Reading Stein and Barnes As Hybrid Architects Marc Patrick Malone Iowa State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Humble Protest a Literary Generation's Quest for The

A HUMBLE PROTEST A LITERARY GENERATION’S QUEST FOR THE HEROIC SELF, 1917 – 1930 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jason A. Powell, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Steven Conn, Adviser Professor Paula Baker Professor David Steigerwald _____________________ Adviser Professor George Cotkin History Graduate Program Copyright by Jason Powell 2008 ABSTRACT Through the life and works of novelist John Dos Passos this project reexamines the inter-war cultural phenomenon that we call the Lost Generation. The Great War had destroyed traditional models of heroism for twenties intellectuals such as Ernest Hemingway, Edmund Wilson, Malcolm Cowley, E. E. Cummings, Hart Crane, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and John Dos Passos, compelling them to create a new understanding of what I call the “heroic self.” Through a modernist, experience based, epistemology these writers deemed that the relationship between the heroic individual and the world consisted of a dialectical tension between irony and romance. The ironic interpretation, the view that the world is an antagonistic force out to suppress individual vitality, drove these intellectuals to adopt the Freudian conception of heroism as a revolt against social oppression. The Lost Generation rebelled against these pernicious forces which they believed existed in the forms of militarism, patriotism, progressivism, and absolutism. The -

Narrating Queer Abjection in Djuna Barnes's Nightwood and Jordy Rosenberg's Confessions Of

“BEASTS WHO WALK ALONE”: NARRATING QUEER ABJECTION IN DJUNA BARNES’S NIGHTWOOD AND JORDY ROSENBERG’S CONFESSIONS OF THE FOX BY JAKE J. MCGUIRK A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of WAKE FOREST UNIVSERITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS English May 2021 Winston-Salem, North Carolina Approved By: Omaar Hena, PhD, Advisor Jefferson Holdridge, PhD, Chair Meredith Farmer, PhD ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I owe a special thanks to Omaar Hena for encouraging this project from the very beginning, and much gratitude to my readers Meredith Farmer and Jeff Holdridge for their invaluable advice and emotional support. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS I) Abstract.............................................................................................................iv II) Introduction........................................................................................................v III) Queer Animality in Barnes’s Nightwood...........................................................1 IV) Queer, Post/Colonial Hybridity in Rosenberg’s Confessions of the Fox.........15 V) Human, Inhuman, Queer..................................................................................24 VI) References........................................................................................................27 VII) Curriculum Vitae.............................................................................................31 iii ABSTRACT This essay explores paradoxes surrounding queer abjection by -

Gertrude Stein and Her Audience: Small Presses, Little Magazines, and the Reconfiguration of Modern Authorship

GERTRUDE STEIN AND HER AUDIENCE: SMALL PRESSES, LITTLE MAGAZINES, AND THE RECONFIGURATION OF MODERN AUTHORSHIP KALI MCKAY BACHELOR OF ARTS, UNIVERSITY OF LETHBRIDGE, 2006 A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of the University of Lethbridge in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of English University of Lethbridge LETHBRIDGE, ALBERTA, CANADA © Kali McKay, 2010 Abstract: This thesis examines the publishing career of Gertrude Stein, an American expatriate writer whose experimental style left her largely unpublished throughout much of her career. Stein’s various attempts at dissemination illustrate the importance she placed on being paid for her work and highlight the paradoxical relationship between Stein and her audience. This study shows that there was an intimate relationship between literary modernism and mainstream culture as demonstrated by Stein’s need for the public recognition and financial gains by which success had long been measured. Stein’s attempt to embrace the definition of the author as a professional who earned a living through writing is indicative of the developments in art throughout the first decades of the twentieth century, and it problematizes modern authorship by re- emphasizing the importance of commercial success to artists previously believed to have been indifferent to the reaction of their audience. iii Table of Contents Title Page ………………………………………………………………………………. i Signature Page ………………………………………………………………………… ii Abstract ……………………………………………………………………………….. iii Table of Contents …………………………………………………………………….. iv Chapter One …………………………………………………………………………..... 1 Chapter Two ………………………………………………………………………….. 26 Chapter Three ………………………………………………………………………… 47 Chapter Four .………………………………………………………………………... 66 Works Cited .………………………………………………………………………….. 86 iv Chapter One Hostile readers of Gertrude Stein’s work have frequently accused her of egotism, claiming that she was a talentless narcissist who imposed her maunderings on the public with an undeserved sense of self-satisfaction. -

The Radical Ekphrasis of Gertrude Stein's Tender Buttons Georgia Googer University of Vermont

