A Restoration Plan for the Coonamessett River

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Nov Warrant Booklet

TOWN OF FALMOUTH MASSACHUSETTS ARTICLES OF THE WARRANT FOR THE NOVEMBER TOWN MEETING WITH RECOMMENDATIONS FROM THE BOARD OF SELECTMEN · FINANCE COMMITTEE · PLANNING BOARD · COMMUNITY PRESERVATION COMMITTEE · PUBLISHED BY THE FINANCE COMMITTEE FOR THE CONVENIENCE OF THE VOTERS 201 AT 7:00 P.M. TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 13, 8 LAWRENCE SCHOOL MEMORIAL AUDITORIUM BOARD OF SELECTMEN Susan L. Moran, Chairman Megan English Braga, Vice Chairman Doug Jones Samuel H. Patterson Douglas C. Brown FALMOUTH FINANCE COMMITTEE Keith Schwegel, Chairman Nicholas S. Lowell, Vice Chairman Susan P. Smith, Secretary Kathleen Beriau, Joseph L. Drolette, Ron Dyer, Peter Hargraves, Mary Harris, Judith P. Magnani, Deborah D. Maguire, James Marnell, Wendy Vogel FALMOUTH PLANNING BOARD Jim Fox, Chairman Patricia H. Kerfoot, Vice Chairman Paul Dreyer, Clerk/Secretary Robert Leary, John Druley, Pamela Harting-Barrat and Charlotte Harris COMMUNITY PRESERVATION COMMITTEE Russell Robbins, Chairman Sandra Cuny, Vice Chairman Paul Glynn, Financial Officer Holly Wilson, Clerk Robert Brown, John Druley, Nicole Goldman, and Steve Patton TOWN MANAGER Julian M. Suso ASSISTANT TOWN MANAGER Peter Johnson-Staub TOWN CLERK Michael Palmer DIRECTOR OF FINANCE Jennifer Petit TOWN COUNSEL Frank K. Duffy TOWN MODERATOR David T. Vieira TOWN MEETING RULES AND PROCEDURES COMMITTEE David T. Vieira, Chairman Gary Anderson, Sandra Cuny, Adrian C.J. Dufresne, Judy Fenwick, Brian Keefe, Sheryl Kozens-Long, Nicholas S. Lowell, Joseph Netto, Michael Palmer, Jeffrey W. Oppenheim and Daniel Shearer 1 “CITIZEN’S CHECK LIST” (Written by North Attleboro) To be considered on each vote: 1. IS IT NECESSARY? Or is it something that is not really needed or perhaps already being provided by a private group? 2. -

A Survey of Anadromous Fish Passage in Coastal Massachusetts

Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries Technical Report TR-16 A Survey of Anadromous Fish Passage in Coastal Massachusetts Part 2. Cape Cod and the Islands K. E. Reback, P. D. Brady, K. D. McLaughlin, and C. G. Milliken Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries Department of Fish and Game Executive Office of Environmental Affairs Commonwealth of Massachusetts Technical Report Technical May 2004 Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries Technical Report TR-16 A Survey of Anadromous Fish Passage in Coastal Massachusetts Part 2. Cape Cod and the Islands Kenneth E. Reback, Phillips D. Brady, Katherine D. McLauglin, and Cheryl G. Milliken Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries Southshore Field Station 50A Portside Drive Pocasset, MA May 2004 Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries Paul Diodati, Director Department of Fish and Game Dave Peters, Commissioner Executive Office of Environmental Affairs Ellen Roy-Herztfelder, Secretary Commonwealth of Massachusetts Mitt Romney, Governor TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 2: Cape Cod and the Islands Acknowledgements . iii Abstract . iv Introduction . 1 Materials and Methods . 1 Life Histories . 2 Management . 4 Cape Cod Watersheds . 6 Map of Towns and Streams . 6 Stream Survey . 8 Cape Cod Recommendations . 106 Martha’s Vineyard Watersheds . 107 Map of Towns and Streams . 107 Stream Survey . 108 Martha’s Vineyard Recommendations . 125 Nantucket Watersheds . 126 Map of Streams . 126 Stream Survey . 127 Nantucket Recommendations . 132 General Recommendations . 133 Alphabetical Index of Streams . 134 Alphabetical Index of Towns . .. 136 Appendix 1: List of Anadromous Species in MA . 138 Appendix 2: State River Herring Regulations . 139 Appendix 3: Fishway Designs and Examples . 140 Appendix 4: Abbreviations Used . 148 ii Acknowledgements The authors wish to thank the following people for their assistance in carrying out this survey and for sharing their knowledge of the anadromous fish resources of the Commonwealth: Brian Creedon, Tracy Curley, Jack Dixon, George Funnell, Steve Kennedy, Paul Montague, Don St. -

