Urbanlsatlon in Atlantlc EUROPE in the Lron AGE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Périmètre Des SPANC Périmètre Des Communes Compétences Du

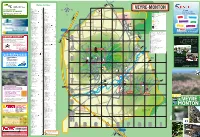

Lapeyrouse Compétences des Services Publics d'Assainissement Non collectifs (SPANC) Buxières-sous-Montaigut Ars-les-Favets Durmignat Département du Puy de Dôme Montaigut La Crouzille Saint-Éloy-les-MinesMoureuille Virlet Youx Servant Le Quartier Château-sur-Cher Pionsat Menat Saint-Hilaire Saint-Gal-sur-Sioule TeilhetNeuf-Église La Cellette Pouzol Saint-Quintin-sur-Sioule Périmètre des SPANC Saint-Maigner Sainte-Christine Saint-Rémy-de-Blot Marcillat Saint-Maurice-près-Pionsat Gouttières Bussières Ayat-sur-Sioule Champs Saint-Genès-du-Retz Périmètre des communes Saint-Pardoux Vensat Saint-Julien-la-Geneste Lisseuil Saint-Sylvestre-Pragoulin Effiat Saint-Hilaire-la-CroixSaint-Agoulin Roche-d'AgouxEspinasse Montpensier Bas-et-Lezat Blot-l'Église Chaptuzat Saint-Priest-Bramefant Compétences du SPANC Vergheas Châteauneuf-les-Bains Jozerand Saint-Gervais-d'Auvergne Villeneuve-les-Cerfs Montcel Aigueperse Randan Lachaux Artonne Bussières-et-Pruns Ris Saint-Angel Mons Contrôle Charensat Saint-Clément-de-Régnat Biollet Sauret-Besserve Charbonnières-les-Vieilles Beaumont-lès-Randan CombrondeSaint-Myon Vitrac Aubiat Limons Ü ThuretSaint-Denis-Combarnazat Châteldon Saint-Priest-des-ChampsQueuille Beauregard-Vendon Contrôle, Réhabilitation La Moutade Sardon Teilhède Le Cheix Luzillat Puy-Guillaume Davayat Saint-André-le-Coq Saint-Georges-de-MonsManzat Prompsat Cellule Charnat Montel-de-Gelat Loubeyrat Martres-sur-MorgeSurat Saint-Victor-Montvianeix Contrôle, Vidange, Réhabilitation Les Ancizes-Comps Saint-Bonnet-près-Riom Paslières Pessat-Villeneuve -

Classement Plateau Gergovie

PRÉFÈTE DU PUY-DE-DÔME Projet de site classé Plateau de Gergovie et des sites arvernes ----------- Délibérations des collectivités - Authezat (pas de délibération et avis tacite favorable) - Le Cendre - Chanonat - Corent - Le Crest - Les Martres-de-Veyre - Orcet - Pérignat-lès-Sarliève - La Roche Blanche - La Roche-Noire - Romagnat - La Sauvetat - Tallende - Veyre-Monton - Conseil régional Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes (pas de délibération et avis tacite favorable) - Conseil départemental du Puy-de-Dôme - Le Grand Clermont - Clermont Auvergne Métropole - Mond’Arverne communauté LE CENDRE DEPARTEMENT DU PUY-DE-DOME ARRONDISSEMENT DE CLERMONT-FERRAND EXTRAIT DU REGISTRE DES DELIBERATIONS DU CONSEIL MUNICIPAL Date de la convocation : 19 mars 2019 Date et heure de la séance : 25 mars 2019 à 18h.30 Nombre de conseillers municipaux : 27 Nombre de présents : 22 Absents avecQ_rocuration :3 Absents: 2 Présents : M. Nicolas BERNARD - Mmes _Josiane BEUREL- Jacqueline BOUS - MM. Philippe CRESPIN - Pascal DE COTTE - Jacques DU BOISSET - Mme Sylvie FABRON - M. Jean-Pierre FASSIER - Mmes Adrienne UBIOUL - Marie-Christine MACARIO - Christel MARCHENAY - MM. Jean-Marc MIGUET - Jean-Louis MOLAT- M. Sébastien MORIN- Philippe PACHECO- Mme Sylvie PARIS - MM. Bruno PONTRUCHER - Jean-Paul PRESLE - Hervé PRONONCE - Jean-François RAZAVET - Mmes Agnès ROCHE - Karine SOUCHAL. Absents avec procuration : M. Matthias DINIZ procuration à M. Jean-Paul PRESLE - Mme Martine LEGRAND procuration à Mme Jacqueline BOUS - Mme Valérie MONTEIRO procuration à Mme Adrienne UBIOUL. Absents : Mmes Ludivine MEISSONNIER - Nadège PARANT. Secrétaire de séance : Mme Karine SOUCHAL. Président de séance : M. Hervé PRONONCE. 1 N° 19/03/25/003 OBJET : Projet de site classé du plateau de Gergovie et des sites arvernes : avis du Conseil Municipal. -

