Krause 2015 Playing the Victim Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Safety Sensitive Personnel Certifications As of 8/1/2021

SAFETY SENSITIVE PERSONNEL CERTIFICATIONS AS OF 9/1/2021 YEAR CERTIFICATION NAME CERT. NO. ISSUED TYPE NOEL D. BISHOP II SSP 15614 2016 Safety Sensitive Personnel WAYNE D. COSNER SSP 23902 2020 Safety Sensitive Personnel SCOTT A. CRAWFORD SSP 20766 2018 Safety Sensitive Personnel JORDAN A. HORN SSP 18556 2017 Safety Sensitive Personnel SHAWN M. LESHER SSP 18417 2017 Safety Sensitive Personnel BRYCEN J. LIPPS SSP 25646 2021 Safety Sensitive Personnel KEVIN L. MIDKIFF SSP 18080 2017 Safety Sensitive Personnel JUSTIN L. RIFFLE SSP 16427 2016 Safety Sensitive Personnel JOSE L. RODRIGUEZ SSP 23906 2020 Safety Sensitive Personnel WESLEY A. SPAID SSP 17347 2017 Safety Sensitive Personnel CODY J. STOOTS SSP 18378 2017 Safety Sensitive Personnel ANTHONY S. TOLER SSP 16188 2016 Safety Sensitive Personnel JEREMIAH A. YOUNG SSP 17404 2017 Safety Sensitive Personnel JOHN J. AALMO SSP 16511 2016 Safety Sensitive Personnel GREGORY M. AARON SSP 16941 2017 Safety Sensitive Personnel AHMED AASIM SSP 7934 2013 Safety Sensitive Personnel JAMES B. ABBEY SSP 20504 2018 Safety Sensitive Personnel ASHLEY N. ABBOTT SSP 6530 2013 Safety Sensitive Personnel JEFFREY L. ABBOTT SSP 9908 2014 Safety Sensitive Personnel MERCY V. ABBOTT SSP 4985 2013 Safety Sensitive Personnel PAUL A. ABBOTT SSP 15850 2016 Safety Sensitive Personnel STEVEN S. ABBOTT SSP 294 2013 Safety Sensitive Personnel STEVEN S. ABBOTT SSP 295 2013 Safety Sensitive Personnel VALERIE A. ABBOTT SSP 1265 2013 Safety Sensitive Personnel CHARLES E. ABBOTT, JR. SSP 7420 2013 Safety Sensitive Personnel MATEEN J. ABDUL-AZIZ SSP 12190 2014 Safety Sensitive Personnel CHRISTOPHER A. ABE SSP 13825 2015 Safety Sensitive Personnel KENT B. -

Ilwu/Pma Joint Disclaimer Los Angeles / Long Beach Casual Processing List

ILWU/PMA JOINT DISCLAIMER LOS ANGELES / LONG BEACH CASUAL PROCESSING LIST Attached is the List of those selected in the February 7, 2017 through March 29, 2017 random draw for potential processing toward Identified Casual status in the Port of Los Angeles/Long Beach. The List will be used in sequence to fill Los Angeles/Long Beach’s need for new casuals. The Joint Port Labor Relations Committee (JPLRC) shall immediately process all ranked applicants from the list after which the list shall be terminated. Any names not initially drawn shall be purged from the process and individuals shall have no rights to consideration for casual application but shall be afforded equal opportunity with others, should a new list be established. Those to whom processing may be offered will be contacted if and when they will be offered testing for potential casual work. Candidates who satisfy all screening and testing requirements will become eligible for placement on the Identified Casual List from which longshore work is dispatched. Make sure you read and understand the full Disclaimer stated below. Submitting a postcard, interest card, or application, having a card selected in a draw, having a card sequenced and placed on a posted List, being contacted for testing/processing, and the stated procedures for casual processing do not offer or guarantee processing, employment or continued employment, particular procedures (including testing or retesting) or promotion. No reliance should be placed upon any of these steps, none of which forms a contract or creates any binding obligations upon PMA or ILWU towards you. The parties to the governing collective bargaining agreement (the “Pacific Coast Longshore Contract Document,” PCLCD), through the JPLRCs may, by joint agreement and in their discretion, at any time without notice, change or revoke the procedures for hiring, promotion, and employment in the longshore industry. -

