Community Perceptions of the Beverly-Qamanirjuaq Caribou Management Board

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Path to Reconciliation Act ______

THE PATH TO RECONCILIATION ACT __________________ ANNUAL PROGRESS REPORT PREPARED BY MANITOBA INDIGENOUS AND NORTHERN RELATIONS DECEMBER 2020 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary: The Path to Reconciliation in Manitoba ....................................................... 3 Background ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 7 Calls to Action: Legacies - New Initiatives....................................................................................... 8 Child Welfare .............................................................................................................................. 8 Education .................................................................................................................................... 9 Language and Culture ............................................................................................................... 11 Health ........................................................................................................................................ 12 Justice ........................................................................................................................................ 14 Calls to Action: Reconciliation - New Initiatives ........................................................................... 16 Canadian -

Aboriginal Organizations and with Manitoba Education, Citizenship and Youth

ABORIGINAL ORGANIZATIONS IN MANITOBA A Directory of Groups and Programs Organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis People 2011/2013 ABORIGINAL ORGANIZATIONS IN MANITOBA A Directory of Groups and Programs Organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Métis People 2011 / 2013 ________________________________________________________________ Compiled and edited by Aboriginal Education Directorate and Aboriginal Friendship Committee Fort Garry United Church Winnipeg, Manitoba Printed by Aboriginal Education Directorate Manitoba Education, Manitoba Advanced Education and Literacy and Aboriginal Affairs Secretariat Manitoba Aboriginal and Northern Affairs INTRODUCTION The directory of Aboriginal organizations is designed as a useful reference and resource book to assist people to locate the appropriate organizations and services. The directory also serves as a means of improving communications among people. The idea for the directory arose from the desire to make information about Aboriginal organizations more available to the public. This directory was first published in 1975 and has grown considerably since its initial edition, which had 16 pages compared to the 100 pages of the present edition. The directory reflects the vitality and diversity of Aboriginal cultural traditions, organizations, and enterprises. The editorial committee has made every effort to present in this directory an accurate and up-to-date listing. Fax numbers, Email addresses and Websites have been included whenever available. Inevitably, errors and omissions will have occurred in the revising and updating of this Directory, and the committee would greatly appreciate receiving information about such oversights, as well as changes and new information to be included in a future revision. Please call, fax or write to the Aboriginal Friendship Committee, Fort Garry United Church, using the information on the next page. -

COVID-19 Community Bulletin #1 Mental Wellness Supports During the COVID-19 Pandemic

COVID-19 Community Bulletin #1 Mental wellness supports during the COVID-19 pandemic Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak (MKO) and Keewatinohk Inniniw Minoayawin Inc. (KIM) are collaborating with Mental Wellness Services in Manitoba to support Northern First Nations’ leadership and Health Directors during the COVID-19 global pandemic. Feelings of distress, anxiety, fear, and grief can heighten as Manitoba communities practice social and physical distancing during this unprecedented health crisis. In response to the need for people to access mental wellness support and service during COVID-19, mental wellness teams and programs have adapted their methods of communication and will respond through virtual means to continue serving those coping with suicide attempts, completed suicides, homicide, multiple deaths, trauma due to violent assault, or other serious events that impact many people. Each Wellness Team is committed to: • Providing confidential mental wellness support with a culturally safe and trauma-informed care approach to all Manitoba First Nations on and off reserve. • Ensuring all services and on-call crisis responses are accessible via telephone or text with various services, including virtual support with FaceTime and/or Zoom video conferencing, where applicable. • Ensuring their mental wellness team members and health care providers are trained to help manage an individual's mental health during COVID-19. • Sharing the most current and accurate information-based facts from provincial and federal public health authorities. • Staying informed of safety measures during COVID-19, as guided by the Province of Manitoba Chief Public Health Officer and public health authorities. COVID-19 Community Bulletin #1 for Leadership & Health Directors – April 7, 2020 Mental Wellness Supports in Manitoba Dakota Ojibway Health Services • Available since 2017, the Dakota Ojibway Tribal Council (DOTC) based in Headingley, provides an on-call crisis response for youth and adults who are in crisis due to mental health concerns, suicide and/or addiction issues. -

