Precarious Policy: the Slow Demise of Combat Service Support

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Grizzly FALL-WINTER 2020

41 CANADIAN BRIGADE GROUP THE GRIZZLY FALL-WINTER 2020 If you have an interesting story, be it in or Everyone has a story out of uniform and want to share it, 41 CBG Tell yours Public Affairs wants to hear from you. For more information on how to get your story published in The Grizzly, contact: Captain Derrick Forsythe Public Affairs Officer 41 Canadian Brigade Group Headquarters Email: [email protected] Telephone: 780-288-7932 or 780-643-6306 Submission deadline for the next edition is 14 May 2021. Photos should be 3 MB or larger for best resolution. Changes of Command + 41 TBG and Brigade Battle school + + DEPLOYING -Individual Augmentation + Boot Review + Exericses - UNIFIED GUNNER I, and CREW FOX ALBERTA’s BRIGADE 41 CANADIAN BRIGADE GROUP ICE CLIMBING • SNOWSHOEING • SKI MOUNTAINEERING EXERCISE GRIZZLY ADVENTURE THEFALL-WINTER 2020 GRIZZLY 13-19 FEBRUARY 21 IN THIS ISSUE .6 Changes of Command .10 BOOT REVIEW - LOWA Z-8S, Rocky S2V, and Salomon Guardian. .12 41 Territorial Battalion Group and 41 Brigade Battle School .16 WARHEADS ON FOREHEADS! LET ‘ER BUCK! - Mortar Course .18 Alberta’s Gunners come together for Ex UNIFIED GUNNER I .22 Podcast Review - Hardcore History .26 Honours and Awards .26 Exercise CREW FOX .26 DEPLOYING - Individual Augmentation .34 PSP: Pre-BMQ/PLQ Workouts THE COVer The cover art was illustrated and coloured by Corporal Reid Fischer from the Calgary Highlanders. The Grizzly is produced by 41 Canadian Brigade Group Public Affairs. Editor - Captain Matthew Sherlock-Hubbard, 41 Canadian Brigade Group Public Affairs Officer Layout - Captain Brad Young, 20 Independent Field Battery, RCA For more information about The Grizzly, contact Captain Derrick Forsythe, Public Affairs Officer, 41 Canadian Brigade Group Headquarters [email protected] or 780-288-7932 1 From the Commander “May you live in interesting times,” is allegedly an ancient Chinese We had 450 members of the Brigade volunteer for Class C With this in mind, we will conduct a centralized Brigade curse. -

Keri L. Kettle

KERI L. KETTLE Assistant Professor, Marketing Cell: 305-494-5207; Work: 305-284-6849 School of Business Administration, U of Miami e-mail: [email protected] Coral Gables, Florida, 33134 URL: www.kerikettle.com/ ACADEMIC POSITIONS Assistant Professor of Marketing Asper School of Business, University of Manitoba, 2016 - present Assistant Professor of Marketing School of Business Administration, University of Miami, 2011 - 2016 EDUCATION PhD, Marketing, School of Business, University of Alberta, 2011 MBA, Marketing, University of Calgary, 2003 BA, Honours, Business Administration, Royal Military College of Canada, 1997 PUBLICATIONS Kettle, Keri L., Remi Trudel, Simon J. Blanchard, and Gerald Häubl, “Putting All Eggs into the Smallest Basket: Repayment Concentration and Consumer Motivation to Get Out of Debt,” forthcoming at Journal of Consumer Research. Kettle, Keri L., and Gerald Häubl (2011), “The Signature Effect: Signing One’s Name Influences Consumption-Related Behavior by Priming Self-Identity,” Journal of Consumer Research, 38 (3), 474-489. Kettle, Keri L., and Gerald Häubl (2010), “Motivation by Anticipation: Expecting Rapid Feedback Enhances Performance,” Psychological Science, 31 (2), 545-547. RESEARCH UNDER REVIEW Kettle, Keri L., Gerald Häubl, and Isabelle Engeler, “Performance-Enhancing Social Contexts: When Sharing Predictions About One’s Performance is Motivating,” invited for resubmission (2nd round) at Journal of Consumer Research. Kettle, Keri L., Katherine E. Loveland, and Gerald Häubl, “The Role of the Self in Self- Regulation: Self-Concept Activation Disinhibits Food Consumption Among Restrained Eaters,” invited for resubmission (2nd round) at Journal of Consumer Psychology. CV – Keri L. Kettle – Page 1 of 8 Kettle, Keri L., and Anthony Salerno, “Anger Promotes Economic Conservatism,” currently under review (1st round) at Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. -