Baby Boy Names Registered in 2011

Page 1 of 39 Baby Boy Names Registered in 2011 # Baby Boy Names # Baby Boy Names # Baby Boy Names 1 Aaban 1 Abdulmajeed 2 Achilles 1 Aadarsh 1 Abdulqadir 1 Adael 1 Aadhil 1 Abdulqaioom 129 Adam 1 Aadhiteya 1 Abdulqudus 1 Adan 1 Aadhya 1 Abdulrahman 1 Adar 1 Aadineer 1 Abdul-Rehman 5 Addison 1 Aadon 1 Abdulsalam 1 Adeel 1 Aagman 1 Abdurahman 1 Adeer 1 Aahaan 2 Abdurrahman 1 Adel 3 Aahil 1 AbdurRahman 2 Adem 1 Aaiden 1 Abdusalam 1 Ademide 1 Aakesh 4 Abe 1 Aden 6 Aarav 1 Abeil 2 Adesh 1 Aaren 10 Abel 1 Adhiraj 1 Aaric 4 Abhay 1 Adhum 1 Aarik 1 Abhaydeep 1 Adi 1 Aariz 1 Abhayjeet 1 Adiel-Aky 64 Aaron 1 Abhayveer 4 Adil 1 Aarsh 1 Abhijit 1 Adin 5 Aaryan 4 Abhijot 1 Adiraj 4 Aayan 1 Abhimanyu 1 Aditya 1 Aazmir 4 Abhinav 1 Adjiot 1 Abas 1 Abhir 1 Adlee 5 Abbas 2 Abijot 1 Adler 1 Abd 1 Abinaash 1 Adley 1 Abdallah 1 Abir 1 Admir 1 Abdalrahman 1 Abishai 2 Adnan 1 Abdalrhman 1 Able 1 Adolf 3 Abdel 2 Abner 1 Adon 1 Abdelaziz 1 Abot 1 Adonias 1 Abdelhamid 7 Abraham 2 Adonis 1 Abdelkareem 5 Abram 1 Ador 1 Abdelmajid 1 Abraz 49 Adrian 1 Abdelnasir 1 Abryel 2 Adriano 1 Abdelrahman 1 Abshir 3 Adriel 2 Abdelrhman 1 Abu 3 Adrien 1 Abdi 1 Abubakar 1 Adriene 1 Abdifatah 1 AbuBakr 1 Advait 5 Abdirahman 1 Abubakr 2 Adyaan 1 Abdisamad 1 Abui 1 Aeber 1 Abdu 1 Abukar 3 Aedan 7 Abdul 1 Acacsio 2 Aeden 1 Abdulahi 3 Ace 1 Aeolus 1 Abdulaziz 1 Aceel 1 Aerius 1 Abdul-Aziz 1 Acely 1 Aeron 1 Abdulbaki 1 Acer 1 Aerren 1 Abdulkareem 1 Acesin 1 Aeshaan 17 Abdullah 1 Acesyn 1 Aeska 3 Abdullahi 1 Aceyn 1 Aeson 1 Abdullha-Khalil 1 Achakh 1 Aevriel Page 2 of 39 Baby Boy Names -

