THEODORA ALLEN Press Highlights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2001 Commencement Program

Morehead State University TM Class of 2001 Spring Commencement Saturday,Mayl2,2001 .... (lJ µ c:: V) CJ C: u o ·c ·~..,._ OJ 0. ...c:: <1) µ u~ <1) \ ~ -~ <1) s ti.I) <1) <1) -0 ~ c'O u~0 u -----------------U.S. 60 -------- The University Mace The practice of carrying a mace in academic processions dates to medieval times in England when a person bearing a mace, a formidable weapon, walked in front of the highest-ranking official as they entered and departed ceremonial occasions, to protect him or her from personal injury. As adapted by European and American universities, the mace has become a symbol of office of the institution's president and is carried by a distinguished member of the faculty. At Morehead State, the joint office of faculty grand marshal and mace bearer is held by the current recipient of the Distinguished Teacher Award. The mace of Morehead State University was fashioned from Eastern Kentucky Alma Mater walnut in 1984 by John S. VanHoose, a retired faculty member from the Depart (The audience is invited co participate.) ment of Industrial Education and Technology. Far above the rolling campus, Resting in the dale, Stands the dear old Alma Mater We will always hail. Shout in chorus, raise your voices, Safety Notices Blue and Gold-praise you. To ensure your safety during today's ceremony please take note of the Winning through to fame and glory, following: Dear old MSU. 1. Smoking, lighters, and open flames are not permitted in the arena at any time. 2. Please take note of your nearest exit. -

Eddy Arnold Cattle Call Free Download Cattle Call

eddy arnold cattle call free download Cattle Call. Purchase and download this album in a wide variety of formats depending on your needs. Buy the album Starting at £12.99. Copy the following link to share it. You are currently listening to samples. Listen to over 70 million songs with an unlimited streaming plan. Listen to this album and more than 70 million songs with your unlimited streaming plans. 1 month free, then £14,99/ month. Eddy Arnold, Associated Performer, Main Artist, Associated Performer - Chet Atkins, Producer - Traditional, Composer, Lyricist. Originally released 1963. All rights reserved by Sony Music Entertainment. Eddy Arnold, Associated Performer, Main Artist, Associated Performer - Chet Atkins, Producer - Bob Nolan, Composer, Lyricist. Originally released 1963. All rights reserved by Sony Music Entertainment. Eddy Arnold, Associated Performer, Main Artist, Associated Performer - Tex Owens, Composer, Lyricist - Chet Atkins, Producer. Originally released 1963. All rights reserved by Sony Music Entertainment. Eddy Arnold, Associated Performer, Main Artist, Associated Performer - Chet Atkins, Producer - Charles Kenny, Composer, Lyricist - Nick Kenny, Composer, Lyricist. Originally released 1963. All rights reserved by Sony Music Entertainment. Eddy Arnold, Associated Performer, Main Artist, Associated Performer - Chet Atkins, Producer - Jimmy Kennedy, Composer, Lyricist - Michael Carr, Composer, Lyricist. Originally released 1963. All rights reserved by Sony Music Entertainment. Eddy Arnold, Associated Performer, Main Artist, Associated Performer - Traditional, Composer, Lyricist - Chet Atkins, Producer. Originally released 1963. All rights reserved by Sony Music Entertainment. Eddy Arnold, Associated Performer, Main Artist, Associated Performer - Chet Atkins, Producer - Stan Lebowsky, Composer, Lyricist - Herb Newman, Composer, Lyricist. Originally released 1963. All rights reserved by Sony Music Entertainment. -

