The Color of Welfar.E: How Racism Undermined the War on Poverty I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Max Became a Familiar Face As a Semi- Finalist on the TV Show the Apprentice

James Max became a familiar face as a semi- finalist on the TV show The Apprentice. Now known as the ‘Voice of London’ on LBC radio, he lives in Chelsea and drives a G-Wiz. ME & M Y C A R DC Do you have any regrets about doing the trendy people my age? Because my Dad was programme? obsessed with a particular garage that only JM I loved being associated with something sold Volvos and Fiats. that turned out to be so popular. The tasks have to be televisually friendly, so they have DC Why did you choose the cars you have now? to be quite simple, but each of them draws JM There’s only me and my dog Barney, on some aspect of business, and it doesn’t who’s a Bassett Fauve, and I have an Aston get away from the raw skills you need to be a Martin DB7 Vantage and the G-Wiz. To be success. I still have the satisfaction of having honest, I don’t need the Aston – I hardly been on the winning team eight times out drive it, but it’s a beautiful, responsive, of ten – more than anyone else. You have to invigorating car to drive. I bought it as a adapt to what happens, and whether I was a trophy, for cruising and long distance. Mostly leader or a team player, I was quite good at I drive the G-Wiz or take the bus. People sorting things out. I do regret that although laugh at me either way. -

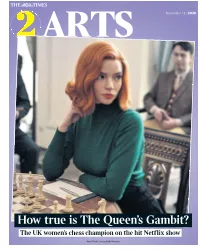

How True Is the Queen's Gambit?

ARTS November 13 | 2020 How true is The Queen’s Gambit? The UK women’s chess champion on the hit Netflix show Anya Taylor-Joy as Beth Harmon 2 1GT Friday November 13 2020 | the times times2 Caitlin 6 4 DOWN UP Moran Demi Lovato Quote of It’s hard being a former Disney child the Weekk star. Eventually you have to grow Celebrity Watch up, despite the whole world loving And in New!! and remembering you as a cute magazine child, and the route to adulthood the Love for many former child stars is Island star paved with peril. All too often the Priscilla way that young female stars show Anyabu they are “all grown up” is by Going revealed her Sexy: a couple of fruity pop videos; preferred breakfast, 10 a photoshoot in PVC or lingerie. which possibly 8 “I have lost the power of qualifies as “the most adorableness, but I have gained the unpleasant breakfast yet invented DOWN UP power of hotness!” is the message. by humankind”. Mary Dougie from Unfortunately, the next stage in “Breakfast is usually a bagel with this trajectory is usually “gaining cheese spread, then an egg with grated Wollstonecraft McFly the power of being in your cheese on top served with ketchup,” This week the long- There are those who say that men mid-thirties and putting on 2st”, she said, madly admitting with that awaited statue of can’t be feminists and that they cannot a power that sadly still goes “usually” that this is something that Mary Wollstonecraft help with the Struggle. -

Michaelmas 2009 Termcard

Mich TheTermcard The Termcard * MICHAELM AS 2009 2009 T H E CAMBRIDGE UNION SOC IET Y • MICHAELMAS TERMCARD WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY JULIEN DOMERCQ THE CAMBRIDGE UNION SOCIETY MICHAELMAS TERM MMIX Printed and bound in Great Britain for The Cambridge Union Society Illustrations by Anna Trench Designed by Dylan Spencer-Davidson Made with a lot of help from Lizzie Robinson and Michael Derringer. Thank you Penguin Books. Contents INTRODUCTION 7 CHAPTER I: DEBATES 10 CHAPTER II: FORUMS 32 CHAPTER III: SPEAKERS 34 Imelda Staunton and Jim Carter 36 Eoin Colfer 37 Ethan Gutmann 38 Terry Eagleton 39 Jo Brand 40 Andrew Rashbass 41 Damian Green MP 42 Dara Ó Briain 43 Former PM John Howard 44 Professor Richard J. Evans 45 Simon Wolfson 46 Jon Sopel 47 Lord Paddy Ashdown 48 Howard Jacobson 49 The Cambridge Union Society John Bolton 50 9A Bridge Street Cambridge CHAPTER IV: SPEAKERS in association with other societies 51 CB2 1UB CHAPTER V: ENTS 58 Office Hours 9.30AM to 5PM T +44 (0) 1223 566 421 Freshers’ Week 60 F +44 (0) 1223 566 444 Weekly Ents 63 www.cus.org / [email protected] Halloween Murder Mystery Party 65 6 CONTENTS Cavatina Chamber Music Concert 66 Love Music Hate Racism Concert 67 WELCOME TO Art Exhibition 68 MICHAELMAS TERM 2009 Cheese Tasting 68 The Union Comedy Club 69 Mexican Fiesta 70 Sushi Making & Tasting 70 Welcome to Michaelmas term at the Union! Whether you are re- Ann Summers Party 71 turning to Cambridge or you have just arrived, we have all worked Christmas Beach Party 71 very hard all summer to make sure that there’s something for everyone here this term. -