2010-2011 Annual Report

First Nations of Northern Manitoba Child and Family Services Authority CONTACT INFORMATION Head Office Box 10460 Opaskwayak, Manitoba R0B 2J0 Telephone: (204) 623-4472 Facsimile: (204) 623-4517 Winnipeg Sub-Office 206-819 Sargent Avenue Winnipeg, Manitoba R3E 0B9 Telephone: (204) 942-1842 Facsimile: (204) 942-1858 Toll Free: 1-866-512-1842 www.northernauthority.ca Thompson Sub-Office and Training Centre 76 Severn Crescent Thompson, Manitoba R8N 1M6 Telephone: (204) 778-3706 Facsimile: (204) 778-3845 7th Annual Report 2010 - 2011 First Nations of Northern Manitoba Child and Family Services Authority—Annual Report 2010-2011 16 First Nations of Northern Manitoba Child and Family Services Authority—Annual Report 2010-2011 FIRST NATION AGENCIES OF NORTHERN MANITOBA ABOUT THE NORTHERN AUTHORITY First Nation leaders negotiated with Canada and Manitoba to overcome delays in implementing the AWASIS AGENCY OF NORTHERN MANITO- Aboriginal Justice Inquiry recommendations for First Nation jurisdiction and control of child welfare. As a result, the First Nations of Northern Manitoba Child and Family Services Authority (Northern BA Authority) was established through the Child and Family Services Authorities Act, proclaimed in November 2003. Cross Lake, Barren Lands, Fox Lake, God’s Lake Narrows, God’s River, Northlands, Oxford House, Sayisi Dene, Shamattawa, Tataskweyak, War Lake & York Factory First Nations Six agencies provide services to 27 First Nation communities and people in the surrounding areas in Northern Manitoba. They are: Awasis Agency of Northern Manitoba, Cree Nation Child and Family Caring Agency, Island Lake First Nations Family Services, Kinosao Sipi Minosowin Agency, CREE NATION CHILD AND FAMILY CARING Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation FCWC and Opaskwayak Cree Nation Child and Family Services. -

Directory – Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba

Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba A directory of groups and programs organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis people Community Development Corporation Manual I 1 INDIGENOUS ORGANIZATIONS IN MANITOBA A Directory of Groups and Programs Organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis People Compiled, edited and printed by Indigenous Inclusion Directorate Manitoba Education and Training and Indigenous Relations Manitoba Indigenous and Municipal Relations ________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION The directory of Indigenous organizations is designed as a useful reference and resource book to help people locate appropriate organizations and services. The directory also serves as a means of improving communications among people. The idea for the directory arose from the desire to make information about Indigenous organizations more available to the public. This directory was first published in 1975 and has grown from 16 pages in the first edition to more than 100 pages in the current edition. The directory reflects the vitality and diversity of Indigenous cultural traditions, organizations, and enterprises. The editorial committee has made every effort to present accurate and up-to-date listings, with fax numbers, email addresses and websites included whenever possible. If you see any errors or omissions, or if you have updated information on any of the programs and services included in this directory, please call, fax or write to the Indigenous Relations, using the contact information on the -

A Roadmap to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Call to Action #66

INDIGENOUS YOUTH VOICES A Roadmap to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Call to Action #66 JUNE 2018 INDIGENOUS YOUTH VOICES 1 Kitinanaskimotin / Qujannamiik / Marcee / Miigwech: To all the Indigenous youth and organizations who took the time to share their ideas, experiences, and perspectives with us. To Assembly of Se7en Generations (A7G) who provided Indigenous Youth Voices Advisors administrative and capacity support. ANDRÉ BEAR GABRIELLE FAYANT To the Elders, mentors, friends and family who MAATALII ANERAQ OKALIK supported us on this journey. To the Indigenous Youth Voices team members who Citation contributed greatly to this Roadmap: Indigenous Youth Voices. (2018). A Roadmap to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Call to Action #66. THEA BELANGER MARISSA MILLS Ottawa, Canada Anishinabe/Maliseet Southern Tuschonne/Michif Electronic ISBN Paper ISBN ERIN DONNELLY NATHALIA PIU OKALIK 9781550146585 9781550146592 Haida Inuk LINDSAY DUPRÉ CHARLOTTE QAMANIQ-MASON WEBSITE INSTAGRAM www.indigenousyouthvoices.com @indigenousyouthvoices Michif Inuk FACEBOOK TWITTER WILL LANDON CAITLIN TOLLEY www.fb.com/indigyouthvoices2 A ROADMAP TO TRC@indigyouthvoice #66 Anishinabe Algonquin ACKNOWLEDGMENT We would like to recognize and honour all of the generations of Indigenous youth who have come before us and especially those, who under extreme duress in the Residential School system, did what they could to preserve their language and culture. The voices of Indigenous youth captured throughout this Roadmap echo generations of Indigenous youth before who have spoken out similarly in hopes of a better future for our peoples. Change has not yet happened. We offer this Roadmap to once again, clearly and explicitly show that Indigenous youth are the experts of our own lives, capable of voicing our concerns, understanding our needs and leading change. -

