Nationalism and Nostalgia in the Tatar Republic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heel and Toe 2012/2013 Number 11

HEEL AND TOE ONLINE The official organ of the Victorian Race Walking Club 2012/2013 Number 11 11 December 2012 VRWC Preferred Supplier of Shoes, clothes and sporting accessories. Address: RUNNERS WORLD, 598 High Street, East Kew, Victoria (Melways 45 G4) Telephone: 03 9817 3503 Hours : Monday to Friday: 9:30am to 5:30pm Saturday: 9:00am to 3:00pm Website: http://www.runnersworld.com.au/ Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/pages/Runners-World/235649459888840 TIM'S WALKER OF THE WEEK Last week's Walker of the Week was shared between Victorian Emmet Brasier and Queenslander Clara Smith who both performed so well in the Australian All Schools Championships in Hobart. This week sees more great walking on the Australian front and I have highlighted 4 of the many outstanding walks for voting. • NSW/AIS walker Luke Adams confirmed his place for next year's IAAF World Championships with a win in the Australian 50km championship last Sunday. Luke won this title in 2010 and was back on the podium again with his time of 3:57:24. • NSWIS walker Ian Rayson also knocked out an A qualifier for next year's IAAF World Championships with his second place time of 4:00:39 in the same race. Ian was in two minds as to whether to do the 50km or the 20km event on Sunday but he obviously made the right choice! • 17 year old Queenslander Jesse Osborne walked a 57 sec PB to win the Junior 10km invitational walk at Fawkner Park, his time of 43:18 a huge improvement on his 44:15, walked at this year's World Walking Cup in Russia. -

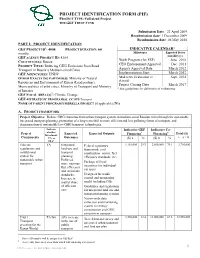

PROJECT IDENTIFICATION FORM (PIF) PROJECT TYPE: Full-Sized Project the GEF TRUST FUND

PROJECT IDENTIFICATION FORM (PIF) PROJECT TYPE: Full-sized Project THE GEF TRUST FUND Submission Date: 22 April 2009 Resubmission date: 1 December 2009 Resubmission date: 06 May 2010 PART I: PROJECT IDENTIFICATION GEF PROJECT ID1: 4008 PROJECT DURATION: 60 INDICATIVE CALENDAR* months Milestones Expected Dates mm/dd/yyyy GEF AGENCY PROJECT ID: 4304 Work Program (for FSP) June 2010 COUNTRY(IES): Russia CEO Endorsement/Approval Dec. 2011 PROJECT TITLE: Reducing GHG Emissions from Road Transport in Russia’s Medium-sized Cities Agency Approval Date March 2012 GEF AGENCY(IES): UNDP Implementation Start March 2012 OTHER EXECUTING PARTNER(S): Ministry of Natural Mid-term Evaluation (if Sept. 2014 planned) Resources and Environment of Russia (Lead partner), Project Closing Date March 2017 Municipalities of pilot cities, Ministry of Transport and Ministry * See guidelines for definition of milestones. of Interior GEF FOCAL AREA (S)2: Climate Change GEF-4 STRATEGIC PROGRAM(s): CC-SP5-Transport NAME OF PARENT PROGRAM/UMBRELLA PROJECT (if applicable):N/A A. PROJECT FRAMEWORK Project Objective: Reduce GHG emissions from urban transport system in medium-sized Russian cities through the sustainable integrated transport planning, promotion of a long-term shift to more efficient and less polluting forms of transport, and demonstration of sustainable low-GHG transport technologies. Indicate Indicative GEF Indicative Co- Project whether Expected Expected Outputs a a Total ($) Investment Financing Financing Components , TA, or Outcomes ($) a % ($) b % c =a -