T-Fd Vic-Le-Comte

4040 VIC-LE-COMTEVIC-LE-COMTE - -MIREFLEURS MIREFLEURS - -CLERMONT CLERMONT-FD-FD VIC-LE-COMTEVIC-LE-COMTE - COURNON- COURNON (L (Lycéeycée Descartes) Descartes) TransporteurTransporteur KEOLISKEOLIS LOISIRS LOISIRS & &VOY VOYAGESAGES - 04- 04 73 73 69 69 96 96 96 96 JouJrosudrsedceirccuirlcautiloantion JouJrosudrsedceirccuirlcautiloantion LMLMMeMe JVSJVS VIC-LE-COMTE - MIREFLEURS CirCcuirlceu elen e pné priéordioedsecosclaoirleaire CirCcuirlceu elen e pné priéordioedsecosclaoirleaire ouoi ui CirCcuirlceu elen e pné priéordioeddeed vea cvaanccaensces CirCcuirlceu elen e pné priéordioeddeedveacvaanccaensces CLERMONT-FD RenvoisRenvois à consulte à consulter r 5 5 5 5 RenvoisRenvois à consulte à consulter r VICV-ILCE--LCEO-CMOTME TE VICV-ILCE--LCEO-CMOTME T(E C(OECLOE LPER IPMRAIMIRAEI)RE) 07.0175.15 LONLOGNUGESU ES LONLOGNUGESU E(LES (LEPLANA PLANAT) (Vic-le-Comte)T) (Vic-le-Comte) 07.1807.18 VIC-LE-COMTE - COURNON MIREFLEURSMIREFLEURS (R. (R.CHAMPS CHAMPS DE DELA LAREINE) REINE) LONGUESLONGUES(PA(PTISSERIE)ATISSERIE) (Vic-le-Comte) (Vic-le-Comte) 07.2007.20 MARTRES-DE-VEYREMARTRES-DE-VEYRE (CARREFOUR (CARREFOUR) ) LONLOGNUGESU E(GARES (GARE SNCF) SNCF) (Vic-le-Comte) (Vic-le-Comte) 07.2107.21 MARTRES-DE-VEYREMARTRES-DE-VEYRE (SNCF) (SNCF) MAMRTARRETSR-EDSE--DVEE-YVREEY (RTERE (RTE DE DECORENT) CORENT) 07.2407.24 LE CENDRELE CENDRE(CROIX(CROIX DU DUCHRIST CHRIST) ) MIRMEFIRLEFULRESU (CHAMPRS (CHAMP DE DELA REINELA REINE) ) 07.3007.30 ORCETORCET (MOULIN) (MOULIN) MAMRTARRETSR-EDSE--DVEE-YVREEY (GARERE (GARE SNCF SNCF) ) 07.3507.35 ORCETORCET (BOURG) (BOURG) COURNONCOURNON (COLLÈGE (COLLÈGE LA RIBEYRE)LA RIBEYRE) 07.4507.45 ORCETORCET (CROIX (CROIX GUILLAUME) GUILLAUME) COURNONCOURNON (LYCÉE (LYCÉE DESCARTES) DESCARTES) 07.5007.50 40 ORCETORCET (PERCEDES (PERCEDES) ) ORCETORCET (R. POR(R. PORTAL)TAL) 07.0307.03 AUBIEREAUBIERE (Roussillon (Roussillon) ) 09.4009.40 CLERMONCLERMONT-FDT- FD(Margeride) (Margeride) 07.1307.13 09.4309.43 CLERMONTCLERMONT-FD-FD (ESPLANADE) (ESPLANADE) CLERMONTCLERMONT-FD-FD (G. -

