The 9Th Annual Louisiana Studies Conference September 22-23, 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hello. My Name Is Julie Doucet and I'm an Archaeologist with the Louisiana Division of Archaeology. I'm Happy to Participate

Hello. My name is Julie Doucet and I’m an archaeologist with the Louisiana Division of Archaeology. I’m happy to participate in this meeting of the Louisiana Association of Independent Schools, and thanks so much to Cathy Mills for inviting me to join her today. I’d like to share with you the educational resources available from the Louisiana Division of Archaeology to introduce archaeology into the classroom. 1 Why archaeology? Archaeology helps us learn about the past. Archaeology, and its parent field anthropology, are sciences that help us understand ourselves as humans and understand our place in this world. Part of being human is to be curious and inquisitive, which generates many questions. Archaeology is one way to find answers to some of these questions; questions like how did our world or our society get to be this way, and why do certain cultures behave the way they do. How do we learn about the past? Space science has given us a glimpse back in time to the birth of our universe, nearly 8 billion years ago. Geology helps us understand how our planet was formed, going back about 4.5 billion years ago. Paleontology focuses on the origin of life on Earth by studying the fossil remains of plants and animals. History and archaeology also study the past, with more of a focus on the human story. History deals mainly with the written record, while archaeology allows us to go further back in time, before writing. Archaeology helps us understand where, when, how and why people lived. -

Group Tours Please Call and Make Reservations to Ensure Proper Staffing to Accommodate Your Group

Natchitoches Area Convention & Visitors Bureau 780 Front Street, Suite 100 Natchitoches, Louisiana 71457 318-352-8072 | 800-259-1714 www.Natchitoches.com Executive Director: Arlene Gould Group & Tourism Sales: Anne Cummins Military Sites | Natchitoches, LA LUNCH/DINNER | Historic District Dining All historic district restaurants locally owned and operated serving authentic Creole, Cajun and Southern dishes. All restaurants in Louisiana are smoke free. Call for group reservations. For a full listing of restaurants in the historic district please visit Natchitoches.com/dining. EXPLORE | Veteran’s Memorial Park Located to the left of Lasyone’s Meat Pie Kitchen | (318) 357-3106 The Veterans of Foreign Wars Post 1962 and the Natchitoches Parish Veterans and Memorial Park Committee have partnered to develop a site in Historic Downtown Natchitoches to honor our service men and women. This place of honor provides the community not only an area for private reflection but a small gathering place for events honoring the fallen as well. EXPLORE | Fort St. Jean Baptiste State Historic Site 155 rue Jefferson | (318) 357-3101 - Call for Hours & Tour Times Experience the French Colonial life as you are guided through the fort by costumed interpreters. The full sized replica of Fort St. Jean Baptiste, is located on Cane River Lake (formerly the Red River), a few hundred yards from the original fort site, set up by Louis Antoine Juchereau de St. Denis in 1714. Nearly 2,000 treated pine logs form the palisade and approximately 250,000 board feet of treated lumber went into the construction of the buildings. https://www.crt.state.la.us/louisiana-state-parks/historic-sites/fort-st-jean-baptiste-state-historic-site/index DISCOVER | Grand Ecore Visitors Center 106 Tauzin Island Road | (318) 354-8770 - Call for Hours & Tour Times Grand Ecore is also known for the role it played during the Civil War as a Confederate outpost , restructured by the Union Army during the Red River Campaign of 1864, guarding the Red River from Union advancement. -

