The Chemistry of Jellybeans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Graham Cracker Mint Fudge by Cuchina

Graham Cracker Mint Fudge by Cuchina Crust Ingredients 1 ¾ cups graham cracker crumbs or 10 whole graham crackers* 6 tablespoons melted salted butter 1/4 cup granulated sugar * If using the whole graham crackers, place them in a re-sealable plastic bag and crust with your rolling pin. Instructions Preheat oven to 350 degrees F. In a small microwave safe bowl, cut butter into cubes, cover with small Cuchina Safe Lid, microwave on high for 35 to 40 sec., do not overcook. In medium bowl combine graham crackers, sugar, and melted butter; blend until the texture of coarse meal. Line pan with non-stick foil or parchment paper, using your hands or a flat-bottomed glass, press the mixture evenly into a 9”x 9” pan. If the crumb mixture will not stick where you press them; just add a tablespoon of water to the mix. Bake for approximately 8 to 10 minutes. Chill crust for an hour before adding fudge to help prevent crumbling when serving. Fudge Ingredients 1 ( 10oz ) bag milk chocolate chips (1 ¾ cup) 1 ( 10oz )bag mint chocolate chips (1 ¾ cup) 1 (14oz) can sweetened condensed milk 1⁄4 cup butter 1 tsp. Vanilla 1 cup chopped walnuts (Optional if not doing the crust, add to melted fudge mixture) Instructions Place chocolate chips, condensed milk, butter and vanilla in a microwave safe bowl, cover with large Cuchina Safe Lid. Microwave on medium heat for 1 minute then stir, continue heating and stirring every 30 seconds until chocolate is completely melted. This prevents the chocolate from burning. -

BEST IMPORTS the World’S Finest Confectionery PRICE LIST SPRING/SUMMER 2019 Prices Effective 1St March 2019 BES T IMPORTS the World’S Finest Confectionery

® BEST IMPORTS The world’s finest confectionery PRICE LIST SPRING/SUMMER 2019 Prices effective 1st March 2019 BES T IMPORTS The world’s finest confectionery INDEX Jelly Belly Beans Page 3 BeanBoozled ® Page 16 BeanBoozled ® Minions Range Page 19 Jurassic World Page 20 DC Comic Super Hero Range Page 21 Harry Potter™ Candy Page 22 Pet Gummi Candies Page 25 Sport Beans ® Page 26 Jelly Belly Bean Accessories Page 27 Jelly Belly Bean Display Stands Page 29 Adams & Brooks Pops Page 31 Lollipop Display Stands Page 33 Peppa Pig™ Lollies Page 34 All Natural Candy Canes Page 35 Chocca Mocca Page 36 Loacker Wafer Biscuits Page 37 Pan Ducale Biscotti & Cantuccini Page 41 BES T IMPORTS 2 The world’s finest confectionery Jelly Belly® Beans Bulk SINGLE Flavours Jelly Belly® jelly beans are not your ordinary jelly beans. They are smaller, softer and brighter, with true-to-life mouth-watering flavours in both the centre and the shell. We use real ingredients whenever possible. Get Real. Get Jelly Belly®. Available in 4 x 1 kg bag outer cases ALL JELLY BELLY® BEANS ARE: Gluten Free Peanut Free Gelatine Free Dairy Free Suitable for Vegetarians ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Alcohol Free Certified Kosher ✔ ✔ U Apple Pie Berry Blue Birthday Cake Blueberry Bubble Gum Buttered Popcorn Item # 36056 Item # 36057 Item # 36058 Item # 36030 Item # 36031 Item # 36032 Cantaloupe (Melon) Cappuccino Caramel Popcorn Cherry Cola Cherry Passion Fruit Smoothie Chocolate Mint Item # 36059 Item # 35815 Item# 36060 Item # 36061 Item # 36062 Item # 36063 Chocolate Pudding Coconut Cotton -

