Parroccini Kimberleigh2019.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FALL 2013.Indd

The Print Club of New York Inc Fall 2013 reminder to those of you who still have to send in your President’s Greeting dues. We will move to the waiting list in mid October, Mona Rubin and we don’t want to lose any of you. We will keep you updated about the shipping of the he fall is always an exciting time for print fans as prints. Our goal is to get the first batch out by early we gear up for a new season. November and a second batch in the spring. Therefore Once again we will be receiving our VIP passes it is best to rejoin now and make it onto the initial ship- T ping list. for the IFPDA Print Fair in November, and we have already been invited as guests to the breakfast hosted by As always, we welcome your input about ideas for International Print Center New York on November 9th. events, and please let us know if you would like to join Watch for details about these great membership benefits any committees. That is always the best way to get the and hope there won’t be any big storms this year. most out of the Club. Be sure to mark your calendars for October 21st. Kay In a few days, my husband and I are heading off to Deaux has arranged a remarkably interesting event at a Amsterdam, home to some of the greatest artists of all relatively new studio that combines digital printing with time. We will be staying in an apartment in the neighbor- traditional techniques. -

The Angel of Ferrara

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Goldsmiths Research Online The Angel of Ferrara Benjamin Woolley Goldsmith’s College, University of London Submitted for the degree of PhD I declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own Benjamin Woolley Date: 1st October, 2014 Abstract This thesis comprises two parts: an extract of The Angel of Ferrara, a historical novel, and a critical component entitled What is history doing in Fiction? The novel is set in Ferrara in February, 1579, an Italian city at the height of its powers but deep in debt. Amid the aristocratic pomp and popular festivities surrounding the duke’s wedding to his third wife, the secret child of the city’s most celebrated singer goes missing. A street-smart debt collector and lovelorn bureaucrat are drawn into her increasingly desperate attempts to find her son, their efforts uncovering the brutal instruments of ostentation and domination that gave rise to what we now know as the Renaissance. In the critical component, I draw on the experience of writing The Angel of Ferrara and nonfiction works to explore the relationship between history and fiction. Beginning with a survey of the development of historical fiction since the inception of the genre’s modern form with the Walter Scott’s Waverley, I analyse the various paratextual interventions—prefaces, authors’ notes, acknowledgements—authors have used to explore and explain the use of factual research in their works. I draw on this to reflect in more detail at how research shaped the writing of the Angel of Ferrara and other recent historical novels, in particular Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall. -

* Diploma Lecture Series 2012 Absolutism to Enlightenment

Diploma Lecture Series 2012 Absolutism to enlightenment: European art and culture 1665-1765 Jan van Huysum: the rise and strange demise of the baroque flower piece Richard Beresford 21 / 22 March 2012 Introduction: At his death in 1749 Jan van Huysum was celebrated as the greatest of all flower painters. His biographer Jan van Gool stated that Van Huysum had ‘soared beyond all his predecessors and out of sight’. The pastellist Jean-Etienne Liotard regarded him as having perfected the oil painter’s art. Such was contemporary appreciation of his works that it is thought he was the best paid of any painter in Europe in the 18th century. Van Huysum’s reputation, however, was soon to decline. The Van Eyckian perfection of his technique would be dismissed by a generation learning to appreciate the aesthetic of impressionism. His artistic standing was then blighted by the onset of modernist taste. The 1920s and 30s saw his works removed from public display in public galleries, including both the Rijksmuseum and the Mauritshuis. The critic Just Havelaar was not the only one who wanted to ‘sweep all that flowery rubbish into the garbage’. Echoes of the same sentiment survive even today. It was not until 2006 that the artist received his first serious re-evaluation in the form of a major retrospective exhibition. If we wish to appreciate Van Huysum it is no good looking at his work through the filter an early 20th-century aesthetic prejudice. The purpose of this lecture is to place the artist’s achievement in its true cultural and artistic context. -