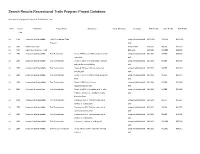

Search Results Recreational Trails Program Project Database

Search Results Recreational Trails Program Project Database Your search for projects in State: LA, Total Results : 421 State Project Trail Name Project Name Description Cong. District(s) County(s) RTP Funds Other Funds Total Funds Year LA 1993 Unspecified/Unidentifiable 1993 Recreational Trails Unspecified/Unidentifi $130,478 $32,620 $163,098 Projects able LA 1997 Kivoli Parish Trail Kivoli Parish $35,000 $8,750 $43,750 LA 1997 USDA Forest Service Trails Statewide $40,000 $10,000 $50,000 LA 2003 Unspecified/Unidentifiable Trail Renovation Create 830 Feet of walking and fitness trail Unspecified/Unidentifi $12,000 $3,000 $15,000 restoration able LA 2003 Unspecified/Unidentifiable Trail Construction Create 1,500 feet of hard surface walking Unspecified/Unidentifi $15,000 $3,000 $18,000 path for fitness and hiking able LA 2003 Unspecified/Unidentifiable Trail Construction Create 4,250 feet of fitness trails in an Unspecified/Unidentifi $10,000 $4,000 $14,000 existing park able LA 2003 Unspecified/Unidentifiable Trail Construction Create 1,275 feet of fitness and interpretive Unspecified/Unidentifi $23,350 $5,863 $29,213 track able LA 2003 Unspecified/Unidentifiable Trail Construction Create 2,500 feet of natural Unspecified/Unidentifi $19,000 $6,000 $25,000 hiking/interpretive trails able LA 2003 Veteran's Memorial Park Trail Construction Create 2,500 feet of walking and exercise Unspecified/Unidentifi $28,000 $7,000 $35,000 Trails to enhance the existing Veterans able Memorial Park LA 2003 Unspecified/Unidentifiable Trail Construction Construct -

Louisiana State Parks Fontainbleau

Louisiana State Parks Fontainbleau Prepared for: Louisiana Department of Culture, Recreation and Tourism The Louisiana Research Team Fontainbleau ECONOMIC ANALYSIS FOUNTAINBLEAU STATE PARK (2004-05) Number of overnight visitors 106,788 Number of day use visitors 106,171 Number of employees - regular 9 Number of employees - peak 20 ECONOMIC IMPACT OF FOUNTAINBLEAU STATE PARK Park visit related spending by out of state visitors in Louisiana businesses $2,055,679 Spending by out of state visitors in park $179,114 Total primary spending by out of state visitors in LA $2,234,793 Secondary economic impact of out of state visitor spending $2,346,533 Total Economic Impact $4,581,326 Earnings for local workers generated by out of state visitors $1,483,903 Jobs generated by out of state visitors 71 LOUISIANA RESIDENT SPENDING Park visit related spending by Louisiana residents in Louisiana businesses $2,003,119 Spending by Louisiana residents in state park $274,340 Total Spending by Louisiana Residents $ 2,277,459 RETURN ON INVESTMENT Direct spending by park visitors (A) $4,512,252 Direct operating expenses (B) $1,140,992 Return on Operating Expenses (A/B) $3.95 1 Fontainbleau The following tables show the overall results of the survey of visitors who stayed overnight at Fontainebleau State Park. Are you a Louisiana resident? Table 1 Response Percentage Yes 60.5% No 39.5% Total 100.0% Was this your first visit to this park? Table 2 Response Percentage Yes 31.0% No 69.0% Total 100.0% 2 Fontainbleau How many nights did you and your party spend at this Louisiana state park? Table 3 Response Percentage 0 nights 1.8% 1-3 nights 71.9% 4-9 nights 21.9% 10+ nights 4.5% Total 100.0% What did you like best about this state park? Table 4 Response Percentage Clean/Good Facilities 16.5% Relaxing Atmosphere 23.9% Nature/Outdoor environment 40.4% Accessibility 13.8% Other 5.5% Total 100.0% 3 Fontainbleau What did you like least about this state park? Table 5 Response Percentage Nothing to dislike 37.3% Mosquitoes, flies, ants, bees etc. -

Unit 3: Exploration and Early Colonization (Part 2)

Unit 3: Exploration and Early Colonization (Part 2) Spanish Colonial Era 1700-1821 For these notes – you write the slides with the red titles!!! Goals of the Spanish Mission System To control the borderlands Mission System Goal Goal Goal Represent Convert American Protect Borders Spanish govern- Indians there to ment there Catholicism Four types of Spanish settlements missions, presidios, towns, ranchos Spanish Settlement Four Major Types of Spanish Settlement: 1. Missions – Religious communities 2. Presidios – Military bases 3. Towns – Small villages with farmers and merchants 4. Ranchos - Ranches Mission System • Missions - Spain’s primary method of colonizing, were expected to be self-supporting. • The first missions were established in the El Paso area, then East Texas and finally in the San Antonio area. • Missions were used to convert the American Indians to the Catholic faith and make loyal subjects to Spain. Missions Missions Mission System • Presidios - To protect the missions, presidios were established. • A presidio is a military base. Soldiers in these bases were generally responsible for protecting several missions. Mission System • Towns – towns and settlements were built near the missions and colonists were brought in for colonies to grow and survive. • The first group of colonists to establish a community was the Canary Islanders in San Antonio (1730). Mission System • Ranches – ranching was more conducive to where missions and settlements were thriving (San Antonio). • Cattle were easier to raise and protect as compared to farming. Pueblo Revolt • In the late 1600’s, the Spanish began building missions just south of the Rio Grande. • They also built missions among the Pueblo Indians of New Mexico. -