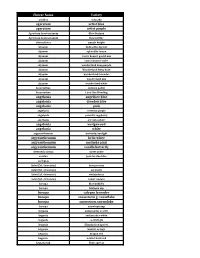

Horse Pedigrees

Name Sex Color Date of Foaling Sire Sire From Dam Dam From A CERTAIN SMILE FILLY BAY 27/03/2016 BOROBUDUR USA BEAUX YEUX PHI A ROSE FOR MARY FILLY BAY 01/03/2011 ECSTATIC USA SCARLET ONE USA A SONG FOR GEE FILLY BAY 17/03/2016 WARRIOR SONG USA GEE'S MELODY AUS A THOUSAND YEARS FILLY BAY 25/04/2012 SIR CHEROKEE USA CONCORDE A TOY FOR US HORSE BAY 18/03/2005 RIVER TRAFFIC USA MONTY'S ANGEL PHI A.P. FACTOR COLT GREY 27/04/2016 THE FACTOR USA CATBABY USA ABAKADA COLT BAY 14/03/2014 SHINING FAME PHI BETRUETOME ABANTERO COLT CH 20/04/2011 ART MODERNE USA PRINCESS HILTON AUS ABEL ILOKO COLT BAY 02/03/2014 QUAKER RIDGE USA MEADOW MYSTERY USA ABLE MINISTER FILLY BAY 09/03/2010 MAGIC OF SYDNEY USA CIELY GIRL USA ABOVE THE KNEE FILLY BAY 19/04/2011 RANDWICK USA BOLD SHOWING AUS ABSOLUTE WINNER COLT BAY 26/02/2014 ZAP USA BLUE MONTAGE AUS ABSOLUTERESISTANCE COLT BAY 26/03/2013 CONSOLIDATOR USA ELUSIVE PAST USA ACE GRANT FILLY BAY 01/03/2015 ART MODERNE USA IMMENSELY PHI ACE OF DIAMOND COLT DB/BR 25/05/2012 TATA RA AUS MISS BELAFONTE AUS ACE UP FILLY GRAY 21/02/2015 TRUST N LUCK USA NAME THIS TUNE USA ACTION RULES FILLY CH 01/02/2017 JUGGLING ACT AUS SPARKLING RULE PHI ACTION SAILOR HORSE DB/BR 23/05/2006 SAIL AWAY USA CAT'S BELLE AUS ADAMAS COLT BAY 03/03/2010 PRINCIPALITY USA MATERIALES FUERTES PHI ADARNA'S LANE FILLY CH 24/02/2009 FAR LANE USA ADARNA PHI ADDVIEDOUR COLT BAY 03/02/2014 ORAHTE AUS ADDED VALUE USA ADIOS REALITY HORSE GREY 07/04/2013 TAPIT USA DREAM RUSH USA ADORABLE FELICIA FILLY BAY 07/03/2014 GOLDSVILLE USA SALON LUMIERE AUS ADVANCING STAR FILLY CH 10/03/2013 CONSOLIDATOR USA IRON LADY AUS AERIAL FILLY BAY 05/01/2013 SAFE IN THE USA USA MARIA BET PHI AERO TAP FILLY BAY 27/02/2014 RETAP USA MAE WEST AFTER DARK FILLY BAY 17/07/2013 WINEMASTER USA STOWAWAY LASS AUS AGAINTS ALL ODDS FILLY BAY 01/03/2012 NOW A VICTOR USA PAMANA PHI AGAZZI COLT D. -

Download the Print Version of Inside Stanford

Over her years as a patient, Misty Blue Foster has found STANFORD kindness and encouragement at the children’s hospital. INSIDE Page 4 Volume 8, No. 19MEDICINE October 24, 2016 Published by the Office of Communication & Public Affairs Unroofing relieves symptoms of heart anomaly By Tracie White Myocardial bridging remains a mys- stood and is often misdiagnosed, Boyd her path of investigation. She wanted tery to much of the medical community. said. to know more: Could bridging be dan- n 2010, Ingela Schnittger, MD, a car- It’s a congenital anomaly that was discov- “It’s not taught in medical school, gerous? Did it cause symptoms? How diologist at the School of Medicine, ered during autopsies almost 300 years and there is no agreed-upon treatment,” should it be treated? Isat in her lab examining the echocar- ago, but it has long been considered be- he said. In 2011, Schnittger designed a study diogram of a young man who came to nign, the study said. That lack of understanding about the at Stanford to enroll patients with un- the heart clinic at Stanford Health Care Bridging continues to be little under- condition is what sent Schnittger along diagnosed See UNROOFING, page 6 complaining of chest pain. She spotted a curious motion of the heart on the com- AKSABIR / SHUTTERSTocK.coM puter screen, one that she’d seen before while examining these kinds of diagnos- tic tests. “All of the sudden I had this flash- back,” she said. She remembered a young physics professor at another institution who had suddenly dropped dead of a heart attack while running on a tread- mill. -