Contextes Piscicoles Du Bassin De La Seille En Saône-Et-Loire

PLAN DEPARTEMENTAL POUR LA PROTECTION DES MILIEUX AQUATIQUES ET LA GESTION DES RESSOURCES PISCICOLES DE SAONE-ET-LOIRE DIAGNOSTICS MILIEUX ET PISCICOLES Contextes piscicoles du bassin de la Seille en Saône-et-Loire TABLE DES MATIERES 1. PRESENTATION DES CONTEXTES PISCICOLES .......................................................................................... 1 2. DIAGNOSTIC MILIEUX .............................................................................................................................. 3 A. QUALITE PHYSICO‐CHIMIQUE ............................................................................................................. 3 CONTEXTE GIZIA : ........................................................................................................................................ 4 CONTEXTE SOLNAN : ................................................................................................................................... 4 CONTEXTE BRENNE : ................................................................................................................................... 5 CONTEXTE SEILLE AVAL : ............................................................................................................................. 6 B. REGIME THERMIQUE ........................................................................................................................... 7 CONTEXTE GIZIA : ....................................................................................................................................... -

Tableaux Conseillers Municipaux Et Communautaires

TABLEAU II des communes du département du PUY-DE-DOME comptant moins de 1 000 habitants au 1er janvier 2014 annexé à l'arrêté préfectoral n° 2014/PREF63/14/000 51 du 14 janvier 2014 A B C DE population Nombre de nombre de sièges Arrondissement Communes municipale conseillers de conseiller au 01/01/14 municipaux communautaire Ambert AIX LA FAYETTE 71 7 1 Ambert AUZELLES 349 11 2 Ambert BAFFIE 117 11 2 Ambert BERTIGNAT 475 11 3 Ambert BEURRIERES 305 11 3 Ambert BROUSSE 357 11 2 Ambert LE BRUGERON 251 11 3 Ambert CHAMBON SUR DOLORE 170 11 2 Ambert CHAMPETIERES 253 11 2 Ambert LA CHAPELLE AGNON 383 11 2 Ambert LA CHAULME 132 11 2 Ambert CHAUMONT LE BOURG 223 11 3 Ambert CONDAT LES MONTBOISSIER 223 11 2 Ambert DORANGES 151 11 2 Ambert DORE L'EGLISE 625 15 4 Ambert ECHANDELYS 226 11 2 Ambert EGLISOLLES 264 11 2 Ambert FAYET RONAYE 101 11 1 Ambert LA FORIE 324 11 3 Ambert FOURNOLS 338 11 2 Ambert GRANDRIF 170 11 4 Ambert GRANDVAL 114 11 1 Ambert MARAT 836 15 4 Ambert MAYRES 180 11 2 Ambert MEDEYROLLES 114 11 2 Ambert LE MONESTIER 200 11 2 Ambert NOVACELLES 147 11 2 Ambert OLLIERGUES 746 15 4 Ambert SAILLANT 281 11 2 Ambert SAINT ALYRE D'ARLANC 168 11 2 Ambert SAINT AMANT ROCHE SAVINE 528 15 3 Ambert SAINT ANTHEME 736 15 3 Ambert SAINT BONNET LE BOURG 143 11 1 Ambert SAINT BONNET LE CHASTEL 229 11 2 Ambert SAINTE CATHERINE 59 7 1 Ambert SAINT CLEMENT DE VALORGUE 225 11 2 Ambert SAINT ELOY LA GLACIERE 62 7 1 Ambert SAINT FERREOL DES COTES 537 15 4 Ambert SAINT GERMAIN L'HERM 487 11 3 Ambert SAINT GERVAIS SOUS MEYMONT 264 11 3 Ambert SAINT JUST -