Cognitive Activity Through English

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kazan Federal University Digital Repository КАЗАНСКИЙ ФЕДЕРАЛЬНЫЙ УНИВЕРСИТЕТ ИНСТИТУТ МЕЖДУНАРОДНЫХ ОТНОШЕНИЙ, ИСТОРИИ И ВОСТОКОВЕДЕНИЯ Л.А. Гизятова, Н.Ф. Плотникова COGNITIVE ACTIVITY THROUGH ENGLISH КАЗАНЬ 2016 УДК 811.111(075) ББК 81.2Англ-923 Г46 Печатается по решению учебно-методической комиссии Института международных отношений, истории и востоковедения Казанского (Приволжского) федерального университета Авторы: преподаватель кафедры английского языка в сфере медицины и биоинженерии Казанского (Приволжского) федерального университета Л.А. Гизятова; кандидат педагогических наук, доцент кафедры иностранных языков и перевода Казанского инновационного университета имени В.Г. Тимирясова (ИЭУП) Н.Ф. Плотникова Рецензенты: кандидат филологических наук, доцент кафедры иностранных языков и перевода Казанского инновационного университета имени В.Г. Тимирясова (ИЭУП) К.Р. Вагнер; кандидат филологических наук, доцент кафедры английского языка в сфере медицины и биоинженерии Казанского (Приволжского) федерального университета А.Р. Заболотская Гизятова Л.А. Г46 Cognitive activity through English: учебное пособие для студентов высших учеб- ных заведений / Л.А. Гизятова, Н.Ф. Плотникова. – Казань: Изд-во Казан. ун-та, 2016. – 116 с. Учебное пособие состоит из десяти уроков, включающих оригинальные тексты по спортивной тематике и упражнения к ним. Структура и содержание пособия соответствуют требованиям программы по английскому языку для неязыковых специальностей высших учебных заведений и предполагают совершенствование навыков чтения, устной и письмен- ной речи по специальности. Пособие рекомендуется для студентов физкультурных специальностей высших учеб- ных заведений. УДК 811.111(075) ББК 81.2Англ-923 © Гизятова Л.А., Плотникова Н.Ф., 2016 © Издательство Казанского университета, 2016 2 ПРЕДИСЛОВИЕ Настоящее пособие предназначено для студентов физкультурных специ- альностей первого и второго курсов. -

REGULATIONS for the 27Th SUMMER UNIVERSIADE 2013 KAZAN – RUSSIA 6 to 17 July 2013

FISU REGULATIONS version June 2012 SU 2013 Kazan, Russia FEDERATION INTERNATIONALE DU SPORT UNIVERSITAIRE INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY SPORTS FEDERATION REGULATIONS FOR THE 27th SUMMER UNIVERSIADE 2013 KAZAN – RUSSIA 6 to 17 July 2013 FISU Secretariat 1 FISU REGULATIONS version June 2012 SU 2013 Kazan, Russia TABLE OF CONTENTS I. GENERAL REGULATIONS .......................................................................................7 1. GENERAL TERMS..........................................................................................7 2. PROGRAMME.............................................................................................11 2.1 Compulsory programme...................................................................11 2.2 Optional sport..................................................................................12 2.3 Preliminary rounds...........................................................................13 2.4 Cancellation.....................................................................................13 2.5 Dates................................................................................................13 3. RESPONSIBILITIES OF FISU..........................................................................13 3.1 Generalities......................................................................................13 3.2 FISU Executive Committee ...............................................................15 3.3 International Control Committee (CIC).............................................16 3.4 International -

