'13 Slumping Sox Still Had Nothing on '99

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revere Murder Trial

SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 8, 2018 STEVE KRAUSE | AT LARGE Lynn postal worker Blocksidge was con ned to home more than a eld after assault charge Swampscott By Thor Jourgensen In a report led in court, police said honored a ITEM EDITORIAL DIRECTOR the victim told of cers she was friend- ly with Gillette. The pair communicated war hero LYNN — A postal worker charged with through social media, and she previous- assaulting a Hanover Street woman last ly offered him water and allowed him month must remain con ned to his home to use her bathroom. On Aug. 22, after SWAMPSCOTT — To- and must stay away from the woman for telling the woman he had a package for day, when the Swampscott at least one year. her, Gillette cornered her against a wall High football team opens Gregory Gillette, 30, of Lynn, was free “and began aggressively grabbing her its season at Blocksidge on $5,000 bail when he reported to a and kissing her neck,” according to the Field against Greater hearing at Lynn District Court on Fri- report. Lawrence Regional Tech day. He previously pleaded not guilty The woman told police Gillette put (noon), perhaps it would on Aug. 23 to charges of open and gross his hands down her pants, grabbed her be a great time to ponder lewdness and indecent assault and bat- breasts and exposed his penis. Police the fate of the young man tery on a person 14 or over. advised her to seek a restraining order after whom the complex is Following a review of police reports and tracked Gillette down on his postal named. -

2017 Information & Record Book

2017 INFORMATION & RECORD BOOK OWNERSHIP OF THE CLEVELAND INDIANS Paul J. Dolan John Sherman Owner/Chairman/Chief Executive Of¿ cer Vice Chairman The Dolan family's ownership of the Cleveland Indians enters its 18th season in 2017, while John Sherman was announced as Vice Chairman and minority ownership partner of the Paul Dolan begins his ¿ fth campaign as the primary control person of the franchise after Cleveland Indians on August 19, 2016. being formally approved by Major League Baseball on Jan. 10, 2013. Paul continues to A long-time entrepreneur and philanthropist, Sherman has been responsible for establishing serve as Chairman and Chief Executive Of¿ cer of the Indians, roles that he accepted prior two successful businesses in Kansas City, Missouri and has provided extensive charitable to the 2011 season. He began as Vice President, General Counsel of the Indians upon support throughout surrounding communities. joining the organization in 2000 and later served as the club's President from 2004-10. His ¿ rst startup, LPG Services Group, grew rapidly and merged with Dynegy (NYSE:DYN) Paul was born and raised in nearby Chardon, Ohio where he attended high school at in 1996. Sherman later founded Inergy L.P., which went public in 2001. He led Inergy Gilmour Academy in Gates Mills. He graduated with a B.A. degree from St. Lawrence through a period of tremendous growth, merging it with Crestwood Holdings in 2013, University in 1980 and received his Juris Doctorate from the University of Notre Dame’s and continues to serve on the board of [now] Crestwood Equity Partners (NYSE:CEQP). -

