A High Binary Fraction for the Most Massive Close-In Giant Planets and Brown Dwarf Desert Members

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lurking in the Shadows: Wide-Separation Gas Giants As Tracers of Planet Formation

Lurking in the Shadows: Wide-Separation Gas Giants as Tracers of Planet Formation Thesis by Marta Levesque Bryan In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Pasadena, California 2018 Defended May 1, 2018 ii © 2018 Marta Levesque Bryan ORCID: [0000-0002-6076-5967] All rights reserved iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost I would like to thank Heather Knutson, who I had the great privilege of working with as my thesis advisor. Her encouragement, guidance, and perspective helped me navigate many a challenging problem, and my conversations with her were a consistent source of positivity and learning throughout my time at Caltech. I leave graduate school a better scientist and person for having her as a role model. Heather fostered a wonderfully positive and supportive environment for her students, giving us the space to explore and grow - I could not have asked for a better advisor or research experience. I would also like to thank Konstantin Batygin for enthusiastic and illuminating discussions that always left me more excited to explore the result at hand. Thank you as well to Dimitri Mawet for providing both expertise and contagious optimism for some of my latest direct imaging endeavors. Thank you to the rest of my thesis committee, namely Geoff Blake, Evan Kirby, and Chuck Steidel for their support, helpful conversations, and insightful questions. I am grateful to have had the opportunity to collaborate with Brendan Bowler. His talk at Caltech my second year of graduate school introduced me to an unexpected population of massive wide-separation planetary-mass companions, and lead to a long-running collaboration from which several of my thesis projects were born. -

Spiral Arms in Disks: Planets Or Gravitational Instability?

Spiral Arms in Disks: Planets or Gravitational Instability? Item Type Article Authors Dong, Ruobing; Najita, Joan R.; Brittain, Sean Citation Ruobing Dong et al 2018 ApJ 862 103 DOI 10.3847/1538-4357/aaccfc Publisher IOP PUBLISHING LTD Journal ASTROPHYSICAL JOURNAL Rights © 2018. The American Astronomical Society. Download date 27/09/2021 14:50:30 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Version Final published version Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/631109 The Astrophysical Journal, 862:103 (19pp), 2018 August 1 https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/aaccfc © 2018. The American Astronomical Society. Spiral Arms in Disks: Planets or Gravitational Instability? Ruobing Dong (董若冰)1,2 , Joan R. Najita3, and Sean Brittain3,4 1 Department of Physics & Astronomy, University of Victoria, Victoria BC V8P 1A1, Canada 2 Steward Observatory, University of Arizona, 933 North Cherry Avenue, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA; [email protected] 3 National Optical Astronomical Observatory, 950 North Cherry Avenue, Tucson, AZ 85719, USA; [email protected] 4 Department of Physics & Astronomy, 118 Kinard Laboratory, Clemson University, Clemson, SC 29634-0978, USA; [email protected] Received 2018 May 8; revised 2018 June 2; accepted 2018 June 13; published 2018 July 27 Abstract Spiral arm structures seen in scattered-light observations of protoplanetary disks can potentially serve as signposts of planetary companions. They can also lend unique insights into disk masses, which are critical in setting the mass budget for planet formation but are difficult to determine directly. A surprisingly high fraction of disks that have been well studied in scattered light have spiral arms of some kind (8/29), as do a high fraction (6/11) of well- studied Herbig intermediate-mass stars (i.e., Herbig stars >1.5 Me). -