12 (Vancouver) Field Ambulance

Appendix 5 Commanding Officers Rank Name Dates Decorations / WWII 12 Canadian Light Field Ambulance LCol BALDWIN, Sid 1941 to 1942 LCol TIEMAN, Eugene Edward (‘Tuffie’) 1942 to 1943 OBE SBStJ 1 LCol CAVERHILL, Mervyn Ritchie (‘Merv’) 1943 to 1944 OBE LCol McPHERSON, Alexander Donald (‘Don’) 1944 to 1945 DSO Psychiatrist Post-War 12 Field Ambulance LCol CAVERHILL, Mervyn Ritchie (‘Merv’) 1946 to 1946 OBE CO #66 Canadian General Hospital (Which was merged with 24 Medical Company) LCol HUGGARD, Roy 1946 to 1947 24 Medical Company LCol MacLAREN, R. Douglas (‘Doug’) 1947 to 1950 LCol SUTHERLAND, William H. (‘Bill”) 1950 to 1954 LCol ROBINSON, Cecil (‘Cec’) Ernest G. 1954 to 1958 CD QHP Internal Medicine LCol STANSFIELD, Hugh 1958 to 1961 SBStJ CD 2 LCol BOWMER, Ernest John (‘Ernie’) 1961 to 1966 MC CD Director Prov Lab OC Medical Platoon 12 Service Battalion Major NOHEL, Ivan 1976 to 1979 12 (Vancouver) Medical Company Major NOHEL, Ivan 1979 to 1981 CD Major WARRINGTON, Michael (‘Mike’) 1981 to 1983 OStJ CD GP North Van Major GARRY, John 1983 to 1986 CD MHO Richmond LCol DELANEY, Sheila 1986 to 1988 CD Nurse 3 LCol O’CONNOR, Brian 1988 to 1991 CD MHO North Shore LCol FRENCH, Adrian 1991 to 1995 CD LCol WEGENER, Roderick (‘Rod’) Charles 1995 to 2000 CD 12 (Vancouver) Field Ambulance LCol LOWE, David (‘Dave’) Michael 2000 to 2008 CD ESM Peace Officer LCol NEEDHAM, Rodney (‘Rod’) Earl 2008 to 2010 CD Teacher in Surrey LCol ROTH, Ben William Lloyd 2010 to 2014 CD USA MSM LCol FARRELL, Paul 2014 to 2016 CD ex RAMC LCol McCLELLAND, Heather 2016 to present CD Nursing Officer 1 Colonel Tieman remained in the RCAMC after the war and was the Command Surgeon Eastern Army Command in 1954; he was made a Serving Brother of the Order of St. -

The Perception Versus the Iraq War Military Involvement in Sean M. Maloney, Ph.D

Are We Really Just: Peacekeepers? The Perception Versus the Reality of Canadian Military Involvement in the Iraq War Sean M. Maloney, Ph.D. IRPP Working Paper Series no. 2003-02 1470 Peel Suite 200 Montréal Québec H3A 1T1 514.985.2461 514.985.2559 fax www.irpp.org 1 Are We Really Just Peacekeepers? The Perception Versus the Reality of Canadian Military Involvement in the Iraq War Sean M. Maloney, Ph.D. Part of the IRPP research program on National Security and Military Interoperability Dr. Sean M. Maloney is the Strategic Studies Advisor to the Canadian Defence Academy and teaches in the War Studies Program at the Royal Military College. He served in Germany as the historian for the Canadian Army’s NATO forces and is the author of several books, including War Without Battles: Canada’s NATO Brigade in Germany 1951-1993; the controversial Canada and UN Peacekeeping: Cold War by Other Means 1945-1970; and the forthcoming Operation KINETIC: The Canadians in Kosovo 1999-2000. Dr. Maloney has conducted extensive field research on Canadian and coalition military operations throughout the Balkans, the Middle East and Southwest Asia. Abstract The Chrétien government decided that Canada would not participate in Operation Iraqi Freedom, despite the fac ts that Canada had substantial national security interests in the removal of the Saddam Hussein regime and Canadian military resources had been deployed throughout the 1990s to contain it. Several arguments have been raised to justify that decision. First, Canada is a peacekeeping nation and doesn’t fight wars. Second, Canada was about to commit military forces to what the government called a “UN peacekeeping mission” in Kabul, Afghanistan, implying there were not enough military forces to do both, so a choice had to be made between “warfighting” and “peacekeeping.” Third, the Canadian Forces is not equipped to fight a war. -