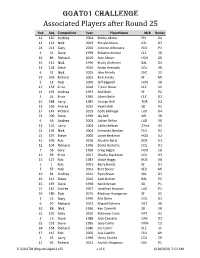

GOAT01 Challenge Associated Players After Round 25

GOAT01 Challenge Associated Players after Round 25 Rnd Seq Competitor Year PlayerName MLB Roster 14 120 Andrea 2004 Bobby Abreu PHI O4 14 124 Nick 2019 Ronald Acuna ATL O2 24 213 Gary 2000 Antonio Alfonseca FLO P3 4 31 Dave 1999 Roberto Alomar CLE 2B 10 86 Richard 2016 Jose Altuve HOU 2B 16 142 Nick 1996 Brady Anderson BAL O4 15 128 Steve 2016 Nolan Arenado COL 3B 6 52 Nick 2015 Jake Arrieta CHC S3 23 203 Richard 2001 Rich Aurilia SF MI 2 18 Rob 2000 Jeff Bagwell HOU 1B 17 153 Ernie 2018 Trevor Bauer CLE S3 22 192 Andrea 1993 Rod Beck SF P2 5 45 Ernie 1995 Albert Belle CLE O2 21 188 Larry 1987 George Bell TOR U2 19 169 Andrea 2010 Heath Bell SD R2 17 149 Richard 2019 Cody Bellinger LAD O4 23 200 Steve 1999 Jay Bell ARI 2B 6 48 Andrea 2004 Adrian Beltre LAD 3B 13 116 Larry 2004 Carlos Beltran 2Tms O5 22 196 Nick 2004 Armando Benitez FLO R2 22 197 Steve 2006 Lance Berkman HOU U2 13 109 Rob 2018 Mookie Betts BOS U1 12 104 Richard 1996 Dante Bichette COL O1 7 58 Gary 1998 Craig Biggio HOU 2B 11 99 Ernie 2017 Charlie Blackmon COL O3 15 127 Rob 1987 Wade Boggs BOS 3B 1 1 Rob 2001 Barry Bonds SF O1 7 57 Nick 2001 Bret Boone SEA MI 10 84 Andrea 2012 Ryan Braun MIL O2 16 143 Steve 2016 Zack Britton BAL P2 16 139 Dave 1998 Kevin Brown SD P1 21 187 Andrea 2007 Jonathan Broxton LAD P1 20 180 Rob 2015 Madison Bumgarner SF S2 2 15 Gary 1996 Ellis Burks COL O2 6 50 Richard 2012 Miguel Cabrera DET 3B 10 88 Nick 1996 Ken Caminiti SD 3B 22 195 Gary 2010 Robinson Cano NYY U2 2 13 Dave 1988 Jose Canseco OAK O2 25 218 Steve 1985 Gary Carter NYM C2 18 158 -

A Long, Strange Trip to Cubs World Series

A long, strange trip to Cubs World Series By George Castle, CBM Historian Posted Friday, October 28, 2016 The Cubs appear a thoroughly dominant team with no holes, and certainly no “Cubbie Occurrences,” in playing the Cleveland Indi- ans in the generations-delayed World Series. But, to steal the millionth time from a song- writer, what a long, strange trip is has been. Truth is stranger than fiction in the Cubs Universe. On my own 45-year path of watch- ing games and talking to the newsmakers at Wrigley Field, I have been a witness to: Burt Hooton slugged a grand-slam homer off Tom “Terrific” Seaver in an 18- 5 pounding of the New York Mets in 1972. Hillary Clinton throws out first ball at Wrigley Field in 1994. On my 19th birthday, May 27, 1974, lefty Ken “Failing” Frailing pitched a complete-game 15-hitter in a 12-4 victory over the San Francisco Giants. A few weeks later, Rich Reuschel tossed a 12-hit shutout against the Lumber Com- pany Pittsburgh Pirates. In mid-Aug. 1974, the Dodgers had 24 hits by the sixth inning in an 18-8 victory over the Cubs. Apparently peeved, the Pirates in late 1975 racked up the most lopsided shutout in history, 22-0 over the Cubs. Reuschel started and gave up eight runs in the first. Brother Paul Reuschel mopped up in the ninth. Rennie Stennett went 7-for-7. Amazingly, less than a month previously, the Reuschels teamed for the only all- brother shutout in history in a 7-0 victory over the Dodgers (also witnessed here). -

