Report on Regional Social Inclusion Plans and Programs in Slovakia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Data Specification on Administrative Units – Guidelines

INSPIRE Infrastructure for Spatial Information in Europe D2.8.I.4 INSPIRE Data Specification on Administrative units – Guidelines Title D2.8.I.4 INSPIRE Data Specification on Administrative units – Guidelines Creator INSPIRE Thematic Working Group Administrative units Date 2009-09-07 Subject INSPIRE Data Specification for the spatial data theme Administrative units Publisher INSPIRE Thematic Working Group Administrative units Type Text Description This document describes the INSPIRE Data Specification for the theme Administrative units Contributor Members of the INSPIRE Thematic Working Group Administrative units Format Portable Document Format (pdf) Source Rights public Identifier INSPIRE_DataSpecification_AU_v3.0.pdf Language En Relation Directive 2007/2/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 March 2007 establishing an Infrastructure for Spatial Information in the European Community (INSPIRE) Coverage Project duration INSPIRE Reference: INSPIRE_DataSpecification_AU_v3.0.docpdf TWG-AU Data Specification on Administrative units 2009-09-07 Page II Foreword How to read the document? This guideline describes the INSPIRE Data Specification on Administrative units as developed by the Thematic Working Group Administrative units using both natural and a conceptual schema languages. The data specification is based on the agreed common INSPIRE data specification template. The guideline contains detailed technical documentation of the data specification highlighting the mandatory and the recommended elements related to the implementation of INSPIRE. The technical provisions and the underlying concepts are often illustrated by examples. Smaller examples are within the text of the specification, while longer explanatory examples are attached in the annexes. The technical details are expected to be of prime interest to those organisations that are/will be responsible for implementing INSPIRE within the field of Administrative units. -

Potential and Central Forms of Tourism in 21 Regions of Slovakia

Potential and Central Forms of Tourism in 21 Regions of Slovakia Importance and development priorities of regions The following previews list short characteristics of individual regions in terms of their current state, development possibilities and specific needs. The previews include a list of the most important destinations in the individual regions, the infrastructure that needs to be completed and the anticipated environmental impacts on tourism in the region. These lists are not entirely comprehensive and only include the main elements that create the character of the region as a tourist destination. 1. Bratislava Region Category / relevance Medium-term perspective International Long-term perspective International Sub-region, specific Medium-term perspective - Small Carpathians sub-region (viniculture) location - Bratislava - Senec Long-term perspective - Strip along the right bank of the Danube Type of tourism Long-term incoming foreign tourism over 50%; intensive domestic tourism as well Stay tourism – short-term in incoming as well as in domestic tourism Long–stay waterside tourism only in the summer time; one-day visits – domestic as well as foreign tourism. Transit Forms of tourism - Sightseeing tourism - Business tourism - Summer waterside stays Activities with the - Discovering cultural heritage – Business tourism - Congress/conference tourism – highest long-term Visiting cultural and sport events – Stays/recreation near water – Water sports – Boat potential sports and water tourism - Cycle tourism Position on the Slovak Number -

Tourism Development Options in Marginal and Less-Favored Regions: a Case Study of Slovakia´S Gemer Region

land Article Tourism Development Options in Marginal and Less-Favored Regions: A Case Study of Slovakia´s Gemer Region Daniela Hutárová, Ivana Kozelová and Jana Špulerová * Institute of Landscape Ecology of Slovak Academy of Sciences, P.O. Box 254, Štefánikova 3, 814 99 Bratislava, Slovakia; [email protected] (D.H.); [email protected] (I.K.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +421-2-32293628 Abstract: Marginal and less-favored regions are characterized by negative migration balance, lower living standards, aging of the population, a lower number of employment opportunities, lower educational level, and lower investments in the territory. Gemer is one of these regions in Slovakia. On the other hand, the Gemer region has a very interesting history and many cultural monuments, nature protection areas, and UNESCO World Heritage sites that create options for tourism develop- ment. The monuments of the Gothic Road have the potential for religious tourism. Karst relief and the sites and monuments related to mining present on the Iron Road provide suitable conditions for geotourism and mining tourism. Local villages contain traditional agricultural landscapes, which create suitable conditions for active rural tourism associated with creative tourism or agrotourism. There is also the promising possibility of cross-border cooperation with Hungary. However, the revenues from tourism do not reach the same level as in other, similar regions of Slovakia. The main failings of tourism development include the insufficient coordination of destination marketing organization stakeholders, lack of care for monuments, and underestimation of the potential of Roma culture and art production. However, analyzed state policy instruments on the promotion of tourism Citation: Hutárová, D.; Kozelová, I.; did not mitigate but rather exacerbated regional disparities in Slovakia. -