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM Graduate College Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 2018 The Radical Ekphrasis Of Gertrude Stein's Tender Buttons Georgia Googer University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis Recommended Citation Googer, Georgia, "The Radical Ekphrasis Of Gertrude Stein's Tender Buttons" (2018). Graduate College Dissertations and Theses. 889. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/889 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate College Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RADICAL EKPHRASIS OF GERTRUDE STEIN’S TENDER BUTTONS A Thesis Presented by Georgia Googer to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Specializing in English May, 2018 Defense Date: March 21, 2018 Thesis Examination Committee: Mary Louise Kete, Ph.D., Advisor Melanie S. Gustafson, Ph.D., Chairperson Eric R. Lindstrom, Ph.D. Cynthia J. Forehand, Ph.D., Dean of the Graduate College ABSTRACT This thesis offers a reading of Gertrude Stein’s 1914 prose poetry collection, Tender Buttons, as a radical experiment in ekphrasis. A project that began with an examination of the avant-garde imagism movement in the early twentieth century, this thesis notes how Stein’s work differs from her Imagist contemporaries through an exploration of material spaces and objects as immersive sensory experiences. This thesis draws on late twentieth century attempts to understand and define ekphrastic poetry before turning to Tender Buttons. -

Gertrude Stein's "Melanctha" and the Problem of Female Empowerment

Moving Away from Nineteenth Century Paradigms: Gertrude Stein's "Melanctha" and the Problem of Female Empowerment Adrianne Kalfopoulou Aristotle Udiversity Thessaloniki The increasing visibility of a self in process motivated by either conscious or unconscious desire-some assertion of the self in conflict with the structural boundaries of gendered, racist conduct-marks one expression of a general movement at the turn-of-the-century away from the given canons of nineteenth century historicity. With Three Lives, a pioneering, modernist work published in 1909, Gertrude Stein takes direct issue with nineteenth century paradigms of proper gender conduct, emphasizing their cultural/linguistic construct as opposed to what, historically, were considered their natural/biological character.1 In "Melanctha," the second and longest of the three narratives that make up Three Lives, we are introduced to the mulatto heroine Melanc- tha whose restless complexity does not allow her to settle into any of the conventional female roles. From the first, the traditional constructs of wife and motherhood with their implicit propriety are questioned. Rose Johnson, Melanctha's black friend, is the one who is married, the one who has given birth. But while Melanctha is "patient, submissive, soothing, and untiring" (81) in her regard for Rose and her baby, Rose herself is "careless, negligent, and selfish" toward Melanctha and, more importantly, toward her own child.2 We are told that Rose's negligence 1 (New York: Signet Classic [1909) 1985). 2 Ekaterini Georgoudaki goes into in-depth discussion of black, female stereotypes and how contemporary black women writers work lo revise these inheriled, pre-exisling, cultural and literary stereotypes. -

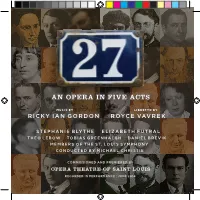

An Opera in Five Acts

AN OPERA IN FIVE ACTS MUSIC BY LIBRETTO BY RICKY IAN GORDON ROYCE VAVREK STEPHANIE BLYTHE ELIZABETH FUTRAL THEO LEBOW TOBIAS GREENHALGH DANIEL BREVIK MEMBERS OF THE ST. LOUIS SYMPHONY CONDUCTED BY MICHAEL CHRISTIE COMMISSIONED AND PREMIERED BY OPERA THEATRE OF SAINT LOUIS RECORDED IN PERFORMANCE : JUNE 2014 1 CD 1 1) PROLOGUE | ALICE KNITS THE WORLD [5:35] ACT ONE 2) SCENE 1 — 27 RUE DE FLEURUS [10:12] ALICE B. TOKLAS 3) SCENE 2 — GERTRUDE SITS FOR PABLO [5:25] AND GERTRUDE 4) SCENE 3 — BACK AT THE SALON [15:58] STEIN, 1922. ACT TWO | ZEPPELINS PHOTO BY MAN RAY. 5) SCENE 1 — CHATTER [5:21] 6) SCENE 2 — DOUGHBOY [4:13] SAN FRANCISCO ACT THREE | GÉNÉRATION PERDUE MUSEUM OF 7) INTRODUCTION; “LOST BOYS” [5:26] MODERN ART. 8) “COME MEET MAN RAY” [5:48] 9) “HOW WOULD YOU CHOOSE?” [4:59] 10) “HE’S GONE, LOVEY” [2:30] CD 2 ACT FOUR | GERTRUDE STEIN IS SAFE, SAFE 1) INTRODUCTION; “TWICE DENYING A WAR” [7:36] 2) “JURY OF MY CANVAS” [6:07] ACT FIVE | ALICE ALONE 3) INTRODUCTION; “THERE ONCE LIVED TWO WOMEN” [8:40] 4) “I’VE BEEN CALLED MANY THINGS" [8:21] 2 If a magpie in the sky on the sky can not cry if the pigeon on the grass alas can alas and to pass the pigeon on the grass alas and the magpie in the sky on the sky and to try and to try alas on the grass the pigeon on the grass and alas. They might be very well very well very ALICE B. -