Weekly Notes 072817

MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL WEEKLY NOTES FRIDAY, JULY 28, 2017 BLACKMON WORKING TOWARD HISTORIC SEASON On Sunday afternoon against the Pittsburgh Pirates at Coors Field, Colorado Rockies All-Star outfi elder Charlie Blackmon went 3-for-5 with a pair of runs scored and his 24th home run of the season. With the round-tripper, Blackmon recorded his 57th extra-base hit on the season, which include 20 doubles, 13 triples and his aforementioned 24 home runs. Pacing the Majors in triples, Blackmon trails only his teammate, All-Star Nolan Arenado for the most extra-base hits (60) in the Majors. Blackmon is looking to become the fi rst Major League player to log at least 20 doubles, 20 triples and 20 home runs in a single season since Curtis Granderson (38-23-23) and Jimmy Rollins (38-20-30) both accomplished the feat during the 2007 season. Since 1901, there have only been seven 20-20-20 players, including Granderson, Rollins, Hall of Famers George Brett (1979) and Willie Mays (1957), Jeff Heath (1941), Hall of Famer Jim Bottomley (1928) and Frank Schulte, who did so during his MVP-winning 1911 season. Charlie would become the fi rst Rockies player in franchise history to post such a season. If the season were to end today, Blackmon’s extra-base hit line (20-13-24) has only been replicated by 34 diff erent players in MLB history with Rollins’ 2007 season being the most recent. It is the fi rst stat line of its kind in Rockies franchise history. Hall of Famer Lou Gehrig is the only player in history to post such a line in four seasons (1927-28, 30-31). -

San Francisco Giants Weekly Notes: September 21-27, 2020

SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS WEEKLY NOTES: SEPTEMBER 21-27, 2020 Oracle Park 24 Willie Mays Plaza San Francisco, CA 94107 Phone: 415-972-2000 sfgiants.com sfgigantes.com giantspressbox.com @SFGiants @SFGigantes @SFGiantsMedia NEWS & NOTES GIANTS INTERVIEW SCHEDULE The Giants will announce the 2020 Willie Mac Award winner prior to Saturday night's game vs. San Diego. The “Willie McCovey Award” is an annual honor bestowed upon the most inspiration- al player on the San Francisco Giants, as voted upon by the players, coaches, training staff and fans. The award was established in 1980, in honor of former legend and Hall-of-Famer Willie Monday - September 21 McCovey. The winner will receive a plaque engraved with the words “Competitive Spirit, Ability and Leadership” to characterize the qualities both McCovey and the winner exemplifies. 7:35 a.m. - Mike Krukow Strike Out Violence – The Giants will raise awareness for violence prevention during tonight’s joins Murph & Mac game. Longtime Giants community partner La Casa de las Madres remains committed to end- Tuesday - September 22 ing the cycle of violence against women and children in our communities. La Casa continues to provide emergency shelter, a 24/7 hotline and text line and support for women and children 7:35 a.m. - Duane Kuiper facing domestic violence. Since shelter in place, La Casa has sheltered over 100 women and joins Murph & Mac children and provided over 10,000 meals to survivors 4:30 p.m. - Dave Flemming Through the virtual Junior Giants at Home program, Junior Giants reinforced lessons about bul- joins Tolbert, Krueger & Brooks lying prevention. -

Tonight's Game Information

Thursday, August 30, 2018 Game #134 (74-59) Oakland Coliseum SEATTLE MARINERS (74-59) at OAKLAND ATHLETICS (80-54) Road #68 (36-31) TONIGHT’S GAME INFORMATION Starting Pitchers: LHP Wade LeBlanc (7-3, 3.92) vs. RHP Frankie Montas (5-3, 3.75) 7:05 pm PT • Radio: 570 KVI/770 KTTH / Mariners.com • TV: ROOT SPORTS Day Date Opp. Time (PT) Mariners Pitcher Opposing Pitcher RADIO Friday Aug. 31 at OAK 7:05 pm RH Mike Leake (8-8, 4.03) vs. RH Mike Fiers (10-6, 3.15) 710 ESPN Saturday Sept. 1 at OAK 6:05 pm LH James Paxton (10-5, 3.68) vs. RH Daniel Mengden (6-6, 4.28) 710 ESPN Sunday Sept. 2 at OAK 1:05 pm RH Félix Hernández (8-12, 5.49) vs. RH Edwin Jackson (4-3, 3.03) 710 ESPN All games televised on ROOT SPORTS with home games featuring Spanish Audio via TV SAP TONIGHT'S TILT…the Mariners continue their penultimate road trip of the season – a 10-day, 9-game, SCOREBOARD WATCHING 3-city trip – with the 1st of 4 games at the Oakland Athletics…the Mariners opened the road trip taking 2 The Mariners enter play today 8.0 of 3 games vs. the Arizona Diamondbacks at Chase Field and fell 0-2 in a brief 2-game series vs. the San games behind Houston for the lead in the AL West and 5.5 games behind Diego Padres...following this series, will return to Safeco Field on Monday for a 10-day, 8-game homestand Oakland for the final AL Wild Card spot: against Baltimore (3 G), New York-AL (3 G) and San Diego (2 G)…tonight's game will be televised on ROOT TEAM W-L Pct. -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

