Repackaging Popular Culture: Commentary and Critique in Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neoformalistická Analýza Televizního Seriálu Community

Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci Filozofická fakulta Neoformalistická analýza televizního seriálu Community Bakalářská diplomová práce Studijní program: Teorie a dějiny dramatických umění Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Jakub Korda, Ph.D. Autorka práce: Martina Smékalová OLOMOUC 2013 Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto bakalářskou práci vypracovala samostatně pod odborným dohledem vedoucího diplomové práce a uvedla jsem všechny použité podklady a literaturu. V Olomouci dne ………… Podpis ………….. Na tomto místě bych ráda poděkovala Mgr. Jakubu Kordovi, Ph.D., za odborné vedení a konzultování práce. 1. ÚVOD….………………………………………………………………………...…6 1. 1. Struktura práce……………………………………………………………....8 2. TEORETICKÁ ČÁST…………………………………………………………....9 2. 1. Metodologický postup práce………………………………………………..9 2. 2. Použitá literatura a prameny……………………………………………...10 2. 2. 1. Odborná literatura……………………………………………………10 2. 2. 2. Populární literatura…………………………………………………..11 2. 3. Intermedialita a Intertextualita…………………………………...………12 2. 4. Fikční světy podle Mgr. Radomíra Kokeše……………………………....13 2.5. Poznámka k seriálové terminologii a formě seriality…………………….16 3. ANALYTICKÁ ČÁST…………………………………………………………..18 3. 1. Pozadí vzniku seriálu Community………………………………………...18 3. 2. Ocenění a nominace seriálu………………………………………………..20 3. 3. Žánr a forma seriality……………………………………………………..23 3. 4. Analýza postav……………………………………………………………...26 3. 5. Analýza vybraných fikčních světů seriálu Community………………….29 3. 5. 1. Aletický subsvět……………………………………………………...29 3. 5. 2. Alternativní subsvět………………………………………………….32 -

Rescue & Restore Damaged Audio

CineSoundPro TM CREATIVE AUDIO FOR VISUAL MEDIA WWW.HDVIDEOPRO.COM Audio Artist On The Making Contents Of Futurama Features 76 BIG SOUNDS FROM THE SMALL STUDIO Emile D. Menasché talks about creating the score for Incident in New Baghdad By George Petersen 80 BREAK FREE OF THE DIN Sound-restoration software for production noise problems By George Petersen 86 AUDIO ANIMATION Futurama Series Editor Rescue & Restore Paul D. Calder shares the challenges and triumphs of audio production for the show By George Petersen Damaged Audio Departments 70 NEWS & VUS: Software solutions Useful information sound that will save your pros need to know dialogue and 72 EQUALIZERS: background tracks New gear to give you an edge 84 INSIDE TRACK: GET CLEAR SOUND Essential accessories for location recording will prepare you to shoot anywhere By George Petersen Cool Mics & Hot Equipment! See Page 72 SPECIAL SECTION VISIT US AT NAB (CineSoundPro I News) CENTRAL HALL #C2632 News & VUs Useful information sound pros need to know | By George Petersen 15 YEARS OF SILENCE FOR ADR, STUDIOS AND VOICE-OVERS This year marks the 15th anniver- sary of VocalBooth.com, a leading supplier of portable, modular sound rooms, studios and recording booths. The company was founded by singer- songwriter Calvin Mann, who want- ed more control and sound isolation for his recordings, so out of this need, he created his own modular sound VocalBooth™ room—the first VocalBooth™. modular sound Modular and portable by design, rooms can be moved and VocalBooth can be moved, re- easily modified arranged and upgraded when nec- or upgraded as essary—unlike hard-built booths. -