Louisiana State Parks Facilities and Activities

Louisiana State Parks' and Historic Sites' Trails Please contact the park for specific information about their trails, or visit their webpage. Total Total ADA Trail ADA Trail Accessible Hiking Biking Canoeing Equestrian Length Accessible Hiking Biking Canoeing Equestrian Length State Parks State Historic Sites Audubon; phone: (888)677-2838 0.4 mile 2.8 Bayou Segnette; phone: (888)677-2296 miles 0.25 Centenary; phone: (888)677-2364 mile Bogue Chitto; phone: (888)677-7312 21 miles Fort Jesup; phone: (888)677-5378 9.35 Chemin-A-Haut; phone: (888)677-2436 miles Fort Pike; phone: (888)662-5703 35.8 Chicot; phone: (888)677-2442 Fort St. Jean Baptiste; phone: (888)677-7853 miles Forts Randolph & Buhlow; phone: (888)677- .75 mile Cypremort Point; phone: (888)867-4510 7437 0.25 Fairview-Riverside; phone: (888)677-3247 Locust Grove; phone: (888)677-2838 mile Longfellow-Evangeline; phone: (888)677-2900 1 mile 5.75 Fontainebleau; phone: (888)677-3668 miles Los Adaes; phone: (318)472-9449 2 miles Grand Isle; phone: (888)787-2559 2 miles Mansfield; phone: (888)677-6267 1 mile Hodges Gardens; phone: (800)354-3523 10 miles Marksville; phone: (888)253-8954 0.5 mile Jimmie Davis; phone: (888)677-2263 0.5 mile Plaquemine Lock; phone: (877)987-7158 1 mile 25.5 Lake Bistineau; phone: (888)677-2478 Port Hudson; phone: (888)677-3400 6 miles miles 2.6 Lake Bruin; phone: (888)677-2784 Poverty Point; phone: (888)926-5492 miles 12.3 Lake Claiborne; phone: (888)677-2524 miles Rebel; phone: (888)677-3600 0.5 mile Lake D'Arbonne; phone: (888)677-5200 7 miles Rosedown Plantation; phone: (888)376-1867 5.4 Winter Quarters; phone: (888)677-9468 Lake Fausse Pointe; phone: (888)677-7200 miles 5.5 Total North Toledo Bend; phone: (888)677-6400 miles ADA Trail Accessible Hiking Biking Canoeing Equestrian Length 0.7 Palmetto Island; phone: (877)677-0094 miles State Preservation Area Poverty Point Reservoir; phone: (800)474- 2.5 0392 miles 2.9 LA State Arboretum; phone: (888)677-6100 miles St. -

Appendix G: Recreational Resources

APPENDIX G: RECREATIONAL RESOURCES ID PARK NAME LOCATION RECREATIONAL ACTIVITIES 1 Beaver Lake State Park Rogers, Arkansas Walking, fishing, picnicking 2 Bull Shoals State Park Bull Shoals, Arkansas Walking, fishing, picnicking 3 Devil’s Den State Park West Fork, Arkansas Walking, fishing swimming, picnicking, jogging, biking 4 Lake Fort Smith State Park Mountainburg, Arkansas Walking, fishing, swimming, picnicking, jogging 5 Mammoth Spring State Park Mammoth Spring, Arkansas Walking, fishing, picnicking 6 Withrow Springs State Park Huntsville, Arkansas Walking, fishing, swimming, picnicking, jogging, baseball/softball 7 Lake Poinsett State Park Harrisburg, Arkansas Walking, fishing, driving, picnicking, jogging, biking 8 Louisiana Purchase State Park Near Brinkley, Arkansas Walking 9 Old Davidsonville State Park Pocahontas, Arkansas Walking, fishing, driving, picnicking, jogging, biking 11 Village Creek State Park Wynne, Arkansas Walking, fishing, driving, picnicking, jogging, biking 12 Crowley’s Ridge State Park Walcott, Arkansas Walking, fishing, driving, swimming, picnicking, jogging, biking 13 Jacksonport State Park Jacksonport, Arkansas Walking, fishing, driving, swimming, picnicking, jogging, biking 14 Lake Charles State Park Powhatan, Arkansas Walking, fishing, driving, swimming, picnicking, jogging, biking 15 Lake Chicot State Park Lake Village, Arkansas Walking, fishing, driving, swimming, picnicking, jogging, biking 16 Lake Frierson State Park Jonesboro, Arkansas Walking, fishing, driving, picnicking, jogging, biking 17 Pinnacle -