E. Fisheries and Wildlife

E. Fisheries and Wildlife Until recent decades, the vast majority of Mashpee’s territory was the domain not of man, but of beast. Our woods were only occasionally broken by a roadway, or a few homes, or a farmer’s fields. The hunting was good. Our clear lakes were famous for their fishing. Our streams flowed clean to pristine coastal bays teeming with fish and shellfish that helped feed and support many families. Much has changed with the explosive development of the last fifty years, and much of our wildlife has disappeared along with the natural habitat that supported it. However, much remains for our enjoyment and safekeeping. In this section we will look at Mashpee’s fish and shellfish, its mammals, birds and insects, important wildlife movement corridors and those species living in our town which are among the last of their kind. 1. Finfish Mashpee hosts four types of fin fisheries: fresh water ponds, rivers and streams, estuaries and coastal ponds and the open ocean. Our four large ponds provide some of the best fishing in the state. 203-acre Ashumet Pond, 317- acre Johns Pond and 729-acre Mashpee-Wakeby Pond are all cold water fisheries stocked with brown, brook and rainbow trout. In the last century, such famous anglers as Daniel Webster, President Grover Cleveland and the famous actor Joseph Jefferson looked forward to their fishing expeditions to Mashpee, while local residents looked forward to the income provided serving as guides to those and other wealthy gentlemen. Ashumet and Johns Ponds are also noted for their smallmouth bass, while Mashpee-Wakeby provides not only the smallmouth, but also chain pickerel, white perch and yellow perch. -

DMF Sets New Course by Paul Diodati, Director Time Flies and It’S Been a Year Since Taking Over the Helm at DMF

Published quarterly by the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries to inform and educate its constituents on matters relating to DMF the conservation and sustainable use of the Commonwealth's marine resources NEWS Volume 21 First Quarter January - March 2001 DMF Sets New Course by Paul Diodati, Director Time flies and it’s been a year since taking over the helm at DMF. The challenges of the past year have been met, and I am pleased that the public can again access our senior staff, and licensing program at the new Boston office. Staff have worked diligently to complete the new commercial licensing system that brings DMF into the 21st century. Fishermen and seafood dealers have overwhelmingly supported this new format. DMF has not undergone restructuring for over 30 years. While the cliché, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it,” may hold true in many instances, it does not apply very well to administra- tion of government agencies. Periodic evaluations and strategic changes are critical to overall effectiveness and contribute to longevity of professional organizations. For this reason I’ve devoted much of my first year as DMF’s Director to an examination of our functions, services we provide, and our available resources relative to the agency’s mission with reorganization in mind. A new organizational structure for the Division has been and protect the living marine resources, environment, and completed. It will be highlighted at DMF’s homepage after it fisheries that comprise it. The ex-vessel value of commer- is presented to our staff in April. Restructuring to make better cially-caught fish and direct expenditures related to recre- use of existing resources have forced me to make some ational saltwater fishing exceed a half billion dollars per year. -

321 CMR: DIVISION of FISHERIES and WILDLIFE 321 CMR 4.00: FISHING Section 4.01: Taking of Certain Fish 4.02: Taking of Carp