Fathers and Sons Who Have Played Pro Football

Fathers and Sons Who Have Played Pro Football 217 documented sets of father-sons who have played pro football (List Includes Players from AAFC, AFL and NFL) * Active during the 2014 Season ADAMLE BELSER Tony – LB, FB – 1947-1951, 1954 Cleveland Browns Caesar – DB – 1968-1971 Kansas City Chiefs, 1974 San Francisco Mike – RB – 1971-72 Kansas City Chiefs, 1973-74 New York Jets, 49ers 1975-76 Chicago Bears Jason – DB – 1992-2000 Indianapolis Colts, 2001-02 Kansas City Chiefs ADAMS Sam – G – 1972-1980 New England Patriots, 1981 New Orleans BERCICH Saints Bob – S – 1960-1961 Dallas Cowboys Sam – DT – 1994-99 Seattle Seahawks, 2000-01 Baltimore Pete – LB – 1995-98, 2000 Minnesota Vikings Ravens, 2002 Oakland Raiders, 2003-05 Buffalo Bills, 2006 Cincinnati Bengals, 2007 Denver Broncos BETTRIDGE John – FB, LB – 1937 Chicago Bears, 1937 Cleveland Rams ADAMS Ed – LB – 1964 Cleveland Browns Julius – DE – 1971-1985, 1987 New England Patriots Keith – LB – 2001-02 Dallas Cowboys, 2002-05 Philadelphia BLADES Eagles, 2006 Miami Dolphins, 2007 Cleveland Browns Bennie – DB – 1988-1996 Detroit Lions, 1997 Seattle Seahawks H.B. – ILB – 2007-2010 Washington Redskins ALAMA-FRANCIS Joe – QB – 1958-1959 Green Bay Packers BOSTIC Ikaika – DE – 2007-2009 Detroit Lions, 2009-2011 Miami Dolphins JOHN – DB – 1985-87 Detroit Lions *JON – LB – 2013-present Chicago Bears ALDRIDGE Allen – DE – 1967-1970 CFL, 1971-72 Houston Oilers, BRADLEY 1974 Cleveland Browns Ed – G, DE – 1950, 1952 Chicago Bears Allen – LB - 1994-97 Denver Broncos, 1998-2001 Detroit Lions Ed – LB – -

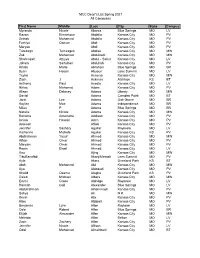

MCC Dean's List Spring 2021 All Campuses First Name Middle Last

MCC Dean's List Spring 2021 All Campuses First Name Middle Last City State Campus Myranda Nicole Abarca Blue Springs MO LV Razan Elmamoun Abdalla Kansas City MO PV Zeinab Mohamed Abdalla Kansas City MO PV Farhiya Osman Abdi Kansas City MO PV Maryan Abdi Kansas City MO PV Tarekegn Temesgen Abdisa Kansas City MO MW Zak Mohamed Abdukadir Kansas City MO MW Shafeeqah Attiyya Abdul - Sabur Kansas City MO LV Johara Saifulbarr Abdullah Kansas City MO PV Kristin Marie Abraham Blue Springs MO BR Byan Hasan Abuoun Lees Summit MO LV Tayler Accurso Kansas City MO MW Zach J Ackman Atchison KS BT Anthony Paul Acosta Kansas City MO LV Ikhlas Mahamat Adam Kansas City MO PV Alison Delaney Adams Liberty MO MW David Adams Camden Point MO BT Jaret Lee Adams Oak Grove MO BR Kaylee Mae Adams Independence MO BR Miles P Adams Blue Springs MO BR Natalie Nicole Adams Kansas City MO MW Ronisha Antoinette Addison Kansas City MO PV Isnino Hassan Aden Kansas City MO PV Ameneh Aflaki Kansas City MO PV Jennifer Sashary Aguilar Raymore MO LV Katherine Michele Aguilar Kansas City KS PV Abdirahman Yusuf Ahmed Kansas City MO MW Aihan Omer Ahmed Kansas City MO PV Maryam Omar Ahmed Kansas City MO PV Reem Elsafi Ahmed Kansas City MO LV Kau Ajing Kansas City MO MW TikuBanaNdi AkanjiMesack Lees Summit MO PV Kyle Akers Overland Park KS BT Abdi Mohamed Akil Kansas City MO MW Aya Alaboudi Kansas City MO PV Khalid Osama Alagha Overland Park KS PV Caleb Michael Albers Kansas City MO MW Emmi Grace Aldridge Raymore MO LV Hannah Gail Alexander Blue Springs MO LV Abdulrahman Alhammadi -

