Sample BIP and MP for Projects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Silent Crisis in Congo: the Bantu and the Twa in Tanganyika

CONFLICT SPOTLIGHT A Silent Crisis in Congo: The Bantu and the Twa in Tanganyika Prepared by Geoffroy Groleau, Senior Technical Advisor, Governance Technical Unit The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), with 920,000 new Bantus and Twas participating in a displacements related to conflict and violence in 2016, surpassed Syria as community 1 meeting held the country generating the largest new population movements. Those during March 2016 in Kabeke, located displacements were the result of enduring violence in North and South in Manono territory Kivu, but also of rapidly escalating conflicts in the Kasaï and Tanganyika in Tanganyika. The meeting was held provinces that continue unabated. In order to promote a better to nominate a Baraza (or peace understanding of the drivers of the silent and neglected crisis in DRC, this committee), a council of elders Conflict Spotlight focuses on the inter-ethnic conflict between the Bantu composed of seven and the Twa ethnic groups in Tanganyika. This conflict illustrates how representatives from each marginalization of the Twa minority group due to a combination of limited community. access to resources, exclusion from local decision-making and systematic Photo: Sonia Rolley/RFI discrimination, can result in large-scale violence and displacement. Moreover, this document provides actionable recommendations for conflict transformation and resolution. 1 http://www.internal-displacement.org/global-report/grid2017/pdfs/2017-GRID-DRC-spotlight.pdf From Harm To Home | Rescue.org CONFLICT SPOTLIGHT ⎯ A Silent Crisis in Congo: The Bantu and the Twa in Tanganyika 2 1. OVERVIEW Since mid-2016, inter-ethnic violence between the Bantu and the Twa ethnic groups has reached an acute phase, and is now affecting five of the six territories in a province of roughly 2.5 million people. -

Democratic Republic of the Congo of the Congo Democratic Republic

Democratic Republic of the Congo of the Congo Democratic Republic Main objectives Impact • UNHCR provided international protection to some In 2005, UNHCR aimed to strengthen the protection 204,300 refugees in the DRC of whom some 15,200 framework through national capacity building, registra- received humanitarian assistance. tion, and the prevention of and response to sexual and • Some of the 22,400 refugees hosted by the DRC gender-based violence; facilitate the voluntary repatria- were repatriated to their home countries (Angola, tion of Angolan, Burundian, Rwandan, Ugandan and Rwanda and Burundi). Sudanese refugees; provide basic assistance to and • Some 38,900 DRC Congolese refugees returned to locally integrate refugee groups that opt to remain in the the DRC, including 14,500 under UNHCR auspices. Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC); prepare and UNHCR monitored the situation of at least 32,000 of organize the return and reintegration of DRC Congolese these returnees. refugees into their areas of origin; and support initiatives • With the help of the local authorities, UNHCR con- for demobilization, disarmament, repatriation, reintegra- ducted verification exercises in several refugee tion and resettlement (DDRRR) and the Multi-Country locations, which allowed UNHCR to revise its esti- Demobilization and Reintegration Programme (MDRP) mates of the beneficiary population. in cooperation with the UN peacekeeping mission, • UNHCR continued to assist the National Commission UNDP and the World Bank. for Refugees (CNR) in maintaining its advocacy role, urging local authorities to respect refugee rights. UNHCR Global Report 2005 123 Working environment Recurrent security threats in some regions have put another strain on this situation. -

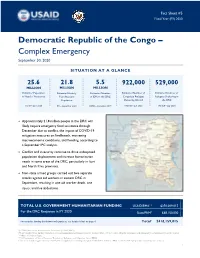

DRC Complex Emergency Fact Sheet #5 09.30.2020

Fact Sheet #5 Fiscal Year (FY) 2020 Democratic Republic of the Congo – Complex Emergency September 30, 2020 SITUATION AT A GLANCE 25.6 21.8 5.5 922,000 529,000 MILLION MILLION MILLION Estimated Population Estimated Acutely Estimated Number Estimated Number of Estimated Number of in Need of Assistance Congolese Refugees Refugees Sheltering in Food Insecure of IDPs in the DRC Population Sheltering Abroad the DRC OCHA – June 2020 UNHCR – July 2020 UNHCR – July 2020 IPC – September 2020 OCHA – December 2019 Approximately 21.8 million people in the DRC will likely require emergency food assistance through December due to conflict, the impact of COVID-19 mitigation measures on livelihoods, worsening macroeconomic conditions, and flooding, according to a September IPC analysis. Conflict and insecurity continue to drive widespread population displacement and increase humanitarian needs in some areas of the DRC, particularly in Ituri and North Kivu provinces. Non-state armed groups carried out two separate attacks against aid workers in eastern DRC in September, resulting in one aid worker death, one injury, and five abductions. TOTAL U.S. GOVERNMENT HUMANITARIAN FUNDING USAID/BHA1,2 $350,009,015 For the DRC Response in FY 2020 State/PRM3 $68,150,000 For complete funding breakdown with partners, see detailed chart on page 6 Total4 $418,159,015 1USAID’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance (USAID/BHA) 2 Total USAID/BHA funding includes non-food humanitarian assistance from the former Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance and emergency food assistance from the former Office of Food for Peace. 3 U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (State/PRM) 4 This total includes approximately $23,833,699 in supplemental funding through USAID/BHA and State/PRM for COVID-19 preparedness and response activities. -

