on Warner Bros. stripped their logo from the flm’s the industry that it allowed them to prevent opening and replaced it with the Disney one. -

Video Game Trader Magazine & Price Guide

Winter 2009/2010 Issue #14 4 Trading Thoughts 20 Hidden Gems Blue‘s Journey (Neo Geo) Video Game Flashback Dragon‘s Lair (NES) Hidden Gems 8 NES Archives p. 20 19 Page Turners Wrecking Crew Vintage Games 9 Retro Reviews 40 Made in Japan Coin-Op.TV Volume 2 (DVD) Twinkle Star Sprites Alf (Sega Master System) VectrexMad! AutoFire Dongle (Vectrex) 41 Video Game Programming ROM Hacking Part 2 11Homebrew Reviews Ultimate Frogger Championship (NES) 42 Six Feet Under Phantasm (Atari 2600) Accessories Mad Bodies (Atari Jaguar) 44 Just 4 Qix Qix 46 Press Start Comic Michael Thomasson’s Just 4 Qix 5 Bubsy: What Could Possibly Go Wrong? p. 44 6 Spike: Alive and Well in the land of Vectors 14 Special Book Preview: Classic Home Video Games (1985-1988) 43 Token Appreciation Altered Beast 22 Prices for popular consoles from the Atari 2600 Six Feet Under to Sony PlayStation. Now includes 3DO & Complete p. 42 Game Lists! Advertise with Video Game Trader! Multiple run discounts of up to 25% apply THIS ISSUES CONTRIBUTORS: when you run your ad for consecutive Dustin Gulley Brett Weiss Ad Deadlines are 12 Noon Eastern months. Email for full details or visit our ad- Jim Combs Pat “Coldguy” December 1, 2009 (for Issue #15 Spring vertising page on videogametrader.com. Kevin H Gerard Buchko 2010) Agents J & K Dick Ward February 1, 2009(for Issue #16 Summer Video Game Trader can help create your ad- Michael Thomasson John Hancock 2010) vertisement. Email us with your requirements for a price quote. P. Ian Nicholson Peter G NEW!! Low, Full Color, Advertising Rates!