Gender, Inheritance and Sweat in Anthony Trollope's Cousin Henry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Working Paper of Public Health Nr. 06/2014

ISSN: 2279-9761 Working paper of public health [Online] Working Paper of Public Health Nr. 06/2014 La serie di Working Paper of Public Health (WP) dell’Azienda Ospedaliera review). L’utilizzo del peer review costringerà gli autori ad adeguarsi ai di Alessandria è una serie di pubblicazioni online ed Open Access, migliori standard di qualità della loro disciplina, così come ai requisiti progressiva e multi disciplinare in Public Health (ISSN: 2279-9761). Vi specifici del WP. Con questo approccio, si sottopone il lavoro o le idee di un rientrano pertanto sia contributi di medicina ed epidemiologia, sia contributi autore allo scrutinio di uno o più esperti del medesimo settore. Ognuno di di economia sanitaria e management, etica e diritto. Rientra nella politica questi esperti fornirà una propria valutazione, includendo anche suggerimenti aziendale tutto quello che può proteggere e migliorare la salute della per l'eventuale miglioramento, all’autore, così come una raccomandazione comunità attraverso l’educazione e la promozione di stili di vita, così come esplicita al Responsabile Scientifico su cosa fare del manoscritto (i.e. la prevenzione di malattie ed infezioni, nonché il miglioramento accepted o rejected). dell’assistenza (sia medica sia infermieristica) e della cura del paziente. Si Al fine di rispettare criteri di scientificità nel lavoro proposto, la revisione sarà prefigge quindi l’obiettivo scientifico di migliorare lo stato di salute degli anonima, così come l’articolo revisionato (i.e. double blinded). individui e/o pazienti, sia attraverso la prevenzione di quanto potrebbe Diritto di critica: condizionarla sia mediante l’assistenza medica e/o infermieristica Eventuali osservazioni e suggerimenti a quanto pubblicato, dopo opportuna finalizzata al ripristino della stessa. -

THE TROLLOPE CRITICS Also by N

THE TROLLOPE CRITICS Also by N. John Hall THE NEW ZEALANDER (editor) SALMAGUNDI: BYRON, ALLEGRA, AND THE TROLLOPE FAMILY TROLLOPE AND HIS ILLUSTRATORS THE TROLLOPE CRITICS Edited by N. John Hall Selection and editorial matter © N. John Hall 1981 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1981 978-0-333-26298-6 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without permission First published 1981 by THE MACMILLAN PRESS LTD London and Basingstoke Companies and representatives throughout the world ISBN 978-1-349-04608-9 ISBN 978-1-349-04606-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-04606-5 Typeset in 10/12pt Press Roman by STYLESET LIMITED ·Salisbury· Wiltshire Contents Introduction vii HENRY JAMES Anthony Trollope 21 FREDERIC HARRISON Anthony Trollope 21 w. P. KER Anthony Trollope 26 MICHAEL SADLEIR The Books 34 Classification of Trollope's Fiction 42 PAUL ELMER MORE My Debt to Trollope 46 DAVID CECIL Anthony Trollope 58 CHAUNCEY BREWSTER TINKER Trollope 66 A. 0. J. COCKSHUT Human Nature 75 FRANK O'CONNOR Trollope the Realist 83 BRADFORD A. BOOTH The Chaos of Criticism 95 GERALD WARNER BRACE The World of Anthony Trollope 99 GORDON N. RAY Trollope at Full Length 110 J. HILLIS MILLER Self and Community 128 RUTH apROBERTS The Shaping Principle 138 JAMES GINDIN Trollope 152 DAVID SKILTON Trollopian Realism 160 C. P. SNOW Trollope's Art 170 JOHN HALPERIN Fiction that is True: Trollope and Politics 179 JAMES R. KINCAID Trollope's Narrator 196 JULIET McMASTER The Author in his Novel 210 Notes on the Authors 223 Selected Bibliography 226 Index 243 Introduction The criticism of Trollope's works brought together in this collection has been drawn from books and articles published since his death. -