Beauty Is Only Skin-Deep, but So Was This Film

10 1G T Wednesday August 14 2019 | the times television & radio Beauty is only skin-deep, but so was this film Burke’s bugbear, understandably, is popularised “heroin chic”. “You have Chris the obscene beauty standard foisted to look at fashion as fantasy — what on women by Love Island, Instagram you are seeing in a magazine is not and the like, jostling more and more real,” were his weasel words. These Bennion young people into therapy or under things look pretty real — in the knife. She began with a visit to the magazines, on television, on social Love Island alumna Megan Barton- media — to teenage girls. Burke said TV review Hanson, a woman not afraid of that heroin chic was “repulsive”. But scalpels. “I don’t want young girls to she said it to the camera, not Rankin. have unrealistic expectations,” said An opportunity missed. Barton-Hanson, a walking unrealistic Beauty is only skin-deep was the expectation. Burke frowned. message Burke kept falling back on, Would a visit to a different idea of but everywhere she turned there were feminine beauty help? Burke has a lot young women desperate to conform to of time for Sue Tilley, the model for a homogenised physical ideal. Burke’s Lucian Freud’s 1995 painting Benefits well-meaning film, alas, was skin-deep Kathy Burke’s All Woman Supervisor Sleeping, a woman entirely too, amounting to an hour of fretting Channel 4 comfortable with her “magnificent and beautifully phrased Burkeisms. {{{(( piles of flesh”. Freud, said Tilley, “Where does this insecurity come Inside the Factory thought that libraries should be from?” Burke asked. -

Broadcast Bulletin Issue Number 98

O fcom Broadcast Bulletin Issue number 98 3 December 2007 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 98 3 December 2007 Contents Introduction 3 Standards cases Notice of Sanction Connection Makers Ltd 4 Babeworld TV, 12 February 2007 In Breach Cops on Camera 5 Bravo, 4 August 2007, 20:00 Looking for the Actual Person 6 Bangla TV, 10 May 2007, 16:00 Jyoti Bangla TV, 16 July 2007, 12:00 Jon Gaunt - Bosch Breakfast Show promotion 8 talkSPORT, 11 October 2007, 10:30 Not in Breach Bringing Up Baby 10 Channel 4, 25 September to 16 October 2007, 21:00 Note to Broadcasters Revised guidance concerning society lotteries 16 Fairness & Privacy cases Not Upheld Complaint by Mr Kaiser Nisar 18 News Bulletin, Sunrise Radio 103.2FM (Yorkshire), 23 March 2006 Other programmes not in breach/outside remit 22 2 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 98 3 December 2007 Introduction Ofcom’s Broadcasting Code (“the Code”) took effect on 25 July 2005 (with the exception of Rule 10.17 which came into effect on 1 July 2005). This Code is used to assess the compliance of all programmes broadcast on or after 25 July 2005. The Broadcasting Code can be found at http://www.ofcom.org.uk/tv/ifi/codes/bcode/ The Rules on the Amount and Distribution of Advertising (RADA) apply to advertising issues within Ofcom’s remit from 25 July 2005. The Rules can be found at http://www.ofcom.org.uk/tv/ifi/codes/advertising/#content From time to time adjudications relating to advertising content may appear in the Bulletin in relation to areas of advertising regulation which remain with Ofcom (including the application of statutory sanctions by Ofcom). -

