Electronic Supplementary Material 1 Methods 2 Phylogeny 3 I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Osteological Development of Wild-Captured Larvae and a Juvenile Sebastes Koreanus (Pisces, Scorpaenoidei) from the Yellow Sea Hyo Jae Yu and Jin-Koo Kim*

Yu and Kim Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences (2016) 19:20 DOI 10.1186/s41240-016-0021-0 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Osteological development of wild-captured larvae and a juvenile Sebastes koreanus (Pisces, Scorpaenoidei) from the Yellow Sea Hyo Jae Yu and Jin-Koo Kim* Abstract The osteological development in Sebastes koreanus is described and illustrated on the basis of 32 larvae [6.11–11.10 mm body length (BL)] and a single juvenile (18.60 mm BL) collected from the Yellow Sea. The first-ossified skeletal elements, which are related to feeding, swimming, and respiration, appear in larvae of 6.27 mm BL; these include the jaw bones, palatine, opercular, hyoid arch, and pectoral girdle. All skeletal elements are fully ossified in the juvenile observed in the study. Ossification of the neurocranium started in the frontal, pterotic, and parietal regions at 6.27 mm BL, and then in the parasphenoid and basioccipital regions at 8.17 mm BL. The vertebrae had started to ossify at ~7.17 mm BL, and their ossification was nearly complete at 11.10 mm BL. In the juvenile, although ossification of the pectoral girdle was fully complete, the fusion of the scapula and uppermost radial had not yet occurred. Thus, the scapula and uppermost radial fuse during or after the juvenile stage. The five hypurals in the caudal skeleton were also fused to form three hypural elements. The osteological results are discussed from a functional viewpoint and in terms of the comparative osteological development in related species. Keywords: Sebastes koreanus, Korean fish, Larvae, Juvenile, Osteological development Background Sebastes koreanus Kim and Lee 1994, in the family Osteological development in teleost fishes involves a Scorpaenidae (or Sebastidae sensu Nakabo and Kai sequence of remarkable morphological and functional 2013), is smaller than its congeneric species and is changes, occurring in different developmental stages regarded as endemic to the Yellow Sea (Kim and Lee (Löffler et al. -

Management Plan for the Rougheye/Blackspotted Rockfish Complex (Sebastes Aleutianus and S

DRAFT SPECIES AT RISK ACT MANAGESPECIESMENT PLAN AT RISK SERIES ACT MANAGEMENT PLAN SERIES MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR THE ROUGHEYE/BLACKSPOTTEDMANAGEMENT PLAN FOR THE ROCKFISH ROUGHEY E COMPLEXROCKFISHROUGHEYE (SEBASTES ALEUTIANUSROCKFISH COMPLEX AND S. MELANOSTICTUS(SEBASTES ALEUTIANUS) AND LONGSPINE AND S. THORNYHEADMELANOSTICTUS (SEBASTOLOBUS) AND LONGSPINE ALTIVELIS THORNYHE) IN AD CANADA(SEBAST OLOBUS ALTIVELIS)INCANADA SEBASTES ALEUTIANUS; SEBASTES MELANOSTICTUS SEBASTES ASEBASTOLOBUSLEUTIANUS; SEBASTES ALTIVELIS MEL ANOSTICTUS SEBASTOLOBUS ALTIVELIS S. aleutianus S. melanostictus 2012 Photo Credit: DFO Sebastolobus altivelis 2012 About the Species at Risk Act Management Plan Series What is the Species at Risk Act (SARA)? SARA is the Act developed by the federal government as a key contribution to the common national effort to protect and conserve species at risk in Canada. SARA came into force in 2003, and one of its purposes is “to manage species of special concern to prevent them from becoming endangered or threatened.” What is a species of special concern? Under SARA, a species of special concern is a wildlife species that could become threatened or endangered because of a combination of biological characteristics and identified threats. Species of special concern are included in the SARA List of Wildlife Species at Risk. What is a management plan? Under SARA, a management plan is an action-oriented planning document that identifies the conservation activities and land use measures needed to ensure, at a minimum, that a species of special concern does not become threatened or endangered. For many species, the ultimate aim of the management plan will be to alleviate human threats and remove the species from the List of Wildlife Species at Risk. -