Regional Stakeholders in Resource Development Or Protection of Human Health

REGIONAL STAKEHOLDERS IN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT OR PROTECTION OF HUMAN HEALTH In this section: First Nations and First Nations Organizations ...................................................... 1 Tribal Council Environmental Health Officers (EHO’s) ......................................... 8 Government Agencies with Roles in Human Health .......................................... 10 Health Canada Environmental Health Officers – Manitoba Region .................... 14 Manitoba Government Departments and Branches .......................................... 16 Industrial Permits and Licensing ........................................................................ 16 Active Large Industrial and Commercial Companies by Sector........................... 23 Agricultural Organizations ................................................................................ 31 Workplace Safety .............................................................................................. 39 Governmental and Non-Governmental Environmental Organizations ............... 41 First Nations and First Nations Organizations 1 | P a g e REGIONAL STAKEHOLDERS FIRST NATIONS AND FIRST NATIONS ORGANIZATIONS Berens River First Nation Box 343, Berens River, MB R0B 0A0 Phone: 204-382-2265 Birdtail Sioux First Nation Box 131, Beulah, MB R0H 0B0 Phone: 204-568-4545 Black River First Nation Box 220, O’Hanley, MB R0E 1K0 Phone: 204-367-8089 Bloodvein First Nation General Delivery, Bloodvein, MB R0C 0J0 Phone: 204-395-2161 Brochet (Barrens Land) First Nation General Delivery, -

Mennonite Institutions

-being the Magazine/Journal of the Hanover Steinbach Historical Society Inc. Preservings $10.00 No. 18, June, 2001 “A people who have not the pride to record their own history will not long have the virtues to make their history worth recording; and no people who are indifferent to their past need hope to make their future great.” — Jan Gleysteen Mennonite Institutions The Mennonite people have always been richly Friesen (1782-1849), Ohrloff, Aeltester Heinrich portant essay on the historical and cultural origins endowed with gifted thinkers and writers. The Wiens (1800-72), Gnadenheim, and theologian of Mennonite institutions. The personal reflections seminal leaders in Reformation-times compiled Heinrich Balzer (1800-42) of Tiege, Molotschna, of Ted Friesen, Altona, who worked closely with treatises, polemics and learned discourses while continued in their footsteps, leaving a rich literary Francis during his decade long study, add a per- the martyrs wrote hymns, poetic elegies and in- corpus. sonal perspective to this important contribution to spirational epistles. During the second half of the The tradition was brought along to Manitoba the Mennonite people. The B. J. Hamm housebarn in the village of Neu-Bergthal, four miles southeast of Altona, West Reserve, Manitoba, as reproduced on the cover of the second edition of E. K. Francis, In Search of Utopia, republished by Crossway Publications Inc., Box 1960, Steinbach, Manitoba, R0A 2A0. The house was built in 1891 by Bernhard Klippenstein (1836-1910), village Schulze, and the barn dates to the founding of the village in 1879, and perhaps even earlier to the village of Bergthal in the East Reserve. -

Community Liaison Program: Bridging Land-Use Perspectives of First Nation Communities and the Minerals Resource Sector in Manitoba by L.A

GS-19 Community liaison program: bridging land-use perspectives of First Nation communities and the minerals resource sector in Manitoba by L.A. Murphy Murphy, L.A. 2011: Community liaison program: bridging land-use perspectives of First Nation communities and the minerals resource sector in Manitoba; in Report of Activities 2011, Manitoba Innovation, Energy and Mines, Manitoba Geological Survey, p. 180–181. Summary Model Forest Junior Rangers The Manitoba Geological Survey (MGS) community program, Nopiming Provincial liaison program provides a geological contact person Park on the east side of Lake for Manitoba First Nation communities and the Winnipeg (Figure GS-19-1) minerals resource sector. The mandate for this program Red Sucker Lake First Nation in the Island Lake acknowledges and respects the First Nation land-use traditional land-use area perspective, allows for an open exchange of mineral Bunibonibee Cree Nation in the Oxford House information, and encourages the integration of geology traditional land-use area and mineral-resource potential into the land-use planning Sapotaweyak First Nation Community Interest Zone process. Timely information exchange is critical to all Gods Lake First Nation in Gods Lake Narrows stakeholders, and open communication of all concerns Tataskweyak Cree Nation in Split Lake regarding multiple land-use issues reduces timelines and mitigates potential impacts to Aboriginal and Treaty rights. Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak Inc. (MKO) Schools, communities and mineral industry stakeholders representing Manitoba’s northern First Nations and throughout Manitoba access the program during land-use Tribal councils planning processes, encouraging a balanced approach to College Pierre-Elliot-Trudeau, Transcona School economic development in traditional land-use areas. -