Download Miss Mackenzie, Anthony Trollope, Chapman and Hall, 1868

Miss Mackenzie, Anthony Trollope, Chapman and Hall, 1868, , . DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1boZHoo Ayala's Angel (Sparklesoup Classics) , Anthony Trollope, Dec 5, 2004, , . Sparklesoup brings you Trollope's classic. This version is printable so you can mark up your copy and link to interesting facts and sites.. Orley Farm , Anthony Trollope, 1935, Fiction, 831 pages. This story deals with the imperfect workings of the legal system in the trial and acquittal of Lady Mason. Trollope wrote in his Autobiography that his friends considered this .... The Toilers of the Sea , Victor Hugo, 2000, Fiction, 511 pages. On the picturesque island of Guernsey in the English Channel, Gilliatt, a reclusive fisherman and dreamer, falls in love with the beautiful Deruchette and sets out to salvage .... The Way We Live Now Easyread Super Large 18pt Edition, Anthony Trollope, Dec 11, 2008, Family & Relationships, 460 pages. The Duke's Children , Anthony Trollope, Jan 1, 2004, Fiction, . The sixth and final novel in Trollope's Palliser series, this 1879 work begins after the unexpected death of Plantagenet Palliser's beloved wife, Lady Glencora. Though wracked .... He Knew He Was Right , Anthony Trollope, Jan 1, 2004, Fiction, . Written in 1869 with a clear awareness of the time's tension over women's rights, He Knew He Was Right is primarily a story about Louis Trevelyan, a young, wealthy, educated .... Framley Parsonage , Anthony Trollope, Jan 1, 2004, Fiction, . The fourth work of Trollope's Chronicles of Barsetshire series, this novel primarily follows the young curate Mark Robarts, newly arrived in Framley thanks to the living .... Ralph the Heir , Anthony Trollope, 1871, Fiction, 434 pages. -

A CHRONOLOGY of Trollope's Life and Times Adapted from A

A CHRONOLOGY of Trollope’s life and times Adapted from a chronology in the Penguin editions of Trollope’s Barchester and Palliser novels KEY Events in Trollope’s life Trollope’s writing1 Events in the wider world Works of other writers ____________________________________________________________________________ 1815 Battle of Waterloo Lord George Gordon Byron, Hebrew Melodies ANTHONY TROLLOPE BORN 24 APRIL AT 16 KEPPEL STREET, BLOOMSBURY, THE FOURTH SON OF THOMAS AND FRANCES TROLLOPE. Family moves shortly after to Harrow-on-the-Hill 1823 Trollope attends Harrow as a day-boy (1825) 1825 First public steam railway opened Sir Walter Scott, The Betrothed and The Talisman Sent as a boarder to a private school in Sunbury, Middlesex 1827 Greek War of Independence won in the battle of Navarino Sent to school at Winchester College. His mother sets sail for the USA on 4 November with three of her children 1830 George IV dies; his brother ascends the throne as William IV William Cobbett, Rural Rides Removed from Winchester. Sent again to Harrow until 1834. 1832 Controversial First Reform Act extends the right to vote to approximately one man in five Frances Trollope, Domestic Manners of the Americans 1834 Slavery abolished in the British Empire. Poor Law Act introduces workhouses to England. Edward Bulwer-Lytton, The Last Days of Pompeii Trollope family migrates to Bruges to escape creditors. Anthony returns to London to take up a junior clerkship in the General Post Office. 1835 Halley’s Comet appears ‘Railway mania’ in Britain Robert Browning, Paracelsus Trollope’s father dies in Bruges 1840 Queen Victoria marries Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. -

Cousin Henry Online

mKndx (Download pdf ebook) Cousin Henry Online [mKndx.ebook] Cousin Henry Pdf Free Anthony Trollope audiobook | *ebooks | Download PDF | ePub | DOC Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook 2015-06-24Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 11.00 x .18 x 8.50l, .45 #File Name: 151468854976 pages | File size: 47.Mb Anthony Trollope : Cousin Henry before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Cousin Henry: 2 of 2 people found the following review helpful. Tiresome is the one word that best describes Cousin Henry.By Russell FanelliCousin Henry is the twenty-seventh of Anthony Trollope’s novels I have read and reviewed. It was written three years before Trollope’s death. Sadly, it is not one of Trollope’s finest creations for several reasons.First, the plot of the novel. Squire Indefer Jones of Llanfeare in Wales knows he is dying. He has no children himself, but has adopted his niece Isabel Brodrick, whom he loves dearly. Because she is not a Jones, Squire Indefer has decided to leave the property to Cousin Henry, who is a Jones. Unfortunately, the squire hates and detests Cousin Henry; for that matter, Isabel also thinks her cousin is worthless. Nonetheless, the squire invites Cousin Henry to come down from London to Wales to prepare for his inheritance. The will leaving everything to Henry has been made and all that is left is for the squire to die, which he does not long after Henry has taken up residence at the Llanfeare estate.With his dying breath Squire Indefer whispers to Isabel that he has made all things right. -