Musebe Artisanal Mine, Katanga Democratic Republic of Congo

Gold baseline study one: Musebe artisanal mine, Katanga Democratic Republic of Congo Gregory Mthembu-Salter, Phuzumoya Consulting About the OECD The OECD is a forum in which governments compare and exchange policy experiences, identify good practices in light of emerging challenges, and promote decisions and recommendations to produce better policies for better lives. The OECD’s mission is to promote policies that improve economic and social well-being of people around the world. About the OECD Due Diligence Guidance The OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas (OECD Due Diligence Guidance) provides detailed recommendations to help companies respect human rights and avoid contributing to conflict through their mineral purchasing decisions and practices. The OECD Due Diligence Guidance is for use by any company potentially sourcing minerals or metals from conflict-affected and high-risk areas. It is one of the only international frameworks available to help companies meet their due diligence reporting requirements. About this study This gold baseline study is the first of five studies intended to identify and assess potential traceable “conflict-free” supply chains of artisanally-mined Congolese gold and to identify the challenges to implementation of supply chain due diligence. The study was carried out in Musebe, Haut Katanga, Democratic Republic of Congo. This study served as background material for the 7th ICGLR-OECD-UN GoE Forum on Responsible Mineral Supply Chains in Paris on 26-28 May 2014. It was prepared by Gregory Mthembu-Salter of Phuzumoya Consulting, working as a consultant for the OECD Secretariat. -

Mecanisme De Referencement

EN CAS DE VIOLENCE SEXUELLE, VOUS POUVEZ VOUS ORIENTEZ AUX SERVICES CONFIDENTIELLES SUIVANTES : RACONTER A QUELQU’UN CE QUI EST ARRIVE ET DEMANDER DE L’AIDE La/e survivant(e) raconte ce qui lui est arrivé à sa famille, à un ami ou à un membre de la communauté; cette personne accompagne la/e survivant(e) au La/e survivant(e) rapporte elle-même ce qui lui est arrivé à un prestataire de services « point d’entrée » psychosocial ou de santé OPTION 1 : Appeler la ligne d’urgence 122 OPTION 2 : Orientez-vous vers les acteurs suivants REPONSE IMMEDIATE Le prestataire de services doit fournir un environnement sûr et bienveillant à la/e survivant(e) et respecter ses souhaits ainsi que le principe de confidentialité ; demander quels sont ses besoins immédiats ; lui prodiguer des informations claires et honnêtes sur les services disponibles. Si la/e survivant(e) est d'accord et le demande, se procurer son consentement éclairé et procéder aux référencements ; l’accompagner pour l’aider à avoir accès aux services. Point d’entrée médicale/de santé Hôpitaux/Structures permanentes : Province du Haut Katanga ZS Lubumbashi Point d’entrée pour le soutien psychosocial CS KIMBEIMBE, Camps militaire de KIMBEIMBE, route Likasi, Tel : 0810405630 Ville de Lubumbashi ZS KAMPEMBA Division provinciale du Genre, avenue des chutes en face de la Division de Transport, HGR Abricotiers, avenue des Abricotiers coin avenue des plaines, Q/ Bel Air, Bureau 5, Centre ville de Lubumbashi. Tel : 081 7369487, +243811697227 Tel : 0842062911 AFEMDECO, avenue des pommiers, Q/Bel Air, C/KAMPEMBA, Tel : 081 0405630 ZS RUASHI EASD : n°55, Rue 2, C/ KATUBA, Ville de Lubumbashi. -