MCA Discography

MCA-1 Discography by David Edwards, Mike Callahan & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan MCA Discography Note: When MCA discontinued Decca, Uni, Kapp and their subsidiary labels in late 1972, they started the new MCA label by consolidating artists from those old labels into the new label. Starting in 1973, MCA reissued hundreds of albums from all of those labels with new catalog numbers under the new MCA imprint. They started these reissues in the MCA-1 reissue series, which ran to MCA-299. MCA MCA-1 Reissue Series: MCA 1 - Loretta Lynn’s Greatest Hits - Loretta Lynn [1973] Reissue of Decca DL7 5000. Don't Come Home A Drinkin'/Before I'm Over You/If You're Not Gone Too Long/Dear Uncle Sam/Other Woman/Wine Women And Song//You Ain't Woman Enough/Blue Kentucky Girl/Success/Home You're Tearin' Down/Happy Birthday MCA 2 - This Is Jerry Wallace - Jerry Wallace [1973] Reissue of Decca DL7 5294. After You/She'll Remember/The Greatest Love/In The Misty Moonlight/New Orleans In The Rain/Time//The Morning After/I Can't Take It Any More/The Hands Of The Man/To Get To You/There She Goes MCA 3 - Rick Nelson in Concert - Rick Nelson [1973] Reissue of Decca DL7 5162. Come On In/Hello Mary Lou, Goodbye Heart/Violets Of Dawn/Who Cares About Tomorrow-Promises/She Belongs To Me/If You Gotta Go, Go Now//I'm Walkin'/Red Balloon/Louisiana Man/Believe What You Say/Easy To Be Free/I Shall Be Released MCA 4 - Sousa Marches in Hi-Fi - Goldman Band [1973] Reissue of Decca DL7 8807. -

Web Plant Lists 16.Xlsx

Flower Name Variety achillea colorado ageratum artist blue ageratum artist purple Ageratum houstonianum Blue Horizon Ageratum houstonianum Hawaii Blue alternathera purple knight alyssum Aphrodite Apricot alyssum aphrodite lemon alyssum easter bonnet pastel mix alyssum easter bonnet violet alyssum wonderland deep purple alyssum Wonderland Deep Rose alyssum wonderland lavender alyssum wonderland mix alyssum wonderland white Amaranthus autumn pallet Amaranthus Love Lies Bleeding angelonia angelface blue angelonia dresden blue angelonia pink angelonia serenita purple angelonia serenita raspberry angelonia serenita white angelonia wedgewood angelonia white argyranthemum butterfly/sunlight argyranthemum helio white argyranthemum molimba pink argyranthemum vanilla butterfly Artemesia annua sweet annie asarina joan loraine blue asclepias Aster(Cal. chinensis) bouquet mix Aster(Cal. chinensis) serenade Aster(Cal. chinensis) siedajadama Aster(Cal. chinensis) tower custom bacopa blue bubbles bacopa blutopia mp bacopa calypso lavender bacopa snowstorm g. snowflake bacopa snowstorm snowglobe bacopa snowtopia mp begonia ambassador scarlet begonia ambassador white begonia cocktail gin begonia illumination apricot begonia bonfire orange begonia dragon red begonia mistral dark red begonia tub illum apricot begonia tub illum golden picotee begonia tub illum salmon pink begonia tub miss montreal begonia tub moccha deep orange begonia tub moccha scarlet begonia tub moccha white begonia tub moccha yellow begonia tub ns appleblossom begonia tub ns deep orange -

Artist Song Album Blue Collar Down to the Line Four Wheel Drive

Artist Song Album (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Blue Collar Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Down To The Line Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Four Wheel Drive Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Free Wheelin' Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Gimme Your Money Please Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Hey You Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Let It Ride Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Lookin' Out For #1 Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Roll On Down The Highway Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Take It Like A Man Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Takin' Care Of Business Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive You Ain't Seen Nothing Yet Best Of BTO (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive Takin' Care Of Business Hits of 1974 (BTO) Bachman-Turner Overdrive You Ain't Seen Nothin' Yet Hits of 1974 (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Can't Get It Out Of My Head Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Evil Woman Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Livin' Thing Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Ma-Ma-Ma Belle Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Mr. Blue Sky Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Rockaria Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Showdown Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Strange Magic Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Sweet Talkin' Woman Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Telephone Line Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Turn To Stone Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Can't Get It Out Of My Head Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Evil Woman Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Livin' Thing Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Ma-Ma-Ma Belle Greatest Hits of ELO (ELO) Electric Light Orchestra Mr. -

19 6 10700 Venlura Blvd CYCLE NO 7 6 2 PROGRAM S__ of 13 No Hollywood" Ca 91604 Phone (2131 980-9490 SIDES" ______::L::::.A~&~L::.:B~--.----- PAGE NO