Auvergne-Rhone-Alpes Wine and Food Sales Manual

AUVERGNE-RHONE-ALPES WINE AND FOOD SALES MANUAL September 2019 Auvergne-Rhone-Alpes Tourisme – Wine and Food Sales Manual – September 2019 Page 1 Contents 1. Introduction to the wine areas of Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes Page 3 Key facts about wine tourism Page 3 Map Page 4 2. Main cellars and sites linked to the wine Page 5 Beaujolais Page 5 The Rhône Valley Page 8 The Savoie Wines Page 13 Vineyards well worth a visit Page 14 In “Bubbles” country Page 16 3. Vignobles & Découvertes quality label Page 17 4. Wine experts and local DMC’s Page 20 5. Transport and transfers Page 24 6. Focus on gastronomy Page 25 Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, the largest PDO cheeseboard in France Page 25 Top gastronomic sites Page 26 Vallée de la Gastronomie – France /Cité de la Gastronomie Lyon Page 27 A destination for top quality restaurants Page 28 7. Cooking and French pastry classes Page 30 8. Wine and Food main events and festivals Page 32 9. Accommodation in Lyon and the vineyards (see Attachment) Page 37 10. Useful contacts and information Page 37 NB. This Wine & Food Sales manual is a selection of the best wine-cellars, sites linked to wine, wine- experts, gastronomy and cooking classes able to welcome foreign visitors in the region. Auvergne-Rhone-Alpes Tourisme – Wine and Food Sales Manual – September 2019 Page 2 1. Introduction to the wine areas of Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes From the Alps to Provence, the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region is a land of exceptional diversity: alpine peaks, lush plateaux, great lakes and fields of lavender are the iconic landscapes which give the region its distinctive character. -

CONNECTING WORLDS BRONZE-AND IRON AGE DEPOSITIONS in EUROPE Dahlem TH ST Dorf BERLIN 19 -21 APRIL

CONNECTING WORLDS BRONZE-AND IRON AGE DEPOSITIONS IN EUROPE Dahlem TH ST Dorf BERLIN 19 -21 APRIL Ethnologisches Museum Dahlem Ethnologisches Museum Dahlem Lansstraße 8, 14195 Berlin U 3 direction: U Krumme Lanke to U Dahlem Dorf Ethnologisches Museum (Dahlem) Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Eurasien-Abteilung des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts Im Dol 2-6, D-14195 Berlin, www.dainst.org, Phone +49 30 187711-311 EURASIEN-ABTEILUNG CONNECTING WORLDS BRONZE-AND IRON AGE DEPOSITIONS IN EUROPE BERLIN 19TH-21ST APRIL Eurasien-Abteilung Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Berlin 2018 WELCOMING ADDRESS Preface On the occasion of the European Cultural Heritage Year (ECHY) 2018, which aims to make the shared European roots visible, the Eurasian Department of the German Ar- chaeological Institute organizes the conference Connecting worlds - Bronze and Iron Age depositions in Europe. Bronze Age and Early Iron Hoards and single depositions in rivers, lakes and bogs but also mountains and along old paths have been discussed over years. Whereas they were still in the 1970s considered as hidden treasures, in the last 30 years a lot of studies showed the regularities of hoard contents, the non-functional treatment of the objects and many other details which speak for ritual deposition. Meanwhile, most specialists would agree that if not all but the great majority of metal hoards was deposited by religious reasons in the broadest sense. This paradigm change makes Bronze Age hoards a cultural phenomenon which links most regions in Europe from the Atlantic to the Urals and to the Caucasus from Scan- dinavia to Greece between 2200 and 500 BC and in many regions also thereafter. -