DRC Humanitarian Situation Report

DRC Humanitarian Situation Report Photo: UNICEF DRC Oatway July 2019 SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights 1,260,000*Internally Displaced Persons • In July, UNICEF’s Rapid Response to Movements of Population (IDPs) (HPR 2019) (RRMP) mechanism provided 95,814 persons with essential * Estimate for 2019 household items and shelter materials 7,500,000 children in need of humanitarian assistance (OCHA, HRP 2019) • Multiple emergencies in the provinces of Ituri, South Kivu, Kwango, and Mai Ndombe (Yumbi territory) are heavily underfunded. This gap impacts UNICEF’s response to the 1,400,000 children are suffering from Severe emergencies and prevent children from accessing their basic Acute malnutrition (DRC Nutrition Cluster, January 2019) rights, such as education, child protection, and nutrition 13,542 cases of cholera reported since January st • Ebola outbreak: as of 31 of July 2019, 2,687 total cases of 2019 (Ministry of Health) Ebola, 2,593 confirmed cases and 1,622 deaths linked to Ebola have been recorded in the provinces of North Kivu and 137,154 suspect cases of measles reported since Ituri. January (Ministry of Health) UNICEF Appeal 2019 UNICEF’s Response with Partners US$ 326 Million 25% of required funds available UNICEF Sector/Cluster 2019 DRC HAC FUNDING UNICEF Total Cluster Total STATUS* Target Results* Target Results* Funds received Nutrition: # of children with SAM 911,907 124,888 986,708 365,444 current year: Carry- admitted for therapeutic care $38.1M forward Health: # of children in amount humanitarian situations 1,028,959 1,034,550 -

Democratic Republic of Congo: Cholera Outbreak in Katanga And

Democratic Republic of Congo: Cholera outbreak in DREF Operation n° MDRCD005 GLIDE n° EP-2008-000245-COD Katanga and Maniema 16 December, 2008 provinces The International Federation’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) is a source of un-earmarked money created by the Federation in 1985 to ensure that immediate financial support is available for Red Cross and Red Crescent response to emergencies. The DREF is a vital part of the International Federation’s disaster response system and increases the ability of national societies to respond to disasters. CHF 173,430 (USD 147,449 or EUR 110,212) has been allocated from the Federation’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) to support the Red Cross of the Democratic Republic of the Congo in building its cholera outbreak management capacities in two provinces, namely Maniema and Katanga, and providing assistance to some 600’000 beneficiaries. Un-earmarked funds to repay DREF are encouraged. Summary: Although this DREF bulletin describes the situation in four provinces (North and South Kivu, Maniema and Katanga), the proposed operation will focus only on two provinces (Maniema and Katanga). This is because North and South Kivu, due to ongoing conflict, the RCDRC is working with the ICRC as lead agency. Therefore, all cholera response activities in those two provinces will be covered by ICRC and all cholera response activities in those two provinces will not be covered by this DREF operation. Since early October 2008, high morbidity and mortality rates associated with a cholera epidemic outbreak have been registered in the Maniema, Katanga, North and South Kivu provinces. -

Review of the National Program for Onchocerciasis Control in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease Review Review of the National Program for Onchocerciasis Control in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Jean-Claude Makenga Bof 1,* , Fortunat Ntumba Tshitoka 2, Daniel Muteba 2, Paul Mansiangi 3 and Yves Coppieters 1 1 Ecole de Santé Publique, Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB), Route de Lennik 808, 1070 Brussels, Belgium; [email protected] 2 Ministry of Health: Program of Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTD) for Preventive Chemotherapy (PC), Gombe, Kinshasa, DRC; [email protected] (F.N.T.); [email protected] (D.M.) 3 Faculty of Medicine, School of Public Health, University of Kinshasa (UNIKIN), Lemba, Kinshasa, DRC; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +32-493-93-96-35 Received: 3 May 2019; Accepted: 30 May 2019; Published: 13 June 2019 Abstract: Here, we review all data available at the Ministry of Public Health in order to describe the history of the National Program for Onchocerciasis Control (NPOC) in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Discovered in 1903, the disease is endemic in all provinces. Ivermectin was introduced in 1987 as clinical treatment, then as mass treatment in 1989. Created in 1996, the NPOC is based on community-directed treatment with ivermectin (CDTI). In 1999, rapid epidemiological mapping for onchocerciasis surveys were launched to determine the mass treatment areas called “CDTI Projects”. CDTI started in 2001 and certain projects were stopped in 2005 following the occurrence of serious adverse events. Surveys coupled with rapid assessment procedures for loiasis and onchocerciasis rapid epidemiological assessment were launched to identify the areas of treatment for onchocerciasis and loiasis. -

WHO's Response to the 2018–2019 Ebola Outbreak in North Kivu and Ituri, the Democratic Republic of the Congo

WHO's response to the 2018–2019 Ebola outbreak in North Kivu and Ituri, the Democratic Republic of the Congo Report to donors for the period August 2018 – June 2019 2 | 2018-2019 North Kivu and Ituri Ebola virus disease outbreak: WHO report to donors © World Health Organization 2019 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”. Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WHO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)