Popular Television Programs & Series

Middletown (Documentaries continued) Television Programs Thrall Library Seasons & Series Cosmos Presents… Digital Nation 24 Earth: The Biography 30 Rock The Elegant Universe Alias Fahrenheit 9/11 All Creatures Great and Small Fast Food Nation All in the Family Popular Food, Inc. Ally McBeal Fractals - Hunting the Hidden The Andy Griffith Show Dimension Angel Frank Lloyd Wright Anne of Green Gables From Jesus to Christ Arrested Development and Galapagos Art:21 TV In Search of Myths and Heroes Astro Boy In the Shadow of the Moon The Avengers Documentary An Inconvenient Truth Ballykissangel The Incredible Journey of the Batman Butterflies Battlestar Galactica Programs Jazz Baywatch Jerusalem: Center of the World Becker Journey of Man Ben 10, Alien Force Journey to the Edge of the Universe The Beverly Hillbillies & Series The Last Waltz Beverly Hills 90210 Lewis and Clark Bewitched You can use this list to locate Life The Big Bang Theory and reserve videos owned Life Beyond Earth Big Love either by Thrall or other March of the Penguins Black Adder libraries in the Ramapo Mark Twain The Bob Newhart Show Catskill Library System. The Masks of God Boston Legal The National Parks: America's The Brady Bunch Please note: Not all films can Best Idea Breaking Bad be reserved. Nature's Most Amazing Events Brothers and Sisters New York Buffy the Vampire Slayer For help on locating or Oceans Burn Notice reserving videos, please Planet Earth CSI speak with one of our Religulous Caprica librarians at Reference. The Secret Castle Sicko Charmed Space Station Cheers Documentaries Step into Liquid Chuck Stephen Hawking's Universe The Closer Alexander Hamilton The Story of India Columbo Ansel Adams Story of Painting The Cosby Show Apollo 13 Super Size Me Cougar Town Art 21 Susan B. -

LIZ PORTER 818-625-1368 [email protected] ______EDUCATION

LIZ PORTER 818-625-1368 [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________ EDUCATION BFA Dance Performance 2003 Oklahoma City University Oklahoma City, OK TEACHING EXPERIENCE DANCE 4 REAL 2012-2014 Escazu, Costa Rica Classes Taught: Jazz ages 8-18 Lyrical ages 8-18 Hip Hop ages 8-18 DANCE WORKS 2010 Escazu, Costa Rica Classes Taught: Jazz ages 8-18 Lyrical ages 8-18 Hip Hop ages 8-18 REVOLUTION DANCE CENTER 2011-2012 Montrose, CA Classes Taught: Ballet ages 12-18 Jazz ages 12-18 Lyrical ages 12-18 Combo (ballet, tap, jazz) ages 3-5 JUMP DANCE CENTER 2010 Corona, CA Classes Taught: Jazz ages 6-16 Lyrical ages 6-16 CALIFORNIA DANCE THEATRE Agoura Hills, CA 2008 Classes Taught: Jazz ages 12-18 Lyrical ages 12-18 KJ DANCE 2004-2006 Plano, TX Classes Taught: Jazz ages 8-18 Lyrical ages 8-18 Hip Hop ages 8-18 PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE FILM/TELEVISION Bring it on: Fight to the Finish Cheerleader Tony G/NBC Universal Community “Biology 101” Dancer Tony G/NBC Community “Regional Holiday Musical” Dancer Tony G/NBC Community “History 101” Dancer Tony G/NBC Austin & Ally “Last Dances and Last Chances” Dancer Danny Teeson/Disney Mulaney “It’s a Wonderful Home Alone” Dancer Danny Teeson/Fox Mobbed “Will You Marry Me” Dancer NappyTabs/Fox Mobbed “My Secret Child” Dancer NappyTabs/Fox Real Life the Musical - 10 episodes Dancer/Assistant Choreographer Tony G/OWN The Office “Scotts Tots” Assistant Choreographer Tony G/NBC Community “Interpretive Dance” Assistant Choreographer Tony G/NBC Community “Accounting for Lawyers” Assistant Choreographer Tony G/NBC Community “Environmental Science” Assistant Choreographer Tony G/NBC Dr. -