Where Are the Distant Worlds? Star Maps

W here Are the Distant Worlds? Star Maps Abo ut the Activity Whe re are the distant worlds in the night sky? Use a star map to find constellations and to identify stars with extrasolar planets. (Northern Hemisphere only, naked eye) Topics Covered • How to find Constellations • Where we have found planets around other stars Participants Adults, teens, families with children 8 years and up If a school/youth group, 10 years and older 1 to 4 participants per map Materials Needed Location and Timing • Current month's Star Map for the Use this activity at a star party on a public (included) dark, clear night. Timing depends only • At least one set Planetary on how long you want to observe. Postcards with Key (included) • A small (red) flashlight • (Optional) Print list of Visible Stars with Planets (included) Included in This Packet Page Detailed Activity Description 2 Helpful Hints 4 Background Information 5 Planetary Postcards 7 Key Planetary Postcards 9 Star Maps 20 Visible Stars With Planets 33 © 2008 Astronomical Society of the Pacific www.astrosociety.org Copies for educational purposes are permitted. Additional astronomy activities can be found here: http://nightsky.jpl.nasa.gov Detailed Activity Description Leader’s Role Participants’ Roles (Anticipated) Introduction: To Ask: Who has heard that scientists have found planets around stars other than our own Sun? How many of these stars might you think have been found? Anyone ever see a star that has planets around it? (our own Sun, some may know of other stars) We can’t see the planets around other stars, but we can see the star. -

The Denver Observer June 2016

The Denver JUNE 2016 OBSERVER Mercury transits the Sun on May 9, 2016. The planet, seen at the lower left of the Sun's face, has a diameter of about 3,000 miles, but the Sun's 870,000 mile cross-section dwarfs the planet—even though the Sun is seen here at twice Mercury's distance from us. (Note the planet-sized sunspots above-left of solar center.) Image © Ron Pearson. JUNE SKIES by Zachary Singer The Solar System the Martian surface reveals itself. On observing runs over the last few If you haven’t been observing Mars, the “unusually bright orange weeks, with good seeing, early views did indeed yield so-so results, but object in Libra,” now is a really good time: As June begins, the plan- improved noticeably as the planet neared its highest point in the south. et is just past opposition, and even more recently past its closest ap- I was able to make out the Syrtis Major region easily, even though proach to Earth, when the planet’s disk spanned a full 18.6 arcseconds. moonlight was a factor in the initial sessions. It looms large in a telescope now, and even instruments of moderate One great tool for power bring satisfying images at 100 or 150X. By midmonth, Mars improving your view Sky Calendar will be highest around 11 PM, with the disk slightly smaller, at 17.9”; is a “Moon filter.” 4 New Moon by June 30th, though, the planet will have already crossed the Meridian By bringing the sheer 12 First-Quarter Moon at 10 PM, before the sky brightness of Mars’ mag- 20 Full Moon In the Observer is fully dark, and the disk nitude -2 disk down a 27 Last-Quarter Moon will have shrunk some- notch, the moon filter President’s Message . -

Naming the Extrasolar Planets

Naming the extrasolar planets W. Lyra Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69177, Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract and OGLE-TR-182 b, which does not help educators convey the message that these planets are quite similar to Jupiter. Extrasolar planets are not named and are referred to only In stark contrast, the sentence“planet Apollo is a gas giant by their assigned scientific designation. The reason given like Jupiter” is heavily - yet invisibly - coated with Coper- by the IAU to not name the planets is that it is consid- nicanism. ered impractical as planets are expected to be common. I One reason given by the IAU for not considering naming advance some reasons as to why this logic is flawed, and sug- the extrasolar planets is that it is a task deemed impractical. gest names for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known One source is quoted as having said “if planets are found to as of Oct 2009. The names follow a scheme of association occur very frequently in the Universe, a system of individual with the constellation that the host star pertains to, and names for planets might well rapidly be found equally im- therefore are mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology. practicable as it is for stars, as planet discoveries progress.” Other mythologies may also be used given that a suitable 1. This leads to a second argument. It is indeed impractical association is established. to name all stars. But some stars are named nonetheless. In fact, all other classes of astronomical bodies are named. -