-~~"""" " '_ r:~- " . -~. ,.""" -:' . -~ 7 WATBMWH FOR WEEK ENDING: May l' 19 6 10700 Venlura Blvd CYCLE NO 7 6 2 PROGRAM_S__ OF 13 No Hollywood" Ca 91604 Phone (2131 980-9490 SIDES" ________::l::::.A~&~l::.:B~--.----- PAGE NO SCHEDULED ACTUAl RUNNING ELEMENT START TIME TIME TIME 00:00 OPENING/THEME: "SHUCKATOOM" THEME FROM AMERICAN TOP FORTY (MARKWATER MUSIC/BMI) #40 - ANYTIME (I 1 LL BE THERE ) - Paul Anka 7:18 #3 9 - CAN'T HIDE LOVE - Earth, Wind & Fire 7:16 LOGO: CASEY'S COAST TO COAST 7:18 LOCAL INSERT C-1 2:00 9:18 LOGO: AMERICAN TOP 40 #38 - HURT - Elvis Presley #3 7 - I'VE GOT A FEELING - Al Wilson 9:26 #36 - MORE, MORE, MORE - Andrea True Connection ~8:42 LOGO: HITS FROM COAST TO COAST I 118:44 LOCAL INSERT C-2 2:00 I 20:44 LOGO: AMERICAN TOP 40 #35 - LOVE REALLY HURTS w·ITHOUT YOU - Billy Ocean 6:39 #34 - LOVE IN THE SHADOWS - Neil Sed aka i 27:21 LOGO: CASEY'S COAST TO COAST I 27:23 LOCAL INSERT: C-3 2:10 ~9:33 LOGO: AMERICAN TOP 40 #33 - UNION MAN - cate Bros. 7:51 #32 - YOUNG BLOOD - Bad Company ~7:22 LOGO: HITS FROM COAST TO COAST l37·24 LOCAL INSERT C-4 2:00 ~9:24 LOGO: AMERICAN TOP 40 #31 - SHOUT IT OUT LOUD - Kiss #30 - HAPPY MUSIC - Blackbyrds 10:35 #29 - COME ON OVER - Olivia Newton-John ~9:57 LOGO: CASEY'S COAST TO COAST ~9:59 LOCAL INSERT C-5 2:00 I 51:59 LOGO: AMERICAN TOP 40 #28 - DON'T PULL YOUR LOVE/THEN YOU CAN TELL ME GOODBY~ - Glen Campbell ~ #27 - S~vEET THING - Rufus Featuring Chaka Khan 6:32 58:31 THEME UP & UNDER W/TALK UNIT ENDING AT: 58:39 ' THEME TO: 58:50 58:50 LOCAL INSERT: C-6 :60 lc:; q. -

01. When the Saints Go Marching in 02. Bye Bye Blackbird 03. Cry Me A

01. When the Saints go Marching In 02. Bye Bye Blackbird 03. Cry Me A River 04. Sing, Sing, Sing 05. Summertime 06. Charleston 07. Hello Dolly 08. Manana (Is soon enough for me) 09. Fly Me To The Moon 10. Blue Moon 11. The Man I Love 12. Willow Weep For Me. 13. Nice Work If You Can Get It 14. My Funny Valentine 15. New York State Of Mind 16. You Might Need Somebody 17. Exactly Like You 18. Beautiful Love 19. Blame It On My Youth 20.Don't Go To Strangers 21. Here's That Rainy Day 22. I Thought About You 23. Lush Life 24. Afro Blue 25. After You've Gone 26. The Lady's In Love With You 27. On The Sunny Side Of The Street 28. Get Happy 29. It Don't Mean A Thing 30. Is It A Crime 31. Cherish The Day 32. No Ordinary Love 33. How High The Moon 34. 'Round Midnight 35. Night And Day 36. Love Me Or Leave Me 37. God Bless The Child 38. Opus 1 39. This Masquerade 40. The Masquerade Is Over 41. Tell Me All About It 42. Wild Is The Wind 43. Lullaby Of Birdland 44. All of Me 45. Autumn Leaves 46. Dream A Little Dream Of Me 47. Oh, Lady Be Good 48. It's Only A Papermoon 49. Strangers In The Night 50. Moonlight In Vermont 51. Come Rain Or Come Shine 52. The Shadow Of Your Smile 53. Why Don't You Do Right 54. All The Things You Are 55. -

“The Stories Behind the Songs”