Southward Range Extension of the Goldeye Rockfish, Sebastes

Acta Ichthyologica et Piscatoria 51(2), 2021, 153–158 | DOI 10.3897/aiep.51.68832 Southward range extension of the goldeye rockfish, Sebastes thompsoni (Actinopterygii: Scorpaeniformes: Scorpaenidae), to northern Taiwan Tak-Kei CHOU1, Chi-Ngai TANG2 1 Department of Oceanography, National Sun Yat-sen University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan 2 Department of Aquaculture, National Taiwan Ocean University, Keelung, Taiwan http://zoobank.org/5F8F5772-5989-4FBA-A9D9-B8BD3D9970A6 Corresponding author: Tak-Kei Chou ([email protected]) Academic editor: Ronald Fricke ♦ Received 18 May 2021 ♦ Accepted 7 June 2021 ♦ Published 12 July 2021 Citation: Chou T-K, Tang C-N (2021) Southward range extension of the goldeye rockfish, Sebastes thompsoni (Actinopterygii: Scorpaeniformes: Scorpaenidae), to northern Taiwan. Acta Ichthyologica et Piscatoria 51(2): 153–158. https://doi.org/10.3897/ aiep.51.68832 Abstract The goldeye rockfish,Sebastes thompsoni (Jordan et Hubbs, 1925), is known as a typical cold-water species, occurring from southern Hokkaido to Kagoshima. In the presently reported study, a specimen was collected from the local fishery catch off Keelung, northern Taiwan, which represents the first specimen-based record of the genus in Taiwan. Moreover, the new record ofSebastes thompsoni in Taiwan represented the southernmost distribution of the cold-water genus Sebastes in the Northern Hemisphere. Keywords cold-water fish, DNA barcoding, neighbor-joining, new recorded genus, phylogeny, Sebastes joyneri Introduction On an occasional survey in a local fish market (25°7.77′N, 121°44.47′E), a mature female individual of The rockfish genusSebastes Cuvier, 1829 is the most spe- Sebastes thompsoni (Jordan et Hubbs, 1925) was obtained ciose group of the Scorpaenidae, which comprises about in the local catches, which were caught off Keelung, north- 110 species worldwide (Li et al. -

Pacific False Kelpfish, Sebastiscus Marmoratus (Cuvier, 1829) (Scorpaeniformes, Sebastidae) Found in Norwegian Waters

BioInvasions Records (2018) Volume 7, Issue 1: 73–78 Open Access DOI: https://doi.org/10.3391/bir.2018.7.1.11 © 2018 The Author(s). Journal compilation © 2018 REABIC Research Article Pacific false kelpfish, Sebastiscus marmoratus (Cuvier, 1829) (Scorpaeniformes, Sebastidae) found in Norwegian waters Haakon Hansen1,* and Egil Karlsbakk2 1Norwegian Veterinary Institute, P.O. Box 750 Sentrum, NO-0106 Oslo, Norway 2Department of Biology, University of Bergen, 5020 Bergen, Norway Author e-mails: [email protected] (HH), [email protected] (EK) *Corresponding author Received: 28 September 2017 / Accepted: 21 November 2017 / Published online: 1 December 2017 Handling editor: Henn Ojaveer Abstract During an angling competition in the Oslofjord, Southern Norway, a fish species previously unknown to the anglers was caught. Subsequent morphological studies and DNA barcoding identified it as a false kelpfish, Sebastiscus marmoratus (Cuvier, 1829), a species native to the Western Pacific from southern Hokkaido, Japan to the Philippines. The specimen was a female with a length of 29.2 cm and weighing 453 g. Stomach contents revealed fish remains, as well as the brachyuran Xantho pilipes A. Milne-Edwards, 1867 and remains of anomuran decapods. Parasitological examination revealed infections with the locally common generalist parasites Derogenes varicus (Digenea) and Hysterothylacium aduncum (Nematoda) that likely have been acquired through prey fish. A literature study of the parasites of S. marmoratus was carried out, listing at least 31 species. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of this fish species in the Atlantic. The introduction route is unknown, but the most likely possibility is via a ship’s ballast water as a larva or fry, which again would imply that the specimen has been in temperate waters for several years. -