Beauregard Airport Industrial Site Phase I Cultural Resources

RR Exhibit EE. Beauregard Airport Industrial Site Phase I Cultural Resources Assessment Report PHASEICULTURALRESOURCESSURVEYOF 1,170 ACRES (473.5 HECTARES) NEAR DERIDDER,BEAUREGARDPARISH,LOUISIANA DRAFT REPORT For SWLA Economic Development Alliance 4310 Ryan St. Lake Charles, LA 70602 September 27, 2016 1 PHASEICULTURALRESOURCESSURVEYOF 1,170 ACRES (473.5 HECTARES) NEAR DERIDDER,BEAUREGARDPARISH,LOUISIANA Draft Report By Matthew Chouest, Brandy Kerr, and Malcolm Shuman For SWLA Economic Development Alliance 4310 Ryan St. Lake Charles, LA 70602 Surveys Unlimited Research Associates, Inc. P.O. Box 14414 Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70898-4414 September 27, 2016 2 ABSTRACT From July 6, 2016, to August 28, 2016, Surveys Unlimited Research Associates, Inc. (SURA, Inc.) conducted a Phase I cultural resource survey of 1,170 acres (ac) (473.5 hectares [ha]) west of Beauregard Regional Airport located in DeRidder, Beauregard Parish, Louisiana. A total of 6,335 shovel tests were excavated. Four archaeological sites were discovered—BPASA-1 (16BE104), BPASA-2 (16BE105), BPASA-3 (16BE106), and BPASA-4 (16BE107). The authors suggest that because of the disturbance due to modern hunting activities and pine cultivation, these sites do not possess the qualities of significance and are not eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places under Criterion D. Four isolated finds were also noted. None of these finds contain sufficient artifacts, or secure enough proveniences to be considered for the NRHP. As a result, no further work is recommended for the surveyed area. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The field crew was led by Mr. Matthew Chouest, M.A., and consisted of Ms. Rivers Berryhill, Mr. Jason Foust, Ms. -

Poverty Point

Louisiana State Parks Poverty Point Prepared for: Louisiana Department of Culture, Recreation and Tourism The Louisiana Research Team Poverty Point ECONOMIC ANALYSIS POVERTY POINT STATE PARK (2004-05) Number of overnight visitors 7,714 Number of day use visitors 26,740 Number of employees - regular 8 Number of employees - peak 18 ECONOMIC IMPACT OF POVERTY POINT STATE PARK Park visit related spending by out of state visitors in Louisiana businesses $67,513 Spending by out of state visitors in park $28,058 Total primary spending by out of state visitors in LA $95,570 Secondary economic impact of out of state visitor spending $100,349 Total Economic Impact $195,919 Earnings for local workers generated by out of state visitors $63,459 Jobs generated by out of state visitors 3 LOUISIANA RESIDENT SPENDING Park visit related spending by Louisiana residents in Louisiana businesses $151,117 Spending by Louisiana residents in state park $87,406 Total Spending by Louisiana Residents $238,523 RETURN ON INVESTMENT Direct spending by park visitors (A) $334,093 Direct operating expenses (B) $536,109 Return on Operating Expenses (A/B) $0.62 1 Poverty Point The following tables show the overall results of the survey of visitors who stayed overnight at Poverty Point State Park. Are you a Louisiana resident? Table 1 Response Percentage Yes 75.7% No 24.3% Total 100.0% Was this your first visit to this park? Table 2 Response Percentage Yes 27.1% No 72.9% Total 100.0% 2 Poverty Point How many nights did you and your party spend at this Louisiana state park? Table 3 Response Percentage 0 nights 0.0% 1-3 nights 74.9% 4-9 nights 19.5% 10+ nights 5.6% Total 100.0% What did you like best about this state park? Table 4 Response Percentage Clean/Good Facilities 35.6% Relaxing Atmosphere 21.9% Nature/Outdoor environment 32.9% Accessibility 2.7% Other 6.8% Total 100.0% 3 Poverty Point What did you like least about this state park? Table 5 Response Percentage Nothing to dislike 58.6% Mosquitoes, flies, ants, bees etc. -