Name List for Firefighter on June 26, 2012. the List Is Based on Exam 2000, Which Was Held from March 17 to April 20, 2012

The Department of Citywide Administrative Services established a 40,976- name list for Firefighter on June 26, 2012. The list is based on Exam 2000, which was held from March 17 to April 20, 2012. Readers should note that eligible lists change over their four-year life as candidates are added, removed, reinstated, or rescored. The list shown below is accurate as of the date of establishment but list standings can change as a result of appeals. Some names are prefixed by the letters v, d, p, s and r. The letter “v” designates a credit given to an honorably discharged veteran who has served during time of war. The letter “d” designates a credit given to an honorably discharged veteran who was disabled in combat. The letter “p” designates a “legacy credit” for a candidate whose parent died while engaged in the discharge of duties as a NYC Police Officer or Firefighter. The letter “r” indicates that five points were added to the final score of a candidate for being a resident of New York City. Finally, the letter “s” designates a “legacy credit” for being the sibling of a Police Officer or Firefighter who was killed in the World Trade Center attack on Sept. 11, 2001. 2000 FIREFIGHTER 1.0 D S R JAVIER A VASQUEZ 118 2.0 V P R MICHAEL ESPOSITO 116 3.0 V P R PATRICK K DOWDELL 113 4.0 D R JOSEPH P TRYNOSKY 113 5.0 D R NADER N ARKADAN 113 6.0 D P S R AGUSTIN J VILLALOBOS 113 7.0 P R ANTHONY MENDEZ 113 8.0 P S ERICK A GONZALEZ 112 8.5 D R ROBERT L SCHENKER 112 9.0 P R JOHN C FISCHER 112 10.0 S R RANDELL S REYES 112 10.5 P R CHRISTOPHER J WIEBER 112 -

Tournament Brackets Team Photos & Rosters Past Tournament Resuts

2016 Basketball 3A/4A Tournament Brackets Team Photos & Rosters Past Tournament Resuts For more information and stats go to www.asaa.org Welcome to March Madness March 24, 2016 Dear Attendees and Participants, Welcome to the 2016 Alaska School Activities Association March Madness 3A and 4A Alaska State Basketball Championships! This tournament creates a wonderful platform for young athletes from all around the state to showcase their skills, practice team work, and enjoy some friendly competition. I am sure everyone has worked very hard to get here, and I appreciate the principles of teamwork and sportsmanship that are promoted in team sports. I encourage each of the athletes to carry those ideals into their daily lives and set a high standard for their peers. I have fond memories of playing in state basketball tournaments as a Valdez Buccaneer while in high school. This year’s tournament is sure to be an enjoyable event that you will remember for many years as well, and I wish each team the best for a successful, memorable, and safe competition. Sincerely, Bill Walker Governor On behalf of the Alaska School Activities Association Board of Directors and ASAA’s corporate partners, welcome to the 2016 First National Bank Alaska State High School March Madness Basketball Championships! Student-athletes, we applaud your dedication to doing your best for yourself and for your school. Coaches, counselors and parents, thank you for continuing to support interscholastic sports and activities. And, to the spectators, we appreciate your being part -