“The Stories Behind The Songs” John Henderson The Stories Behind The Songs A compilation of “inside stories” behind classic country hits and the artists associated with them John Debbie & John By John Henderson (Arrangement by Debbie Henderson) A fascinating and entertaining look at the life and recording efforts of some of country music’s most talented singers and songwriters 1 Author’s Note My background in country music started before I even reached grade school. I was four years old when my uncle, Jack Henderson, the program director of 50,000 watt KCUL-AM in Fort Worth/Dallas, came to visit my family in 1959. He brought me around one hundred and fifty 45 RPM records from his station (duplicate copies that they no longer needed) and a small record player that played only 45s (not albums). I played those records day and night, completely wore them out. From that point, I wanted to be a disc jockey. But instead of going for the usual “comedic” approach most DJs took, I tried to be more informative by dropping in tidbits of a song’s background, something that always fascinated me. Originally with my “Classic Country Music Stories” site on Facebook (which is still going strong), and now with this book, I can tell the whole story, something that time restraints on radio wouldn’t allow. I began deejaying as a career at the age of sixteen in 1971, most notably at Nashville’s WENO-AM and WKDA- AM, Lakeland, Florida’s WPCV-FM (past winner of the “Radio Station of the Year” award from the Country Music Association), and Springfield, Missouri’s KTTS AM & FM and KWTO-AM, but with syndication and automation which overwhelmed radio some twenty-five years ago, my final DJ position ended in 1992. -

Mandisa Holmes, Esq

Flower Ladies Honorary Flower Ladies Heart and Spirit Speaks Taka Foster Amanda Oliver Tia Moore Domonica Starks When I heard the news Amy Davis Nikki Rush My heart sung the blues, Tiffanie Wilson Rashan Canady My brain refused to believe Desirre Starks The reality I had to perceive. Keilonda McCathern Pain so deep Pallbearers Honorary Pallbearers I cannot sleep, Derrick Humphrey Heart crying out Craig Collins, Sr. Jeremy Moore Soul screams and shout. James T. Ross Jemel Officer Leon E. Love It’s not fair Dondre L. Holmes Jamir John-Holmes That you are no longer there , Macieo Gaines Isaiah Holmes I need you here Tyria Love To give me cheer. An angel called home ACKNOWLEDGEMENT To stand beside His throne You have earned your wings During our time of sadness, sorrow and separation, we In heaven you sing. learn how much our friends mean to us. Your kindness and sympathy will always be remembered by… Halo shining bright Illuminated by Holy Light -The Family Wings pure white As you take flight. Services Entrusted to: Heart forever sad Neuble Monument Wishing that I had, Funeral Home, LLC In Loving Memory One more day Just to say. I love you Mandisa. James L. Neuble, Jr. Owner/Funeral Director Mandisa Laini Holmes, Esquire Stacy Neuble Co-Owner/Assistant Friday · February 28, 2020 · 1:00 PM - Your broken hearted brother, FIRST UNITED METHODIST CHURCH 1330 Bluebird Road ∙ Lebanon, TN ∙ 615.444.3117 www.neublemonumentfuneralhome.com 415 West Main Street · Lebanon, TN 37087 Jelani Eulogist: Pastor Michael Ruttlen Another Creation by Cynthia and Ronye · 615.893.7771 ORDER OF CELEBRATION Until We Meet Again Officiating, Minister John C. -

The Mississippi Mass Choir

R & B BARGAIN CORNER Bobby “Blue” Bland “Blues You Can Use” CD MCD7444 Get Your Money Where You Spend Your Time/Spending My Life With You/Our First Feelin's/ 24 Hours A Day/I've Got A Problem/Let's Part As Friends/For The Last Time/There's No Easy Way To Say Goodbye James Brown "Golden Hits" CD M6104 Hot Pants/I Got the Feelin'/It's a Man's Man's Man's World/Cold Sweat/I Can't Stand It/Papa's Got A Brand New Bag/Feel Good/Get on the Good Foot/Get Up Offa That Thing/Give It Up or Turn it a Loose Willie Clayton “Gifted” CD MCD7529 Beautiful/Boom,Boom, Boom/Can I Change My Mind/When I Think About Cheating/A LittleBit More/My Lover My Friend/Running Out of Lies/She’s Holding Back/Missing You/Sweet Lady/ Dreams/My Miss America/Trust (featuring Shirley Brown) Dramatics "If You come Back To Me" CD VL3414 Maddy/If You Come Back To Me/Seduction/Scarborough Faire/Lady In Red/For Reality's Sake/Hello Love/ We Haven't Got There Yet/Maddy(revisited) Eddie Floyd "Eddie Loves You So" CD STAX3079 'Til My Back Ain't Got No Bone/Since You Been Gone/Close To You/I Don't Want To Be With Nobody But You/You Don't Know What You Mean To Me/I Will Always Have Faith In You/Head To Toe/Never Get Enough of Your Love/You're So Fine/Consider Me Z. Z.