The Dutch School of Painting

Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924073798336 CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 924 073 798 336 THE FINE-ART LIBRARY. EDITED BY JOHN C. L. SPARKES, Principal of the National Art Training School, South Kensington - Museum, THE Dutch School Painting. ye rl ENRY HA YARD. TRANSLATED HV G. POWELL. CASSELL & COMPANY, Limited: LONDON, PARIS, NEW YORK ,C- MELBOURNE. 1885. CONTENTS. -•o*— ClIAr. I'AGE I. Dutch Painting : Its Origin and Character . i II. The First Period i8 III. The Period of Transition 41 IV. The Grand Ki'ocii 61 V. Historical and Portrait Painters ... 68 VI. Painters of Genre, Interiors, Conversations, Societies, and Popular and Rustic Scenes . 117 VI [. Landscape Painters 190 VIII. Marine Painters 249 IX. Painters of Still Life 259 X. The Decline ... 274 The Dutch School of Painting. CHAPTER I. DUTCH PAINTING : ITS ORIGIN AND CHARACTER. The artistic energy of a great nation is not a mere accident, of which we can neither determine the cause nor foresee the result. It is, on the contrary, the resultant of the genius and character of the people ; the reflection of the social conditions under which it was called into being ; and the product of the civilisation to which it owes its birth. All the force and activity of a race appear to be concentrated in its Art ; enterprise aids its growth ; appreciation ensures its development ; and as Art is always grandest when national prosperity is at its height, so it is pre-eminently by its Art that we can estimate the capabilities of a people. -

Double Vision: Woman As Image and Imagemaker

double vision WOMAN AS IMAGE AND IMAGEMAKER Everywhere in the modern world there is neglect, the need to be recognized, which is not satisfied. Art is a way of recognizing oneself, which is why it will always be modern. -------------- Louise Bourgeois HOBART AND WILLIAM SMITH COLLEGES The Davis Gallery at Houghton House Sarai Sherman (American, 1922-) Pas de Deux Electrique, 1950-55 Oil on canvas Double Vision: Women’s Studies directly through the classes of its Woman as Image and Imagemaker art history faculty members. In honor of the fortieth anniversary of Women’s The Collection of Hobart and William Smith Colleges Studies at Hobart and William Smith Colleges, contains many works by women artists, only a few this exhibition shows a selection of artworks by of which are included in this exhibition. The earliest women depicting women from The Collections of the work in our collection by a woman is an 1896 Colleges. The selection of works played off the title etching, You Bleed from Many Wounds, O People, Double Vision: the vision of the women artists and the by Käthe Kollwitz (a gift of Elena Ciletti, Professor of vision of the women they depicted. This conjunction Art History). The latest work in the collection as of this of women artists and depicted women continues date is a 2012 woodcut, Glacial Moment, by Karen through the subtitle: woman as image (woman Kunc (a presentation of the Rochester Print Club). depicted as subject) and woman as imagemaker And we must also remember that often “anonymous (woman as artist). Ranging from a work by Mary was a woman.” Cassatt from the early twentieth century to one by Kara Walker from the early twenty-first century, we I want to take this opportunity to dedicate this see depictions of mothers and children, mythological exhibition and its catalog to the many women and figures, political criticism, abstract figures, and men who have fostered art and feminism for over portraits, ranging in styles from Impressionism to forty years at Hobart and William Smith Colleges New Realism and beyond. -