Spring Constellations Leo

Night Sky 101: Spring Constellations Leo Leo, the lion, is very recognizable by the head of the lion, which looks like a backwards question mark, and is commonly known as “the sickle.” Regulus, Leo’s brightest star, is also easy to pick out in most lights. The constellation is best seen in April and May, but rises after the Spring Equinox in March. Within the constellation, there are several spiral galaxies: M65, M66, M95, and M96. It is possible to fit M65 and M66 into the same view on a low powered telescope. In Greek mythology, Leo was the Nemean lion, who was completely impervious to bronze, steel and any kind of metal. As part of his 12 labors, Hercules was charged to fight the lion and killed him Photo Credit: Starry Night by strangling him. Hercules took the lion’s pelt as a prize and Leo, the lion, was placed in the stars to commemorate their fight. Virgo Virgo is best seen in the late spring and early summer, usually May to June. The bright star Arcturus, in the constellation Boötes, lines up with the Virgo’s brightest star Spica, which makes it easy to find. Within the constellation is the Virgo Galaxy Cluster, which is a conglomerate of thousands of unnamed galaxies. These galaxies are about 65 million light years away, and usually only appear as smudges in a telescope. Virgo, the maiden, is also known as Persephone, or the daughter of the Demeter. Hades, god of the Un- derworld, fell in love with Virgo and took her to the Underworld. -

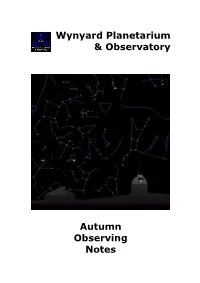

Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory a Autumn Observing Notes

Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory A Autumn Observing Notes Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory PUBLIC OBSERVING – Autumn Tour of the Sky with the Naked Eye CASSIOPEIA Look for the ‘W’ 4 shape 3 Polaris URSA MINOR Notice how the constellations swing around Polaris during the night Pherkad Kochab Is Kochab orange compared 2 to Polaris? Pointers Is Dubhe Dubhe yellowish compared to Merak? 1 Merak THE PLOUGH Figure 1: Sketch of the northern sky in autumn. © Rob Peeling, CaDAS, 2007 version 1.2 Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory PUBLIC OBSERVING – Autumn North 1. On leaving the planetarium, turn around and look northwards over the roof of the building. Close to the horizon is a group of stars like the outline of a saucepan with the handle stretching to your left. This is the Plough (also called the Big Dipper) and is part of the constellation Ursa Major, the Great Bear. The two right-hand stars are called the Pointers. Can you tell that the higher of the two, Dubhe is slightly yellowish compared to the lower, Merak? Check with binoculars. Not all stars are white. The colour shows that Dubhe is cooler than Merak in the same way that red-hot is cooler than white- hot. 2. Use the Pointers to guide you upwards to the next bright star. This is Polaris, the Pole (or North) Star. Note that it is not the brightest star in the sky, a common misconception. Below and to the left are two prominent but fainter stars. These are Kochab and Pherkad, the Guardians of the Pole. Look carefully and you will notice that Kochab is slightly orange when compared to Polaris. -

The Gemini NICI Planet-Finding Campaign: the Frequency of Giant

The Gemini NICI Planet-Finding Campaign: The Frequency of Giant Planets around Young B and A Stars Eric L. Nielsen,1 Michael C. Liu,1 Zahed Wahhaj,2 Beth A. Biller,3 Thomas L. Hayward,4 Laird M. Close,5 Jared R. Males,6 Andrew J. Skemer,7 Mark Chun,1 Christ Ftaclas,1 Silvia H. P. Alencar,6 Pawel Artymowicz,7 Alan Boss,8 Fraser Clarke,9 Elisabete de Gouveia Dal Pino,10 Jane Gregorio-Hetem,10 Markus Hartung,4 Shigeru Ida,11 Marc Kuchner,12 Douglas N. C. Lin,13 I. Neill Reid,14 Evgenya L. Shkolnik,15 Matthias Tecza,9 Niranjan Thatte,9 Douglas W. Toomey16 ABSTRACT We have carried out high contrast imaging of 70 young, nearby B and A stars to search for brown dwarf and planetary companions as part of the Gemini NICI Planet- Finding Campaign. Our survey represents the largest, deepest survey for planets around high-mass stars (≈1.5–2.5 M⊙) conducted to date and includes the planet hosts β Pic and Fomalhaut. We obtained follow-up astrometry of all candidate companions within 400 AU projected separation for stars in uncrowded fields and identified new low-mass 1Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawaii, 2680 Woodlawn Drive, Honolulu HI 96822, USA 2European Southern Observatory, Alonso de C´ordova 3107, Vitacura, Santiago, Chile 3Max-Planck-Institut f¨ur Astronomie, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69117 Heidelberg, Germany 4Gemini Observatory, Southern Operations Center, c/o AURA, Casilla 603, La Serena, Chile 5Steward Observatory, University of Arizona, 933 North Cherry Avenue, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA 6Departamento de Fisica - ICEx - Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Av. -

