Freshwater Mussels of the Mackinaw River

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NATURAL ENVIRONMENT Natural Resources Are Positive Components of Any De- Velopment and Add Value Where Integrated Appropri- Ately Into Development Projects

8 NATURAL ENVIRONMENT Natural resources are positive components of any de- velopment and add value where integrated appropri- ately into development projects. This harmonious coexistence begins with a good understanding of our natural environment. This chapter will examine topics such as air quality, water resources, energy resources, floodplains, stream bank erosion, local food and urban gardening. It will also identify the potential environmental concerns or threats such as gas pipelines and hydraulic fracturing.DRAFT 117 KEY FINDINGS Bloomington faces two challenges in managing the public water sup- As calculated by the Ecology Action Center, as of 2008 residents of ply. The short-term need is to mitigate the effects of high nitrate lev- Bloomington accounted for 31% of greenhouse gas emissions pro- els in Lake Bloomington. This requires reducing nitrate infiltration duced by electricity use. 61% of emissions were from commercial from watershed and agricultural runoff, and ongoing improvements users, 5% from industry, and 3% from local government use of elec- to water treatment systems. The long-term challenge is adding public tricity. Private sector users produce nearly all emissions caused by water supply sources to meet the need of a growing community, by transportation. preserving current resources and identifying new sources for water. The McLean County Landfill #2 is scheduled for a 2017 closure upon The growth of the City of Bloomington has often been achieved by reaching its capacity of nearly 4 million cubic yards. Annual volume converting farmland into new development. Historically, the City in the landfill has been 90,000 tons, equaling 300 tons per day. -

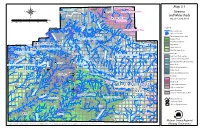

Map 3.1 Streams and Watersheds

k e e r Upper Vermilion River C Map 3.1 s Weston Panther Creek Meadows k Gridley o o El Paso Chenoa R North Fork Vermilion River Streams ® and Watersheds V e r m ii ll ii o n McLean County, Illinois Miles Rooks Creek T 0 1.25 2.5 5 7.5 10 u r k e y C r k e e e re k Legend C ck u South Fork Vermilion River B Rivers and Streams S ix Lakes and Detention M Lexington i le Salt Creek/Upper Sangamon River Basin C r ee k Buck Creek-Mackinaw River Kickapoo Creek Pleasant Hill North Fork Salt Creek Cropsey R Hudson H ock M a c k ii n a w enline Creek Sugar Creek Creek Upper Salt Creek Carlock Sixmile Creek-Mackinaw River West Fork Sugar Creek k e Mud Creek-Mackinaw River e ver r Colfax Mackinaw Ri C Anchor Mackinaw River Basin Towanda d e Henline Creek-Mackinaw River k o Buck Creek-Mackinaw River o ek r re M C r C on Cooksville Henline Creek-Mackinaw River uga ey C k S ree For k est Danvers Little Mackinaw River-Mackinaw River W eek Normal ll Cr Money Creek s Mi Money Creek Little Mackinaw River-Mackinaw River King Merna Mud Creek-Mackinaw River West Fork Sugar Creek Panther Creek Sixmile Creek-Mackinaw River Bloomington Vermilion RIver Basin San North Fork Vermilion River gamon Holder River Arrowsmith Rooks Creek Covell Ellsworth Stanford U p p e r S a n g a m o n South Fork Vermilion River Drummer Creek-Sangamon River Saybrook Upper Vermilion River ek Upper Sangamon River Basin re Shirley Gillum C S a l t r S a l t Drummer Creek-Sangamon River ga u S Kickapoo Creek eek Downs er Cr Timb Sugar Creek North Fork Salt Creek Upper Salt Creek Roads and Streets Incorporated Areas McLean County boundary Leroy Bellflower ek re C lt P a r S McLean a Heyworth i k r r i o e F k e C th e r r r e o C e N t k Osman l a S McLean County Regional Data Sources: River basin and watershed data from National Resources Conservation Service of the U.S. -