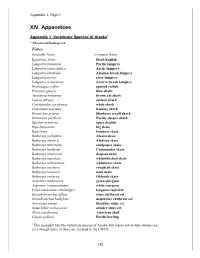

XIV. Appendices

Appendix 1, Page 1 XIV. Appendices Appendix 1. Vertebrate Species of Alaska1 * Threatened/Endangered Fishes Scientific Name Common Name Eptatretus deani black hagfish Lampetra tridentata Pacific lamprey Lampetra camtschatica Arctic lamprey Lampetra alaskense Alaskan brook lamprey Lampetra ayresii river lamprey Lampetra richardsoni western brook lamprey Hydrolagus colliei spotted ratfish Prionace glauca blue shark Apristurus brunneus brown cat shark Lamna ditropis salmon shark Carcharodon carcharias white shark Cetorhinus maximus basking shark Hexanchus griseus bluntnose sixgill shark Somniosus pacificus Pacific sleeper shark Squalus acanthias spiny dogfish Raja binoculata big skate Raja rhina longnose skate Bathyraja parmifera Alaska skate Bathyraja aleutica Aleutian skate Bathyraja interrupta sandpaper skate Bathyraja lindbergi Commander skate Bathyraja abyssicola deepsea skate Bathyraja maculata whiteblotched skate Bathyraja minispinosa whitebrow skate Bathyraja trachura roughtail skate Bathyraja taranetzi mud skate Bathyraja violacea Okhotsk skate Acipenser medirostris green sturgeon Acipenser transmontanus white sturgeon Polyacanthonotus challengeri longnose tapirfish Synaphobranchus affinis slope cutthroat eel Histiobranchus bathybius deepwater cutthroat eel Avocettina infans blackline snipe eel Nemichthys scolopaceus slender snipe eel Alosa sapidissima American shad Clupea pallasii Pacific herring 1 This appendix lists the vertebrate species of Alaska, but it does not include subspecies, even though some of those are featured in the CWCS. -

Venom Evolution Widespread in Fishes: a Phylogenetic Road Map for the Bioprospecting of Piscine Venoms

Journal of Heredity 2006:97(3):206–217 ª The American Genetic Association. 2006. All rights reserved. doi:10.1093/jhered/esj034 For permissions, please email: [email protected]. Advance Access publication June 1, 2006 Venom Evolution Widespread in Fishes: A Phylogenetic Road Map for the Bioprospecting of Piscine Venoms WILLIAM LEO SMITH AND WARD C. WHEELER From the Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Environmental Biology, Columbia University, 1200 Amsterdam Avenue, New York, NY 10027 (Leo Smith); Division of Vertebrate Zoology (Ichthyology), American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, NY 10024-5192 (Leo Smith); and Division of Invertebrate Zoology, American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, NY 10024-5192 (Wheeler). Address correspondence to W. L. Smith at the address above, or e-mail: [email protected]. Abstract Knowledge of evolutionary relationships or phylogeny allows for effective predictions about the unstudied characteristics of species. These include the presence and biological activity of an organism’s venoms. To date, most venom bioprospecting has focused on snakes, resulting in six stroke and cancer treatment drugs that are nearing U.S. Food and Drug Administration review. Fishes, however, with thousands of venoms, represent an untapped resource of natural products. The first step in- volved in the efficient bioprospecting of these compounds is a phylogeny of venomous fishes. Here, we show the results of such an analysis and provide the first explicit suborder-level phylogeny for spiny-rayed fishes. The results, based on ;1.1 million aligned base pairs, suggest that, in contrast to previous estimates of 200 venomous fishes, .1,200 fishes in 12 clades should be presumed venomous. -

