HERNANDEZ-THESIS.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bachelor Alum Melissa Rycroft Strickland Delivers a Girl

Bachelor Alum Melissa Rycroft Strickland Delivers a Girl It’s a girl for Bachelor alum Melissa Rycroft Strickland, reports People. She and husband Tye Strickland welcomed daughter Ava Grace Strickland on Wednesday afternoon. Rycroft, who dumped Jason Mesnick after accepting a proposal on the Bachelor, married Strickland in December 2009. Ava Grace, the first child for both, weighed in at 6 lbs. 13 oz. and was born in Dallas, Texas. Rycroft’s reaction? “Everything is wonderful and life is exactly as it should be.” How do you keep hope after a relationship ends badly? Cupid’s Advice: There can be few things more mind boggling than believing your relationship is fine one day and then finding yourself single the next. This little doozey makes us all a bit crazy. Even if you think you’re ready for a new relationship, it can be hard to approach it with a clean slate: 1. Time heals all: This may be true, but so does moving forward. Don’t hold yourself back and swear off relationships just because one didn’t work out. Each relationship is different and should be treated as such. 2. Learn from your mistakes: Your relationship may be over, but it’s not all bad. Treat it as an opportunity to learn from the past and move on to a happier place in a new relationship. 3. Look for the silver lining: If all else fails and skies look gray ahead, keep it simple. If you were meant to be together, you would be. Keep the faith that there’s someone out there for you.. -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. Adam Ant=English musician who gained popularity as the Amy Adams=Actress, singer=134,576=68 AA lead singer of New Wave/post-punk group Adam and the Amy Acuff=Athletics (sport) competitor=34,965=270 Ants=70,455=40 Allison Adler=Television producer=151,413=58 Aljur Abrenica=Actor, singer, guitarist=65,045=46 Anouk Aimée=Actress=36,527=261 Atif Aslam=Pakistani pop singer and film actor=35,066=80 Azra Akin=Model and actress=67,136=143 Andre Agassi=American tennis player=26,880=103 Asa Akira=Pornographic act ress=66,356=144 Anthony Andrews=Actor=10,472=233 Aleisha Allen=American actress=55,110=171 Aaron Ashmore=Actor=10,483=232 Absolutely Amber=American, Model=32,149=287 Armand Assante=Actor=14,175=170 Alessandra Ambrosio=Brazilian model=447,340=15 Alan Autry=American, Actor=26,187=104 Alexis Amore=American pornographic actress=42,795=228 Andrea Anders=American, Actress=61,421=155 Alison Angel=American, Pornstar=642,060=6 COMPLETEandLEFT Aracely Arámbula=Mexican, Actress=73,760=136 Anne Archer=Film, television actress=50,785=182 AA,Abigail Adams AA,Adam Arkin Asia Argento=Actress, film director=85,193=110 AA,Alan Alda Alison Armitage=English, Swimming=31,118=299 AA,Alan Arkin Ariadne Artiles=Spanish, Model=31,652=291 AA,Alan Autry Anara Atanes=English, Model=55,112=170 AA,Alvin Ailey ……………. AA,Amedeo Avogadro ACTION ACTION AA,Amy Adams AA,Andre Agasi ALY & AJ AA,Andre Agassi ANDREW ALLEN AA,Anouk Aimée ANGELA AMMONS AA,Ansel Adams ASAF AVIDAN AA,Army Archerd ASKING ALEXANDRIA AA,Art Alexakis AA,Arthur Ashe ATTACK ATTACK! AA,Ashley -