Broadcast Bulletin Issue Number

Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin Issue number 195 5 December 2011 1 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 195 5 December 2011 Contents Introduction 4 Notice of Sanction Press TV Limited News item, 1 July 2009 5 Standards cases In Breach 50 Super Epic TV Moments E! Entertainment, 7 September 2011, 11:00 7 Keeping Up with the Kardashians E!, 24 September 2011, 12:00 10 Sponsorship of Downton Abbey ITV1, 18 and 25 September, 2, 9, 16 and 23 October 2011, 21:00 12 Resolved Strike Back: Project Dawn Sky 1, 21 August 2011, 4 and 11 September 2011, 21:00 15 Roberto 95.8 Capital FM, 4 October 2011, 11:00 20 News Radio Ikhlas, 16 September 2011, 14:20 23 Broadcast Licensing cases Resolved Breach of Licence Condition Dunoon Community Radio 26 Fairness and Privacy cases Not Upheld Complaint by Ms K Who Needs Fathers, BBC2, 31 March 2010 28 Complaint by Mr Darren Bradley made on his own behalf and on behalf of Bradley and Bradley Limited Cowboy Trap, BBC1, 8 November 2010 63 Complaint by Mr Robert Knight The Hotel Inspector, Channel 5, 23 May 2011 82 2 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 195 5 December 2011 Complaint by Mrs Glynis Braithwaite The Secret Millionaire, Channel 4, 26 April, 2011 90 Other Programmes Not in Breach 94 Complaints Assessed, Not Investigated 95 Investigations List 106 3 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 195 5 December 2011 Introduction Under the Communications Act 2003, Ofcom has a duty to set standards for broadcast content as appear to it best calculated to secure the standards objectives1, Ofcom must include these standards in a code or codes. -

27 Ways to Avoid Gaining Weight Over Christmas

December 8 | 2020 27 ways to avoid gaining Plus Great weight over Christmas gifts for men 2 1GT Tuesday December 8 2020 | the times times2 I always thought that I climbed the Keir Starmer was fit, but not in a sexy lawyer way Shard, went Robert Crampton STEFAN ROUSSEAU/PA to prison, elen Fielding, having naughtily strung everyone along, has Helena’s confirmed that Keir Starmer was not the sofa leaves role model for Mark and now this Darcy in her Bridget me cold Jones books, as played by Colin Firth in the films. Like Fearful of sounding Last Christmas George King was in HFirth in the films, Starmer might be pervy, I try not to sexy in a buttoned-up lawyerly way, write about Helena Fielding says, but she didn’t base her Christensen more than Pentonville, jailed for scaling the UK’s heroine’s love interest on him for the a couple of times a good reason that she has never met year. She’s not easy to tallest building. So why is he still the guy. So that’s that. ignore, however, the Or rather, that will be that once great Dane. At 50 she climbing, asks Candida Crewe I’ve stuck my oar in. Thing is, I know was gadding about in Starmer slightly, having played football a bustier. Now, at 51, with him for a while 25 years ago, she’s ditched even the n Saturday In October last year he was when he was plain mister, not Sir Keir. underwear and been morning, when a lot sentenced to six months in Pentonville I didn’t find him sexy in a buttoned-up photographed naked on of us were doing a for the Shard incident and served lawyerly or any other way, but I can a sofa. -

CD Wins Space in New Wing Mrs Bishop Began Working for MRS EDNA BISHOP ANNOUNCEMENTS Ottawa, Canada, Woke up One- Glaspie Drugs on a Part-Time Olive Grange No