A Checklist of the Fishes of the Monterey Bay Area Including Elkhorn Slough, the San Lorenzo, Pajaro and Salinas Rivers

f3/oC-4'( Contributions from the Moss Landing Marine Laboratories No. 26 Technical Publication 72-2 CASUC-MLML-TP-72-02 A CHECKLIST OF THE FISHES OF THE MONTEREY BAY AREA INCLUDING ELKHORN SLOUGH, THE SAN LORENZO, PAJARO AND SALINAS RIVERS by Gary E. Kukowski Sea Grant Research Assistant June 1972 LIBRARY Moss L8ndillg ,\:Jrine Laboratories r. O. Box 223 Moss Landing, Calif. 95039 This study was supported by National Sea Grant Program National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration United States Department of Commerce - Grant No. 2-35137 to Moss Landing Marine Laboratories of the California State University at Fresno, Hayward, Sacramento, San Francisco, and San Jose Dr. Robert E. Arnal, Coordinator , ·./ "':., - 'I." ~:. 1"-"'00 ~~ ~~ IAbm>~toriesi Technical Publication 72-2: A GI-lliGKL.TST OF THE FISHES OF TtlE MONTEREY my Jl.REA INCLUDING mmORH SLOUGH, THE SAN LCRENZO, PAY-ARO AND SALINAS RIVERS .. 1&let~: Page 14 - A1estria§.·~iligtro1ophua - Stone cockscomb - r-m Page 17 - J:,iparis'W10pus." Ribbon' snailt'ish - HE , ,~ ~Ei 31 - AlectrlQ~iu.e,ctro1OphUfi- 87-B9 . .', . ': ". .' Page 31 - Ceb1diehtlrrs rlolaCewi - 89 , Page 35 - Liparis t!01:f-.e - 89 .Qhange: Page 11 - FmWulns parvipin¢.rl, add: Probable misidentification Page 20 - .BathopWuBt.lemin&, change to: .Mhgghilu§. llemipg+ Page 54 - Ji\mdJ11ui~~ add: Probable. misidentifioation Page 60 - Item. number 67, authOr should be .Hubbs, Clark TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 AREA OF COVERAGE 1 METHODS OF LITERATURE SEARCH 2 EXPLANATION OF CHECKLIST 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 4 TABLE 1 -

Multiple Paternity and Maintenance of Genetic Diversity in the Live-Bearing Rockfishes Sebastes Spp

Vol. 357: 245–253, 2008 MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Published April 7 doi: 10.3354/meps07296 Mar Ecol Prog Ser Multiple paternity and maintenance of genetic diversity in the live-bearing rockfishes Sebastes spp. John R. Hyde1, 2,*, Carol Kimbrell2, Larry Robertson2, Kevin Clifford3, Eric Lynn2, Russell Vetter2 1Scripps Institution of Oceanography, 9500 Gilman Drive, La Jolla, California 92093-0203, USA 2Southwest Fisheries Science Center, NOAA/NMFS, 8604 La Jolla Shores Dr., La Jolla, California 92037, USA 3Oregon Coast Aquarium, 2820 SE Ferry Slip Rd, Newport, Oregon 97365, USA ABSTRACT: The understanding of mating systems is key to the proper management of exploited spe- cies, particularly highly fecund, r-selected fishes, which often show strong discrepancies between census and effective population sizes. The development of polymorphic genetic markers, such as codominant nuclear microsatellites, has made it possible to study the paternity of individuals within a brood, helping to elucidate the species’ mating system. In the present study, paternity analysis was performed on 35 broods, representing 17 species of the live-bearing scorpaenid genus Sebastes. We report on the finding of multiple paternity from several species of Sebastes and show that at least 3 sires can contribute paternity to a single brood. A phylogenetically and ecologically diverse sample of Sebastes species was examined, with multiple paternity found in 14 of the 35 broods and 10 of the 17 examined species, we suggest that this behavior is not a rare event within a single species and is likely common throughout the genus. Despite high variance in reproductive success, Sebastes spp., in general, show moderate to high levels of genetic diversity. -