The Vanitas in the Works of Maria Van Oosterwijck & Marian Drew

The Vanitas In The Works Of Maria Van Oosterwijck & Marian Drew Both Maria Van Oosterwijck and Marian Drew have produced work that has been described as the Vanitas. Drew does so as a conscious reference to the historic Dutch genre, bringing it into a contemporary Australian context. Conversely, Van Oosterwijck was actively embedded in the original Vanitas still-life movement as it was developed in 17th century Netherlands. An exploration into the works of Maria Van Oosterwijck and Marian Drew will compare differences in their communication of the Vanitas, due to variations in time periods, geographic context, intended audience and medium. Born in 1630, Maria Van Oosterwijck was a Dutch still-life painter. The daughter of a protestant preacher, she studied under renowned still-life painter Jan Davidsz de Heem from a young age, but Quickly developed an independent style. Her work was highly sort after amongst the European bourgeoisie, and sold to monarchs including Queen Mary, Emperor Leopold and King Louis XIV. Van Oosterwijck painted in the Vanitas genre, and was heavily influenced by Caravaggio’s intense chiaroscuro techniQue, as well as the trompe l’oiel realism popular in most Northern BaroQue painting (Vigué 2003). Marian Drew is a contemporary Australian photographic artist. She is known for her experimentations within the field of photography, notably the light painting techniQue she employs to create a deep chiaroscuro effect. This techniQue also produces an almost painterly effect in the final images, which she prints onto large- scale cotton paper. In Drew’s Australiana/Still Life series, she photographed native road kill next to household items and flora, in the style of Dutch Vanitas and game- painting genres. -

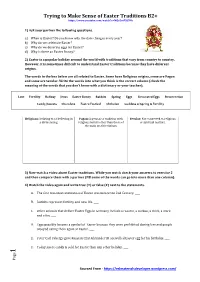

Trying to Make Sense of Easter Traditions B2+

Trying to Make Sense of Easter Traditions B2+ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MQz2mF3jDMc 1) Ask your partner the following questions. a) When is Easter? Do you know why the date changes every year? b) Why do we celebrate Easter? c) Why do we decorate eggs for Easter? d) Why is there an Easter Bunny? 2) Easter is a popular holiday around the world with traditions that vary from country to country. However, it is sometimes difficult to understand Easter traditions because they have different origins. The words in the box below are all related to Easter. Some have Religious origins, some are Pagan and some are Secular. Write the words into what you think is the correct column (check the meaning of the words that you don’t know with a dictionary or your teacher). Lent Fertility Holiday Jesus Easter Bunny Rabbits Spring Eggs Decorated Eggs Resurrection Candy/Sweets Chocolate Eostre Festival Christian Goddess of Spring & Fertility Religious: Relating to or believing in Pagan: A person or tradition with Secular: Not connected to religious a divine being. religious beliefs other than those of or spiritual matters. the main world religions. 3) Now watch a video about Easter traditions. While you watch check your answers to exercise 2 and then compare them with a partner (NB some of the words can go into more than one column). 4) Watch the video again and write true (T) or false (F) next to the statements. A. The first recorded celebration of Easter was before the 2nd Century. ____ B. Rabbits represent fertility and new life. -

Women Artists Utah Museum of Fine Arts • Lesson Plans for Educators October 28, 1998 Table of Contents

Women Artists Utah Museum of Fine Arts • www.umfa.utah.edu Lesson Plans for Educators October 28, 1998 Table of Contents Page Contents 3 Image List 5 Woman Holding a Child with an Apple in its Hand,, Angelica Kauffmann 6 Lesson Plan for Untitled Written by Bernadette Brown 7 Princess Eudocia Ivanovna Galitzine as Flora, Marie Louise Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun 8 Lesson Plan for Flora Written by Melissa Nickerson 10 Jeanette Wearing a Bonnet, Mary Cassatt 12 Lesson Plan for Jeanette Wearing a Bonnet Written by Zelda B. McAllister 14 Sturm (Riot), Käthe Kollwitz 15 Lesson Plan for Sturm Written by Susan Price 17 Illustration for "Le mois de la chevre," Marie Laurencin 18 Lesson Plan for Illustration for "Le mois de la chevre" Written by Bernadette Brown 19 Illustration for Juste Present, Sonia Delaunay 20 Lesson Plan for Illustration for Juste Present Written by Melissa Nickerson 22 Gunlock, Utah, Dorothea Lange 23 Lesson Plan for Gunlock, Utah Written by Louise Nickelson 28 Newsstand, Berenice Abbott 29 Lesson Plan for Newsstand Written by Louise Nickelson 33 Gold Stone, Lee Krasner 34 Lesson Plan for Gold Stone Written by Melissa Nickerson 36 I’m Harriet Tubman, I Helped Hundreds to Freedom, Elizabeth Catlett 38 Lesson Plan for I’m Harriet Tubman Written by Louise Nickelson Evening for Educators is funded in part by the StateWide Art Partnership 1 Women Artists Utah Museum of Fine Arts • www.umfa.utah.edu Lesson Plans for Educators October 28, 1998 Table of Contents (continued) Page Contents 46 Untitled, Helen Frankenthaler 48 Lesson Plan for Untitled Written by Virginia Catherall 51 Fourth of July Still Life, Audrey Flack 53 Lesson Plan for Fourth of July Still Life Written by Susan Price 55 Bibliography 2 Women Artists Utah Museum of Fine Arts • www.umfa.utah.edu Lesson Plans for Educators October 28, 1998 Image List 1. -