AUSTIN PEAY (16-7, 10-0) at TENNESSEE STATE (14-9, 6-4) SCHEDULE FEBRUARY 6, 2020 ■ GENTRY CENTER ■ NASHVILLE, TENN

COLBY WILSON BASKETBALL CONTACT E: [email protected] P: 615-604-3803 GOVERNORS BASKETBALL | 13-TIME OHIO VALLEY CONFERENCE CHAMPION | 2019 OVC PRESEASON PLAYER OF THE YEAR 2019-20 GAME NOTES | THE TENNESSEE STATE REMATCH AUSTIN PEAY (16-7, 10-0) at TENNESSEE STATE (14-9, 6-4) SCHEDULE FEBRUARY 6, 2020 ■ GENTRY CENTER ■ NASHVILLE, TENN. DATE OPPONENT TIME FASTBREAK Nov. 5 Oakland City W, 110-67 THE MATCHUP Nov. 9 at Western Kentucky L, 75-97 • Austin Peay State University men’s basketball team Vanderbilt Invitational (Campus Sites) is set for the return trip to the Nashville pairing of the Ohio Valley Conference, beginning with a 7:30 Nov. 16 at Tulsa L, 65-72 p.m., Thursday rematch with Tennessee State at Nov. 20 at Vanderbilt L, 72-90 Nov. 23 Southeastern Louisiana W, 81-60 the Gentry Center. Nov. 25 South Carolina State W, 92-66 • After his season’s seventh 30-point night, with 37 against Tennessee State in the previous meeting on Dec. 3 at Arkansas L, 61-69 January 23, Terry Taylor is now the nation’s eighth- Dec. 7 North Florida W, 90-83 AUSTIN TENNESSEE leading scorer at 22.1 points per game; no Gov has Dec. 12 at West Virginia L, 53-84 PEAY STATE Dec. 17 McKendree W, 80-61 2019-20 RECORD averaged better than 22 points per game for a season 2019-20 RECORD St. Pete Shootout (Eckerd College) 16-7 ■ 10-0 OVC 14-9 ■ 6-4 OVC since Nick Stapleton (23.1 ppg) in 2001-02, which Dec. -

Run Date: 12/19/16 12Th District Court Page: 1 312 S

RUN DATE: 12/19/16 12TH DISTRICT COURT PAGE: 1 312 S. JACKSON STREET JACKSON MI 49201 OUTSTANDING WARRANTS STATUS -WRNT NAME CUR CHARGE C/M/F DOB WARRANT DT ABBAS MIAN/ZAHEE OVER CMV V C 1/01/1961 12/28/2012 ABDON ALLAN/LEE NO VALID L M 7/09/1950 12/28/2001 ABDULLAH BERNADETTE NO VALID L M 10/21/1982 2/05/2014 ABREGO ANDREW/ REGISTRATI C 7/07/1974 12/15/2016 ABREGO ANDREW/ NO PROOF I C 7/07/1974 12/15/2016 ABSTON CHERICE/KI SUSPEND OP M 9/06/1968 7/22/2016 ACKERMAN KATHERINE/ LARCENY M 5/04/1977 3/19/2013 ACKLEY FRANK/JOSE SUSPEND OP M 1/07/1981 11/14/2008 ACKLEY FRANK/JOSE OWI M 1/07/1981 11/16/2015 ACKLEY FRANK/JOSE POSS OF MJ M 1/07/1981 11/16/2015 ACKLEY FRANK/JOSE PARAPHERNA M 1/07/1981 11/16/2015 ACKLEY FRANK/JOSE NO OPS POS M 1/07/1981 11/16/2015 ACKLEY FRANK/JOSE OWVI-ALCOH M 1/07/1981 11/14/2008 ACKLEY FRANK/JOSE DOM VIOLEN M 1/07/1981 9/05/2012 ACKLEY FRANK/JOSE DWLS 2ND O M 1/07/1981 11/14/2008 ACKLEY FRANKY/JOS ASSAULT/BA M 9/24/1996 9/19/2016 ACKLEY FRANKY/JOS MDOP M 9/24/1996 9/19/2016 ADAMCZYK JENNIFER/L IMPR PLATE M 10/26/1982 6/02/2016 ADAMCZYK JENNIFER/L DISORDERLY M 10/26/1982 4/12/2016 ADAMS AMANDA/JO IMPR PLATE M 4/11/1986 12/13/2016 ADAMS BARBARA/GA RETAIL FRA M 8/13/1973 11/17/1999 ADAMS CHASITY/LE NO OPS POS M 7/07/1979 12/27/2001 ADAMS DANA/ANNET FALSE PRET M 4/08/1985 10/22/2014 ADAMS JAMIE/ELAI NO VALID L M 4/10/1978 3/09/2012 ADAMS KATHERINE/ IMPR PLATE M 12/27/1987 9/15/2016 ADAMS MARY/ANN NO VALID L M 12/05/1961 1/21/2016 ADAMS MARY/ANN SPD 13 OVE C 12/05/1961 1/21/2016 ADAMS MARY/ANN RETAIL FRA M 12/05/1961 -