Pop Culture Trivia Questions Xxii

POP CULTURE TRIVIA QUESTIONS XXII ( www.TriviaChamp.com ) 1> American versions of British shows usually fail because they file off the rough edges of the originals. But which of these American shows inspired a failed British version called "Days Like These"? a. That 70s Show b. Cheers c. All in the Family d. Happy Days 2> Designed by visual-effects guru Robert Mattey, the three mechanical sharks used in Jaws were collectively called Bruce, in honor of Bruce Ramer, who was which director's lawyer? a. George Lucas b. John Cameron c. Steven Spielberg d. Sam Raimi 3> Oscar-winner Shirley Jones starred with her real-life stepson David Cassidy on what TV show, modeled on the real-life family called the Cowsills? a. The Monkees b. The Brady Bunch c. The Partridge Family d. The A-Team 4> In the 2004 film, Harold Lee and Kumar Patel spend the night trying to satisfy their stoner craving for what chain's burgers? a. In and Out b. Fatburger c. White Castle d. Fuddruckers 5> On what TV show were the leads replaced by their cousins, Coy and Vance? a. Wings b. Starsky and Hutch c. The Dukes of Hazzard d. Law and Order 6> Tony Danza's pro record as a boxer was four wins and three losses. And he later played a boxer on what show? a. Taxi b. Who's the Boss c. Cheers d. Hill Street Blues 7> Huey, Dewey and Louie aren't Donald's kids. They're his nephews. Who was their mother? a. Dumbella Duck b. -

LSHA May Be Looking to Sell

1 TUESDAY, OCTOBER 15, 2013 | YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1874 | 75¢ Lake City Reporter LAKECITYREPORTER.COM LSHA may be looking to sell in order to remove the burden of funding people of Columbia County, be on indigent care. If the Affordable Care Hospital authority says indigent care from the taxpayers. and we’re not elected. ... Act works the way it should, everyone should it will consider seeking The authority did not make any decisions It’s time that we get out of be covered by an insurance agency. about the sale during its October meeting, the business.” “I think the time has arrived in the medi- a buyer for Lake Shore. but did suggest bringing in a consultant to Currently, the Hospital cal industry for the taxpayers to seriously By AMANDA WILLIAMSON discuss how to handle the process. Authority covers the care consider getting out of the healthcare busi- [email protected] “I think that the hospital authority has for indigent patients at ness,” Barry said. “With the purchase of really outlived its usefulness,” said author- Berry Shands Lake Shore Regional HMA to CHS coming up the first quarter As the Affordable Care Act moves onto ity member Koby Adams. “When I had my Medical Center. But as the of the year, I think this board needs to take the health care scene, the Lake Shore interview with the governor, he asked me new health care act takes effect, Lake Shore a serious thought about attempting to sell Hospital Authority entertained the idea what I didn’t like about the authority. -

Against the Wind City Attorney’S Tornado Damage Is Last Straw for Stanchfi Eld Woman Resignation

FREE Hearing is about ISANTI-CHISAGOISANTI-CHISAGO connecting with people. (763) 444-4051 THURSDAY, JULY 30, 2020 VOL. 114 NO. 31 COUNTYSTAR.COM PRIMARY CONCERN: Cambridge Council candidates featured ahead of Aug. 11 election. PAGE 10-11 Against the wind City attorney’s Tornado damage is last straw for Stanchfi eld woman resignation BY LORI ZABEL [email protected] letters to be Jilly Arnoldy was relaxing in bed watching an episode of “Perry Mason” just after 1 a.m. on Saturday, July 18, made public when she heard the wind suddenly pick up outside. She switched to anoth- BY BILL STICKELS III er channel to fi nd a news report that [email protected] her Stanchfi eld Township home on 389th Avenue just west of Highway 65 When it was announced during a was under a tornado warning. special North Branch City Council Within moments, the weatherman’s meeting on July 6 that Patrick Dor- voice cut out and the house went dark an had resigned from his position as at 1:03 a.m. as an EF-1 tornado bore city attorney, it was done so without down on the property. the inclusion of the letter of resigna- Arnoldy grabbed her three small tion in the meeting packet, leaving dogs and escaped her south-facing the reasons for this change to spec- bedroom to shelter in an inner hall- ulation. Following the July 28 City way. She waited for the “freight train” Council meeting, however, those sound and didn’t hear it, but her ears reasons - along with perhaps other popped with the change in air pres- “behind-the-scenes” information - sure. -