Un Siècle En Paroles, Beaumont (Puy-De-Dôme)

BeaumontUn siècle en paroles (Puy-de-Dôme) Souvenirs d’habitants, 1910-2010 Préface Préambule Après les différents ouvrages consacrés au patrimoine Pour mieux connaître la communauté beaumontoise et – objectif à la beaumontois*, saluons cette nouvelle publication sur base de ce projet – la rémanence de « son » XXe siècle, rien de tel que la mémoire orale qui mérite d’être sauvegardée. d’aller à la rencontre de ses habitants, chez eux, de les entendre racon- « Chaque fois qu’un griot meurt, c’est toute une ter la vigne, la guerre, l’évolution urbaine et démographique depuis les bibliothèque qui disparaît », disait le poète africain. années 1920 jusqu’à aujourd’hui… Sans oublier de regarder les objets Coucher sur le papier ces souvenirs, qui balayent et les documents qu'ils acceptent de montrer, ce qui ajoute quelques des décennies de la vie de nos concitoyens, permet touches réalistes à des récits parfois incroyables aux oreilles les plus jeunes. Peu à peu, comme à la lecture d'un roman, un univers se des- de garder une trace de ceux qui, souvent anonymes, sine, avec son épaisseur, ses mystères et ses personnages… ont façonné notre ville. Pressentis par un comité de pilotage pluraliste et attentif, quarante et Bien entendu, les témoignages présentés ici sont un habitantes et habitants de Beaumont ont ainsi accepté de piocher incomplets, partiels et subjectifs ; seuls quelques-uns quelques heures dans leurs mémoires, et parfois leurs jardins secrets… d’entre nous ont été sollicités. Il ne s’agissait pas Tour à tour souriantes, émues ou vibrantes, leurs voix ont mis en pers- de prétendre, en recueillant les propos de quarante pective le portrait d’une cité qui, en un siècle, a beaucoup changé mais et un habitants de Beaumont, anciens ou plus récents, gardé son charme et son âme : toujours riche de sa verdure et surtout à un travail exhaustif, pas plus qu’à une démarche scientifique accueillante, tant aux nouveaux venus de l’exode rural qu’aux immi- et historique, d’autant plus que les ouvrages précédents grés en mal de travail ou de liberté. -

Les Mesures D'urgence

Gestion des épisodes de pollution de l’air en Auvergne LES MESURES D’URGENCE CommuniquéEn cas du de XX déclenchement XX 20XX 12h00 de la procédure d’ ALERTE valable pour les prochaines 24h Procédure d’alerte de NIVEAU 1 Sur la zone définie pour le(s) département(s) concerné(s) (cf listes en pages 3 à 5) : ● Réduction de 20 km/h de la vitesse maximale autorisée sur l’ensemble des voies de circulation routière et autoroutière où la vitesse maximale autorisée est supérieure ou égale à 90 km/h. Des contrôles de vitesse et de pollution des véhicules seront effectués par les forces de l’ordre. Sur l’ensemble du/des département(s) concerné(s) : ● Interdiction de tous les feux de plein air et notamment des écobuages (suspension des dérogations) et des feux d’agrément utilisant un combustible solide ; ● Mise en place des mesures prévues pour les aéronefs et dans les arrêtés d’autorisation des industries concernées ; ● uniquement pour les épisodes de pollution « ozone » : Interdiction de certains chargements et déchargements de produits émettant des composés organiques volatils (COV). _____________________________________________ Procédure d’alerte de NIVEAU 2 Sur la zone définie pour le(s) département(s) concerné(s) (cf listes en pages 3 à 5) : ● Réduction de 20 km/h de la vitesse maximale autorisée sur l’ensemble des voies de circulation routière et autoroutière où la vitesse maximale autorisée est supérieure ou égale à 90 km/h. Des contrôles de vitesse et de pollution des véhicules seront effectués par les forces de l’ordre. Sur l’ensemble du/des -