Regional DISPARITIES in the SLOVAK REPUBLIC from the POINT of VIEW of STRUCTURAL EMPLOYMENT

DOI: 10.2478/aree-2014-0006 Zuzana POLÁKOVÁ, Zlata SOJKOVÁ, Peter OBTULOvič Acta regionalia et environmentalica 1/2014 Acta regionalia et environmentalica 1 Nitra, Slovaca Universitas Agriculturae Nitriae, 2014, p. 30–35 REGIONAL DISPARITIES IN THE SLOVAK REPUBLIC FROM THE POINT OF VIEW OF STRUCTURAL EMPLOYMENT Zuzana POLÁkoVÁ*, Zlata SOJKOVÁ, Peter ObtuLOVIč Slovak University of Agriculture in Nitra, Slovak Republic Recently, much attention has been paid to the topic of employment in Slovakia and regional disparities. The aim of this paper is, on the basis of available data from regional databases and through the use of appropriate methodological apparatus, to draw attention to the development of Slovak regions’ structural employment proportion on the total employment according to the sectors of agriculture, industry, construction and services in the time period from 2004 to 2012. The article examined the similarity of regions in terms of structural employment through cluster analysis at NUTS 2 level. Counties are grouped into four mutually similar clusters. Keywords: employment, region, disparity The overall situation in the labour market is affected by experiencing a migration loss. On the other hand, there is the labour supply which is conditioned by development an increasing migration to the Bratislava region. Nižňanský and non-economic factors (demographic and social ones (2007) stresses that economic development and thereby in particular). Another factor affecting the labour market solution of regional disparities between regions and also situation is demand for labour, which is determined by within regions is not a task for the national governments technological and economic implications arising from the primarily. The approach is different in different countries and use of labour in combination with other production factors. -

Czech and Slovak

LETTER-WRITING GUIDE Czech and Slovak INTRODUCTION Republic, the library has vital records from only a few German-speaking communities. Use the This guide is for researchers who do not speak Family History Library Catalog to determine what Czech or Slovak but must write to the Czech records are available through the Family History Republic or Slovakia (two countries formerly Library and the Family History Centers. If united as Czechoslovakia) for genealogical records are available from the library, it is usually records. It includes a form for requesting faster and more productive to search these first. genealogical records. If the records you want are not available through The Republic of Czechoslovakia was created in the Family History Library, you can use this guide 1918 from parts of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. to help you write to an archive to obtain From Austria it included the Czech provinces of information. Bohemia, Moravia, and most of Austrian Silesia. From Hungary it included the northern area, which BEFORE YOU WRITE was inhabited primarily by Slovaks. The original union also included the northeastern corner of Before you write a letter to the Czech Republic or Hungary, which was inhabited mainly by Slovakia to obtain family history information, you Ukrainians (also called Ruthenians), but this area, should do three things: called Sub-Carpathian Russia, was ceded to the Soviet Republic of Ukraine in 1945. Since 1993, C Determine exactly where your ancestor was the Czech Republic and Slovakia have been two born, was married, resided, or died. Because independent republics with their own governments. most genealogical records were kept locally, you will need to know the specific locality where your ancestor was born, was married, resided for a given time, or died. -