Adams & Brooks Adds Fun & Flavor to Lollipops With

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ADAMS & BROOKS ADDS FUN & FLAVOR TO LOLLIPOPS WITH NEW JELLY BELLY® BEAN SHAPED LOLLIPOPS Unique lollipops use Jelly Belly jelly bean flavors and iconic shape to innovate the category LOS ANGELES, CA., May 23, 2017 - Imagine enjoying your favorite Jelly Belly® jelly bean flavors in a lollipop! Adams & Brooks is pleased to launch a unique, new line of licensed Jelly Belly lollipops made with real Jelly Belly bean flavors in fun bean shapes. The 3-dimensional lollipops are shaped just like the iconic Jelly Belly bean and even have embossed Jelly Belly logos. “We are excited to partner with Jelly Belly on the launch of these new licensed lollipops featuring iconic Jelly Belly jelly bean flavors and the powerful Jelly Belly brand”, says Shelly Clarey, Vice President of Sales and Marketing for Adams & Brooks. “Jelly Belly is known for its delicious, true-to-life flavors. We are using their flavors to ensure that we offer the same intense, gourmet taste experience in our lollipops.” Adams & Brooks will offer collections of Jelly Belly lollipops for everyday as well as key seasons: Halloween, Christmas, Valentine’s Day, Easter and Spring/Summer. Shipping in August 2017, the everyday lollipops will be available in six favorite flavors: Very Cherry, Buttered Popcorn, Green Apple, Berry Blue, Bubble Gum and Grape. “The combination of the Jelly Belly brand and its incredible flavors is an opportunity to add some innovation and excitement to the lollipop category,” said Clarey. “These fun new lollipops are perfect for a sweet treat on the go, parties, gifting and seasonal fun.” The new seasonal lines will mix and match Jelly Belly jelly bean flavors and colors according to the season such as Very Cherry and Green Apple for Christmas and Bubble Gum and Very Cherry for Valentine’s Day. -

Kosher Nosh Guide Summer 2020

k Kosher Nosh Guide Summer 2020 For the latest information check www.isitkosher.uk CONTENTS 5 USING THE PRODUCT LISTINGS 5 EXPLANATION OF KASHRUT SYMBOLS 5 PROBLEMATIC E NUMBERS 6 BISCUITS 6 BREAD 7 CHOCOLATE & SWEET SPREADS 7 CONFECTIONERY 18 CRACKERS, RICE & CORN CAKES 18 CRISPS & SNACKS 20 DESSERTS 21 ENERGY & PROTEIN SNACKS 22 ENERGY DRINKS 23 FRUIT SNACKS 24 HOT CHOCOLATE & MALTED DRINKS 24 ICE CREAM CONES & WAFERS 25 ICE CREAMS, LOLLIES & SORBET 29 MILK SHAKES & MIXES 30 NUTS & SEEDS 31 PEANUT BUTTER & MARMITE 31 POPCORN 31 SNACK BARS 34 SOFT DRINKS 42 SUGAR FREE CONFECTIONERY 43 SYRUPS & TOPPINGS 43 YOGHURT DRINKS 44 YOGHURTS & DAIRY DESSERTS The information in this guide is only applicable to products made for the UK market. All details are correct at the time of going to press but are subject to change. For the latest information check www.isitkosher.uk. Sign up for email alerts and updates on www.kosher.org.uk or join Facebook KLBD Kosher Direct. No assumptions should be made about the kosher status of products not listed, even if others in the range are approved or certified. It is preferable, whenever possible, to buy products made under Rabbinical supervision. WARNING: The designation ‘Parev’ does not guarantee that a product is suitable for those with dairy or lactose intolerance. WARNING: The ‘Nut Free’ symbol is displayed next to a product based on information from manufacturers. The KLBD takes no responsibility for this designation. You are advised to check the allergen information on each product. k GUESS WHAT'S IN YOUR FOOD k USING THE PRODUCT LISTINGS Hi Noshers! PRODUCTS WHICH ARE KLBD CERTIFIED Even in these difficult times, and perhaps now more than ever, Like many kashrut authorities around the world, the KLBD uses the American we need our Nosh! kosher logo system. -