Jjmonl 1603.Pmd

alactic Observer GJohn J. McCarthy Observatory Volume 9, No. 3 March 2016 GRAIL - On the Trail of the Moon's Missing Mass GRAIL (Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory) was a NASA scientific mission in 2011/12 to map the surface of the moon and collect data on gravitational anomalies. The image here is an artist's impres- sion of the twin satellites (Ebb and Flow) orbiting in tandem above a gravitational image of the moon. See inside, page 4 for information on gravitational anomalies (mascons) or visit http://solarsystem. nasa.gov/grail. The John J. McCarthy Observatory Galactic Observer New Milford High School Editorial Committee 388 Danbury Road Managing Editor New Milford, CT 06776 Bill Cloutier Phone/Voice: (860) 210-4117 Production & Design Phone/Fax: (860) 354-1595 www.mccarthyobservatory.org Allan Ostergren Website Development JJMO Staff Marc Polansky It is through their efforts that the McCarthy Observatory Technical Support has established itself as a significant educational and Bob Lambert recreational resource within the western Connecticut Dr. Parker Moreland community. Steve Barone Jim Johnstone Colin Campbell Carly KleinStern Dennis Cartolano Bob Lambert Mike Chiarella Roger Moore Route Jeff Chodak Parker Moreland, PhD Bill Cloutier Allan Ostergren Cecilia Dietrich Marc Polansky Dirk Feather Joe Privitera Randy Fender Monty Robson Randy Finden Don Ross John Gebauer Gene Schilling Elaine Green Katie Shusdock Tina Hartzell Paul Woodell Tom Heydenburg Amy Ziffer In This Issue "OUT THE WINDOW ON YOUR LEFT" ............................... 4 SUNRISE AND SUNSET ...................................................... 13 MARE HUMBOLDTIANIUM AND THE NORTHEAST LIMB ......... 5 JUPITER AND ITS MOONS ................................................. 13 ONE YEAR IN SPACE ....................................................... 6 TRANSIT OF JUPITER'S RED SPOT .................................... -

2014-08 AUG.Pdf

August First Light Newsletter 1 message August, 2014 Issue 122 AlachuaAstronomyClub.org North Central Florida's Amateur Astronomy Club Serving Alachua County since 1987 BREAKING NEWS -- ROSETTA HAS JUST ARRIVED AT COMET 67/P Member Member Astronomical League Initiated in late 1993 by Europe and the USA, and launched in 2004, the International Rosetta Mission is an historic first: Send a spacecraft to chase and orbit a comet, ride along as the comet plunges sun ward to learn how a frozen comet transforms by the Sun's warmth, and dispatch a controlled lander to make in situ measurements and make first images Member from a comet's surface. NASA Night Sky Network Ten years later Rosetta has now arrived at Comet 67P/Churyumov- Gerasimenko and just successfully made orbit today, 2014 August 6! Unfortunately, global events have foreshadowed this memorable event and news media have largely ignored this impressive space mission. AAC Member photo: The Rosetta comet mission may be the beginning of a story that will tell more about us -- both about our origins and evolution. (Hence, its name "rosetta" for the black basalt stone with inscriptions giving the first clues to deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphics.) Pictures received over past weeks are remarkable with the latest in the past 24 hours showing awesome and incredible detail including views that show the comet is a connected binary object rotating as a unit in 12 hours. Anyone see the glorious pairing of Venus and Jupiter this morning (2016 Aug. 18)? For images see http://www.esa.int/ spaceinimages/Missions/ Except when Mars is occasionally brighter Rosetta than Jupiter, these two planets are the brightest nighttime sky objects (discounting Example Image (Aug. -