Cane River Lake, Louisiana

·-: .· .. ·_ o-~tC1") . SpeciaL.~source- Study. Environmental Ass.essment L: 0 (J l S. I .A N A ·tPANE RIVER ·· · · . Louisiana . HL'.SE. RETURN TO:. TECHmCJ\L n:r::::.~.m:N c:::nrn B&WScans C::rJVER SEiWiCE c::ViiEil ON MICROFILM ~i .. lL.{. _Z6C> ~- . fMTIO~Al PARK SERVICE . .· @.Print~d· on Recycled Paper Special Resource Study Environmental Assessment June 1993 Cane River Lake, Louisiana CANE RIVER Louisiana United States Department of the Interior • National Park Service • Denver Service Center SUMMARY As directed by Congress, the National Park Service has initiated a special resource study to identify and evaluate alternatives for managing, preserving, and interpreting historic structures, sites, and landscapes within the Cane River area of northwestern Louisiana, and how Creole culture developed in this area. The study includes an evaluation of resources for possible inclusion in the national park system using the requirements set forth in the NPS publication Criteria for Parklands, including criteria for national significance, suitability, and feasibility. The study area boundary includes Natchitoches Parish (pronounced Nack-a-tish), which still retains significant aspects of Creole culture. White Creoles of colonial Louisiana were born of French or Spanish parents before 1803. The tangible close of this period came with the formal establishment of United States presence as represented by Fort Jesup. Creoles of color emerged from freed slaves who owned plantations, developed their own culture, and enjoyed the respect and friendship of the dominant white Creole society. In Louisiana, Creole could refer to those of European, Afro-European heritage, or European-Indian heritage. The study area also includes Cane River Lake (originally the main channel for the Red River) and 4 miles of the Cane River to Cloutierville. -

French Influences at Los Adaes by George Avery

French Influences at Los Adaes by George Avery Introduction Phillip V was placed on the Spanish throne. A presidio (or fort) and mission were The War of Spanish Succession (1701-1714) established by the Spanish in 1721 near was fought to defend the choice of the what is now Robeline, Louisiana, in reaction Bourbons occupying the throne of Spain, to the French attack on the Spanish mission and the French fought with the Spanish for the Adaes Indians in 1719. The presidio against the Holy Roman Empire, the British, was called Nuestra Señora del Pilar de los the Dutch, and Portugal. The French and Adaes, and the mission was called Mision Spanish prevailed, and even though the San Miguel de Cuellar de los Adaes, named Bourbons were French, this did not prevent after the Adaes Indians in the area. The fort Phillip V from waging war on the French and mission—collectively referred to as Los and others some years later in the War of the Adaes—were occupied until 1773. Even Quadruple Alliance (1718-1720). though the establishment of Los Adaes in The French attack on Mision San 1721 was a reaction to French military Miguel de los Adaes in 1719 was part of the aggression, the years that followed were War of the Quadruple Alliance and has been characterized more by accommodation and referred to as the Chicken War because it mutual support than by conflict. The French was the Spanish chickens that fought most influences at Los Adaes from 1721 to 1773 valiantly against the French intruders from will be discussed drawing on both historical Natchitoches. -

Natchitoches Parish Bexar County

National Register of Historic Places/National Historic Landmarks Associated with the El Camino Real de los Tejas LOUISIANA Natchitoches Parish Name: Los Adaes State Historic Site Historic use type: Mission and presidio site Description: El Presidio de Nuestra Señora del Pilar de Zaragoza de los Adaes served as the capital of the province of Tejas from 1728 to 1773, when Spanish authorities decided to close it. Archeological excavations have found the remains of both the mission and presidio. The site is a National Historic Landmark. Time period: 1717–1773 Ownership: Public (Louisiana Office of State Parks) TEXAS Bexar County Name: Iglesia de Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria y Guadalupe/San Fernando Cathedral Historic use type: Church Description: Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, this was the parish church of the villa of San Fernando de Bexar, which was built between 1737 and 1749 and restored in 1839. The gothic Cathedral of San Fernando, built between 1868 and 1873, incorporated portions of the existing Spanish church. Time period: 1737–present Ownership: Archdiocese of San Antonio Name: Mission Espada Aqueduct Historic use type: Irrigation feature Description: Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, this aqueduct is an important structure associated with Mission Espada. Time period: 1700s Ownership: Public (National Park Service) Name: Mission Espada Dam Historic use type: San Antonio River crossing/Irrigation feature Description: Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, this dam is a Spanish Colonial irrigation feature, which served as a river crossing, connecting the local network of roads between missions on both banks of the San Antonio River.