Download and Print the List

Boston Children’s Hospital GI / Nutrition Department 300 Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115 617-355-2127 - CeliacKidsConnection.org This is a list of gluten-free candy by company. Many of your favorite candies may be made by a company you do not associate with that candy. For example, York Peppermint Patties are made by Hershey. If you do not know the parent company, you can often find the name on the product label. In addition, this list is searchable. Open the list in Adobe reader and use the search or magnifying glass icon and search for the name of your favorite candy. Ce De Candy / Smarties Ferrara Candy Co. Continued www.smarties.com • Brach’s Chocolates - Peanut Caramel From the Ce De “Our Candy” Page Clusters, Peanut Clusters, Stars, All Smarties® candy made by Smarties Candy Chocolate Covered Raisins Company is gluten-free and safe for people with • Brach's Double Dipped Peanuts/Double Celiac Disease. Dippers (they are processed in a facility that processes wheat) If the UPC number on the packaging begins with • Brach’s Cinnamon Disks “0 11206”, you can be assured that the product • Brach's Candy Corn - All Varieties is gluten-free, manufactured in a facility that • Brach's Cinnamon Imperials makes exclusively gluten-free products and safe • Brach's Conversation Hearts to eat for people with Celiac Disease. • Brach's Halloween Mellowcremes - All Varieties • Brach's Jelly Bean Nougats Ferrara Candy Company • Brach's Lemon Drops 800-323-1768 • Brach's Wild 'N Fruity Gummi Worms www.ferrarausa.com • Butterfinger (Formerly a Nestle candy) From an email dated 9/15/2020 & 9/18/2020 • Butterfinger bites (Formerly a Nestle Ferrara products contain only Corn Gluten. -

Specialty Catalog

Y E A R R O U N Specialty D Catalog 2019-2020 A U T U M N C H R I S T M A S A little change can do a lot of good. We combined our year-round and Autumn/Christmas products into one comprehensive catalog to carry you into 2020. Discover new and favorite year-round and seasonal offerings. Let the strength of the Jelly Belly brand work for your business. With our range of packaged items, variety of flavors, and selection of licensed candy, there is something for everyone! The fourth, fifth, sixth and seventh generations of our candy family work in the company. contents Bulk 4-7 Organic & Sunkist® 39 Recipe Mix™ 8-9 Sport Beans 40 Bags 10-17 Bigger Bags & Sugar-Free 41 Harry Potter™ 18-20 Autumn 42-43 Star Wars™ & Disney Frozen 21 Christmas 44-47 Gift & Novelty 22-31 Displays 48-50 Gift Bags 32-33 Store Decor 51-56 Boxes 34-38 All Jelly Belly candies are Kosher Certified, unless indicated by * = Universal Kosher Dairy. Jelly Belly® jelly beans are not your ordinary jelly beans. They are smaller, softer and brighter, with true-to-life, mouth-watering flavors in both the center and the shell. We use real ingredients whenever possible. bulk® Jelly Belly Jelly Beans ~ Single Flavors Berry Blue Blueberry Bubble Gum Buttered Popcorn Cantaloupe Cappuccino Caramel Corn Item # 52820 Item # 52989 Item # 52923 Item # 52895 Item # 52948 Item # 52815 Item # 52825 Champagne Chili Mango Chocolate Pudding Cinnamon Coconut Cold Stone® Cold Stone® Mint Mint Item # 52861 Item # 53207 Item # 52807 Item # 52897 Item # 52802 Birthday Cake Chocolate Chocolate Remix™ -

Specialty Catalog 2018 Marks Our Company’S 120Th Year in Business, and We Are Proud to Still Be a Family Owned and Operated Company

28 29 Specialty Catalog 2018 marks our company’s 120th year in business, and we are proud to still be a family owned and operated company. Our company has grown over the years, and our commitment to customer satisfaction with focus on quality and innovation has been at the center of this growth. Inside the 2018/2019 catalog you will see some of our most revolutionary products, right from the original, to new classics, to all-time favorites—a range of products to choose from! Let us help you replenish and expand your Jelly Belly offerings. The fourth, fifth, sixth and seventh generations of our candy family work in the company. Bulk 4-7 Bags 8-17 Harry Potter™ 18-19 Gift Bags 20-21 Gifts & Novelty 22-35 Boxes 36-40 Organic & Sunkist 41 Sport Beans 42 Bigger Bags 43 Displays & Store Decor 44-52 All Jelly Belly candies are Kosher Certified, unless indicated by * = Universal Kosher Dairy. = Non Kosher Item Jelly Belly® jelly beans are not your ordinary jelly beans. They are smaller, softer and brighter, with true-to-life, mouth-watering flavors in both the center and the shell. We use real ingredients whenever possible. Jelly Belly® Jelly Beans ~ Single Flavors Berry Blue Blueberry Bubble Gum Buttered Popcorn Cantaloupe Cappuccino Caramel Corn Item # 52820 Item # 52989 Item # 52923 Item # 52895 Item # 52948 Item # 52815 Item # 52825 NEWB Champagne Chili Mango Chocolate Pudding Cinnamon Coconut Cold Stone Cold Stone Mint Mint Item # 52861 Item # 53207 Item # 52807 Item # 52897 Item # 52802 Birthday Cake Chocolate Chocolate Remix™ • Item # 52853 -