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 B C D E F G H I 11 a Veyre Monton

RD 52 Vers CLERMONT-FERRAND Noms des rues Vers ORCET NUMÉRO 1 FRANÇAIS DES RÉSEAUX DE PROXIMITÉ A I Abbaye (chemin de l’) C8-C9 Issoire (route d’) D9-D10-E11 VEYRE-MONTON L’ASSOCIATION Déchetterie Acacias (chemin des) B6 L’eau J ROUTE Amandiers (chemin des) B5 16 DU SERVICE À DOMICILE Jardin (rue des) C6 (rue) F2 Source de vie Ampère Rue Pierre-Gilles de Gennes ADMR VEYRE AUZON - 1, RUE DE LA MAIRIE Jardin (chemin des) C6 Anciens Combattants (square des) E6 Routes départementales ou communales Source d’économie 63670 LA ROCHE BLANCHE - 04 73 79 80 56 Anglades (rue des) B6-C5 L Rue Edmé Chemins communaux Anglades (montée des) C5 Lacot (chemin de) D3 Mariotte Asphodèles (rue des) B7-C7 Lamartine (allée) E8-F8 Voies piétonnes Fosse Récupération Astragale (chemin de l’) E6 Lavoir (chemin du) C5 Sentiers DE septique d’eau de pluie Lilas (allée des) C6-C7 Rue Augustin Aubépines (allée des) B6-B7 de Coulomb Puy de TOBIZE Sens unique 1 CD 978 (place Lucie) C6 Lilas (impasse) C6 s 491 m Aubrac t Rue Ampère a Rue (rue Pierre) l Espaces verts Loti E8 P Gay-Lussac ZAC du Pra de Serre Assainissement Vers CLERMONT-FERRAND Rétention A 75 s Faraday B Rue CD 213 e Bâtiments publics d CLERMONT Individuel / Collectif (montée du) C5 M d’eau Bailly n i Zones d’activités Balzac (rue Honoré de) F8 Madéore (place Joseph) G8 m 11 e Rue Léon S h e Magnolias (allée des) F6 C r Barry (impasse du) C5 Rue Jules p Pompe de Rue René Dutrocheto 2 Aires de jeux Pelouze ll Mandonnet (pl. -