Triple Plays Analysis

A Second Look At The Triple Plays By Chuck Rosciam This analysis updates my original paper published on SABR.org and Retrosheet.org and my Triple Plays sub-website at SABR. The origin of the extensive triple play database1 from which this analysis stems is the SABR Triple Play Project co-chaired by myself and Frank Hamilton with the assistance of dozens of SABR researchers2. Using the original triple play database and updating/validating each play, I used event files and box scores from Retrosheet3 to build a current database containing all of the recorded plays in which three outs were made (1876-2019). In this updated data set 719 triple plays (TP) were identified. [See complete list/table elsewhere on Retrosheet.org under FEATURES and then under NOTEWORTHY EVENTS]. The 719 triple plays covered one-hundred-forty-four seasons. 1890 was the Year of the Triple Play that saw nineteen of them turned. There were none in 1961 and in 1974. On average the number of TP’s is 4.9 per year. The number of TP’s each year were: Total Triple Plays Each Year (all Leagues) Ye a r T P's Ye a r T P's Ye a r T P's Ye a r T P's Ye a r T P's Ye a r T P's <1876 1900 1 1925 7 1950 5 1975 1 2000 5 1876 3 1901 8 1926 9 1951 4 1976 3 2001 2 1877 3 1902 6 1927 9 1952 3 1977 6 2002 6 1878 2 1903 7 1928 2 1953 5 1978 6 2003 2 1879 2 1904 1 1929 11 1954 5 1979 11 2004 3 1880 4 1905 8 1930 7 1955 7 1980 5 2005 1 1881 3 1906 4 1931 8 1956 2 1981 5 2006 5 1882 10 1907 3 1932 3 1957 4 1982 4 2007 4 1883 2 1908 7 1933 2 1958 4 1983 5 2008 2 1884 10 1909 4 1934 5 1959 2 -

Light Rail Trains Unveiled Socc Initiative No.1 Promotes Rejected by Karie Anderson Music Played and Streamers Involvement Fell As About 200 Invited Guests Ref

Krispy Kreme Sophomore receiv invading local malls er Reggie Williams 192 yards away Page 3 from record Page 6 University of Washington, Tacoma November 13 - November 27, 2002 Vol. 7 No. 4 Voters unite, Light rail trains unveiled socc Initiative No.1 promotes rejected by Karie Anderson Music played and streamers involvement fell as about 200 invited guests Ref. 51 also gets and public citizens witnessed the by Mike Dwyer unveiling of the 66-foot Tacoma voted down link train Nov. 4 at Sound In an effort to build rela tionships among the student by Kayla Cogdill Transit's Tacoma Maintenance Base. organizations on campus and Last Tuesday citizens "The design is absolutely network with non-profit exercised fundamental rights sleek," said Sonja Hall, organizations and businesses and got out to vote. Voters Communications Manager for throughout the community, said no to funding statewide The Tacoma-Pierce County the Community Builders, transportation improvements Chamber and Director of the UWT Life and ASUWT host with their taxes and voted Media Center for Tacoma-Pierce ed the first Student down Tacoina Initiative No. County. "Each train holds up to Organization Collaboration 1, which has been referred to 56 passengers, 30 seated and 26 Consortium, SOCC, Oct. 25. as both an equal rights initia standing." The panel of speakers tive and a slick way to codify The 1.6-mile Tacoma Link consisted of CEO's, directors discrimination against gay, system, expected to be in opera and general managers from lesbian and other sexual tion by September of 2003, will Tacoma's non-profit and pri minorities. -