Sayisi Dene Mapping Initiative, Tadoule Lake Area, Manitoba (Part of NTS 64J9, 10, 15, 16) by L.A

GS-15 Sayisi Dene Mapping Initiative, Tadoule Lake area, Manitoba (part of NTS 64J9, 10, 15, 16) by L.A. Murphy and A.R. Carlson Murphy, L.A. and Carlson, A.R. 2009: Sayisi Dene Mapping Initiative, Tadoule Lake area, Manitoba (part of NTS 64J9, 10, 15, 16); in Report of Activities 2009, Manitoba Innovation, Energy and Mines, Manitoba Geological Survey, p. 154–159. Summary metasedimentary units and rafts In the summer of 2009, the Manitoba Geological Sur- of possible Archean provenance. vey (MGS) conducted the first half of a four-week geo- Petrology, geochemistry and Sm- logical mapping course with the Sayisi Dene First Nation Nd isotope analyses of samples at Tadoule Lake, Manitoba. The goals of the program are collected in the Tadoule Lake area will provide constraints to help increase awareness of the region’s geology and necessary to determine the nature, ages and contact rela- mineral resources, provide the basic skills needed to work tionships of exposed rock types. This work may help in a mineral-exploration camp and foster information- interpret geological domain boundaries in the Tadoule sharing between First Nation communities and the MGS. Lake area in conjunction with other projects that are all Four members of the community were hired as student- part of the ongoing Manitoba Far North Geomapping Ini- trainees and three completed the first half of the program. tiative (Anderson, et al., GS-13, this volume). One of the trainees was hired by the MGS as a field assis- tant to geologists working in the Seal River–Great Island Introduction area between Tadoule Lake and Churchill. -

Annual General Report 2019

Annual General Report 2019 Restoring Inherent Jurisdiction Advocating for MKO Nations to assert authority over our lands, children and culture Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak Inc. Table of Contents Acronyms ........................................................................................................ 3 Grand Chief’s Message .................................................................................. 4 Department Reports for the 2018-2019 Fiscal Year ....................... 7 Grand Chief’s Office and Funding ............................................................................ 8 Child and Family Services Liaison Unit .......................................................................... 10 Client Navigator .......................................................................................................... 11 Clinical Care Transformation (Health) ............................................................................ 13 Communications .......................................................................................................... 14 Economic Development ........................................................................................... 15 Education ......................................................................................................................... 16 First Nations Justice Strategy: Restorative Justice .............................................. 17 Indigenous Skills and Employment Training Program .............................................. 19 Mental Wellness -

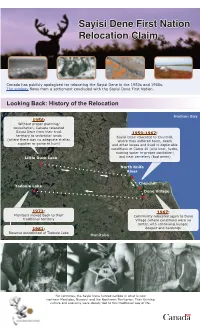

Sayisi Dene First Nation Relocation Claim

Sayisi Dene First Nation Relocation Claim Canada has publicly apologized for relocating the Sayisi Dene in the 1950s and 1960s. The apology flows from a settlement concluded with the Sayisi Dene First Nation. Looking Back: History of the Relocation Hudson Bay 1956: Without proper planning/ consultation, Canada relocated Sayisi Dene from their trad. 1959-1967: territory to unfamiliar lands Sayisi Dene relocated to Churchill, (where there was no adequate shelter, where they suffered harm, death supplies or game to hunt) and other losses and lived in deplorable conditions at Camp 10 (w/o heat, hydro, running water or proper sanitation) Little Duck Lake and near cemetery (bad omen) North Knife River Churchill Tadoule Lake Dene Village 1973: 1967: Members moved back to their Community relocated again to Dene traditional territory Village (where conditions were no better, with continuing hunger, 1981: despair and hardship) Reserve established at Tadoule Lake Manitoba For centuries, the Sayisi Dene hunted caribou in what is now northern Manitoba, Nunavut and the Northwest Territories. Their thriving culture and economy were closely tied to this traditional way of life. Just the Facts: the Relocation Claim Settlement Agreement 816 97% Sayisi Dene members of First Nation members (313 on reserve who voted approved and 503 off reserve) the settlement Settlement includes: $33.6 million from Canada (paid into a Trust for benefit of current/future generations) 13,000 acres of prov. Crown land to be added to First Nation’s reserve Timeline: Resolution process between Canada and Sayisi Dene Sayisi Dene have long sought a resolution, filing their relocation claim with Canada in 1999.