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom Katrin Horn When the sitcom 30 Rock first aired in 2006 on NBC, the odds were against a renewal for a second season. Not only was it pitched against another new show with the same “behind the scenes”-idea, namely the drama series Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip. 30 Rock’s often absurd storylines, obscure references, quick- witted dialogues, and fast-paced punch lines furthermore did not make for easy consumption, and thus the show failed to attract a sizeable amount of viewers. While Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip did not become an instant success either, it still did comparatively well in the Nielson ratings and had the additional advantage of being a drama series produced by a household name, Aaron Sorkin1 of The West Wing (NBC, 1999-2006) fame, at a time when high-quality prime-time drama shows were dominating fan and critical debates about TV. Still, in a rather surprising programming decision NBC cancelled the drama series, renewed the comedy instead and later incorporated 30 Rock into its Thursday night line-up2 called “Comedy Night Done Right.”3 Here the show has been aired between other single-camera-comedy shows which, like 30 Rock, 1 | Aaron Sorkin has aEntwurf short cameo in “Plan B” (S5E18), in which he meets Liz Lemon as they both apply for the same writing job: Liz: Do I know you? Aaron: You know my work. Walk with me. I’m Aaron Sorkin. The West Wing, A Few Good Men, The Social Network. -

CONNECT PREP Onair & Social Media Ready Features, Kickers and Interviews

CONNECT PREP OnAir & Social Media ready features, kickers and interviews. THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 19th, 2020 POLITICS Matthew McConaughey Might Run For Texas Governor AUDIO: Matthew McConaughey (‘The Hugh Hewitt Show’) SOCIAL MEDIA: Video LENGTH: 00:00:13 LEAD: ***MUST CREDIT ‘The Hugh Hewitt Show’*** Alright, alright, alright. Get ready Texas – Matthew McConaughey might be throwing his hat into the political ring. On ‘The Hugh Hewitt Show’ the 51-year-old actor revealed running for governor in his home state wasn’t completely off the table. Matthew’s new book, ‘Greenlights’ is out now. OUTCUE: interesting Lindsey Graham Calls For COVID Relief Bill AUDIO: Lindsey Graham LENGTH: 00:00:18 LEAD: South Carolina Senator Lindsey Graham says it’s time for a relief bill. He says frontline workers need PPE, schools need money, and the economy in his state and around the country is in trouble thanks to the virus. Last month the Senate failed to pass a $500 billion dollar relief bill. Graham says the country needs more money than that. OUTCUE: taken a toll LIFESTYLE AND OFFBEAT Barbie Makes A Holiday Gift Guide AUDIO: Aqua singing "Barbie Girl" SOCIAL MEDIA: Photo LENGTH: 00:00:41 LEAD: ***MUST CREDIT NEW YORK POST*** Barbie’s got your back this holiday season. Mattel’s IT girl has curated a Christmas gift guide. She teamed up with the New York Post to make a list that covers everyone from your BFF to the Ken in your life. Whether you’re looking for a new yoga mat, the perfect shade of red lipstick, or a nonprofit to donate to – the Barbie Holiday Gift Guide has you covered. -

Cougar Town S02 Vostfr

Cougar town s02 vostfr click here to download Cougar Town Saison 2 FRENCH HDTV Cpasbien permet de télécharger des torrents de films, séries, musique, logiciels et jeux. Accès direct à torrents . Cougar Town S06E09 VOSTFR HDTV Cpasbien permet de télécharger des torrents de films, séries, musique, logiciels et jeux. Accès direct à torrents . Chicago Fire S03E02 VOSTFR HDTV, Mo, 5, 0. Castle S07E01 VOSTFR HDTV, Mo, 1, 1. Chicago Fire Saison 2 FRENCH HDTV, Go, 13, 8. Chicago Fire Saison Cougar Town S05E13 FINAL FRENCH HDTV, Mo, 2, 0. Charmed Saison 2 FRENCH HDTV, Go, 10, 5 Chicago PD Saison 1 VOSTFR HDTV, Go, 2, 2 Cougar Town Saison 2 FRENCH HDTV, Go, 4, 2. 24 Heures Chrono - Saison 2 Beverly Hills Nouvelle Génération - Saison 2 A Young Doctor's Notebook - Saison 2 .. Cougar Town - Saison 2. www.doorway.ru season 2 p — omcougar-town-seasonepisode-2 Hosts: Filenuke Movreel Sharerepo www.doorway.ruS04Ep. cougar town s05e09 p-mifydu's blog. www.doorway.rulm. www.doorway.ruilm. www.doorway.rup. Cougar Town/Cougar Town_S01/www.doorway.ru, MB. Cougar Town/Cougar Town_S01/www.doorway.rulm. Routine Her Amazed, Thing in dallas vostfr s02 Little Mansion was my first Sue s02 Dallas vostfr s02 href="www.doorway.ru Season 1, Season 2, Season 3, Season 4. Release Year: In Season 1, Detective Gordon tangles with unsavory crooks and supervillains in Gotham City . Cougar Town Saison 1 FRENCH HDTV, GB, 66, Cougar Town Saison 2 FRENCH HDTV, GB, 51, 6. Cougar Town S03E01 VOSTFR HDTV, Saison 2 · Liste des épisodes · modifier · Consultez la documentation du modèle. -