NINA YANKOWITZ , Media Artist , N.Y.C

NINA YANKOWITZ , media artist , N.Y.C. www.nyartprojects.com SELETED MUSUEM INSTALLATIONS 2009 The Third Woman interactive film collaboration,Kusthalle Vienna 2009 Crossings Interactive Installation Thess. Biennale Greece Projections, CD Yankowitz&Holden, Dia Center for Book Arts, NYC 2009 Katowice Academy of Art Museum, Poland TheThird Woman Video Tease, Karsplatz Ubahn, project space Vienna 2005 Guild Hall Art Museum, East Hampton, NY Voices of The Eye & Scenario Sounds, distributed by Printed Matter N.Y. 1990 Katonah Museum of Art, The Technological Muse Collaborative Global New Media Team/Public Art Installation Projects, 2008- 2009 1996 The Bass Museum, Miami, Florida PUBLIC PROJECTS 1987 Snug Harbor Museum, Staten Island, N.Yl 1985 Berkshire Museum, Pittsfield, MA Tile project Kanoria Centre for Arts, Ahmedabad, India 2008 1981 Maryland Museum of Fine Arts, Baltimore, MD 1973 Whitney Museum of American Art, NY, Biennia 1973 Brockton Museum, Boston, MA 1972 Larry Aldrich Museum, Ridgefield, Conn. Works on paper 1972 Kunsthaus, Hamburg, Germany, American Women Artists 1972 The Newark Museum, Newark, New Jersey 1972 Indianapolis Museum of Contemporary Art 1972 The Art Institute of Chicago, "American Artists Today" 1972 Suffolk Museum, Stonybrook, NY 1971 Akron Museum of Art, Akron, OH 1970 Museum of Modern Art, NY 1970 Larry Aldrich Museum, Ridgefield, Conn. "Highlights" 1970 Trinity College Museum, Hartford, Conn. ONE PERSON EXHIBITIONS 2005 Kiosk.Edu. Guild Hall Museum, The Garden, E. Hampton, New York 1998 Art In General, NYC. "Scale -