Democratic Republic of the Congo Humanitarian Situation Report No. 04 © UNICEF/Kambale Reporting Period: April 2020 Highlights Situation in Numbers 9,100,000 • After 52 days without any Ebola confirmed cases, one new Ebola children in need of case was reported in Beni, North Kivu province on the 10th of April humanitarian assistance 2020, followed by another confirmed case on the 12th of April. UNICEF continues its response to the DRC’s 10th Ebola outbreak. (OCHA, HNO 2020) The latest Ebola situation report can be found following this link 15,600,000 • Since the identification of confirmed COVID-19 cases in the DRC, people in need schools have closed across the country to limit the spread of the (OCHA, HNO 2020) virus. Among other increased needs, the COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbates the significant needs in education related to access to quality education. The latest COVID-19 situation report can be found 5,010,000 following this link Internally displaced people (HNO 2020) • UNICEF has provided life-saving emergency packages in NFI/Shelter 7,702 to more than 60,000 households while ensuring COVID-19 mitigation measures. cases of cholera reported since January (Ministry of Health) UNICEF’s Response and Funding Status UNICEF Appeal 2020 14% US$ 262 million 12% 38% Funding Status (in US$) Funds 15% received Carry- $14.2 M 50% forward, $28.8M 16% 53% 34% Funding 15% gap, $220.9 M 7% 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% 1 Funding Overview and Partnerships UNICEF appeals for US$ 262M to sustain the provision of humanitarian services for women and children in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). -

Geographic Access to Health Facilies in North and South Kivu, Democrac

INTRODUCTION Geographic Access to Health The Democratic Republic of the Congo has experienced a decade Facilies in North and South Kivu, of conflict that has decimated health infrastructure. In much of the country, access to health sites Democrac Republic of the Congo requires a 1‐2 day walk without FINDINGS AND LIMITATIONS North Kivu roads. In the Kivus, at the epicen‐ ter of the humanitarian crisis and The analysis of the raster and town rankings found two things: first, it funding, and with the largest pop‐ identified specific physical areas (shown in shades of red and blue on left ulation outside of Kinshasa, access map) that are either accessible or inaccessible to health facilities, given lack of roads, high slope of terrain and physical distance from health struc‐ Villages in the is better but still severely lacking. Kivus ranked by While lack of data prevents us tures. The same is visualized in more detail for specific towns on the map accessibility to from knowing the type or quality on right. The two together provide a good guide to which villages and re‐ health structures of care provided at each site, with gions in the Kivus are least accessible to existing health structures. GIS we can analyze the physical There was a strong correlation between existing towns, road networks accessibility of villages to health and health structures, but a few areas (southeast area of South Kivu) did structures in North and South Kivu not correlate, suggesting either incomplete health site data or lack of ac‐ provinces. cess. If we had greater confidence in the data we could assert that these villages do not have adequate access to health facilities. -

( Gossypium Sp.) Breeding Experiments in Kivu, Eastern

An appraisal of genotypes performance in cotton (Gossypium sp.) breeding experiments in Kivu, Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo Bin Mushambanyi Théodore Munyuli1 and Jumapili2 1 Biology Department, National Center for Research in Natural Sciences, CRSN-Lwiro, D.S. Bukavu, Kivu DR CONGO 2 C*Société Congolaise du développement de la culture cotonnière au Congo-Kinshasa, Cotonnière du Lac, Uvira, Kivu DR CONGO Correspondence author [email protected] /[email protected] An appraisal of genotypes performance in cotton (Gossypium sp.) breeding experiments in Kivu, Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo ABSTRACT important economic and industrial crops since colo- nial time. They continue to generate important income The ultimate aim of a crop improvement program to farmer in DRCongo, through exportation and sales of the products at the local and regional markets. In is the development of improved crop varieties and 1994, it was estimated by DRCongo government that their release for production. Before lines are re- more than 2.7% of annual income of farmers in Kivu, leased as superior performing types, they are tested Kasai and Oriental provinces, was from cotton in multilocational and macroplot experiments for cultivation.(Fisher,1917; Jurion,1941; Neirink,1948; several years. Such zonal trials identify which line Kanff,1946; Vrijdagh,1936). Cotton is very important is best for what environment. The identification of and had played a valuable role in the development of animal industries (cattle and poultry industry) in the superior line is based on an assessment of differ- DRCongo; especially by providing foodstuffs (cotton ences among line means and their statistical sig- seeds, cattle cakes) necessary to elaborate rations of nificance.