(Mollusca: Bivalvia: Unionidae) of the Mackinaw River in Illinois

THE FRESHWATER MUSSELS (MOLLUSCA : BIVALVIA : UNIONIDAE) OF THE MACKINAW RIVER IN ILLINOIS FINAL REPORT 12 February 1988 )n,--3 Kevin S. Cummings, Christine A . Mayer & Lawrence M . Page Illinois Natural History Survey 607 East Peabody Drive Champaign, Illinois 61820 Prepared for Illinois Department of Conservation Division of Natural Heritage 524 South Second Street Springfield, Illinois 62706 Section of Faunistic Surveys and Insect Identification Technical Report 1988 (3) TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE LIST OF FIGURES in LIST OF TABLES iv LIST OF APPENDICES v INTRODUCTION 1 METHODS 3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION 3 SPECIES ACCOUNTS 11 Proposed State Endangered Species 11 Proposed State Threatened Species 12 Other Species 12 Introduced Species 18 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 18 LITERATURE CITED 19 LIST OF FIGURES PAGE Figure 1 . Collection sites in the Mackinaw River drainage, 1987 4 Figure 2. Shaded region of drainage represents area to be inundated by construction of proposed dam 6 iii LIST OF TABLES PAGE Tablet . Comparison of the number of species of unionid mussels collected from the Mackinaw River drainage during past studies 2 Table 2 . Location of collection sites in the Mackinaw River, 1987 5 Table 3 . Site by site listing of all mussel species collected in the Mackinaw River, 1987 8 Table 4 . Numbers, relative abundance, and percent composition of mussels collected in the Mackinaw River, 1987 9 Table 5 . A comparison of the number of mussels collected per man-hour in midwestern stream surveys (1981-1988) 10 iv LIST OF APPENDICES PAGE Appendix I. Collection sites of Max R . Matteson 1948-1957 21 Appendix II. Illinois State Museum Records 1955-1966 23 Appendix Ill . -

Mackinaw River Watershed Total Maximum Daily Load

Mackinaw River Watershed Total Maximum Daily Load DRAFT Stage 1 Report 1021 North Grand Avenue East P.O. Box 19276 Springfield, Illinois 62794-9276 Report Prepared by: November 2018 Mackinaw River Watershed TMDL Draft Stage 1 Report Contents Figures ........................................................................................................................................................ iii Tables .......................................................................................................................................................... iii Acronyms and Abbreviations ................................................................................................................... iv 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Water Quality Impairments .......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 TMDL Endpoints .......................................................................................................................... 4 1.2.1 Designated Uses .................................................................................................................. 4 1.2.2 Water Quality Standards and TMDL Endpoints ................................................................. 4 2. Watershed Characterization ......................................................................................................... 8 2.1 Jurisdictions -

Geology of the Mackinaw River Watershed, Mclean, Woodford, and Tazewell Counties, Illinois

Geology of the Mackinaw River Watershed, McLean, Woodford, and Tazewell Counties, Illinois C. Pius Weibel and Robert S. Nelson Geological Science Field Trip Guidebook 2009A April 18, 2009 May 2, 2009 Institute of Natural Resource Sustainability ILLINOIS STATE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Cover photograph: View of the Mackinaw River (photograph by W.T. Frankie). Acknowledgment The information in the first part of this guidebook is adapted from ISGS FieldTrip Guidebook 2004A, Guide to the Geology of the Pekin Area, Tazwell and Mason Counties, Illinois, by Wayne T. Frankie, Russell Jacobson, and Robert S. Nelson. Geological Science Field Trips The Illinois State Geological Survey (ISGS) conducts four tours each year to acquaint the public with the rocks, mineral resources, and landscapes of various regions of the state and the geological processes that have led to their origin. Each trip is an all-day excursion through one or more Illinois counties. Frequent stops are made to explore interesting phenomena, explain the processes that shape our environment, discuss principles of earth science, and collect rocks and fossils. People of all ages and interests are welcome. The trips are especially helpful to teachers who prepare earth science units. Grade school students are welcome, but each must be accompanied by a parent or guardian. High school science classes should be supervised by at least one adult for every ten students. The inside back cover shows a list of guidebooks of earlier field trips. Guidebooks may be obtained by con- tacting the Illinois State Geological Survey, Natural Resources Building, 615 East Peabody Drive, Cham- paign, IL 61820-6964 (telephone: 217-244-2414 or 217-333-4747). -

Freshwater Mussels of the Mackinaw River

Freshwater Mussels of the Mackinaw River Alison L. Price, Diane K. Shasteen, Sarah A. Bales INHS Technical Report 2011 (45) Prepared for: Illinois Department of Natural Resources: Office of Resource Conservation U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Illinois Natural History Survey Issued December 16, 2011 Prairie Research Institute, University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign William Shilts, Executive Director Illinois Natural History Survey Brian D. Anderson, Director 1816 South Oak Street Champaign, IL 61820 217-333-6830 Freshwater Mussels of the Mackinaw River 2011 Illinois Natural History Survey, University of Illinois, Prairie Research Institute Illinois Department of Natural Resources Alison Price, Diane Shasteen, Sarah Bales Preface While broad geographic information is available on the distribution and abundance of mussels in Illinois, systematically collected mussel-community data sets required to integrate mussels into aquatic community assessments do not exist. In 2009, a project funded by a US Fish and Wildlife Service State Wildlife Grant was undertaken to survey and assess the freshwater mussel populations at wadeable sites from 33 stream basins in conjunction with the Illinois Department of Natural Resources (IDNR)/Illinois Environmental Protection Agency (IEPA) basin surveys. Inclusion of mussels into these basin surveys contributes to the comprehensive basin monitoring programs that include water and sediment chemistry, instream habitat, macroinvertebrate, and fish, which reflect a broad spectrum of abiotic and biotic stream resources. These mussel surveys will provide reliable and repeatable techniques for assessing the freshwater mussel community in sampled streams. These surveys also provide data for future monitoring of freshwater mussel populations on a local, regional, and watershed basis. Agency Contacts Kevin S. -