Djuna Barnes's Bewildering Corpus. by Daniela Caselli. Burlington, VT

Book Reviews Improper Modernism: Djuna Barnes’s Bewildering Corpus. By Daniela Caselli. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2009. x + 290 pp. $114.95 cloth. Modernist Articulations: A Cultural Study of Djuna Barnes, Mina Loy, and Gertrude Stein. By Alex Goody. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007. xii + 242 pp. $75.00 cloth. TextWkg.indd 153 1/4/11 3:35:48 PM 154 THE SPACE BETWEEN Djuna Barnes’ Consuming Fictions. By Diane Warren. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2008. xviii + 188 pp. $99.95 cloth. It is something of a scandal that so many people read Nightwood, a text that used to be so scandalous. For much of the twentieth century, the obscurity of Djuna Barnes’s novel was considered to be a central part of its appeal. To read or recommend it was to participate in a subversive or subcultural tradition, an alternative modernism that signified variouslylesbian , queer, avant-garde. Within the expanded field of recent modernist scholarship, however, Barnes’s unread masterpiece is now simply a masterpiece, one of the usual suspects on conference programs and syllabi. Those of us who remain invested in Barnes’s obscurity, however, can take comfort in the fact that, over the course of her long life and comparatively short career, Barnes produced an unruly body of work that is unlikely to be canonized. Indeed, Barnes’s reputation has changed: once treated as one of modern- ism’s interesting background figures, fodder to fill out the footnotes of her more famous male colleagues, she has now become instead a single-work author, a one-hit wonder. And no wonder; the rest of her oeuvre is made up of journalism, a Rabelaisian grab-bag of a novel, seemingly slight poems and stories, a Jacobean revenge drama, and an alphabetic bestiary. -

A Critical Study of the Loss and Gain of the Lost Generation

Opción, Año 34, Especial No.15 (2018): 1436-1463 ISSN 1012-1587/ISSNe: 2477-9385 A Critical Study of the Loss and Gain of the Lost Generation Seyedeh Zahra Nozen1 1Department of English, Amin Police Science University [email protected] Shahriar Choubdar (MA) Malayer University, Malayer, Iran [email protected] Abstract This study aims to the evaluation of the features of the group of writers who chose Paris as their new home to produce their works and the overall dominant atmosphere in that specific time in the generation that has already experienced war through comparative research methods. As a result, writers of this group tried to find new approaches to report different contexts of modern life. As a conclusion, regardless of every member of the lost generation bohemian and wild lifestyles, the range, creativity, and influence of works produced by this community of American expatriates in Paris are remarkable. Key words: Lost Generation, World War, Disillusionment. Recibido: 04-12--2017 Aceptado: 10-03-2018 1437 Zahra Nozen and Shahriar Choubdar Opción, Año 34, Especial No.15(2018):1436-1463 Un estudio crítico de la pérdida y ganancia de la generación perdida Resumen Este estudio tiene como objetivo la evaluación de las características del grupo de escritores que eligieron París como su nuevo hogar para producir sus obras y la atmósfera dominante en ese momento específico en la generación que ya ha experimentado la guerra a través de métodos de investigación comparativos. Como resultado, los escritores de este grupo trataron de encontrar nuevos enfoques para informar diferentes contextos de la vida moderna. -

Djuna Barnes Nightwood. a Modernist Exercise

ENRIQUE GARCÍA DIEZ UNIVERSIDAD DE VALENCIA DJUNA BARNES'NIGHTWOOD; A MODERNIST EXERCISE "On or about December 1910 human life changed." These now famous words of Virginia Woolf tried to reflect the consciousness of the speed of change at the beginning of the century. This sort of dramatic or prophetic gesture only revealed the intensity with which writers and artists of all kinds lived one of the most dynamic periods of hvunan history. James McFarlane and Malcom Bradbury go so far as to say that Modernism was one of those overwhelming dislocations in human perception which changed man's sensibility and man's relationship to history permanently. In its multiplicity and brilliant confusión, its commitment to an aesthetic of endless renewal, or as Irving Howe calis it, its improvisation of "the tradition of the new," Modernism is still open to analysis and to debate. Even if we are talking of Postmodernism and even Post-postmodernism, the period we are referring to now (first quarter of the century, roughly) does not have a single concrete and aesthetic reference. As a matter of fact, few ages been as múltiple and as promiscuous in their artistic cholees as was Modernism. Very often, though, the tendency to sophistication and mannerism, to introversión, and to technical display for its own sake and even internal scepticism have often been cited as essential in the definition of Modernism. And since the terms have a vague connotation, we will have to establish some kind of framework of reference or definition of the movement in order to move relatively safely in the analysis of a novel often mentioned as a masterpiece of modern aesthetics. -