'Bachelor Pad 2' Recap Episode 2: Ames Brown

‘Bachelor Pad 2’ Recap Episode 2: Ames Brown Trumps them All By Lori Bizzoco Usually when a former Bachelor or Bachelorette leaves the show voluntarily, like two-time ‘Bachelor Pad’ contestant and swimsuit model, Gia Allemand did last night, it becomes the episode news headliner the next day. But last night’s storybook ending even knocked out coverage of the attention- seeking love triangle usually reserved for Jake Pavelka, Vienna Girardi and Kasey Kahl. It was a scene that leaves us understanding why even bad reality shows are beating out long- standing soap operas. You can’t make this stuff up! Last night there were two scenes that made single women everywhere believe in love again. First was the closing scene with Ivy-League, world-traveling, portfolio manager, Ames Brown. After he said a heartfelt good-bye to his newfound love and eliminated housemate, Jackie Gordon he turned around to head back towards the house. What happened next made hearts stop everywhere. Instead of continuing his walk toward the contestants, Ames slowly stopped, raised his hand and waved good-bye to them. Giving up the $250,000 prize, he sprinted back towards the limousine with Jackie inside. That fairy-tale exit trumped everything else on the show and gives romance fanatics a reason to believe that Mr. Right is a possibility, especially if you go after the awkwardly smart, rich guy wearing the hot pink pants. In Ames’ own words, “This is the happiest limo ride in Bachelor history.” The second love scene comes with ex’s, Michael Stagliano and children’s book author, Holly Durst. -

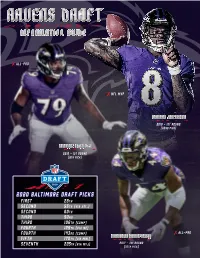

Information Guide

INFORMATION GUIDE 7 ALL-PRO 7 NFL MVP LAMAR JACKSON 2018 - 1ST ROUND (32ND PICK) RONNIE STANLEY 2016 - 1ST ROUND (6TH PICK) 2020 BALTIMORE DRAFT PICKS FIRST 28TH SECOND 55TH (VIA ATL.) SECOND 60TH THIRD 92ND THIRD 106TH (COMP) FOURTH 129TH (VIA NE) FOURTH 143RD (COMP) 7 ALL-PRO MARLON HUMPHREY FIFTH 170TH (VIA MIN.) SEVENTH 225TH (VIA NYJ) 2017 - 1ST ROUND (16TH PICK) 2020 RAVENS DRAFT GUIDE “[The Draft] is the lifeblood of this Ozzie Newsome organization, and we take it very Executive Vice President seriously. We try to make it a science, 25th Season w/ Ravens we really do. But in the end, it’s probably more of an art than a science. There’s a lot of nuance involved. It’s Joe Hortiz a big-picture thing. It’s a lot of bits and Director of Player Personnel pieces of information. It’s gut instinct. 23rd Season w/ Ravens It’s experience, which I think is really, really important.” Eric DeCosta George Kokinis Executive VP & General Manager Director of Player Personnel 25th Season w/ Ravens, 2nd as EVP/GM 24th Season w/ Ravens Pat Moriarty Brandon Berning Bobby Vega “Q” Attenoukon Sarah Mallepalle Sr. VP of Football Operations MW/SW Area Scout East Area Scout Player Personnel Assistant Player Personnel Analyst Vincent Newsome David Blackburn Kevin Weidl Patrick McDonough Derrick Yam Sr. Player Personnel Exec. West Area Scout SE/SW Area Scout Player Personnel Assistant Quantitative Analyst Nick Matteo Joey Cleary Corey Frazier Chas Stallard Director of Football Admin. Northeast Area Scout Pro Scout Player Personnel Assistant David McDonald Dwaune Jones Patrick Williams Jenn Werner Dir. -

