For Peer Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

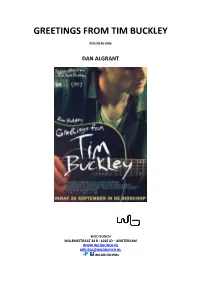

Greetings from Tim Buckley

GREETINGS FROM TIM BUCKLEY EEN FILM VAN DAN ALGRANT WILD BUNCH WILLEMSSTRAAT 24 B - 1015 JD – AMSTERDAM WWW.WILDBUNCH.NL [email protected] WILDBUNCHblx GREETINGS FROM TIM BUCKLEY – DAN ALGRANT PROJECT SUMMARY EEN PRODUCTIE VAN FROM A TO Z PRODUCTIONS, SMUGGLER FILMS TAAL ENGELS LENGTE 99 MINUTEN GENRE DRAMA LAND VAN HERKOMST USA FILMMAKER DAN ALGRANT HOOFDROLLEN PENN BADGLEY, IMOGEN POOTS RELEASEDATUM 26 SEPTEMBER 2013 KIJKWIJZER SYNOPSIS In 1991 repeteert een jonge Jeff Buckley voor zijn optreden tijdens een tribute show ter ere van zijn vader, wijlen volkszanger Tim Buckley. Terwijl hij worstelt met de erfenis van een man die hij nauwelijks kende, vormt Jeff een vriendschap met een mysterieuze jonge vrouw die bij de show werkt en begint hij de potentie van zijn eigen muzikale stem te ontdekken. CAST JEFF PENN BADGLEY ALLIE IMOGEN POOTS TIM BEN ROSENFIELD GARY FRANK WOOD JEN JENNIFER TURNER CAROL KATE NASH JANE ISABELLE MCNALLY LEE WILLIAM SADLER HAL NORBERT LEO BUTZ YOUNG LINDA JADYN STRAND RICHARD FRANK BELLO JANINE NICHOLS JESSICA STONE YOUNG LEE TYLER GILHAM SIRENS KEMP AND EDEN C.H. DAVID SCHNIRMAN CARTER STEPHEN TYRONE WILLIAMS MILOS CHRISTOPH MANUEL FRANK DAVID LIPMAN GARY LUCAS GARY LUCAS CREW DIRECTOR DAN ALGRANT SCREENWRITER DAN ALGRANT DAVID BRENDEL EMMA SHEANSHANG CINEMATOGRAPHER ANDRIJ PAREKH EDITOR BILL PANKOW CASTING AVY KAUFMAN PRODUCTION DESIGN JOHN PAINO COSTUME DESIGN DAVID C. ROBINSON ORIGINAL MUSIC GARY LUCAS GREETINGS FROM TIM BUCKLEY – DAN ALGRANT DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT Before GREETINGS FROM TIM BUCKLEY, I had made two short films about my father. When I was 21, I made the first film about how much I hated him when he left my mother. -

Fourth Amendment--Requiring Probable Cause for Searches and Seizures Under the Plain View Doctrine Elsie Romero

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 78 Article 3 Issue 4 Winter Winter 1988 Fourth Amendment--Requiring Probable Cause for Searches and Seizures under the Plain View Doctrine Elsie Romero Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Elsie Romero, Fourth Amendment--Requiring Probable Cause for Searches and Seizures under the Plain View Doctrine, 78 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 763 (1987-1988) This Supreme Court Review is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 0091-4169/88/7804-763 THE JOURNAL OF CRIMINAL LAw & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 78, No. 4 Copyright @ 1988 by Northwestern University, School of Law Printed in U.S.A. FOURTH AMENDMENT-REQUIRING PROBABLE CAUSE FOR SEARCHES AND SEIZURES UNDER THE PLAIN VIEW DOCTRINE Arizona v. Hicks, 107 S. Ct. 1149 (1987). I. INTRODUCTION The fourth amendment to the United States Constitution pro- tects individuals against arbitrary and unreasonable searches and seizures. 1 Fourth amendment protection has repeatedly been found to include a general requirement of a warrant based on probable cause for any search or seizure by a law enforcement agent.2 How- ever, there exist a limited number of "specifically established and -