Introduction 1. Conceptual Frameworks of the Research

Linguistic and ethnic border changes: within the frames of Ister-Granum Euroregion settlement group György FARKAS Abstract The main objective of the study is to clarify the context of a data analysis with ethnic geographical approach, namely how the increased crossing traffic through the rebuilding Mária Valéria Bridge is reflected in the ethnic composition of the given Slovakian settlements. The spatial structure analyzes the direction and depth of the changes that are reflected through the three-decade nationality statistics. The study applies a set of concepts of ethnic geography and it explores the changes within the ethnic block zones and the Hungarian-Slovak linguistic boundaries in the region. Keywords: Mária Valéria Bridge, ethnic structure of population, assimilation, ethnic geography, spatial structure analysis, ethnic blocks, changes of linguistic borders Introduction This study is based on official data about the social changes of the past 20 years, and it attempts to provide a reliable basis to assess the question whether the observable ethnic changes within the settlements that are influenced by the significant developments in infrastructure before and after the reconstruction of the Mária Valéria Bridge, may be interpreted as indicators of changes that may lead to the relatively fast and profound rearrangement of the region’s ethnic spatial structure. 1. Conceptual frameworks of the research 1.1 Literary background This study is mainly based on the theoretical approaches, definitions, methodology, hypotheses and case studies that reflect the Southern-Slovakian region, namely the ethnic structure model of the Levice District developed and defended in the dissertation thesis in 2003, at Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest, Faculty of Science, Doctoral School of Earth Sciences.1 The study aims to answer the identified and articulated primary question. -

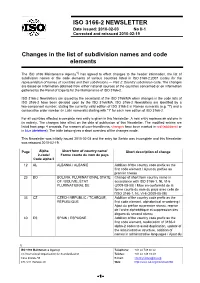

ISO 3166-2 NEWSLETTER Changes in the List of Subdivision Names And

ISO 3166-2 NEWSLETTER Date issued: 2010-02-03 No II-1 Corrected and reissued 2010-02-19 Changes in the list of subdivision names and code elements The ISO 3166 Maintenance Agency1) has agreed to effect changes to the header information, the list of subdivision names or the code elements of various countries listed in ISO 3166-2:2007 Codes for the representation of names of countries and their subdivisions — Part 2: Country subdivision code. The changes are based on information obtained from either national sources of the countries concerned or on information gathered by the Panel of Experts for the Maintenance of ISO 3166-2. ISO 3166-2 Newsletters are issued by the secretariat of the ISO 3166/MA when changes in the code lists of ISO 3166-2 have been decided upon by the ISO 3166/MA. ISO 3166-2 Newsletters are identified by a two-component number, stating the currently valid edition of ISO 3166-2 in Roman numerals (e.g. "I") and a consecutive order number (in Latin numerals) starting with "1" for each new edition of ISO 3166-2. For all countries affected a complete new entry is given in this Newsletter. A new entry replaces an old one in its entirety. The changes take effect on the date of publication of this Newsletter. The modified entries are listed from page 4 onwards. For reasons of user-friendliness, changes have been marked in red (additions) or in blue (deletions). The table below gives a short overview of the changes made. This Newsletter was initially issued 2010-02-03 and the entry for Serbia was incomplete and this Newsletter was reissued 2010-02-19. -