Behaviour and Patterns of Habitat Utilisation by Deep-Sea Fish

Behaviour and patterns of habitat utilisation by deep-sea fish: analysis of observations recorded by the submersible Nautilus in "98" in the Bay of Biscay, NE Atlantic By Dário Mendes Alves, 2003 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master Science in International Fisheries Management Department of Aquatic Bioscience Norwegian College of Fishery Science University of Tromsø INDEX Abstract………………………………………………………………………………….ii Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………..iii page 1.INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………1 1.1. Deep-sea fisheries…………………………………………………………….……..1 1.2. Deep-sea habitats……………………………………………………………………2 1.3. The Bay of Biscay…………………………………………………………………..3 1.4. Deep-sea fish locomotory behaviour………………………………………………..4 1.5. Objectives……………………………………………………………………...……4 2.MATERIAL AND METHODS…………………………………………….…..……5 2.1. Dives, data collection and environments……………………………………………5 2.2. Video and data analysis……………………………………………………...……...7 2.2.1. Video assessment and sampling units………………………………...…..7 2.2.2. Microhabitats characterization…………………………………….……...8 2.2.3. Grouping of variables……………………………………………………10 2.2.4. Co-occurrence of fish and invertebrate fauna……………………………10 2.2.5. Depth and temperature relationships…………………………………….10 2.2.6. Multivariate analysis……………………………………………………..11 2.2.7. Locomotory Behaviour………………………………………………......13 3.RESULTS……………………………………………………………………………14 3.1. General characterization of dives………………………………………………….14 3.1.1. Species richness, habitat types and sampling……………………………14 3.1.2. Diving profiles, depth and temperature………………………………….17 3.1.3. Fish distribution according to depth and temperature………………...…18 3.2. Habitat use………………………………………………………………………....20 3.2.1. Independent dive analysis……………………………………………..…20 3.2.1.1. Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA), Dive 22……………...…..20 3.2.1.2. Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA), Dive 34………………….22 3.2.1.3. Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA), Dive 35………………….24 3.2.1.4. -

Population Genetic Structure of Marbled Rockfish, Sebastiscus Marmoratus (Cuvier, 1829), in the Northwestern Pacific Ocean

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 830: 127–144Population (2019) genetic structure of Marbled Rockfish,Sebastiscus marmoratus... 127 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.830.30586 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Population genetic structure of Marbled Rockfish, Sebastiscus marmoratus (Cuvier, 1829), in the northwestern Pacific Ocean Lu Liu1, Xiumei Zhang1,2, Chunhou Li3, Hui Zhang4, Takashi Yanagimoto5, Na Song1, Tianxiang Gao6 1 The Key Laboratory of Mariculture (Ocean University of China), Ministry of Education, 266071 Qingdao, China 2 Laboratory for Marine Fisheries and Aquaculture, Qingdao National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology, 266072 Qingdao, China 3 South China Sea Fisheries Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences, 510003 Guangzhou, China 4 Key Laboratory of Marine Ecology and Environment Sciences, Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 266071 Qingdao, China 5 National Research Institute of Fisheries Science, Japan Fisheries Research and Education Agency, 2368648 Yokohama, Japan 6 Fisheries College, Zhejiang Ocean University, 316000 Zhoushan, China Corresponding author: Tianxiang Gao ([email protected]) Academic editor: M.E. Bichuette | Received 16 October 2018 | Accepted 2 February 2019 | Published 14 March 2019 http://zoobank.org/11C4F8F6-256F-4C41-A961-A2847CE94D4F Citation: Liu L, Zhang X, Li C, Zhang H, Yanagimoto T, Song N, Gao T (2019) Population genetic structure of Marbled Rockfish,Sebastiscus marmoratus (Cuvier, 1829), in the northwestern Pacific Ocean. ZooKeys 830: 127–144. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.830.30586 Abstract Sebastiscus marmoratus is an ovoviviparous fish widely distributed in the northwestern Pacific. To examine the gene flow and test larval dispersal strategy of S. marmoratus in Chinese and Japanese coastal waters, 421 specimens were collected from 22 localities across its natural distribution. -