PDF Download a Skeleton Key to Twin Peaks

A SKELETON KEY TO TWIN PEAKS : ONE EXPERIENCE OF THE RETURN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK JB Minton | 422 pages | 28 Dec 2020 | Follow My Bliss Publishing | 9781732639119 | English | none A Skeleton Key To Twin Peaks : One Experience Of The Return PDF Book Powered by SailThru. Charlie 4 episodes, Carel Struycken Your country's customs office can offer more details, or visit eBay's page on international trade. Watch What Crappens. Opens image gallery Image not available Photos not available for this variation. Tommy 1 episode, Customer Reviews See All. Doctor Ben 1 episode, Thanks for telling us about the problem. Tom Paige 1 episode, Sophie 1 episode, When John and I sat down to start planning this new podcast, in which we will discuss themes of Twin Peaks The Return, he and I agreed on this theme for Episode 1 immediately. David Lynch has been accused for decades of sexism and even misogyny in his work, due largely to frequent depictions of violence against women. Farmer 1 episode, Travis Hammer Red's bodyguard uncredited unknown episodes. Trouble 1 episode, Alex Reyme Charlie 4 episodes, Keep Phoenix New Times Free However, I will not deny the author the right to have whatever theory he likes and I praise him for his excellent deductive skills, keen eye, and ability to forge connections I never thought of. Rebekah Del Rio 1 episode, The Red Room Podcast. The Veils 1 episode, This role is one she cannot escape, one with which she will forever be identified. You can help by participating in our "I Support" membership program, allowing us to keep covering Phoenix with no paywalls. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

Squash Courts, Wrestling Mats, and Fencing Strips on the Horizon Q&A

THE NATION'S OLDEST ON THE WEB: COUNTRY DAY SCHOOL www.pingry.org/ NEWSPAPER record VOLUME CXLII, NUMBER 1 The Pingry School, Basking Ridge, New Jersey OCTOBER 13, 2015 Squash Courts, Wrestling Mats, Q&A with New Dean That’sJake what you Ross remember the By ALLY PYNE (IV) AP: What are you most excited most, the connections you have At the end of September, I sat for? with people. and Fencing Strips on the Horizon down with the new Dean of Stu- JR: The whole thing. It’s fun dent Life, Mr. Jake Ross. Below, of having the groundbreaking excited for his fellow team being back with older students. AP: What would you say is the By HALEY PARK (VI) Mr. Ross shares his favorite Pingry ceremony. Mr. Bugliari then members and the promising There’s an energy that’s fantastic, biggest difference from when you memories, goals for the year and just in the last week. And I’m ex- were at school to now? After finally reaching 80% expressed his gratitude and for future of Pingry squash. advice for students. cited to be involved in more than JR: It’s tough to say any one being able to call Pingry home Mr. Ramsay Vehslage, head of the funds necessary to break just teaching. thing, but I think the biggest differ- ground, the much-anticipat- since 1942. coach of the varsity squash ence is just being on the other side ed athletics center has now Following the speakers’ re- team, was extremely excit- Ally Pyne: What would you AP: Is it true that you went to of the desk. -

Dara Wishingrad Res&Bio 042114

DARA WISHINGRAD Production Design Dara Wishingrad began her career in production design with the creation of massive 360º sets in live events for private affairs and corporate clients such as the Superbowl, The Ryder Cup, The US Open and PGA Golf Tournaments, Donna Karan and Laurence Fishburne. She was the production designer for the Directors Guild of America Honors and the Tribeca Film Festival, designing the public and private events and screening venues, most notably the General Motors "Tribeca Drive-In." In film, she was production designer on John Leguizamo’s upcoming original feature film, “Fugly!” based on his Broadway show “Ghetto Klown” and directed by Alfredo De Villa; Michael Urie’s metacomedy “He’s Way More Famous Than You”; Boaz Yakin’s (Remember The Titans) Sundance Film Festival featured independent film “Death In Love” starring Jacqueline Bisset, Josh Lucas, Lukas Haas and Adam Brody; “Certainty” directed by Peter Askin (Trumbo) written by Mike O’Malley and starring Valerie Harper, Giancarlo Esposito, Adelaide Clemens and Bobby Moynihan; Franc. Reyes' "The Ministers" a gritty New York drama starring John Leguizamo, Harvey Keitel and Florencia Lozano; Nia Vardalos’ (My Big Fat Greek Wedding) romantic comedy “I Hate Valentine’s Day” starring Nia, John Corbett, Rachel Dratch, Zoe Kazan; and many other films with notable directors and producers. Television credits include Premio Lo Nuestro 2001: The Latin Music International Awards and other commercial programming for Rainbow Media, Compulsive Pictures and the Univision Network. Dara originally trained in fine art at the San Francisco Art Institute and the Art Students League in New York. -