Police Charge Morrissey Intruder with Felony Theft

New exhibit comes to the Snite Tragedy in Russia Preview the Snite's new art of the An explosion ripped through a Mosco arcade Wednesday Southwest exhibit, "Taos Artists and Their late Tuesday, injuring at least 30 people. Patrons: 1898-1950." page 5 SEPTEMBER 1, page 10-11 1999 O BSERVER The Independent Newspaper Serving Notre Dame and Saint M ary’s VOL XXXIII NO. 7 h t t p ://OBSERVER.ND.EDU S e c u r it y Police charge Morrissey intruder with felony theft Lake, police reported. Seconds “Safety on campus is slept. Hurley recommended dent Richard Klee agreed stu By JOSHUA BOURGEOIS later, an officer responding to students lock doors when not dents are vulnerable to theft. pretty good, but the quick News Wrirvr the call saw a vehicle leave in their rooms. "I think a lot of guys are thief is hard to find. the D-6 parking lot with a Preventative measures starting to lock their doors passenger that matched the A week <>!' thefts in Morrissey Students are very trust “In the past, whenever there more often," Klee said, "[bull I Hall ended Tuesday with a car suspect's description, assis think everybody’s still pretty ing here because they is something stolen, the stu tant director of Notre Dame chase and the arrest of an dents usually left the door laid back about ftheft in the alleged serial burglar. Security/Police Chuck Hurley view it like home. ” open or unlocked,” Hurley dorms]." Lorenzo Jackson, 42, of said. said. “It is very im portant for Considering the vulnerability South Bend, was charged with The officer followed the Father William Seetch students to lock their door.” of rooms in dorms where felony theft and criminal tres vehicle southbound on U.S. -

1987 Topps Baseball Card Checklist

1987 TOPPS BASEBALL CARD CHECKLIST 1 Roger Clemens 2 Jim Deshaies 3 Dwight Evans 4 Dave Lopes 5 Dave Righetti 6 Ruben Sierra 7 Todd Worrell 8 Terry Pendleton 9 Jay Tibbs 10 Cecil Cooper 11 Indians Leaders 12 Jeff Sellers 13 Nick Esasky 14 Dave Stewart 15 Claudell Washington 16 Pat Clements 17 Pete O'Brien 18 Dick Howser 20 Gary Carter 21 Mark Davis 22 Doug DeCinces 23 Lee Smith 24 Tony Walker 25 Bert Blyleven 26 Greg Brock 27 Joe Cowley 28 Rick Dempsey 30 Tim Raines 31 Braves Leaders 31 Braves Leaders (G.Hubbard/R.Ramirez) 32 Tim Leary 33 Andy Van Slyke 34 Jose Rijo 35 Sid Bream 36 Eric King 37 Marvell Wynne 38 Dennis Leonard 39 Marty Barrett 40 Dave Righetti 41 Bo Diaz 42 Gary Redus 43 Gene Michael Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 44 Greg Harris 45 Jim Presley 46 Danny Gladden 47 Dennis Powell 48 Wally Backman 51 Mel Hall 52 Keith Atherton 53 Ruppert Jones 54 Bill Dawley 55 Tim Wallach 56 Brewers Leaders 57 Scott Nielsen 58 Thad Bosley 59 Ken Dayley 60 Tony Pena 61 Bobby Thigpen 62 Bobby Meacham 63 Fred Toliver 64 Harry Spilman 65 Tom Browning 66 Marc Sullivan 67 Bill Swift 68 Tony LaRussa 69 Lonnie Smith 70 Charlie Hough 72 Walt Terrell 73 Dave Anderson 74 Dan Pasqua 75 Ron Darling 76 Rafael Ramirez 77 Bryan Oelkers 78 Tom Foley 79 Juan Nieves 80 Wally Joyner 81 Padres Leaders 82 Rob Murphy 83 Mike Davis 84 Steve Lake 85 Kevin Bass 86 Nate Snell 87 Mark Salas 88 Ed Wojna 89 Ozzie Guillen 90 Dave Stieb 91 Harold Reynolds 92 Urbano Lugo 92A Urbano Lugo Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 2 92B Urbano Lugo 93 Jim