Front Matter

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-88636-9 - The Cambridge Companion to Anthony Trollope Edited by Carolyn Dever and Lisa Niles Frontmatter More information the cambridge companion to anthony trollope Anthony Trollope was among the most prolific, popular, and richly diverse writers of the mid-Victorian period, with forty-seven novels and a variety of other writings to his name. Both a serial and a series writer whose novels traversed Ireland, England, Australia, and New Zealand, and genres from realism to science fiction, Trollope also published criticism, short fiction, travel writing, and biography. The Cambridge Companion to Anthony Trollope provides a state-of-the-field review of critical perspectives on his work, with the volume’s essays addressing Trollope’s biography, autobiography, canonical fiction, short stories, and travel writing, as well as surveying diverse topics including gender, sexuality, vulgarity, and the law. A complete list of the books in the series is at the back of this book. © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-88636-9 - The Cambridge Companion to Anthony Trollope Edited by Carolyn Dever and Lisa Niles Frontmatter More information Frontispiece. Anthony Trollope, after Sir Leslie Ward. Chromolithograph, published 1873. Reprinted with the permission of the National Portrait Gallery. NPG d32583. © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-88636-9 - The Cambridge Companion to Anthony Trollope -

Anthony Trollope*S Literary Reputation;

ANTHONY TROLLOPE*S LITERARY REPUTATION; ITS DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDITY by ELLA KATHLEEN GRANT A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for. the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of English The University of British Columbia, October, 1950. This essay attempts to trace the course of Anthony Trollope's literary reputation; to suggest some explan• ations for the various spurts and sudden declines of his popularity among readers and esteem among critics; and to prove that his mid-twentieth century position is not a just one. Drawing largely on Trollope's Autobiography, contemp• orary reviews and essays on his work, and references to it in letters and memoirs, the first chapter describes Trollope's writing career, showing him rising to popu• larity in the late fifties and early sixties as a favour• ite among readers tired of sensational fiction, becoming a byword for commonplace mediocrity in the seventies, and finally, two years before his death, regaining much of his former eminence among older readers and conservative critics. Throughout the chapter a distinction is drawn between the two worlds with which Trollope deals, Barset- shire and materialist society, and the peculiarly dual nature of his work is emphasized. Chapter II is largely concerned with the vicissitudes that Trollope's reputation has encountered since the post• humous publication of his autobiography. During the de• cade following his death he is shown as an object of comp• lete contempt to the Art for Art's Sake school, finally rescued around the turn of the century by critics reacting against the ideals of his detractors. -

The Lawyers of Anthony Trollope

The Lawyers of Anthony Trollope By Henry S. Drinker British novelist Anthony Trollope (1815–1882) wrote, in addition to 47 novels, an autobiogra- phy, a book on Thackeray, five travel books, and 42 short stories. Henry S. Drinker (1880–1965) was a partner in the law firm of Drinker Biddle and was also a musicologist. The essay that follows was an address delivered to members of the Grolier Club in New York City on Nov. 15, 1949. It is presented as it was published by the Grolier Club in 1950, in a book en- titled Two Addresses Delivered to Members of the Grolier Club; the other essay that appears in the book is “Trollope’s America” by Willard Thorp. Only 750 copies of the book were printed. hen I received the delightful invitation to speak Trollope was—perhaps I should say he became—an on Trollope—one of my chief enthusiasms—it extraordinarily careful observer of what was passing was immediately clear to me that my subject around him, and his genius lay in his ability to re-create, must be his lawyers; first, because, as a lawyer, I should with convincing vividness, the types of people whom he Wthus be able to make a more valuable contribution to the observed wherever he chanced to be. He did not create growing store of comment on his writings, and, second, his characters with any desire to point a moral, nor did he because I believe that Trollope’s ideas about and attitude use them as a medium for expressing his own ideas or toward lawyers have not been understood or appreciated epigrams. -

Autobiography of Anthony Trollope

Autobiography of Anthony Trollope Anthony Trollope Autobiography of Anthony Trollope Table of Contents Autobiography of Anthony Trollope.......................................................................................................................1 Anthony Trollope...........................................................................................................................................1 PREFACE......................................................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER I. MY EDUCATION 1815−1834...............................................................................................3 CHAPTER II. MY MOTHER.......................................................................................................................8 CHAPTER III. THE GENERAL POST OFFICE 1834−1841....................................................................12 CHAPTER IV. IRELANDMY FIRST TWO NOVELS 1841−1848........................................................20 CHAPTER V. MY FIRST SUCCESS 1849−1855......................................................................................26 CHAPTER VI. "BARCHESTER TOWERS" AND THE "THREE CLERKS" 1855−1858......................32 CHAPTER VII. "DOCTOR THORNE""THE BERTRAMS""THE WEST INDIES" AND "THE SPANISH MAIN".......................................................................................................................................37 CHAPTER VIII. THE "CORNHILL MAGAZINE" AND "FRAMLEY PARSONAGE".........................41 -