Approved List of Japanese Fishery Fbos for Export to Vietnam Updated: 11/6/2021

Approved list of Japanese fishery FBOs for export to Vietnam Updated: 11/6/2021 Business Approval No Address Type of products Name number FROZEN CHUM SALMON DRESSED (Oncorhynchus keta) FROZEN DOLPHINFISH DRESSED (Coryphaena hippurus) FROZEN JAPANESE SARDINE ROUND (Sardinops melanostictus) FROZEN ALASKA POLLACK DRESSED (Theragra chalcogramma) 420, Misaki-cho, FROZEN ALASKA POLLACK ROUND Kaneshin Rausu-cho, (Theragra chalcogramma) 1. Tsuyama CO., VN01870001 Menashi-gun, FROZEN PACIFIC COD DRESSED LTD Hokkaido, Japan (Gadus macrocephalus) FROZEN PACIFIC COD ROUND (Gadus macrocephalus) FROZEN DOLPHIN FISH ROUND (Coryphaena hippurus) FROZEN ARABESQUE GREENLING ROUND (Pleurogrammus azonus) FROZEN PINK SALMON DRESSED (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha) - Fresh fish (excluding fish by-product) Maekawa Hokkaido Nemuro - Fresh bivalve mollusk. 2. Shouten Co., VN01860002 City Nishihamacho - Frozen fish (excluding fish by-product) Ltd 10-177 - Frozen processed bivalve mollusk Frozen Chum Salmon (round, dressed, semi- dressed,fillet,head,bone,skin) Frozen Alaska Pollack(round,dressed,semi- TAIYO 1-35-1 dressed,fillet) SANGYO CO., SHOWACHUO, Frozen Pacific Cod(round,dressed,semi- 3. LTD. VN01840003 KUSHIRO-CITY, dressed,fillet) KUSHIRO HOKKAIDO, Frozen Pacific Saury(round,dressed,semi- FACTORY JAPAN dressed) Frozen Chub Mackerel(round,fillet) Frozen Blue Mackerel(round,fillet) Frozen Salted Pollack Roe TAIYO 3-9 KOMABA- SANGYO CO., CHO, NEMURO- - Frozen fish 4. LTD. VN01860004 CITY, - Frozen processed fish NEMURO HOKKAIDO, (excluding by-product) FACTORY JAPAN -

Fishes-Of-The-Salish-Sea-Pp18.Pdf

NOAA Professional Paper NMFS 18 Fishes of the Salish Sea: a compilation and distributional analysis Theodore W. Pietsch James W. Orr September 2015 U.S. Department of Commerce NOAA Professional Penny Pritzker Secretary of Commerce Papers NMFS National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Kathryn D. Sullivan Scientifi c Editor Administrator Richard Langton National Marine Fisheries Service National Marine Northeast Fisheries Science Center Fisheries Service Maine Field Station Eileen Sobeck 17 Godfrey Drive, Suite 1 Assistant Administrator Orono, Maine 04473 for Fisheries Associate Editor Kathryn Dennis National Marine Fisheries Service Offi ce of Science and Technology Fisheries Research and Monitoring Division 1845 Wasp Blvd., Bldg. 178 Honolulu, Hawaii 96818 Managing Editor Shelley Arenas National Marine Fisheries Service Scientifi c Publications Offi ce 7600 Sand Point Way NE Seattle, Washington 98115 Editorial Committee Ann C. Matarese National Marine Fisheries Service James W. Orr National Marine Fisheries Service - The NOAA Professional Paper NMFS (ISSN 1931-4590) series is published by the Scientifi c Publications Offi ce, National Marine Fisheries Service, The NOAA Professional Paper NMFS series carries peer-reviewed, lengthy original NOAA, 7600 Sand Point Way NE, research reports, taxonomic keys, species synopses, fl ora and fauna studies, and data- Seattle, WA 98115. intensive reports on investigations in fi shery science, engineering, and economics. The Secretary of Commerce has Copies of the NOAA Professional Paper NMFS series are available free in limited determined that the publication of numbers to government agencies, both federal and state. They are also available in this series is necessary in the transac- exchange for other scientifi c and technical publications in the marine sciences.