The Mackinaw River

The Mackinaw River Location: The Mackinaw River originates in Ford County near Sibley, and flows in a westerly direction for 130 miles before joining the Illinois River downstream of Pekin. The associated watershed is an area of 1,138 square miles, and covers parts of 6 central Illinois counties. The majority of the river is in McLean, Woodford, and Tazewell counties, with the river flowing through only a few cities or towns, such as Colfax, Lexington, Goodfield, and Mackinaw. Characteristics: The Mackinaw River begins as a drainage ditch near Sibley, and begins to meander near Colfax, where a thin band of trees begin. Trees line most of the banks of the river all of the way to the Illinois River, with larger forests found in the middle reaches with frequent gaps due to agricultural fields. The Mackinaw varies in depth from 1-6 feet and has an average width of 70 feet. The water level is extremely variable, with frequent flooding in the spring, and is very nearly dry during times of prolonged drought. Major tributaries include Henline Creek,Turkey Creek, Money Creek, Sixmile Creek, Wolf Creek, Denman Creek, Panther Creek, Walnut Creek, Rock Creek, Mud Creek, Prairie Creek, Little Mackinaw Creek, Dillon Creed, and Hickory Grove Ditch. The Biological Stream Characterization rated all segments of Henline, Panther, and Walnut Creeks and the Mackinaw River from Denman Creek to Mud Creek, and upstream from Money Creek as “A” streams, Unique Aquatic Resource (the highest ranking possible). Two segments of the Mackinaw are recognized as Biologically Significant Streams due to the fish and mussel diversity. -

Tazewell County Yearbook

Tazewell County 2021 YEARBOOK John C. Ackerman County Clerk And Recorder REFERENCE GUIDE Tazewell County, Illinois YEARBOOK 2021 Containing a list of Illinois Executive and Judicial Officials, County Employees and Officials, Township Officials, and other information pertinent to Tazewell County. BRAND NEW WEBSITE Created by the Tazewell County Clerk’s Office and the GIS Department. FIND YOUR ELECTED OFFICIAL: U.S HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ILLINOIS HOUSE REPRESENTATIVE ILLINOIS STATE SENATE COUNTY OFFICIALS CITY OFFICIALS Go to: www.tazewell.com CLICK ON “HOW DO I…?”. CLICK ON “FIND MY ELECTED OFFICIAL” Vital Stats: (309) 477-2264 TAZEWELL COUNTY CLERK / RECORDER Elections: (309) 477-2267 Recorders: (309) 477-2210 JOHN C. ACKERMAN Print Shop:(309) 477-2733 11 SOUTH 4TH STREET / SUITE 203 & 124 / PEKIN, IL 61554 4/30/2021 On behalf of all the office staff at the Tazewell County Clerk & Recorder of Deeds Office, I am proud to present to you the 2021 Tazewell County Yearbook. This directory is an important tool in assisting our citizens with the ability to communicate with their elected officials. This 2021 Tazewell County Yearbook was transcribed by Tazewell County Deputy Clerk Katie Gazelle and printed by Tazewell County Clerk Print Shop Manager Gayle Williams. New to this 2021 Tazewell County Yearbook are several pages dedicated to a brief history of Tazewell County. This section was standard in earlier Tazewell County Yearbooks, but had not been included since 1981. This new Tazewell County History Section includes the settlement of the county, several historical first within the county, county boundaries, county government structure, county government buildings, and other points of interest. -