321 CMR: DIVISION OF FISHERIES AND WILDLIFE 321 CMR 4.00: FISHING Section 4.01: Taking of Certain Fish 4.02: Taking of Carp and Suckers for the Purpose of Sale 4.03: Taking of Commercial Eels From Inland Waters 4.04: Taking of Fish in Interstate Ponds Lying Between Massachusetts and New Hampshire 4.05: Taking of Fish in Interstate Ponds Lying Between Massachusetts and Connecticut 4.06: Taking of Fish in Interstate Ponds Lying Between Massachusetts and Rhode Island 4.09: Propagation, Culture, Maintenance and Sale of Protected Freshwater Fish 4.01: Taking of Certain Fish In accordance with the authority vested in me by the provisions of M.G.L. c. 131, §§ 4, 5 and 51, I hereby declare an open season for the taking of fish throughout Massachusetts and promulgate the following rules and regulations relating to their taking as hereinafter provided: (1) Definitions: For the purposes of 321 CMR 4.01, the following words or phrases shall have the following meanings: Broodstock Salmon means an Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) that has been reared in a hatchery for purposes of spawning and subsequently released into the wild. Dealer means a person who commercially handles fish, birds, or mammals protected by M.G.L. c. 131 and who is licensed as a Class 6 dealer pursuant to M.G.L. c. 131, § 23. Director means the Director of the Division of Fisheries and Wildlife or his authorized agent. Float means any device, including a toggle, floating with a line and hook attached, baited with natural or artificial bait and not under the direct control of the hand of the person fishing. -

Massachusetts Estuaries Project

Massachusetts Estuaries Project Linked Watershed-Embayment Model to Determine Critical Nitrogen Loading Thresholds for Popponesset Bay, Mashpee and Barnstable, Massachusetts University of Massachusetts Dartmouth Massachusetts Department of School of Marine Science and Technology Environmental Protection FINAL REPORT – SEPTEMBER 2004 Massachusetts Estuaries Project Linked Watershed-Embayment Model to Determine Critical Nitrogen Loading Thresholds for Popponesset Bay, Mashpee and Barnstable, Massachusetts FINAL REPORT – SEPTEMBER 2004 Brian Howes Roland Samimy David Schlezinger Sean Kelley John Ramsey Jon Wood Ed Eichner Contributors: US Geological Survey Don Walters, and John Masterson Applied Coastal Research and Engineering, Inc. Elizabeth Hunt and Trey Ruthven Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection Charles Costello and Brian Dudley (DEP project manager) SMAST Coastal Systems Program Paul Henderson, George Hampson, and Sara Sampieri Cape Cod Commission Brian DuPont Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection Massachusetts Estuaries Project Linked Watershed-Embayment Model to Determine Critical Nitrogen Loading Thresholds for Popponesset Bay, Mashpee and Barnstable, Massachusetts Executive Summary 1. Background This report presents the results generated from the implementation of the Massachusetts Estuaries Project’s Linked Watershed-Embayment Approach to the Popponesset Bay System a coastal embayment within the Towns of Mashpee and Barnstable, Massachusetts. Analyses of the Popponesset Bay System was performed to assist the Towns with up-coming nitrogen management decisions associated with the Towns’ current and future wastewater planning efforts, as well as wetland restoration, anadromous fish runs, shell fishery, open-space, and harbor maintenance programs. As part of the MEP approach, habitat assessment was conducted on the embayment based upon available water quality monitoring data, historical changes in eelgrass distribution, time-series water column oxygen measurements, and benthic community structure. -