Routing of Vegetable Production in the Nitra Region in 2002–2010

DOI: 10.2478/ahr-2014-0007 Magdaléna VALšÍKOVÁ, Rudolf RYBAN, Katarína SRNIčKOVÁ Acta horticulturae et regiotecturae 1/2014 Acta horticulturae et regiotecturae 1 Nitra, Slovaca Universitas Agriculturae Nitriae, 2014, p. 24–28 ROUTING OF VEGETABLE PRODUCTION IN THE NITRA REGION IN 2002–2010 Magdaléna ValšÍkovÁ*, Rudolf RYban, Katarína SrničkovÁ Slovak University of Agriculture in Nitra, Slovak Republic The paper deals with the evaluation of the development of cultivation area and production of vegetables in different districts of the Nitra region in the period of the years 2002–2010. The region of Nitra has excellent climatic conditions for the cultivation of agricultural crops, including vegetables. Among the most widely grown vegetables belong cabbage, carrots, parsley, onions, tomatoes, peppers, red watermelons, and sweet corn. Keywords: vegetables, production, area The Nitra region covers an area of 6,343 km2, occupying in the districts of Komárno and Nové Zámky. There was 12.9% of the area of Slovakia. In the region there are 350 593 ha of vegetables grown in the Nitra district (Meravá municipalities, 15 of which have city status. The county is et al., 2011). divided into seven districts, namely: Komárno, Levice, Nitra, The greatest volume of vegetables was produced in the Nové Zámky, Šaľa, Topoľčany, and Zlaté Moravce. The largest district of Levice (7,343 t), followed by the Nové Zámky of them is the Levice district, and conversely the smallest district (7,114 t) and the district of Komárno (4,538 t). The one is the Šaľa district. district of Šaľa produced 2,775 t, the district of Nitra 2,091 t of The land relief of the region is flat, punctuated by vegetables. -

Administrace Okres Kraj Územní Oblast Abertamy Karlovy Vary Karlovarský Kraj Plzeň Adamov Blansko Jihomoravský Kraj Brno Ad

Administrace Okres Kraj Územní oblast Abertamy Karlovy Vary Karlovarský kraj Plzeň Adamov Blansko Jihomoravský kraj Brno Adamov České Budějovice Jihočeský kraj České Budějovice Adamov Kutná Hora Středočeský kraj Trutnov Adršpach Náchod Královéhradecký kraj Trutnov Albrechtice Karviná Moravskoslezský kraj Ostrava Albrechtice Ústí nad Orlicí Pardubický kraj Jeseník Albrechtice nad Orlicí Rychnov nad Kněžnou Královéhradecký kraj Trutnov Albrechtice nad Vltavou Písek Jihočeský kraj České Budějovice Albrechtice v Jizerských horách Jablonec nad Nisou Liberecký kraj Trutnov Albrechtičky Nový Jičín Moravskoslezský kraj Ostrava Alojzov Prostějov Olomoucký kraj Brno Andělská Hora Bruntál Moravskoslezský kraj Jeseník Andělská Hora Karlovy Vary Karlovarský kraj Plzeň Anenská Studánka Ústí nad Orlicí Pardubický kraj Jeseník Archlebov Hodonín Jihomoravský kraj Brno Arneštovice Pelhřimov Vysočina Jihlava Arnolec Jihlava Vysočina Jihlava Arnoltice Děčín Ústecký kraj Ústí nad Labem Aš Cheb Karlovarský kraj Plzeň Babice Hradec Králové Královéhradecký kraj Trutnov Babice Olomouc Olomoucký kraj Jeseník Babice Praha-východ Středočeský kraj Praha Babice Prachatice Jihočeský kraj České Budějovice Babice Třebíč Vysočina Jihlava Babice Uherské Hradiště Zlínský kraj Zlín Babice nad Svitavou Brno-venkov Jihomoravský kraj Brno Babice u Rosic Brno-venkov Jihomoravský kraj Brno Babylon Domažlice Plzeňský kraj Plzeň Bácovice Pelhřimov Vysočina Jihlava Bačalky Jičín Královéhradecký kraj Trutnov Bačetín Rychnov nad Kněžnou Královéhradecký kraj Trutnov Bačice Třebíč Vysočina -