The Effect of Mint Gum and Mint Candy on Memory Recall Morgan Neighbors and Leah Faber Hanover College

The Effect of Mint Gum and Mint Candy on Memory Recall Morgan Neighbors and Leah Faber Hanover College Abstract However, we are only having participants do one of the two, whereas they had We did this to reduce the possibility of having order effects on our results. Each Discussion This study was conducted to examine the effect of chewing gum or sucking participants do both. participant listened to the first set of twenty nouns and then sat in silence for We hypothesized that chewing on a piece of gum would have an effect on on a mint had to memory recall. Participants (N = 39) in our study were asked to We are also having every participant complete a round with nothing in his or sixty seconds while chewing on the gum, sucking on the mint, or having nothing one’s ability to recall the words. When doing prior research, we noticed a various listen to a list of 20 randomized words and recall as many as they could with her mouth. This is so we will be able to measure the impact that gum versus mint in their mouth. amount of different tasks used to measure short-term memory. As a result, we nothing in their mouths. Next, half of our participants (N=20) were asked to will have compared to having nothing. We are having participants listen to a list After the sixty seconds passed, they were instructed to get rid of the mint or concluded that different tasks could be the reasoning behind the varying of chew gum that is mint flavored and the second half of our participants (N=19) of twenty words twice. -

Item and Price List

Candies by Vletas Since 1912 1201 North First Street – In the REA Baggage Depot In the Historical District of Downtown Abilene, Texas 79601 325-673-2005 1-800-725-6933 fax 325-673-6933 Store Hours: Monday-Friday 10am - 5:30pm Saturday 10am – 5pm MILK CHOCOLATE - $6 & $12 (4.16oz & 8.32oz) Almond, Almond Toffee, Brazil Nut, Caramel, Caramel Pecan, Caramel with Sea Salt, Cashew, Cherry Cordial, Chewy Coconut, Chocolate Crème, Coconut Clusters, Coffee Bean, Fairy Food, Graham Crackers, Krispy, Maple Crème, Marshmallow, Milk Chocolate, Nonpareils, Orange Crème, Peanut, Peanut Brittle, Mini Peanut Butter Cups, Peanut Butter Cup, Pecan, Pistachio, Potato Chips, Pretzels, Raisin, Raspberry Crème, Toffee Pretzels, Vanilla Crème, Walnut DARK CHOCOLATE - $6 (4.16oz) Almond, Almond Toffee, Caramel, Caramel Pecan, Caramel with Sea Salt, Cashew, Cherry Cordial, Chewy Coconut, Chocolate Crème, Coconut Clusters, Coffee Beans, Dark Chocolate, Fairy Food, Lemon Crème, Marshmallow, Peanut, Peanut Butter Cups, Pecan, Orange Crème, Orange Peel, Raspberry Crème, Thin Mints, Vanilla Crème, 72% Cocoa WHITE CHOCOLATE - $6 (4.16oz) Almond, Apricot, Cashew, Chewy Coconut, Pecan, Peanut Butter Cups, Peppermint, Pretzel, White Chocolate, White Chocolate Caramel Popcorn SUGAR FREE - $6 (4.16oz) Almond, Almond Toffee, Milk Cherry Cordial, Dark Cherry Cordial, Chocolate Caramel, Caramel Pecan, Cashew, Coconut Cluster, Chewy Coconut, Milk Chocolate, Jelly Beans, Orange Crème, Peanut, Peanut Butter Cup, Pecan, Chocolate Pretzel, Raspberry Crème, Taffy, Vanilla Crème, -