Daily Releases February 1, 2019 0 0 First Name Middle Name Type Of

Daily Releases February 1, 2019 0 0 First Name Middle NameType of Release Released From Highest Felony Class 244486 Watkins Willie Eugene Mandatory Reentry Supervision - In State Fulton County Jail Class D (1 - 5 years) 281438 West Tommy Mandatory Reentry Supervision - In State Roederer Corr. Complex Class C (5 - 10 years) 219118 Jackson Montas Loray Mandatory Reentry Supervision - In State Roederer Assessment Cntr Class D (1 - 5 years) 199990 Blair Joseph Discharged - Not Specified Roederer Assessment Cntr Class D (1 - 5 years) 213182 WestmorlandDonald Glenn Discharged (by SOCD Completion) - Not SpecifiedLee Adjustment Center Class C (5 - 10 years) 268208 HollingsworthRondall Mandatory Reentry Supervision - In State Little Sandy Corr. Complex Class C (5 - 10 years) 206094 Gofourth Christopher Discharged - Administrative Minimum Expiration Little Sandy Corr. Complex Class D (1 - 5 years) 290288 Hobbs DeVonte' Martez Mandatory Reentry Supervision - In State Little Sandy Corr. Complex Class C (5 - 10 years) 257549 Armstrong Jeffery Mandatory Reentry Supervision - In State Little Sandy Corr. Complex Class C (5 - 10 years) 288809 Wilson Tony L Mandatory Reentry Supervision - In State Little Sandy Corr. Complex Class C (5 - 10 years) 188254 Brown Christopher Dale Mandatory Reentry Supervision - In State Eastern KY Corr. Complex Class C (5 - 10 years) 195375 Reed Javon Mandatory Reentry Supervision - In State Eastern KY Corr. Complex Class C (5 - 10 years) 286606 Collett Charles E Mandatory Reentry Supervision - In State Eastern KY Corr. Complex Class C (5 - 10 years) 185993 Tungate Danny Randall Mandatory Reentry Supervision - In State Eastern KY Corr. Complex Class C (5 - 10 years) 219230 Moss Antonio M Mandatory Reentry Supervision - In State Eastern KY Corr. -