Reglas De Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe) a Book by Lydia Cabrera an English Translation from the Spanish

THE KONGO RULE: THE PALO MONTE MAYOMBE WISDOM SOCIETY (REGLAS DE CONGO: PALO MONTE MAYOMBE) A BOOK BY LYDIA CABRERA AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION FROM THE SPANISH Donato Fhunsu A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature (Comparative Literature). Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Inger S. B. Brodey Todd Ramón Ochoa Marsha S. Collins Tanya L. Shields Madeline G. Levine © 2016 Donato Fhunsu ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Donato Fhunsu: The Kongo Rule: The Palo Monte Mayombe Wisdom Society (Reglas de Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe) A Book by Lydia Cabrera An English Translation from the Spanish (Under the direction of Inger S. B. Brodey and Todd Ramón Ochoa) This dissertation is a critical analysis and annotated translation, from Spanish into English, of the book Reglas de Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe, by the Cuban anthropologist, artist, and writer Lydia Cabrera (1899-1991). Cabrera’s text is a hybrid ethnographic book of religion, slave narratives (oral history), and folklore (songs, poetry) that she devoted to a group of Afro-Cubans known as “los Congos de Cuba,” descendants of the Africans who were brought to the Caribbean island of Cuba during the trans-Atlantic Ocean African slave trade from the former Kongo Kingdom, which occupied the present-day southwestern part of Congo-Kinshasa, Congo-Brazzaville, Cabinda, and northern Angola. The Kongo Kingdom had formal contact with Christianity through the Kingdom of Portugal as early as the 1490s. -

Serial Historiography: Literature, Narrative History, and the Anxiety of Truth

SERIAL HISTORIOGRAPHY: LITERATURE, NARRATIVE HISTORY, AND THE ANXIETY OF TRUTH James Benjamin Bolling A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Minrose Gwin Jennifer Ho Megan Matchinske John McGowan Timothy Marr ©2016 James Benjamin Bolling ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Ben Bolling: Serial Historiography: Literature, Narrative History, and the Anxiety of Truth (Under the direction of Megan Matchinske) Dismissing history’s truths, Hayden White provocatively asserts that there is an “inexpugnable relativity” in every representation of the past. In the current dialogue between literary scholars and historical empiricists, postmodern theorists assert that narrative is enclosed, moribund, and impermeable to the fluid demands of history. My critical intervention frames history as a recursive, performative process through historical and critical analysis of the narrative function of seriality. Seriality, through the material distribution of texts in discrete components, gives rise to a constellation of entimed narrative strategies that provide a template for human experience. I argue that serial form is both fundamental to the project of history and intrinsically subjective. Rather than foreclosing the historiographic relevance of storytelling, my reading of serials from comic books to the fiction of William Faulkner foregrounds the possibilities of narrative to remain open, contingent, and responsive to the potential fortuities of historiography. In the post-9/11 literary and historical landscape, conceiving historiography as a serialized, performative enterprise controverts prevailing models of hermeneutic suspicion that dominate both literary and historiographic skepticism of narrative truth claims and revives an ethics responsive to the raucous demands of the past. -

Help Poland's Flood Victims

August / September 2010, Polish American News - Page 11 Museum’s Historic Reflections Project Part 5 September 13, 1964 - Rafal Ziemkiewicz (Born) Rafal Ziemkiewicz is known as a social science fiction author whose works deal with future governments and the political climate in Europe. He is also currently writing for the Polish edition of Newsweek. September 14, 1561 - Jan Tarnowski (Died) Jan Amor Tarnowski (1488–1561) was a Polish- Lithuanian szlachcic. He was Grand Crown Hetman from 1527 and was the founder of the city of Ternopil, where he built the Ternopil Castle and the Ternopil Lake. September 15, 1941 - Miroslaw Hermaszewski (Born) Miroslaw Hermaszewski is Poland’s first cosmonaut. In 1978, Hermaszewski spent eight days in the Salyut space station and won an award for his participation in the mission. He eventually made it to the rank of General of the Polish Air Force. Miroslaw Hermaszewski is currently retired. September 16, 1985 - Madeline Zima (Born) Madeline Rose Zima is an American actress, known Help Poland’s Flood Victims for her six years as Grace Sheffield on the TV Series The Nanny or more recently as Mia Cross on the The Polish American Congress Charitable Foundation (PACCF) is Showtime dramedy Californication. leading a drive to raise funds for the flood victims who have been stricken by the worst flooding to hit Poland since the late 19th century. Although southern Poland was the first area to experience September 17, 1968 - Jerzy Dabrowski (Died) severe flooding, the rivers have carried flood waters much further Jerzy Dabrowski was an aeronautical engineer and north. The Vistula River burst its banks in central Poland with designer of the famed PZL.37 Los medium bomber. -