Sector Trend Analysis

MARKET ACCESS SECRETARIAT Global Analysis Report Sector Trend Analysis Sugar Confectionery In Belgium January 2017 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY CONTENTS This report brings together consumer insight and market data to Executive Summary ....................... 1 provide a comprehensive brief of the sugar confectionery sector in Belgium to Canadian exporters. This allows for the rapid Consumer Attitudes and Economic identification of key growth opportunities across major sugar Drivers ............................................ 2 confectionery categories. It also provides market share of the key distribution channels. Finaly, the report includes brand share data Retail Sales .................................... 2 of the Confectionery market in Belgium. New Sugar Confectionery Currently, imports of sugar confectionery into the European Union Products ......................................... 4 (E.U.) face tariffs starting at 6.2%. Canadian sugar confectionery exports will enter the E.U. duty free immediately upon entry into Distribution Channels ..................... 5 force of the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement New Product Examples .................. 8 (CETA). Under CETA, certain exports of Canadian sugar confectionery will also have access to Origin Quotas (which provide Tarrif Schedule ............................. 10 more liberal rules of origin), including an Origin Quota of 10,000 tonnes for Sugar Confectionery and Chocolate Preparations such Conclusion .................................... 10 as bubble gum, sugar candies, and chocolate -

Reading Manual for Mint and Mint Product Processing Under PMFME Scheme

Reading Manual for Mint and Mint Product Processing Under PMFME Scheme National Institute of Food Technology Entrepreneurship and Management Ministry of Food Processing Industries Plot No.97, Sector-56, HSIIDC, Industrial Estate, Kundli, Sonipat, Haryana-131028 Website: http://www.niftem.ac.in Email: [email protected] Call: 0130-2281089 PM FME – Mint and Mint Product Processing CONTENTS No Chapter Section Page No 1 Introduction 2 1.1 Mint description 2 1.2 Local names for mint in India 3 1.3 Common varieties 3-4 1.4 Botanical description 5 1.5 Economic importance 5-6 1.6 Agro-climatic condition requirements 6-8 1.7 Harvesting and yield 8-9 1.8 Post-harvest management 9 2 Processing of mint and mint products 10 2.1 Peppermint (Mentha piperita l.) 10-11 2.2 Storage of mint leaves 12 2.3 Drying of mint 12 2.4 Freezing mint 13 2.5 Mint products 13-16 2.6 Mint oils 16-18 2.7 Menthol from mint oil 18 2.8 Peppermint oil extraction 18-19 2.9 Breathmint 19 2.10 Tableted candies and mints 19-21 3 Machineries for spice processing 22 3.1 Drying 22 3.2 Grinding and pulverizing 22 3.3 Mixing 23 3.4 Sieving 23 3.5 Packaging 23 4 Packaging of mint & mint products 24 Factors to be considered while choosing 4.1 24 packaging material Materials used in packaging of mint and 4.2 24 mint products 4.3 Types of packages 26-33 5 FSSAI regulations 34 5.1 Regulation for Spices 34 5.2 Regulation for dried mint 34-35 5.3 ASTA standards 35-36 5.4 ESA quality minima for spices 36 1 PM FME – Mint and Mint Product Processing CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Spices are high value export-oriented crops extensively used for flavoring food and beverages, medicines, cosmetics, perfumery etc. -

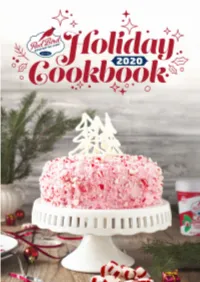

Redbird Holidaycookbook.Pdf

In 1890, we got our start as the NC Candy Company, 3 right in Lexington NC. In the early 1900s, the company About was renamed the Piedmont Candy Company. In 1919, Edward Ebelein, the son of German Immigrants, moved to Lexington to work at the NC Red Bird Candy Company. Edward was born in 1873 and became a candy apprentice at 15. He later became the sole owner of the company and ran it as a family business. Red Bird candies were made using open copper kettles to heat pure cane sugar to 300° F. On average, about 2,000 pounds of candy puffs and sticks were made each day! Red Bird Holiday Cookbook Holiday Bird Red ‘‘Here at the Piedmont Candy Company, we’ve In 1987, the Ebeleins sold the company to another local been making Red Bird puffed mints and candies North Carolina family, the Reids. Doug Reid had spent his career working in textiles but much of that industry from our hometown in Lexington, NC since 1890. was moving overseas. Even today, the Piedmont Candy Using only 100% pure cane sugar, it’s more than a Company is one of the few candy companies with recipe – it’s a family tradition.” production still in the USA. Piedmont Candy Company continued to grow and in 2000 expanded again to help meet demand. While modern production processes were added, the basic process stayed the same. Our candy stripes are still molded and applied by hand making each finished stick or puff a little unique. Red Bird Peppermint Puffs and sticks are still crafted with just a few simple ingredients like pure cane sugar and natural peppermint oil.