The Effective Use of Heritage Sites of the Major Sporting Events in Russia

Proceeding Supplementary Issue: Autumn Conferences of Sports Science. Costa Blanca Sports Science Events, 18-19 December 2020. Alicante, Spain. The effective use of heritage sites of the major sporting events in Russia OLEG ALEKSANDROVICH BUNAKOV1 , DMITRY VLADIMIROVICH RODNYANSKY1, BORIS MOJSHEVICH EIDELMAN1, ELENA VALERIEVNA GRIGORIEVA1, TIMOFEY VASILYEVICH BASHLYKOV2 1Institute of Management, Economics and Finance, Kazan Federal University, Russian Federation 2Department of Economics, Management and Marketing, Kazan Federal University, Russian Federation ABSTRACT This article dwells on the positive and negative experience of using facilities remaining after the major sporting events in the country. The authors analyse the use of stadiums built for the FIFA World Cup, as well as the facilities of Kazan involved during the Universiade 2013. The research resulted in the conclusion about the necessity as far back at the designing stage to study both the relevancy of the sporting venue during the event and its potential usage afterwards. The authors make a point that there is a positive emotional effect, which is revealed in the growth of tourism, and increasing the attractiveness of the territory for local residents. The results obtained can be useful for cities and countries that have yet to host major sports events. Keywords: Heritage sites; Effective use; Sporting events. Cite this article as: Bunakov, O.A., Rodnyansky, D.V., Eidelman, B.M., Grigorieva, E.V., & Bashlykov, T.V. (2021). The effective use of heritage sites of the major sporting events in Russia. Journal of Human Sport and Exercise, 16(2proc), S427-S433. doi:https://doi.org/10.14198/jhse.2021.16.Proc2.28 1 Corresponding author. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research, volume 131 “New Silk Road: Business Cooperation and Prospective of Economic Development” (NSRBCPED 2019) Tourism as a Factor of City Development in the Post- Industrial Economy Svetlana R. Khusnutdinova Daniiar F. Sadretdinov Department of theory and methodology of geographical and Department of Socio-Economic and Humanitarian environmental education Disciplines Kazan Federal University Volga Region State Academy of Physical Culture, Sport and Kazan, Russia Tourism [email protected] Kazan, Russia [email protected] Rustem R. Khusnutdinov Physics department Kazan State Power Engineering Kazan, Russia [email protected] Abstract—The article is devoted to the study of city tourism. The growth of tourist flow means opportunity for residents City tourism is now practiced across the whole world; however, it to expand business, to improve income and create new is undervalued in city management as well as in academic activities and jobs. There are two key aspects: large cities and research. City tourism is not a new form of tourism as such; as a agglomerations become most important destination of tourist matter of fact, people have always visited cities with a variety of flows and tourism becomes important component of city purposes (business, recreation, to visit friends or relatives etc.). economy [3]. The change in the approach has taken place in post-industrial economy, when its importance in developing the city economy in In post-industrial era the large cities needs to develop terms of social, cultural, employment and revenue improvement tourism industry in the cities. On the one hand, cities have a has become apparent. -

Kazan 2013 Universiade.Xlsm

Kazan 2013 Summer Universiade Universiade Games - Tennis MEN'S SINGLES MAIN DRAW (96&128) Dates City, Country ITF Referee 8-16 July 2013 Kazan, Russia Gary Au-Yeung St. Rank Seed Family Name First name Nationality 2nd Round 3rd Round 4th Round Quarterfinalists 1 DA 179 1 KRAVCHUK Konstantin RUS KRAVCHUK Page 1(3) 2 DA 76 BYE a a KRAVCHUK 3 BYE THOMPSON 64 62 4 DA 25 THOMPSON Samuel AUS b Umpire a KRAVCHUK 5 DA 63 MULLENGA Frichard ZAM MULLENGA 64 62 6 BYE a b LEE-DAIGLE 7 DA 76 BYE LEE-DAIGLE 61 61 8 DA 28 LEE-DAIGLE Chistiaan Ting CAN b Umpire a KRAVCHUK 9 DA 56 RAKHMATOV Anvar TJK RAKHMATOV 61 62 10 DA 76 BYE a b LAM 11 BYE LAM W/O 12 DA 35 LAM Siu-Fai HKG b Umpire b PAZICKY 13 DA 44 MUNKHBAYAR Margadmun MGL MUNKHBAYAR 64 63 14 BYE a b PAZICKY 15 DA 76 BYE PAZICKY 61 60 16 DA 1084 14 PAZICKY Michal SVK b 17 DA 950 10 FILIN Pavel BLR FILIN 18 DA 76 BYE a a FILIN 19 BYE ZOUGHEIB 60 60 20 DA 38 ZOUGHEIB Michel LIB b Umpire a FILIN 21 DA 68 AL MAHRUQI Ahmed OMA AL MAHRUQI 26 64 75 22 BYE a b WIESINGER 23 DA 76 BYE WIESINGER 60 60 24 DA 1434 20 WIESINGER Joao BRA b Umpire a FILIN 25 DA 34 WHITBREAD Scott Robert GBR WHITBREAD 64 64 26 DA 76 BYE a b JOHNSON 27 BYE JOHNSON 64 64 28 DA 62 JOHNSON Eric USA b Umpire b KATAYAMA 29 DA 32 ROCHER Sebastien FRA ROCHER 64 62 30 DA 59 ERNEPESOV Aleksandr TKM a 76(2) 76(1) b KATAYAMA 31 DA 76 BYE KATAYAMA 64 76(1) 32 DA 519 6 KATAYAMA Sho JPN b 33 DA 332 3 LIM Yong-Kyu KOR LIM 34 DA 76 BYE a a LIM 35 BYE SYED NAGUIB 63 62 36 DA 41 SYED NAGUIB Syed MohamadMAS Agil b Umpire a LIM 37 DA 53 THIYAMBARAWATTA -