Centered Fluidity and the Horizons of Continuity in Djuna Barnes' Nightwood Maria C

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 11-6-2012 Centered Fluidity and the Horizons of Continuity in Djuna Barnes' Nightwood Maria C. Sepulveda Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI12112802 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Sepulveda, Maria C., "Centered Fluidity and the Horizons of Continuity in Djuna Barnes' Nightwood" (2012). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 746. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/746 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida CENTERED FLUIDITY AND THE HORIZONS OF CONTINUITY IN DJUNA BARNES’ NIGHTWOOD A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in ENGLISH by Maria Sepulveda 2012 To: Dean Kenneth G. Furton College of Arts and Sciences This thesis, written by Maria Sepulveda, and entitled Centered Fluidity and the Horizons of Continuity in Djuna Barnes' Nightwood, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this thesis and recommend that it be approved. _______________________________________ Phillip Marcus _______________________________________ Maneck Daruwala _______________________________________ Ana Luszczynska, Major Professor Date of Defense: November 6, 2012 The thesis of Maria Sepulveda is approved. _______________________________________ Dean Kenneth G. Furton College of Arts and Sciences _______________________________________ Dean Lakshmi N. -

World War I, Modernism, and Perceptions of Sexual Identity

ABSTRACT ENTRENCHED PERSONALITIES: WORLD WAR I, MODERNISM, AND PERCEPTIONS OF SEXUAL IDENTITY by Tyler R. Groff This thesis considers how modernists used WWI as a platform to critique sexual norms and explore sexual diversity. Though the war was characterized by heteronormative rhetoric and policies that encouraged strict gender division, many writers of the era suggest that such measures only counterintuitively highlighted dissident sexual positionalities and encouraged a broad range of war workers and citizens, intellectuals and non-intellectuals alike, to contemplate complex notions of sexual identity. Gertrude Stein’s The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, Djuna Barnes’ Nightwood, and David Jones’ In Parenthesis are considered in respective chapters. Though these works largely contrast in terms of genre, theme, and authorship, each questions war propaganda and sexological discourse that attempted to essentialize gender and/or pathologize homosexuality. In addition, each work implies that WWI brought questions of sexual identity to the minds of soldiers and war workers, even those far removed from the discursive spaces of sexology and psychology. ENTRENCHED PERSONALITIES: WORLD WAR I, MODERNISM, AND PERCEPTIONS OF SEXUAL IDENTITY A thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English by Tyler R. Groff Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2013 Advisor: Dr. Madelyn Detloff Reader: Dr. Erin Edwards Reader: Dr. Mary Jean Corbett Table of Contents Introduction -

Lowry's Reading

LOWRY'S READING An Introductory Essay W. H. New 1Ν TWO LARGE BOXES at the University of British Columbia are the remnants of Malcolm Lowry's library, a motley collection of works that ranges from Emily Brontë and Olive Schreiner to Djuna Barnes and Virginia Woolf, from the Kenyon, Partisan, and Sewanee Reviews to A Pocketful of Canada, from Latin Prose Composition to the Metropolitan Opera Guide, and from Elizabethan plays to Kafka and Keats. Little escaped his attention, in other words, and even such a partial list as this one indicates his eclectic and energetic insatiability for books. That he was also an inveterate film-goer and jazz en- thusiast, and that he absorbed and remembered everything he experienced, makes any effort to separate out the individual influences on his work an invidious one; rather like chasing a rabbit through Ali Baba's caves, the activity seems in- commensurate with its surroundings. But on frequent occasions an appreciation of the scope of his references or the source of a single allusion will take us closer to Lowry's tone and method. Richard Hauer Costa, for example, writing in the University of Toronto Quarterly in 1967, points out that "unacknowledged literary kinship" between Under the Volcano, Aiken's Blue Voyage, and Joyce's Ulysses: the central use of the quest theme, the burgeoning sense of remorse, the "impatience" of the author with usual narrative methods, and so on. The Consul's "garden scene" in Chapter Five thus becomes an analogue to Joyce's Nighttown episode, and Lowry's dislocation of time, his recognition of what Costa elsewhere calls the "weight of the past", relates to Joyce's and Proust's.