Appendix II Bibliography of Anthony Trollope

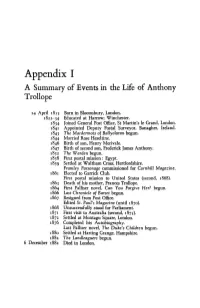

Appendix I A Summary of Events in the Life of Anthony Trollope 24 April 1815 Born in Bloomsbury, London. 1822-34 Educated at Harrow; Winchester. 1834 Joined General Post Office, StMartin's le Grand, London. 1841 Appointed Deputy Postal Surveyor, Banagher, Ireland. 1843 The Macdermots of Ballycloran begun. 1844 Married Rose Heseltine. 1846 Birth of son, Henry Merivale. 1847 Birth of second son, Frederick James Anthony. 1852 The Warden begun. 1858 First postal mission: Egypt. 1859 Settled at Waltham Cross, Hertfordshire. Framley Parsonage commissioned for Cornhill Magazine. 1861 Elected to Garrick Club. First postal mission to United States (second, 1868). 1863 Death of his mother, Frances Trollope. 1864 First Palliser novel, Can You Forgive Her? begun. 1866 Last Chronicle of Barset begun. 1867 Resigned from Post Office. Edited St. Paul's Magazine (until187o). 1868 Unsuccessfully stood for Parliament. 1871 First visit to Australia (second, 1875). 1872 Settled at Montagu Square, London. 1876 Completed his Autobiography. Last Palliser novel, The Duke's Children begun. 188o Settled at Harting Grange, Hampshire. 1882 The Landleagu.ers begun. 6 December 1882 Died in London. Appendix II Bibliography of Anthony Trollope (i) MAJOR WORKS The Macdermots of Ballydoran, 3 vols, London: T. C. Newby, 1847 [abridged in one volume, Chapman & Hall's 'New Edition', 1861]. The Kellys and the O'Kellys: or Landlords and Tenants, 3 vols, London: Henry Colburn, 1848. La Vendee: An Historical Romance, 3 vols, London: Colburn, 185o. The Warden, 1 vol, London: Longman, 1855. Barchester Towers, 3 vols, London: Longman, 1857. The Three Clerks: A Novel, 3 vols, London: Bentley, 1858. -

La Vendée: Trollope's Early Novel of Counterrevolution and Reform

La Vendée: Trollope’s Early Novel of Counterrevolution and Reform By Nicholas Birns Presented at The Trollope Society Winter Lecture, February 21st, 2013 1. Counterrevolution “Counterrevolutionary” as a term emerged in the wake of the French Revolution to de- note not Just those opposed to radical social change but who positively abhorred it and manifested a palpable opposite agenda. This essay will argue that Anthony Trollope, though at first counterrevolutionary in his perspective on social change, became more re- formist in his views in the course of his career, and that Trollope’s deployment of region and place can be seen as an index of this change. Anthony Trollope is usually seen as an anti-Romantic writer, his guying of Lizzie Eu- stace’s love for Shelley in The Eustace Diamonds seen as typical of his disdain. Yet Trollope’s first few novels affiliate themselves with specific 'other’ places, exuding a topicality funda- mentally Romantic. Trollope's 1850 novel La Vendée, about the conservative rural re- sistance to the French Revolution in the early 1790s, is the consummately romantic subject, both in its resistance to universal prescription and its intense affiliation with place. As Trol- lope's sense of place stretches over the ensuing years of his career, from the global (the An- tipodes, the Indies; America) to the local (Devonshire and a specifically provincial setting in Rachel Ray, Wales in Cousin Henry, and of course the Barsetshire novels) the motif of topi- cality is revised to be more inclusive and interchangeable. Yet it retains a referential rela- tion to place that is a transmutation of an earlier, more explicitly counterrevolutionary Romantic one. -

1. INTRODUCTION Bt Steven Amarnick

1 1. INTRODUCTION by Steven Amarnick Originally published in 2015 as part of the Commentary to the First Complete Edition of the extended version of ‘The Duke’s Children’ by the Folio Society, in two limited fine edition formats. NOTES ON THE CUTS “But now I will accept that as courage which I before regarded as arrogance.” With that sentence, The Duke’s Children comes to an abrupt end. Except not quite. Sixty-four words follow in the manuscript—words that Anthony Trollope had intended to publish but reluctantly left out. Preceding this sentence are some 65,000 other words that were cut—over twenty-two per cent of the manuscript. Now in 2015, in the two hundredth year of Trollope’s birth, The Duke’s Children can be read in full for the first time. By restoring his cuts, we restore his original vision, and present the book in a version that is as close as possible to the one he would have sanctioned had he been able to publish it in his typical fashion. It is only in The Duke’s Children (1880), the sixth and final novel of the Palliser series, that the Pallisers actually dominate the narrative. One of the two “her”s in Can You Forgive Her? (1864) is Alice Vavasor, who after much vacillation finally marries. The eponymous hero of Phineas Finn (1869) is a young Irishman who moves to London and fails to marry—though not for lack of trying. He does succeed, at first brilliantly, as a politician, but at the end he returns to the girl waiting for him back home in Killaloe.