2013 Summer Universiade Kazan, Russia – July 6-17, 2013

2013 Summer Universiade Kazan, Russia – July 6-17, 2013 Table Tennis Canada will manage the qualification system and enter Team Canada in the 2013 Summer Universiade. Players who meet the eligibility requirement (below) will qualify for the Canadian Team through the Canadian Ranking/Rating system by 1 – being a member of a provincial association in good standing, and registering for the qualification no later than January 15, 2013. Players can register by e-mail to [email protected] to register; players must include payment of $50 either through PayPal or by cheque (mail to: TTCAN, 18 Louisa St. #230, Ottawa, ON, K1R 6Y6). Players who are not registered will not be accepted as members of the Canadian team. 2 - Players who register to qualify for the Canadian team must compete in at least 3 sanctioned competitions (minimum **) between January 15, 2013 and May 1, 2013, the results of which are entered in the Canadian Ranking/Rating system or the ITTF World ranking system. 3 - TTCAN will publish the ranking of the registered players on February 5, March 5, April 5 and May 5, so players can follow their progress. 4 - The May 5 ranking will determine the make-up of the team. The top 5 players on the men’s and on the women’s ranking of student athletes (registered by January 15, 2013) will form the Canadian team. 5 – For 2013, CIS is providing subsidized accommodation according to the number of carded athletes that participated in the 2011 Summer Universiade. Therefore, TTCAN has been allocated subsidized accommodation for 1 athlete. -

EUSA Magazine 2013

EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY SPORTS ASSOCIATION YEAR MAGAZINE 2013 CONTENTS Page 01 EUSA Structures 4 02 European Universities Championships 8 03 EUSA Patronage 46 04 EUSA Conferences and Projects 52 05 EU Initiatives 70 06 Our Partners 78 07 Cooperation and Alliances 98 08 Future Program 104 2 EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY SPORTS ASSOCIATION YEAR MAGAZINE 2013 www.eusa.eu WELCOME ADDress Dear friends, With great pleasure and pride I am writing General Assembly which was held in Funchal, Adam Roczek, this Welcome Address, presenting the annual Madeira in March 2013, an international EUSA President EUSA Magazine for the year 2013. I invite you conference was organised, presenting new to check the highlights we have prepared and opportunities for university sport. The topic do not hesitate to check our website for more of education will be further developed in the information. future as well, also through a newly established Educational Services Commission. We paid European University Sports Association – special recognition to the special achievements of EUSA concluded the year 2013 very positively, individuals, teams and organisations by awarding undoubtedly due to engagement of our member them at the Gala, also held in Madeira. At this associations, dedication of the members of occasion let me sincerely thank our Portuguese Executive Committee, EUSA Commissions, hosts for all their efforts and hospitality. Office, EUSA event organisers, volunteers and entire EUSA Family, with strong support of our The International University Sports Federation – partners. Lots of new records have been set, FISU as the world umbrella organisation in the namely in terms of organised sports events and field of university sport remains a strong partner participation number & structure. -

FISU Conference ”University and Olympic Sport: Two Models – One Goal?”