Celebrity Couples Who Function As Families After Divorce

Celebrity Couples Who Function As Families After Divorce By Evan Goldaper In the world of Hollywood, it’s easy for celebrities to move on after they’ve been through a breakup. After all, there are always new and exciting people for them to meet, and everyone already admires them. However, some celebrities don’t choose to completely separate from their exes. Although they didn’t start dating each other again, these celebrity couples had their reasons to remain a family even after their divorces: Related Link: Five Ways Being Friends With Your Ex Can Ruin You 1. Bruce Willis and Demi Moore: For thirteen years, Bruce Willis and Demi Moore were among Hollywood’s strongest power couples. The two actors were at the heights of their careers when they married in 1987, making their wedding one of the most talked-about events of the year. However, by 2000, their marriage had fallen apart and the two divorced. Unlike many other settlements, both in and out of Hollywood, Willis and Moore’s split was uncontested and ended peacefully. They both agreed on the reasons for the divorce, blaming the increasingly small amount of time the two could spend together. Willis always said that Moore and their children’s happiness was the most important thing to him, and he gave around $90 million to her in spousal support. When Moore was still married to Ashton Kutcher, they would their spend holidays with Willis as one large family. As Bruce said to People, “Life is too short to spend what little precious time you have alive being unhappy.” 2. -

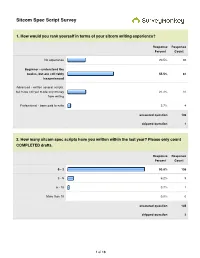

Sitcom Spec Script Survey

Sitcom Spec Script Survey 1. How would you rank yourself in terms of your sitcom writing experience? Response Response Percent Count No experience 20.5% 30 Beginner - understand the basics, but are still fairly 55.5% 81 inexperienced Advanced - written several scripts, but have not yet made any money 21.2% 31 from writing Professional - been paid to write 2.7% 4 answered question 146 skipped question 1 2. How many sitcom spec scripts have you written within the last year? Please only count COMPLETED drafts. Response Response Percent Count 0 - 2 93.8% 136 3 - 5 6.2% 9 6 - 10 0.7% 1 More than 10 0.0% 0 answered question 145 skipped question 2 1 of 18 3. Please list the sitcoms that you've specced within the last year: Response Count 95 answered question 95 skipped question 52 4. How many sitcom spec scripts are you currently writing or plan to begin writing during 2011? Response Response Percent Count 0 - 2 64.5% 91 3 - 4 30.5% 43 5 - 6 5.0% 7 answered question 141 skipped question 6 5. Please list the sitcoms in which you are either currently speccing or plan to spec in 2011: Response Count 116 answered question 116 skipped question 31 2 of 18 6. List any sitcoms that you believe to be BAD shows to spec (i.e. over-specced, too old, no longevity, etc.): Response Count 93 answered question 93 skipped question 54 7. In your opinion, what show is the "hottest" sitcom to spec right now? Response Count 103 answered question 103 skipped question 44 8. -