Thousands of ribbons given 304 get 458 immunizations Football practice INSIDE: at 4-H Fairr-Pages BIO, 11, 12, 13 at first free clinic — Page 4B starts Monday — Page 9 A Ith Year No. 18 ST. JOHNS, MICHIGAN THURSDAY AUGUST 25, 1966 2 SECTIONS — 28 PAGES 10 CENTS City reluctant to assess $4.64 for curb, gutter Per foot • • • • • • • • * cost jumps CD wins space Property owners who wince at the thought of paying $4.64 per linear foot for that new curb and gutter this year have a sympathetic companion—the city commission. Commissioners last Tuesday in new wing night expressed some reluctance to assess that much to property owners along about 24 blocks The proposed civil defense emergency of city streets where curb and operating center will be included in the gutter are going in this summer. new east wing of the Clinton County Court * But that's how the costs work out, City Manager Ken Greer house after all. told the commission. And even The board of supervisors, at a special then the city-at-large is picking up about 20 per cent of the meeting last week, voted 16-3 to approve total $80,412 project cost by alternate plan 2 — the EOC. It will cost a paying for the curb and gutter at all the intersections and in total of $34,960, bringing the overall cost front of other public property. of the new wing to $231,476. ABOUT 13,000 OF the 17,300 Late in July the to discuss only that. It lasted linear feet of curb and gutter board had approved only 45 minutes and appeared will be placed in front of private to clear up some hesitancy on property. -

Looking Back on 2006 Ellisons SOLICITORS

Looking Back on 2006 Ellisons SOLICITORS www.ellisonslegal.com Colchester Dovercourt Frinton Headgate Court 45 Kingsway 143 Connaught Avenue Head Street, Colchester Dovercourt, Harwich Frinton on Sea Essex CO1 1NP Essex CO12 3JU Essex CO13 9AB Telephone: +44 (0)1206 764477 Telephone: +44 (0) 1255 502428 Telephone: +44 (0) 1255 851000 Client News Where would any firm be without clients? This section features a selection of Ellisons clients and the work it has carried out for them in the last year. This is by no means comprehensive or indeed fully representative as a great deal of the work Ellisons do is confidential or of such a commercially or personally sensitive nature that it would not be appropriate to put in print. It’s a Family Affair! Client Profile: Mersea Homes Mersea Homes, a third generation family- run business is entering its 60th year. Stuart, Trevor and Darren Cock are running a business founded by Stuart's and Darren's grandfather and the family has high hopes for a fourth generation of the business to come. Stuart recognises the many benefits of keeping things in the family and there is a great sense of pride in holding the business for the next generation. It is not always easy and they all recognise that planning for the transition between one generation and the next is a big challenge, but this is one family business which proves it can be done Stuart can't remember a time that Ellisons was not advising them. This relationship is Concentrating on sites in East Anglia and employee satisfaction is of course further typical of the company's approach. -

Art Books Theatre Film Music Television What's On

Saturday February 20 2021 7-DAY TV & RADIO GUIDE page 23 Ode to Keats Simon Armitage reveals a new poem for the bicentenary It’s a fake! The Dutch forger, Goering’s dodgy Vermeer and a new movie art books theatre film music television what’s on puzzles the times | Saturday February 20 2021 1GR saturday review 3 streaming this week My culture fix 10 Film 11 What the critics are watching and listening to Contents The actor Sanjeev Will Hodgkinson talks Bhaskar lets us into his to the war hero and bank Cover story 4-5 cultural life, from Harry robber Nico Walker, who Rachel Campbell- Potter to Elvis Presley sold the film rights to Johnston on a new his book while serving film about Han van a jail sentence Meegeren, the man who fooled the art world Books 12-21 with his fake Vermeers Princes of the Renaissance, the science Music 6 of debating, facing the SEACIA PAVAO/NETFLIX/THE HOLLYWOOD ARCHIVE The singer Sam Lee truth about Robert E Lee tells Will Hodgkinson and the Confederacy, and about working with the great generals of the English Heritage to First World War breathe new life into folk TV & radio 23-51 Ben Dowell 7 The hit crime drama “The dialogue feels as series Unforgotten if it has been written returns to ITV for a soft porn film”: Devils reviewed Puzzles 52-55 Crosswords, sudoku, Poetry 8-9 Scrabble and your The poet laureate Simon favourite brain teasers Armitage shares an ode to John Keats, 200 years Cover photograph after his hero’s death Alamy Rosamund Pike gives a fearsomely committed performance as a ruthless scammer in the thriller I Care a Lot Film Housewives, and a lot more films, joyous wedding scene — is as close from The Favourite to Broadcast as we can get to the splendour of this I Care a Lot News.