Arbiter, February 24 Students of Boise State University

Boise State University ScholarWorks Student Newspapers (UP 4.15) University Documents 2-24-2005 Arbiter, February 24 Students of Boise State University Although this file was scanned from the highest-quality microfilm held by Boise State University, it reveals the limitations of the source microfilm. It is possible to perform a text search of much of this material; however, there are sections where the source microfilm was too faint or unreadable to allow for text scanning. For assistance with this collection of student newspapers, please contact Special Collections and Archives at [email protected]. tHU /I 5 0 R Y FE 8R U·R R Y i! ~ aD 0 5 THE 'NO E P Ell DE III 5 T U 0 E II T V 0 ICE 0 F B 0 I 5 E 5 T R TE 5' NeE 1 9 3 3 VOLUME 17 FI II 5T '.5 5 UE FREE ISSUE 'IS READ US ONLINE AT Hoods thrash ) message boards, breaking news, archive search, photo Boise altdeshnws & weather ~enate..impeache.s Morriss I ! . President accused of appointing himself lobbyist I BY G A EG OilY AU TT Y . ASBSU president to make the appropriate Sen. Joe Holladay said he was tipped off allegations and confirmed that Morriss had in fact received the service I News Edrtnr appointment and did not think twice about about Morriss' self-appointment by an ASBSU award. Morriss' appointment of himself, saying, "we adviser the week of Feb; 13. On. Feb. 15, an "It's been a long 48 hours, an emotional 48 hours," Labrecque said. -

‘Bachelor in Paradise’ Star Chris Bukowski on Celebrity Romance with Elise Mosca: Dates Were “Spec

‘Bachelor In Paradise’ Star Chris Bukowski on Celebrity Romance with Elise Mosca: Dates Were “Spectacular” Interview by Whitney Johnson. Written by Sarah Batcheller and Shannon Seibert. Bartlett, Illinois native Chris Bukowski was the fourth runner-up on Emily Maynard’s season ofThe Bachelorette and was seen as a main competitor on season 3 of the Bachelor Pad. Since his initial reality TV appearance, he has molded himself into quite the entrepreneur as the owner of The Bracket Room, a sports bar and lounge in Arlington, Virginia. Earlier this summer though, Bukowski put his business on the back burner and returned to the small screen with the hope of finding a celebrity romance on Bachelor in Paradise (fourth time’s a charm, right?). Chris Bukowski on Looking for Relationship and Love on Reality TV Related Link: ‘Bachelorette’ Star Marcus Grodd Is Engaged to ‘Bachelor in Paradise’ Costar He recently created quite a media frenzy when he “crashed” the premiere episode of Andi Dorfman’s season of The Bachelorette. We saw on the Men Tell All episode that host Chris Harrison wouldn’t let Bukowski come to the stage and meet her. “I was totally thrown off-guard when Chris said something to me — I wasn’t miked or anything. He kind of bombarded me!” he shares in our exclusive celebrity interview. Still, he says that final pick Josh Murray “seems like a good guy for Andi.” When he got the call for Bachelor in Paradise, it was no surprise that he was open to the experience. “The producers approached me about it, and I figured, ‘Why not?’ I was able to take time off from the restaurant, so it worked out really well in that sense. -

Playing Bachelor: Playboy's 1950S and 1960S Remasculinization

Playing Bachelor: Playboy’s 1950s and 1960s Remasculinization Campaign A Research Paper Prepared By Alison Helget Presented To Professor Marquess In Partial Fulfillment for Historical Methods 379 November 06, 2019 2 Robert L. Green’s 1960 article “The Contemporary Look in Campus Classics”, adheres to manifestation of the ‘swinging bachelor’ and his movement into professionalism. A college student’s passage from a fraternal environment of higher education to the business world demands an attitude and clothing makeover. Playboy presents the ideal man employers plan to hire. However, a prideful yet optimistic bravado exemplifies these applicants otherwise unattainable without the magazine’s supervision. Presented with a new manliness, American males exhibited a wider range of talents and sensitivity towards previously feminine topics. In accordance with a stylistic, post-schoolboy decadence, the fifties and sixties questioned gender appropriation, especially the hostile restrictions of the average man.1 Masculinity shapes one’s interactions, responding to global events as an agency of social relationships. Answering the call of World War II, men rushed to the service of nationalism. The homecoming from Europe forced the transition from aggressiveness to domestic tranquility, contradicting the macho training American soldiers endured. James Gilbert explores the stereotypes imposed upon middle-class men as they evolved alongside urbanity and the alterations of manliness apparent in the public sector. However, the Cold War threatened the livelihoods of men and their patriarchal hierarchy as the exploration of gender just emerged. In Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era, Elaine Tyler May notes the emphasis on family security amidst heightened criticism and modification, clearly noting masculinity’s struggle with the intervention of femininity and socio-economic restructuring. -