TRAINING to FIGHT and WIN: TRAINING in the CANADIAN ARMY (Edition 2, May 2001)

ttrainingraining ttoo fightfight andand wwin:in: ttrainingraining inin thethe canadiancanadian aarrmymy Brigadier-General Ernest B. Beno, OMM, CD (Retired) Foreword by Brigadier-General S.V. Radley-Walters, CMM, DSO, MC, CD Copyright © Ernest B. Beno, OMM, CD Brigadier-General (Retired) Kingston, Ontario March 22, 1999 (Retired) TRAINING TO FIGHT AND WIN: TRAINING IN THE CANADIAN ARMY (Edition 2, May 2001) Brigadier-General Ernest B. Beno, OMM, CD (Retired) Foreword By Brigadier-General S.V. Radley-Walters, CMM, DSO, MC, CD (Retired) TRAINING TO FIGHT AND WIN: TRAINING IN THE CANADIAN ARMY COMMENTS AND COMMENTARY “I don’t have much to add other than to support the notion that the good officer is almost always a good teacher.” • Lieutenant-Colonel, (Retired), Dr. Doug Bland, CD Queen’s University “ Your booklet was a superb read, packed with vital lessons for our future army - Regular and Reserve!” • Brigadier-General (Retired) Peter Cameron, OMM, CD Honorary Colonel, The 48th Highlanders of Canada Co-Chair Reserves 2000 “This should be mandatory reading for anyone, anywhere before they plan and conduct training.” • Lieutenant-Colonel Dave Chupick, CD Australia “I believe that your booklet is essential to the proper conduct of training in the Army, and I applaud your initiative in producing it. As an overall comment the individual training of a soldier should ensure the ability to ‘march, dig and shoot.’ If these basics are mastered then the specialty training and collective training can be the complete focus of the commander’s/CO’s concentration.” • Colonel (Retired) Dick Cowling London, ON “I think this is the first ‘modern’ look at training in the Canadian Army that I heard of for thirty years. -

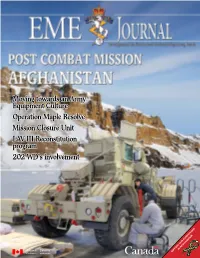

Operation Maple Resolve LAV III Reconstitution Program 202 WD's Involvement Moving Towards an Army Equipment Culture Mission C

Moving towards an Army Equipment Culture Operation Maple Resolve Mission Closure Unit LAV III Reconstitution program 202 WD’s involvement in Afghanistan support our companions EME Journal Regimental Command OST OMBAT ISSION FGHANISTAN 4 Branch Advisor’s Message EME P C M - A The need for an equipment culture and technological Moving towards an Army advice. 6 Equipment Culture Branch Chief Warrant Officer’s Exercise Maple Resolve 5 Message 8 Afghanistan is winding down and our skill-sets have Following years of combat and training specific to a become very specific, Ex Maple Resolve was the theatre of war, the EME Branch must now refocus perfect opportunity to address this issue. itself. 9 Mission Closure Unit 20 Learning and Action The LAV III Reconstitution 12 Operation Nanook 2011 10 program Op Nanook 2011 is one of the three major recurring With the end of the Kandahar mission the LAV III sovereignty Operations conducted annually by the CF LORIT fleet was pulled from theatre and shipped to in the North. London, Ontario for a re-set. 11 202 WD’s involvement What’s up? Trade Section 19 MOBILE trial on Ex Maple Resolve 26 Electronics and Optronics Tech The MOBILE solution permits Materiel Acquisition and 2012 EO Tech Focus Group Support (MA&S) activity in areas where connectivity to the DWAN is not available or is disrupted. 26 Materials Tech 14 Leopard 2A4M Course North American Technology Beyond the modular tent; a look at the trial of the On Oct 1st, 2011, twenty-four Mil and Civ students, 20 Demonstration 1000 Pers RTC Kitchen Project. -