Redactedcopy Youngkinlist V7

Case Number Report Date Agency Name Agency Case Number Offense County Offense Date Individual Type GAR-1511-12179 11/13/2015 RICHARDSON PD 201500122862 Dallas 10/30/2015 Abbey, Neneh Suspect GAR-1309-11553 10/08/2013 MESQUITE PD 13094887 Dallas 09/07/2013 Abdeljaleel, Kamel Suspect GAR-1402-02171 03/17/2014 MESQUITE PD 14016896 Dallas 02/18/2014 Abdeljaleel, Kamel Suspect GAR-1509-10116 09/30/2015 MESQUITE PD 15087681 Dallas 09/13/2015 Abonsa, Hugo Suspect GAR-1608-10770 09/23/2016 MESQUITE PD 16087080 Dallas 08/27/2016 Acosta Cota, Adrian Suspect GAR-1608-10770 09/23/2016 MESQUITE PD 16087080 Dallas 08/27/2016 Acosta Cota, Adrian Suspect GAR-1309-11554 10/08/2013 MESQUITE PD 13094957 Dallas 09/08/2013 Acosta, Feliciano Suspect GAR-1512-14234 01/14/2016 MESQUITE PD 15124120 Dallas 12/26/2015 Acosta, Ofelia Suspect GAR-1510-11608 11/02/2015 RICHARDSON PD 201500116147 Dallas 10/16/2015 Acosta, Saul Suspect GAR-1412-13619 01/13/2015 MESQUITE PD 14120924 Dallas 12/06/2014 Acri, Mark Suspect GAR-1605-06500 06/14/2016 MESQUITE PD 16050959 Dallas 05/22/2016 Acuenteco-Martinez, Emiliano Suspect GAR-1605-06500 06/14/2016 MESQUITE PD 16050959 Dallas 05/22/2016 Acuenteco-Martinez, Emiliano Suspect GAR-1502-02200 03/27/2015 MESQUITE PD 15016612 Dallas 02/19/2015 Acy, Billy Suspect GAR-1608-10342 09/09/2016 LANCASTER PD 16003949 Dallas 08/07/2016 Adams, Alcus Suspect GAR-1504-04816 05/27/2015 MESQUITE PD 15038065 Dallas 04/25/2015 Adams, Micah Suspect GAR-1606-07069 06/28/2016 PLANO THP TX4MN70UMW03 Dallas 06/04/2016 Adams, Stanley Suspect GAR-1408-09012 -

Continued to June 30, 2021

RUN DATE: 02/06/21 PAGE 1 IN THE GENERAL COURT OF JUSTICE LOCATION: LILLINGTON, NC DISTRICT COURT DIVISION COUNTY OF HARNETT COURT DATE: 03/03/21 TIME: 09:00 AM COURTROOM NUMBER: 0002 HARNETT COUNTY CRIMINAL DISTRIT DISPOSITION COURT JUDGE PRESIDING : COURTROOM CLERK : PROSECUTOR : : : : : NO. FILE NUMBER DEFENDANT NAME COMPLAINANT ATTORNEY CONT ************************************************************************************* 1 20CR 704113 ABNER,IJESTER,LEE,III JACOBS,Z,J DPD (T)SPEEDING 064/35 PLEA: VER: 91549G4 CLS:3 P: L: JUDGMENT: 2 20CR 706269 ABRAMS,MICHELLE,MITCH FARMER,K,F SHP (T)SPEEDING 073/55 PLEA: VER: 300071G CLS:3 P: L: JUDGMENT: 3 20CR 705897 ABREU,LAWRENCE,MARTIN HIGH,T,C SHP 1 (T)DWLR NOT IMPAIRED REV PLEA: VER: 311446G CLS:3 P: L: JUDGMENT: 4 21IF 700324 ACOSTA-NAJMEH,RICARDO COLE,E,T DPD AKA: ACOSTA,RICARDO , NAJMEH,RICARDO (I)SPEEDING 045/35 PLEA: VER: 785329G JUDGMENT: 5 20CR 705990 ADAMS,DOUGLAS,MICHAEL FOUSHEE,J,D SHP (T)SPEEDING 075/55 PLEA: VER: 300592G CLS:3 P: L: JUDGMENT: 6 20IF 702631 ADAMS,KIYOSHI,SHADAZ SANTANA,K DPD (I)FAIL WEAR SEAT BELT-FRONT SEAT PLEA: VER: 344082G JUDGMENT: 7 21IF 700158 ADAMS,MAX,TRAVIS MCINTOSH,C,J SHP (I)FAIL TO WEAR SEAT BELT-DRIVER PLEA: VER: 742243G JUDGMENT: DISTRICT COURT CALENDAR PAGE: 2 COURT DATE: 03/03/21 TIME: 09:00 AM COURTROOM NUMBER: 0002 NO. FILE NUMBER DEFENDANT NAME COMPLAINANT ATTORNEY CONT ************************************************************************************* 8 20CR 703480 ADAMS,MIKE,CAROL COX,A,T SHP 1 (T)SPEEDING 086/65 PLEA: VER: 93582G0 CLS:3