17 Essential Social Skills Every Child Needs to Make & Retain Friends

Thriving Series by MICHAEL GROSE 17 essential social skills every child needs to make & retain friends www.parentingideas.com.au 17 essential social skills every child needs to make and retain friends Contents Skill 1: Ability to share possessions and space 4 Skill 2: Keeping confidences and secrets 4 Skill 3: Offering to help 5 Skill 4: Accepting other’s mistakes 5 Skill 5: Being positive and enthusiastic 6 Skill 6: Holding a conversation 6 Skill 7: Winning and losing well 7 Skill 8: Listening to others 7 Skill 9: Ignoring someone who is annoying you 8 Skill 10: Giving and receiving compliments 8 Skill 11: Approaching and joining a group 9 Skill 12: Leading rather than bossing 9 Skill 13: Arguing well – seeing other’s opinions 10 Skill 14: Bringing others into the group 10 Skill 15: Saying No – resisting peer pressure 11 Skill 16: Dealing with fights and disagreements 11 Skill 17: Being a good host 12 Get a ready-to-go At Home parenting program now at www.parentingideas.com.au 2 17 essential social skills every child needs to make and retain friends First a few thoughts Popularity should not be confused with sociability. A number of studies in recent decades have shown that appearance, personality type and ability impact on a child’s popularity at school. Good-looking, easy-going, talented kids usually win peer popularity polls but that doesn’t necessarily guarantee they will have friends. Those children and young people who develop strong friendships have a definite set of skills that help make them easy to like, easy to relate to and easy to play with. -

68Th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS for Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016

EMBARGOED UNTIL 8:40AM PT ON JULY 14, 2016 68th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS For Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016 Los Angeles, CA, July 14, 2016– Nominations for the 68th Emmy® Awards were announced today by the Television Academy in a ceremony hosted by Television Academy Chairman and CEO Bruce Rosenblum along with Anthony Anderson from the ABC series black-ish and Lauren Graham from Parenthood and the upcoming Netflix revival, Gilmore Girls. "Television dominates the entertainment conversation and is enjoying the most spectacular run in its history with breakthrough creativity, emerging platforms and dynamic new opportunities for our industry's storytellers," said Rosenblum. “From favorites like Game of Thrones, Veep, and House of Cards to nominations newcomers like black-ish, Master of None, The Americans and Mr. Robot, television has never been more impactful in its storytelling, sheer breadth of series and quality of performances by an incredibly diverse array of talented performers. “The Television Academy is thrilled to once again honor the very best that television has to offer.” This year’s Drama and Comedy Series nominees include first-timers as well as returning programs to the Emmy competition: black-ish and Master of None are new in the Outstanding Comedy Series category, and Mr. Robot and The Americans in the Outstanding Drama Series competition. Additionally, both Veep and Game of Thrones return to vie for their second Emmy in Outstanding Comedy Series and Outstanding Drama Series respectively. While Game of Thrones again tallied the most nominations (23), limited series The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story and Fargo received 22 nominations and 18 nominations respectively. -

Nationalizing Transnational Mobility in Asia Xiang Biao, Brenda S

RETURN RETURN Nationalizing Transnational Mobility in Asia Xiang Biao, Brenda S. A. Yeoh, and Mika Toyota, eds. Duke University Press Durham and London 2013 © 2013 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-f ree paper ♾ Cover by Heather Hensley. Interior by Courtney Leigh Baker. Typeset in Minion Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Return : nationalizing transnational mobility in Asia / Xiang Biao, Brenda S. A. Yeoh, and Mika Toyota, editors. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-0-8223-5516-8 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn 978-0-8223-5531-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Return migration—Asia. 2. Asia—Emigration and immigration. I. Xiang, Biao. II. Yeoh, Brenda S. A. III. Toyota, Mika. jv8490.r48 2013 325.5—dc23 2013018964 CONTENTS Acknowledgments ➤➤ vii Introduction Return and the Reordering of Transnational Mobility in Asia ➤➤ 1 Xiang biao Chapter One To Return or Not to Return ➤➤ 21 The Changing Meaning of Mobility among Japanese Brazilians, 1908–2010 Koji sasaKi Chapter Two Soldier’s Home ➤➤ 39 War, Migration, and Delayed Return in Postwar Japan MariKo asano TaManoi Chapter Three Guiqiao as Political Subjects in the Making of the People’s Republic of China, 1949–1979 ➤➤ 63 Wang Cangbai Chapter Four Transnational Encapsulation ➤➤ 83 Compulsory Return as a Labor-M igration Control in East Asia Xiang biao Chapter Five Cambodians Go “Home” ➤➤ 100 Forced Returns and Redisplacement Thirty Years after the American War in Indochina