Caf Logistics Force Protection

CAF LOGISTICS FORCE PROTECTION Major A.M. McCabe JCSP 40 PCEMI 40 Exercise Solo Flight Exercice Solo Flight Disclaimer Avertissement Opinions expressed remain those of the author and do Les opinons exprimées n’engagent que leurs auteurs et not represent Department of National Defence or ne reflètent aucunement des politiques du Ministère de Canadian Forces policy. This paper may not be used la Défense nationale ou des Forces canadiennes. Ce without written permission. papier ne peut être reproduit sans autorisation écrite. © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the © Sa Majesté la Reine du Chef du Canada, représentée par le Minister of National Defence, 2014. ministre de la Défense nationale, 2014. 1 CANADIAN FORCES COLLEGE – COLLÈGE DES FORCES CANADIENNES JCSP 40 – PCEMI 40 SOLO FLIGHT CAF LOGISTICS FORCE PROTECTION: By Major A.M. McCabe Par le major A.M. McCabe “This paper was written by a student “La présente étude a été rédigée par attending the Canadian Forces College un stagiaire du Collège des Forces in fulfilment of one of the requirements canadiennes pour satisfaire à l'une des of the Course of Studies. The paper is exigences du cours. L'étude est un a scholastic document, and thus document qui se rapporte au cours et contains facts and opinions, which the contient donc des faits et des opinions author alone considered appropriate que seul l'auteur considère appropriés and correct for the subject. It does not et convenables au sujet. Elle ne reflète necessarily reflect the policy or the pas nécessairement la politique ou opinion of any agency, including the l'opinion d'un organisme quelconque, y Government of Canada and the compris le gouvernement du Canada et Canadian Department of National le ministère de la Défense nationale du Defence. -

33 Service Battalion

33 Service Battalion Fort Chippewa Barracks 540 Chippewa St. W. North Bay, ON Trades Description Mobile Support Equipment Operator 33 Service Battalion is a Combat Service and (MSE Op) operates military vehicles ranging in Support unit in the Canadian Army Reserve, as size from standard automobiles to snow removal part of the 33 Canadian Brigade Group and has equipment and all-terrain vehicles in support of 3 locations in Ottawa, North Bay and Sault Ste. the mobility of the Canadian Armed Forces. Marie. Members of the Army Reserve are Qualifications received are transferable to your citizens who are paid to take military training on civilian license. a part-time basis to assist the Regular Force in meeting Canada's military commitments. Weapons Technician works as a member of a maintenance organization located in base or In addition to their part-time work members of field locations and is employed in the repair and the Army Reserve can take full-time courses maintenance of all army weapons. during the summer months, or can apply for full- time positions once they have received sufficient Vehicle Technician belongs to the Electrical training. Members can also apply for certain and Mechanical Engineering Branch of the postings with Regular Force Units. Canadian Forces. Each Vehicle Technician is a member of a team responsible for maintaining, The Canadian Army Reserve has many repairing and overhauling CAF land vehicles and opportunities in a variety of trades. Training is related equipment to keep them in top condition. offered on a part-time basis with training on evenings and weekends to work with people Cook in the Reserve prepares a variety of who are students and full time employees. -

Lcol Jansen Will Retire on 13 February 2019

RETIREMENT MESSAGE LCol C.R. Jansen, CD, BMASc, CET, P.LOG. KStG, PMSC After 40 years of loyal service in the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF), LCol Jansen will retire on 13 February 2019. LCol Jansen started his military career as a CIL Air Officer in Oct 1978, rose through the ranks to command the Flight School in CFB North Bay in 1983. In 1984, he joined the Corps by transferring into the Primary Reserve with 26 Service Battalion Maint Coy as their training officer then to 2 Svc Bn Maint Coy in 1986 to Deploy to Norway on OPERATION BRAVE LION and then DGLEPM/BADP/BSAMS in Ottawa until 1988 where he transferred to 25 (Toronto) Service Battalion. He served as Unit Adjutant, Operations Officer, Recruiting Officer, OC Maint Coy, OC Admin Coy, Snr Log Ops O, DCO, and Commanding Officer from 2012 to 2014. During his employment at DGLEPM as part of the BSAMS team, he developed the Corps first computerized version of the 1020D including base MOC, time reporting, and a LOMMIS data update capability. In 1990, he served in Toronto Militia District HQ as G4 Maint-2. In 1996, while OC Maint he implemented the first successful college coop program to develop QL5 certified Veh Techs. LCol Jansen remained Class A for 15 years employed as a Computer Consultant, following 9/11, he was asked to switch to full time helping with the stand up of 2 ASG as the G3 Maint in 2001 and helped to create the GS Battalion. He was employed as the LFCA HQ SO BP and later as the G5. -