Dynamical Stability and Habitability of a Terrestrial Planet in HD74156

A dynamic search for potential habitable planets amongst the extrasolar planets 1,2 1 1 1,3 1, 4 P. Hinds , A. Munro , S. T. Maddison , C. Tan , and M. C. Gino [1] Swinburne University, Australia [2] Pierce College, USA [3] Methodist Ladies’ College, Australia [4] Dudley Observatory, USA ABSTRACT: While the detection of habitable terrestrial planets around nearby stars is currently beyond our observational capabilities, dynamical studies can help us locate potential candidates. Following from the work of Menou & Tabachnik (2003), we use a symplectic integrator to search for potential stable terrestrial planetary orbits in the habitable zones of known extrasolar planetary systems. A swarm of massless test particles is initially used to identify stability zones, and then an Earth-mass planet is placed within these zones to investigate their dynamical stability. We investigate 22 new systems discovered since the work of Menou & Tabachnik, as well as simulate some of the previous 85 extrasolar systems whose orbital parameters have been more precisely constrained. In particular, we model three systems that are now confirmed or potential double planetary systems: HD169830, HD160691 and eps Eridani. The results of these dynamical studies can be used as a potential target list for the Terrestrial Planet Finder. Introduction Numerical Technique Results & Discussion To date 122 extrasolar planets have been detected around 107 stars, with 13 of them To follow the evolution of the planetary systems, we use the SWIFT integration software package1. This The systems we have investigated broadly fall in four categories: (1) unstable being multiple planet systems (Schneider, 2004). Observational evidence for the allows us to model a planetary system and a swarm of massless test particles in orbit around a central star. -

Kein Folientitel

The Doppler Method, or the Radial Velocity Detection of Planets: II. Results Telescope Instrument Wavelength Reference 1-m MJUO Hercules Th-Ar / Iodine cell 1.2-m Euler Telescope CORALIE Th-Ar 1.8-m BOAO BOES Iodine Cell 1.88-m Okayama Obs, HIDES Iodine Cell 1.88-m OHP SOPHIE Th-Ar 2-m TLS Coude Echelle Iodine Cell 2.2m ESO/MPI La Silla FEROS Th-Ar 2.7m McDonald Obs. 2dcoude Iodine cell 3-m Lick Observatory Hamilton Echelle Iodine cell 3.8-m TNG SARG Iodine Cell 3.9-m AAT UCLES Iodine cell 3.6-m ESO La Silla HARPS Th-Ar 8.2-m Subaru Telescope HDS Iodine Cell 8.2-m VLT UVES Iodine cell 9-m Hobby-Eberly HRS Iodine cell 10-m Keck HiRes Iodine cell Campbell & Walker: The Pioneers of RV Planet Searches 1988: 1980-1992 searched for planets around 26 solar-type stars. Even though they found evidence for planets, they were not 100% convinced. If they had looked at 100 stars they certainly would have found convincing evidence for exoplanets. Campbell, Walker, & Yang 1988 „Probable third body variation of 25 m s–1, 2.7 year period, superposed on a large velocity gradient“ The first (?) extrasolar planet around a normal star: HD 114762 with M sin i = 11 MJ discovered by Latham et al. (1989) Filled circles are data taken at McDonald Observatory using the telluric lines at 6300 Ang. The mass was uncomfortably high (remember sin i effect) to regard it unambiguously as an extrasolar planet The Search For Extrasolar Planets At McDonald Observatory Bill Cochran & Artie Hatzes Hobby-Eberly 9 m Telescope Harlan J.