Annual Report 2018

Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife 2018 Annual Report 147 Annual Report 2018 Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife Jack Buckley Director (July 2017–May 2018) Mark S. Tisa, Ph.D., M.B.A. Acting Director (May–June 2018) 149 Table of Contents 2 The Board Reports 6 Fisheries 42 Wildlife 66 Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program 82 Information & Education 95 Archivist 96 Hunter Education 98 District Reports 124 Wildlife Lands 134 Federal Aid 136 Staff and Agency Recognition 137 Personnel Report 140 Financial Report Appendix A Appendix B About the Cover: MassWildlife staff prepare to stock trout at Lake Quinsigamond in Worcester with the help of the public. Photo by Troy Gipps/MassWildlife Back Cover: A cow moose stands in a Massachusetts bog. Photo by Bill Byrne/MassWildlife Printed on Recycled Paper. ELECTRONIC VERSION 1 The Board Reports Joseph S. Larson, Ph.D. Chairperson Overview fective April 30, 2018, and the Board voted the appoint- ment of Deputy Director Mark Tisa as Acting Director, The Massachusetts Fisheries and Wildlife Board con- effective Mr. Buckley’s retirement. The Board -mem sists of seven persons appointed by the Governor to bers expressed their gratitude and admiration to the 5-year terms. By law, the individuals appointed to the outgoing Director for his close involvement in develop- Board are volunteers, receiving no remuneration for ing his staff and his many accomplishments during his their service to the Commonwealth. Five of the sev- tenure, not only as Director but over his many years as en are selected on a regional basis, with one member, Deputy Director in charge of Administration, primarily by statute, representing agricultural interests. -

Body of Report

Streamflow Measurements, Basin Characteristics, and Streamflow Statistics for Low-Flow Partial-Record Stations Operated in Massachusetts from 1989 Through 1996 By Kernell G. Ries, III Abstract length; mean basin slope; area of surficial stratified drift; area of wetlands; area of water bodies; and A network of 148 low-flow partial-record mean, maximum, and minimum basin elevation. stations was operated on streams in Massachusetts Station descriptions and calculated streamflow during the summers of 1989 through 1996. statistics are also included in the report for the 50 Streamflow measurements (including historical continuous gaging stations used in correlations measurements), measured basin characteristics, with the low-flow partial-record stations. and estimated streamflow statistics are provided in the report for each low-flow partial-record station. Also included for each station are location infor- INTRODUCTION mation, streamflow-gaging stations for which flows were correlated to those at the low-flow Streamflow statistics are useful for design and operation of reservoirs for water supply and partial-record station, years of operation, and hydroelectric generation, sewage-treatment facilities, remarks indicating human influences of stream- commercial and industrial facilities, agriculture, flows at the station. Three or four streamflow mea- maintenance of streamflows for fisheries and wildlife, surements were made each year for three years and recreational users. These statistics provide during times of low flow to obtain nine or ten mea- indications of reliability of water resources, especially surements for each station. Measured flows at the during times when water conservation practices are low-flow partial-record stations were correlated most likely to be needed to protect instream flow and with same-day mean flows at a nearby gaging other uses. -

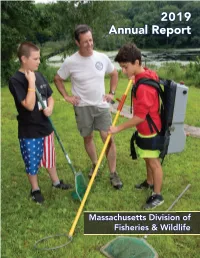

2019 Annual Report

2019 Annual Report Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife 161 Annual Report 2019 Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife Mark S. Tisa, Ph.D., M.B.A. Director 163 Table of Contents 2 The Board Reports 6 Fisheries 60 Wildlife 82 Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program 98 Information & Education 114 Hunter Education 116 District Reports 138 Wildlife Lands 149 Archivist 150 Federal Aid 152 Personnel Report 154 Financial Report Front Cover: Jim Lagacy, MassWildlife Angler Education Coordinator, teaches Fisheries Management to campers at the Massachusetts Junior Conservation Camp in Russell. Photo by Troy Gipps/MassWildlife Back Cover: A blue-spotted salamander (Ambystoma laterale), a state-listed Species of Special Concern, rests on an autumn leaf at the Wayne F. MacCallum Wildlife Management Area in Westborough. Photo by Troy Gipps/MassWildlife Printed on Recycled Paper. 1 The Board Reports Joseph S. Larson, Ph.D. Chairperson Overview 32 years of experience with MassWildlife, including as the The Massachusetts Fisheries and Wildlife Board consists Assistant Director of Fisheries for 25 years; as the Depu- of seven persons appointed by the Governor to 5-year ty Director of the agency for the previous 3 years (March terms. By law, the individuals appointed to the Board are 2015—April 2018); and most recently as its Acting Director, volunteers, receiving no remuneration for their service to effective April 30, 2018. The Fisheries and Wildlife Board ap- the Commonwealth. Five of the seven are selected on a pointed Director Tisa because of his lifelong commitment to regional basis, with one member, by statute, representing wildlife and fisheries conservation and his excellent record agricultural interests. -