October Artabout

Thursday, October 5, 2017 DAILYDEMOCRAT.COM FACEBOOK.COM/DAILYDEMOCRAT @WOODLANDNEWS DAILY DEMOCRAT Jackie Leonardo at herSpace (123E St., Suite 330) OCTOBER ARTABOUT Two new venues — herSpace and Three Ladies Café — welcomed to the Second Friday ArtAbout this month. PAGE 2 COURTESY YOUR SOURCE FOR LOCAL ARTS AND ENTERTAINMENT LOCAL DINING& ENTERTAINMENT LISTINGS | LOCAL EVENTS TO LIVEN YOUR WEEKEND | LOCAL CELEBRATIONS | LOCAL TV LISTINGS 2 | E A+E | DAILYDEMOCRAT.COM OCTOBER 5- 11, 2017 DAVIS New venues featured at October ArtAbout Lauren James Special to The Democrat October’s ArtAbout wel- comes two new venues — herSpace and Three Ladies Café — to the Second Fri- day ArtAbout this month. Also, this month local residents are invited to come out to participate in the city of Davis and Yolo Hospice collaboration to bring “Before I Die …” to the Davis community for October’s ArtABout. This public wall has been pro- duced more than 2,000 times in 70 countries, and presented in 35 languages. John Natsoulas Gallery is joining October’s ArtAbout with their 10th Annual Da- vis Jazz and Beat Festival: The Ultimate Music, Art and Poetry Collaboration; a collaboration between poets, jazz musicians and painters. Those are just a few highlights of this Monica Jurik at Symphony Financial Planning (416F St.) month’s ArtAbout! Davis Downtown’s 2nd want to …” Everyone is in- • Couleurs Vives Art Friday ArtAbout is a free, vited to write on the wall Studio and Gallery, 222 D monthly, self-guided art- with chalk to contribute a St. Suite 9B, 220-3642; re- walk. Galleries and busi- heartfelt wish, a goal or an ception, 5 – 8 p.m., “Fall in nesses in Davis host a va- COURTESY PHOTOS intention. -

Reality TV Personality Chris Harrison Partners with Seagram's Escapes: New Flavor Seagram's Escapes Tropical Rosé to Hit Sh

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: Cheryl McLean 323-512-3822 [email protected] Reality TV Personality Chris Harrison Partners with Seagram’s Escapes: New Flavor Seagram’s Escapes Tropical Rosé to Hit Shelves this February Rochester, NY – One of reality TV’s most beloved stars is teaming up with one of America’s favorite alcoholic beverage brands, and they’re a perfect match. Reality TV host and social media giant, Chris Harrison, is expanding into the alcoholic beverage space with a brand-new Seagram’s Escapes flavor: Tropical Rosé. The rosé style drink has just 100 calories, similar to seltzers, but is packed with much more taste and made with natural passion fruit and dragon fruit flavors. Tropical Rosé clocks in at 3.2 percent alcohol-by-volume and will be available nationally in four packs of 12-ounce cans starting in February. Harrison has been fully immersed in what is his first alcohol partnership, working closely with the Seagram’s Escapes team to craft the new drink’s flavor, name and packaging. “Creating Tropical Rosé has been a really hands-on experience for me,” said Harrison. “From the very beginning, I traveled with the Seagram’s Escapes team to their flavor house in Chicago to pick just the right color and the perfect fruit flavors. After we were happy with the drink, I had the opportunity to choose the name and weigh in on everything from packaging to advertising. I’m proud of Tropical Rosé and can’t wait for everyone to finally taste it.” “We’re thrilled to have had the opportunity to partner with Chris and to share this drink with both our fans and his,” said Lisa Texido, Seagram’s Escapes brand manager.