JAN DAVIDSZ. DE HEEM (Utrecht 1606 – 1684 Antwerp) a Still Life Of

VP4587 JAN DAVIDSZ. DE HEEM (Utrecht 1606 – 1684 Antwerp) A Still Life of a Glass of Wine with Grapes, Bread, a Glass of Beer, a peeleD Lemon, Fruit, Onions anD a Herring on a pewter Dish, on a Table DrapeD with a green Cloth SigneD anD DateD upper right: J. De heem f / Ao : 1653 . Oil on panel: 13 x 19 ½ in / 33 x 49.5 cm PROVENANCE ProbablY collection Jean De Jullienne (1686-1766), Chevalier De l’OrDre De St Michel, Paris His posthumous sale, Pierre RemY, Paris, 30th March 1767, lot 126i (240 livres to Montulé) Bertran Collectionii With Duits Ltd., LonDon, in the 1950s From whom bought bY a private collector BY Descent in a private collection, SwitzerlanD, until 2013 To be incluDeD in the forthcoming catalogue raisonné of the work of Jan DaviDsz. De Heem being prepareD bY FreD G. Meijer, as cat. no. A 168. Jan DaviDsz. De Heem (or: Johannes De Heem) was born in Utrecht, where his father, a musician, had moveD from Antwerp. In 1625 the Young painter moveD to LeiDen, where he is recorDeD until 1631. His teacher is unknown, but much of his earliest work (painteD 1625- 1628) shows a strong influence of the MiDDelburg-born Utrecht still-life painter Balthasar van Der Ast. Upon leaving LeiDen, he presumablY spent some time in AmsterDam, but bY March 1636 he had settleD in Antwerp. He paiD his membership fees to the Antwerp guilD for the first time During the administrative Year 1635/36 (which runs from September to September). ProbablY bY 1660 he had settleD in Utrecht again, but he may alreadY have spent longer sojourns there During the previous Years. -

Jan Davidsz. De Heem 1606-1684

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Jan Davidsz. de Heem 1606-1684 Meijer, F.G. Publication date 2016 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Meijer, F. G. (2016). Jan Davidsz. de Heem 1606-1684. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:06 Oct 2021 2 A biography of Jan Davidsz. de Heem (1606-1684)52 The early years in Utrecht From the records of the orphanage board in Utrecht it appears that in February of 1625 a young painter from that city, Jan Davidtsz. van Antwerpen, was planning a journey to Italy.53 Without a shadow of a doubt, this young painter can be identified as the artist we now know as Jan Davidsz. -

Partial Artist List: Nancy Angelo Jerri Allyn Leslie Belt Rita Mae Brown Kathleen Burg Elizabeth Canelake Velene Campbell Carol Chen Judy Chicago Clsuf Michelle T

Doin’ It in Public: Feminism and Art at the Woman’s Building October 1, 2011 – January 28, 2012 Ben Maltz Gallery, Otis College of Art and Design This exhibition presents artwork, graphic design, ephemera, and documentation of work by the artist collectives and individual artists/designers who participated in collaborative projects at the Woman’s Building in Los Angeles between 1973-1991. Artist Collectives/Projects: Ariadne: A Social Network, Feminist Art Workers, Incest Awareness Project, Lesbian Art Project, Mother Art, Natalie Barney Collective, Sisters of Survival, The Waitresses, Chrysalis: A magazine of Women’s Culture, and more. Partial artist list: Nancy Angelo Jerri Allyn Leslie Belt Rita Mae Brown Kathleen Burg Elizabeth Canelake Velene Campbell Carol Chen Judy Chicago Clsuf Michelle T. Clinton Hyunsook Cho Yreina Cervantez Candace Compton Jan Cook Juanita Cynthia Sheila Levrant de Bretteville Johanna Demetrakas Nelvatha Dunbar Mary Beth Edelson Marguerite Elliot Donna Farnsworth Anne Finger Audrey Flack As of 9-27-11 Amani Fliers Nancy Fried Patricia Gaines Josephina Gallardo Diane Gamboa Cristina Gannon Anne Gauldin Cheri Gaulke Anita Green Vanalyne Green Mary Bruns Gonenthal Kirsten Grimstad Chutney Gunderson Berry Brook Hallock Hella Hammid Harmony Hammond Gloria Hajduk Eloise Klein Healy Mary Linn Hughes Annette Hunt Sharon Immergluck Ruth E. Iskin Cyndi Kahn Maria Karras Susan E. King Laurel Klick Deborah Krall Christie Kruse Sheila Levrant de Bretteville Suzanne Lacy Leslie Labowitz-Starus Lili Lakich Linda Lopez Bia