July 14 – 17, 2013 FISU Conference ”University and Olympic Sport: two models – one goal?” www.kazan2013.com 2nd Announcement Dear Participants! The Universiade and the FISU Conference in Kazan 2013 will coin- cide with the 90th anniversary of the First World University Games in Paris 1923, linked with the First International Scientific Conference on University Sport with the main topic: “Sportsmanship, a direct heritage of the new Olympic spirit”. Today’s youth represents the largest cohort of young people in human history. This generation has access to the greatest opportu- nities as well as unprecedented risks, in a world which is currently facing multiple challenges. Now more than ever, we need to prepare tomorrow’s decision makers. - FISU firmly believes that, as part of higher education, sportsman- ship fosters and enlightens student-athletes, helps them perform at the highest level of sporting and academic excellence, and provides them with emotion and inspiration for the joy of life; - FISU re-affirms with force that University Sport can play a major role in promoting active citizenship engagement, social integration, a healthy way of life and global consciousness among the youth; - FISU considers that through highly-competitive sporting activi- ties, young people tend to acquire sharply trained minds and strong wills to overcome difficulties. A powerful international multisport event, the Kazan 2013 Universi- ade should provide an excellent opportunity to foster the outstand- ing world leaders of the future. The theme of the Kazan 2013 FISU Conference, “University and Olympic Sport: two models – one goal?”, will offer a wide range of lectures on the history and spirit of the Olympic and International University Sport movements, as well as information, discussions and exchanges about sportsmanship (fighting spirit, fair play and friend- ship) as a truly meaningful and epoch-making opportunity to foster the leaders of the future in competitive environments. -

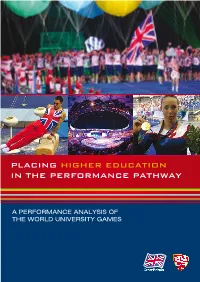

Placing Higher Education in the Performance Pathway

Placing HigHer education in tHe Performance PatHway A performAnce AnAlysis of the World University GAmes Contents Foreword Foreword 3 With thanks to: Great Britain has a long and proud history of student sport, and the World Universities Contribution to Olympic Performance 4 University Games (the Universiade) represents the pinnacle of competition for our student sportsmen and women. Introduction to the World University Games 6 n Ed Smith n Lisa Dobriskey Shenzhen 2011 7 The Universiade is the second largest multisport event in the World, with more n Gemma Gibbons than 10,000 participants from 150+ countries in more than 20 sports. The Performance Analysis 8 n FISU – The International University Archery 9 Universiade represents probably the experience most akin to an Olympics in Sports Federation terms of scale, village life and competition standard. Athletics 10 n Podium - The FE and HE unit for Badminton 12 London 2012 Games The Great Britain teams have a track record of providing elite athletes Women’s Basketball 12 n Great Britain representatives and support staff of the future their first taste of a world-class, large-scale international multi-sports environment. Diving 13 to FISU; Tom Crisp, Jeanette Johnson, Frederick Meredith, Fencing 14 London 2012 Olympic medallist Gemma Gibbons is a great example of this. Alison Odell, Alan Sharp, Ian The experiences of participating at two World University Games, in Gemma’s Case Study: Gemma Gibbons 15 Smyth, John Warnock & Zena Artistic Gymnastics 16 own words, prepared her for a major event on the scale of the Olympic Games, Wooldridge allowing her to perform to her best and subsequently win a silver medal. -

KAZAN ARENA Kazan Arena

038 REPORT KAZAN ARENA Kazan Arena. They asked me if my company could provide technical solutions and support should they get the contract,” explained Andrey. “After the first design Company: Outline was made, we seNt it to the Outline representative in Russia, who reviewed the Location: Kazan, Russia system, corrected some weak points in loudspeaker connections and checkED the specifications.” After a failed first attempt to hold the Summer Universiade in 2011, the Mayor According to Sergey Chernitsyn, Project Director at Komis, there were two man- of Kazan Ilsur Metshin and the President of the Republic of Tatarstan Rustam ufacturers to choose between for the audio system. Using Andrey’s designs, the Minnikhanov were successful two years later in their bid for the 2013 Summer team tried out the loudspeaker set-ups from both manufacturers. The decision to Universiade in the Kazan Arena. Kazan-based construction company, Komis won opt for Outline was motivated by the satisfactory SPL levels and even coverage the the tender to design, supply, install and set up the audio system within the stadium. loudspeakers produced. The Kazan Arena has not only played host to the 2013 Summer Universiade, but “Outline amplifiers were chosen simply because the input and output character- will be the location of several high-profile matches during the 2018 World Cup in istics, and the parametres of the amplifiers and the cabinets, had been set up Russia, so the audio set-up needed to adhere to all of FIFA’s technical parametres and verified,” Sergey explained. “Outline products were optimal for this installation and specifications.