Diefenbunker Alumni

DIEFENBUNKER ALUMNI May 2014 Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Patron .............................................................................................................................................. 4 Riegel, Henriette (Yetta) ............................................................................................................. 4 Regular Members ............................................................................................................................ 5 Barr, Art ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Bernier, Michel............................................................................................................................ 6 Brooks, Norman E. ...................................................................................................................... 6 Bulach, Jeff.................................................................................................................................. 7 Campbell, George........................................................................................................................ 7 Capel, Peter ................................................................................................................................. 8 Chaplin, David ........................................................................................................................... -

Wo Jonathan Harper Cd1, 00129 Veh Tech

RETIREMENT –WO JONATHAN HARPER CD1, 00129 VEH TECH After completing more than 29 years in the CAF both as a Regular force Vehicle Tech and a Reserve Weapons Tech, WO Jonathan Harper retired on the 16 August 2018. WO Jon Harper enlisted in the Army Reserves as a Weapons Technician as part of 21 Service Battalion in Windsor, Ontario on 15 Nov 1989. He spent the next five years as a reservist and completed up to the QL6A trade level for Reserve Weapons Technicians. It was at this point that he decided a full time career in the CAF was what he wanted to do. He tried to do a Component Transfer within the same trade, but due to personnel cut-backs in the forces in the mid-nineties, there were no positions available. The recruiter called him after a few months of waiting to offer him a position as a Vehicle Technician. Seeing as this was still a part of the EME Branch, he agreed. The transfer ceremony happened on 26 January 1995, when he was 24 years old. Eight days later, he began his new trade training at the Canadian Forces School of the Electrical and Mechanical Engineering (now known as the RCEME School) in CFB Borden. After completing his QL 3 Veh Tech course in August of 1995, he was posted to CFB Calgary as a member of 1 Service Battalion (1 Svc Bn) and was employed in a variety of positions in Maintenance Company while continuing to learn his trade. As the base in Calgary was being downsized, he was posted to CFB Edmonton in the summer of 1996. -

1 MERITORIOUS SERVICE MEDAL (Military)

MERITORIOUS SERVICE MEDAL (Military) (MSM) CITATIONS 04 August 2012 to 08 December 2012 UPDATED: 11 November 2020 PAGES: 40 CORRECT TO: 08 December 2012 CG Prepared by: John Blatherwick ================================================================================================= Citations in this Folder PAGE NAME RANK UNIT DECORATIONS / 03 ADAMS, Derek John Major Mentoring to Cdr Maywand District Police HQ MSM CD 18 AUGER, Joseph Claude Patrick Sergeant Evacuation of a Heavily Booby-Trapped Buildings MSM CD 19 BELCOURT, Joseph Mario Claude CWO Canadian Forces Support Unit CWO MMM MSM CD 19 BLAIS, Gérard Joseph Colonel Director of Casualty Support Management OMM MSM CD 03 BRUCE, Malcolm David LCol Work at the National Military Hospital Afghanistan MSM CD 04 CAMPBELL, Yannick Sergeant Engineer Construction Team in Afghanistan MSM CD 20 CESSFORD, Michael Pearson Colonel Cdr-Language Training Centre Afghanistan OMM MSM CD 04 CHAMPAGNE, Joseph Guy Alain Richmond MWO Road-building project Panjwayi District Afghanistan MSM CD 04 COLE, Michael James Major OC Maintenance Company in Afghanistan MSM CD 05 CREIGHTON, Ian Robert Colonel CO Operational Mentor & Liaison Team Afghan MSM CD 05 CULLEN Gordon Percy Sergeant Battalion Group Master Sniper in Afghanistan MSM CD 20 DALLAIRE, Joseph Yvon Prudent Claude MWO Cdn Helicopter Maintenance Sqd Afghanistan OMM MSM CD 05 DOUGLAS, Austin Matthew Major OC Bravo Company RCR Afghanistan MSM CD 21 DUFAULT, Raymond Jean François Major DCO - R22eR Battle Group JTF Afghanistan MSM CD 06 DUFFY, Scott William Major Senior Mentor Police OMLET Afghanistan MSM CD 23 ERRINGTON, John William LCol Cdr - Special Operations Task Group Afghanistan MSM CD 06 FILIATRAULT, Marc Charles Joseph WO Assisted a young man involved in a car accident MSM CD 07 FRANCIS, Joy Corporal All Source Intelligence Centre MSM 24 FREEMAN, Myra Ava HCaptain(N) RCN / Lt-Gov.