Sheep and Wool in Nineteenth-Century Falmouth, MA: Examining the Collapse of a Cape Cod Industry Leo Patrick Ledwell University of Massachusetts Boston

University of Massachusetts Boston ScholarWorks at UMass Boston Graduate Masters Theses Doctoral Dissertations and Masters Theses 8-1-2012 Sheep and Wool in Nineteenth-Century Falmouth, MA: Examining the Collapse of a Cape Cod Industry Leo Patrick Ledwell University of Massachusetts Boston Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/masters_theses Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Ledwell, Leo Patrick, "Sheep and Wool in Nineteenth-Century Falmouth, MA: Examining the Collapse of a Cape Cod Industry" (2012). Graduate Masters Theses. Paper 121. This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Doctoral Dissertations and Masters Theses at ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SHEEP AND WOOL IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY FALMOUTH, MA: EXAMINING THE COLLAPSE OF A CAPE COD INDUSTRY A Thesis Presented by LEO PATRICK LEDWELL, JR. Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies, University of Massachusetts Boston in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2012 Historical Archaeology Program © 2012 by Leo Patrick Ledwell, Jr. All rights reserved SHEEP AND WOOL IN NINETEENTH-CENTURYFALMOUTH, MA: EXAMINING THE COLLAPSE OF A CAPE COD INDUSTRY A Thesis Presented by LEO PATRICK LEDWELL, JR. Approved as to style and content by: _______________________________________________ -

Town of Mashpee, Popponesset Bay, & Waquoit Bay East Watersheds

Town of Mashpee, Popponesset Bay, & Waquoit Bay East Watersheds TM Nitrex Technology Scenario Plan Submitted to: Town of Mashpee Submitted by: Sewer Commission 16 Great Neck Road North Mashpee, MA 02469 August 1, 2008 Town of Mashpee Sewer Commission August 1, 2008 Table of Contents Executive Summary........................................................................................................ 1 1 Objective................................................................................................................ 10 2 Background............................................................................................................ 10 2.1 Wastewater Flows .......................................................................................... 11 2.2 Hydrogeology ................................................................................................. 13 3 Needs Definition .................................................................................................... 20 3.1 Data Management - Methodology .................................................................. 20 3.2 Planning Area Parcel Summary...................................................................... 31 3.3 Nitrogen Loading and TMDLs......................................................................... 33 3.3.1 Data Overview......................................................................................... 34 3.3.2 Popponesset Bay Nitrogen Removal Requirements ............................... 38 3.3.3 East Waquoit Bay Nitrogen -

Annual Report Fiscal Year 2019

Annual Report Fiscal Year 2019 Over the past decade, the Town has partnered with more than 35 federal, state, regional and local agencies, organizations and private companies along with local, state and regional lead- ers to conduct the Coonamessett River Restoration Project. When completed in 2020, it will improve 56 acres of wetland and stream habitat along a mile of the lower Coonamessett River, increase coastal resiliency to expected effects of climate change, and provide new recreational and educational opportunities for the residents of Falmouth and the town’s many visitors. Its success is largely due to the contributions of hundreds of dedicated individuals, both those employed by partnering organizations and the many volunteers, who are passionate about improving the natural environment and leaving a positive legacy for the next generations. The Town of Falmouth Fiscal Year 2019 Annual Town Report Report coordinator: Diane S. Davidson, Office of the Town Manager and Board of Selectmen Cover photos provided by: Mark Kasprzyk, Alison Leschen, Jody Kiricich, Phil Beach, Elizabeth Gladfelter, and Diane Davidson Print services provided by: Heritage Print Solutions, Sandwich, MA This document may be viewed on the Town of Falmouth web site: www.falmouthmass.us Table of Contents Elected Town Officers ........................................................................................................................... 4 Board of Selectmen’s Report .................................................................................................................