Sand and Gravel Resources of Tazewell County, Illinois

STATE OF ILLINOIS DEPARTMENT OF REGISTRATION AND EDUCATION SAND AND GRAVEL RESOURCES OF TAZEWELL COUNTY, ILLINOIS Ralph E. Hunter ILLINOIS STATE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY John C. Frye, Chief URBANA CIRCULAR 399 • 1966 llllli[llmilli[~~~i~~n~~~~~~3 3051 00004 0000 1111 SAND AND GRAVEL RESOURCES OF TAZEWELL COUNTY, ILLINOIS Ralph E. Hunter ABSTRACT Tazewell County has large amounts of sand and gravel, most of which were deposited by meltwater from glaciers during the Pleistocene Epoch or Ice Age. These deposits are found principally in valleys that served as major channels for the meltwater, in the vicinity of the Il linois River, Mackinaw River, and Farm Creek. Smaller amounts are found in deposits from glacial meltwater away from these streams, in sand dunes, and in stream alluvium. Geographical locations of the deposits have been mapped on the scale 1:62, 500. INTRODUCTION Purpose of Study Increasing amounts of sand and gravel are required for construction in the growing urban areas of Illinois and for improvement of the state highway network. In response to the need for information regarding these resources, the Illinois State Geological Survey is engaged in a program to evaluate or, in places, re evaluate the sand and gravel resources of the state. This report, covering Taze well County (fig. 1), is a part of that program. Pekin and East Peoria, and their §iuburbs, cover extensive sand and gravel deposits, which therefore are unavailable for commercial exploitation. As these cities continue to grow, resources remaining in the county will become increasingly important as reserves to supply the needs of the area. -

Mackinaw River Subwatershed Management Plan Little Mackinaw River Printed January 2000

Mackinaw River Project Mackinaw River Subwatershed Management Plan Little Mackinaw River Printed January 2000 Prepared by: Deborah Forester The Nature Conservancy Approved by: Mackinaw River Watershed Council Prepared for: Financial Assistance Agreement Number 95-01 Illinois Environmental Protection Agency Division of Water Pollution Control 1021 North Grand Avenue East, P.O. Box 19276 Springfield, Illinois 62794-9276 This report was prepared using U.S. Environmental Protection Agency funds under Section 319 of the Clean Water Act distributed through the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency. The findings and recommendations herein are not necessarily those of the funding agencies. Mackinaw River Subwatershed Management Plan – Little Mackinaw River Table of Contents Component #1, Mission Statement .................................................. 1 Component #2, Watershed Description ........................................... 1 Component #3, Watershed Activities ............................................... 1 Component #4, Watershed Resource Inventory ............................. 3 Waterbodies ............................................................................... 3 Designated Use .......................................................................... 6 Impairments ............................................................................... 7 Groundwater .............................................................................. 9 Irrigation .................................................................................. -

Wagonseller Road Bridge Feasibility Report MDM Edits.Docx

Mackinaw River, Tazewell County Illinois Continuing Authorities Program Section 14 Emergency Streambank Protection Wagonseller Road Bridge Feasibility Report and Integrated Environmental Assessment Doc Version: Draft Feasibility Report November 2018 This information is distributed solely for the purpose of pre-dissemination review under applicable information quality guidelines. It has not been formally disseminated by USACE. It does not represent and many not be construed to represent any agency determination or policy. Mackinaw River, Tazewell County Illinois Continuing Authorities Program Section 14 Emergency Streambank Protection Wagonseller Road Bridge Feasibility Report and Integrated Environmental Assessment TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Purpose of the Report ........................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Project Location .................................................................................................................. 1 1.3 Project Authority and Scope ............................................................................................... 2 1.4 Problems, Opportunities, Objectives, and Constraints ...................................................... 3 1.4.1 Problems .............................................................................................................. 3 1.4.2 Opportunities ...................................................................................................... -

Hydrogeology and Ground-Water Avail., SW Mclean and SE Tazwell CO, Part 2 Aquifer Model

Coop 19 Hydrogeology and Ground-Water Availability in Southwest McLean and Southeast Tazewell Counties Part 2: Aquifer Modeling and Final Report 1998 Cooperative Ground-Water Report 19 Department of Natural Resources ILLINOIS STATE WATER SURVEY ILLINOIS STATE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Hydrogeology and Ground-Water Availability in Southwest McLean and Southeast Tazewell Counties Part 2: Aquifer Modeling and Final Report Steven D. Wilson George S. Roadcap Beverly L. Herzog David R. Larson Derek Winstanley Title: Hydrogeology and Ground-Water Availability in Southwest McLean and Southeast Tazewell Counties, Part 2: Aquifer Modeling and Final Report Abstract: An assessment of the aquifer characteristics and ground-water availability has been completed for one of the largest sand-and-gravel aquifers in Illinois, the Sankoty-Mahomet Sand aquifer, in the confluence area of the Mahomet and Mackinaw Bedrock Valleys in McLean and Tazewell Counties. Based on data gathered during the field portion of the study, a ground-water flow model was developed that simulates the effects of a hypothetical well field for various locations within the study area. It was used to estimate the quantity of ground water that could be withdrawn from the aquifer within the study area. The model was calibrated to match water levels measured in area wells in 1994 and to match the baseflow gains and losses in the Mackinaw River and Sugar Creek. A hypothetical well field, pumping 15 million gallons a day (mgd), was simulated at four locations, The results varied from a maximum drawdown of 8 feet in the Hopedale scenario to 55 feet in the Armington scenario. If a well field similar to the well fields modeled were installed in the study area, as many as 400 private wells may be impacted.