THAISZIA Introduced Tree Species Survey and Their Representation In

Thaiszia - J. Bot., Košice, 22 (2): 201-210, 2012 http://www.bz.upjs.sk/thaiszia THAISZIAT H A I S Z I A JOURNAL OF BOTANY Introduced tree species survey and their representation in the park objects of Levice district TIBOR BEN ČAŤ, IVICA KOVÁ ČOVÁ , JURAJ MODRANSKÝ & DUŠAN DANIŠ Department of Landscape Planning and Design, FEE, Technical University in Zvolen, T. G. Masaryka 24, SK-960 53 Zvolen, Slovakia; [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Ben čať T., Ková čová I., Modranský J. & Daniš D. (2012): Introduced tree species survey and their representation in the park objects of Levice district. – Thaiszia – J. Bot. 22 (2): 201-210. – ISSN 1210-0420. Abstract: The park and non-park objects in 90 settlements of Levice district were searched. Together 70 objects situated in 48 settlements (villages or towns) were found during inventory of woody species in May – September 2011. The results showed that in 90 settlements of Levice district there are situated 70 park and non-park objects. The total number of woody species fluctuated between 4 and 111 pieces, in Čajkov park and Levice city park, respectively. The percentage of introduced, autochthonous, broadleaves and coniferous woody taxa was also determined. In the studied objects there dominated mostly introduced woody taxa and broadleaves.. Keywords: introduced tree species, park objects, Levice, inventory Introduction All forms of greenery have positive influence on people and his environment. In the past and also nowadays, introduced tree species have been used within greenery design because of their significant aesthetic and hygienic aspect and colour variegation. -

Prívalové Povodne V Povodiach Hrona, Ipľa a Slanej V Máji a Júni 2013

Slovenský hydrometeorologický ústav Odbor Centrum predpovedí a výstrah Banská Bystrica Prívalové povodne v povodiach Hrona, Ipľa a Slanej v máji a júni 2013 SLOVENSKÝ HYDROMETEOROLOGICKÝ ÚSTAV Centrum predpovedí a výstrah Odbor Centrum predpovedí a výstrah Banská Bystrica Prívalové povodne v povodiach Hrona, Ipľa a Slanej v máji a júni 2013 Banská Bystrica, január 2013 Obrázok na titulnej strane: pri sútoku Kamenistého potoka s Čiernym Hronom 25.6.2013, autor RNDr. Jana Podolinská Obsah 1. ÚVOD ................................................................................................................................... 4 2. METEOROLOGICKÁ SITUÁCIA ............................................................................................ 4 3. ZRÁŽKY .............................................................................................................................. 6 4. HYDROLOGICKÁ SITUÁCIA ................................................................................................. 9 5. VÝSTRAHY ........................................................................................................................ 13 6. ZÁVER ............................................................................................................................... 13 3 1. Úvod Prvý polrok roku 2013 sa vyznačoval veľkou priestorovou variabilitou úhrnov atmosférických zrážok. Celkový úhrn zrážok sa za prvý polrok na niektorých miestach Slovenska pohyboval na úrovni ročného normálu, ojedinele ho aj prekročil, čo sa prejavilo aj na -

The Evolution of the Party Systems of the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic After the Disintegration of Czechoslovakia

DOI : 10.14746/pp.2017.22.4.10 Krzysztof KOŹBIAŁ Jagiellonian University in Crakow The evolution of the party systems of the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic after the disintegration of Czechoslovakia. Comparative analysis Abstract: After the breaking the monopoly of the Communist Party’s a formation of two independent systems – the Czech and Slovakian – has began in this still joint country. The specificity of the party scene in the Czech Republic is reflected by the strength of the Communist Party. The specificity in Slovakia is support for extreme parties, especially among the youngest voters. In Slovakia a multi-party system has been established with one dominant party (HZDS, Smer later). In the Czech Republic former two-block system (1996–2013) was undergone fragmentation after the election in 2013. Comparing the party systems of the two countries one should emphasize the roles played by the leaders of the different groups, in Slovakia shows clearly distinguishing features, as both V. Mečiar and R. Fico, in Czech Republic only V. Klaus. Key words: Czech Republic, Slovakia, party system, desintegration of Czechoslovakia he break-up of Czechoslovakia, and the emergence of two independent states: the TCzech Republic and the Slovak Republic, meant the need for the formation of the political systems of the new republics. The party systems constituted a consequential part of the new systems. The development of these political systems was characterized by both similarities and differences, primarily due to all the internal factors. The author’s hypothesis is that firstly, the existence of the Hungarian minority within the framework of the Slovak Republic significantly determined the development of the party system in the country, while the factors of this kind do not occur in the Czech Re- public.