Twin Peaks’ New Mode of Storytelling

ARTICLES PROPHETIC VISIONS, QUALITY SERIALS: TWIN PEAKS’ NEW MODE OF STORYTELLING MIKHAIL L. SKOPTSOV ABSTRACT Following the April 1990 debut of Twin Peaks on ABC, the TV’, while disguising instances of authorial manipulation evi- vision - a sequence of images that relates information of the dent within the texts as products of divine internal causality. narrative future or past – has become a staple of numerous As a result, all narrative events, no matter how coincidental or network, basic cable and premium cable serials, including inconsequential, become part of a grand design. Close exam- Buffy the Vampire Slayer(WB) , Battlestar Galactica (SyFy) and ination of Twin Peaks and Carnivàle will demonstrate how the Game of Thrones (HBO). This paper argues that Peaks in effect mode operates, why it is popular among modern storytellers had introduced a mode of storytelling called “visio-narrative,” and how it can elevate a show’s cultural status. which draws on ancient epic poetry by focusing on main char- acters that receive knowledge from enigmatic, god-like figures that control his world. Their visions disrupt linear storytelling, KEYWORDS allowing a series to embrace the formal aspects of the me- dium and create the impression that its disparate episodes Quality television; Carnivale; Twin Peaks; vision; coincidence, constitute a singular whole. This helps them qualify as ‘quality destiny. 39 SERIES VOLUME I, SPRING 2015: 39-50 DOI 10.6092/issn.2421-454X/5113 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF TV SERIAL NARRATIVES ISSN 2421-454X ARTICLES > MIKHAIL L. SKOPTSOV PROPHETIC VISIONS, QUALITY SERIALS: TWIN PEAKS’ NEW MODE OF STORYTELLING By the standards of traditional detective fiction, which ne- herself and possibly The Log Lady, are visionaries as well. -

The Portrayal of Tourette Syndrome in Film and Television Samantha Calder-Sprackman, Stephanie Sutherland, Asif Doja

ORIGINAL ARTICLE COPYRIGHT ©2014 T HE CANADIAN JOURNAL OF NEUROLOGICAL SCIENCES INC . The Portrayal of Tourette Syndrome in Film and Television Samantha Calder-Sprackman, Stephanie Sutherland, Asif Doja ABSTRACT: Objective: To determine the representation of Tourette Syndrome (TS) in fictional movies and television programs by investigating recurrent themes and depictions. Background: Television and film can be a source of information and misinformation about medical disorders. Tourette Syndrome has received attention in the popular media, but no studies have been done on the accuracy of the depiction of the disorder. Methods: International internet movie databases were searched using the terms “Tourette’s”, “Tourette’s Syndrome”, and “tics” to generate all movies, shorts, and television programs featuring a character or scene with TS or a person imitating TS. Using a grounded theory approach, we identified the types of characters, tics, and co-morbidities depicted as well as the overall representation of TS. Results: Thirty-seven television programs and films were reviewed dating from 1976 to 2010. Fictional movies and television shows gave overall misrepresentations of TS. Coprolalia was overrepresented as a tic manifestation, characters were depicted having autism spectrum disorder symptoms rather than TS, and physicians were portrayed as unsympathetic and only focusing on medical therapies. School and family relationships were frequently depicted as being negatively impacted by TS, leading to poor quality of life. Conclusions: Film and television are easily accessible resources for patients and the public that may influence their beliefs about TS. Physicians should be aware that TS is often inaccurately represented in television programs and film and acknowledge misrepresentations in order to counsel patients accordingly. -

2010 Annual Report

2010 ANNUAL REPORT Table of Contents Letter from the President & CEO ......................................................................................................................5 About The Paley Center for Media ................................................................................................................... 7 Board Lists Board of Trustees ........................................................................................................................................8 Los Angeles Board of Governors ................................................................................................................ 10 Media Council Board of Governors ..............................................................................................................12 Public Programs Media As Community Events ......................................................................................................................14 INSIDEMEDIA Events .................................................................................................................................14 PALEYDOCFEST ......................................................................................................................................20 PALEYFEST: Fall TV Preview Parties ...........................................................................................................21 PALEYFEST: William S. Paley Television Festival ......................................................................................... 22 Robert M.