Secteurs Géographiques

Secteurs géographiques LAPEYROUSE St-ELOY-les-MINES BUXIERES-sous- Puy-de-Dôme ARS-les-FAYETS MONTAIGUT DURMIGNAT MONTAIGUT-en- COMBRAILLES La CROUZILLE St-ELOY-les-MINES MOUREUILLE VIRLET AIGUEPERSE SERVANT YOUX Le QUARTIER CHATEAU-sur- PIONSAT CHER St-GAL- MARINGUES MENAT sur-SIOULE St-HILAIRE TEILHET NEUF-EGLISE La CELLETTE POUZOL St-QUINTIN- sur-SIOULE St-MAGNIER St-REMY-de-BLOT MARCILLAT Ste-CHRISTINE St-MAURICE- GOUTTIERES St-GENES- près-PIONSAT BUSSIERES CHAMPS St-GERVAIS-d’AUVERGNE St-JULIEN AYAT-sur- SIOULE du-RETZ -la-GENESTE LISSEUIL St-PARDOUX VENSAT St-SYLVESTRE- St-HILAIRE- PRAGOULIN RIOM EFFIAT BAS-et-LEZAT la-CROIX St-AGOULIN MONTPENSIER ROCHE d’AGOUX CHATEAUNEUF- St-PRIEST- ESPINASSE les-BAINS BLOT-l’EGLISE CHAPTUZAT JOSERAND BRAMEFANT VERGHEAS St-GERVAIS- VILLENEUVE AIGUEPERSE d’AUVERGNE MONTCEL -les-CERFS RANDAN BUSSIERES- RIS ARTONNE et-PRUNS MONS St-ANGEL BEAUMONT- St-CLEMENT- LACHAUX BIOLET les-RANDAN SAURET- CHARBONNIERES de-REIGNAT CHARENSAT St-MYON BESSERVE -les-VIEILLES COMBRONDE St-DENIS- LIMONS VITRAC AUBIAT COMBARNAZAT QUEUILLE THURET CHATELDON BEAUREGARD- St-PRIEST-des- THIERS PONTGIBAUD VENDON SARDON St-ANDRE LUZILLAT PUY-GUILLAUME TEILHEDE Le CHEIX- CHAMPS CHAMBARON- sur-MORGE -le-COQ MANZAT sur-MORGE GIMEAUX CHARNAT PROMPSAT DAVAYAT St-GEORGES- VARENNES- SURAT St-VICTOR- Le MONTEL- LOUBEYRAT sur-MORGE Les MARTRES- MONTVIANEIX de-MONS YSSAC-la-TOURETTE sur-MORGE de-GELAT Les ANCIZES- St-BONNET- PESSAT- VINZELLES PASLIERES COMPS près-RIOM VILLENEUVE MARINGUES NOALHAT VILLOSANGES St-IGNAT MIREMONT CHATEL-GUYON -

Bulletin Municipal N°70

ROMAGNAT info Dossier du mois : • Le nouveau service éducation, jeunesse, sports, culture et vie associative Bulletin Municipal - n° 70 - mars 2010 Bulletin Municipal n°70 Directeur de la publication : FRANÇOIS FARRET, Maire Coordination : FRANÇOIS E CHAPUT Réalisation : Service Communication Comité de lecture : RÉMY SERPOLAY, PA ul SUTEAU, AL B E R T ODOUARD, AN D RÉ E HUGOND, MARI E ‑HÉ L ÈN E DAUPLAT, JA C Q ue S SCHNEIDER Impression : Imprimerie SIC 7, rue Joseph Desaymard - ZAC La Pardieu 63000 CLERMONT-FERRAND Imprimé sur papier recyclé Cyclus Print, sous le label IMPRIM’ VERT® N° ISSN : 1283 - 5080 Tiré à 4100 exemplaires 3 édito Distribué par la société ADREXO CONSEIL MUNICIPAL 4 évènements marquants Maire : FRANÇOIS FARRET 1er Adjoint : MARI E -FRANÇOIS E BERKANI eme 6 dossier du mois 2 Adjoint : FRANÇOIS RITROVATO 3eme Adjoint : BE RNAD ette ROUX 4eme Adjoint : JE AN -CLA U D E BENAY 5eme Adjoint : MARI E -CHRIS T IN E GIRAUD 19 économie 6eme Adjoint : JE AN -MI C H E L LAUMONT 7eme Adjoint : FRANÇOIS E CHAPUT 8eme Adjoint : JE AN -MA X BOURLIER 20 informations municipales Conseillers Délégués : AL be R T ODOUARD, NA ym A GUERMITE, libre expression AN T ONIO NEVES, RÉ my SERPOLAY, 22 FA T I M A RATURAS, MI C H E L JOACHIN, PA T RI ck CRESSEIN, Guy DOR, PA U L SUTEAU. 24 informations municipales (suite) Conseillers Municipaux : LA U R E N ce MIOCHE-JACQUESSON, 27 vie associative BRI G I tte PALLUT, CLA U D E PRADEL, MARI E BRIQUET, MARI E FERREIRA, JA cque S SCHNEIDER, 40 infos sociales MARI E -JE ANN E GILBERT, GILL E S VAUCLARD, MAR T IN E ARNAL, FRÉDÉRI C SIEGRIST, 41 divers MARI E -HÉLÈN E DAUPLAT.