Molly Hankwitz Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HAC022708 1.Pdf

Federal Communications Commission FCC 08-67 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Section 68.4(a) of the Commission’s Rules ) Governing Hearing Aid-Compatible Telephones ) WT Docket No. 01-309 ) Petitions for Waiver of Section 20.19 of the ) Commission’s Rules ) ) ) MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER Adopted: February 26, 2008 Released: February 27, 2008 By the Commission: TABLE OF CONTENTS Heading Paragraph # I. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................. 1 II. BACKGROUND.................................................................................................................................... 3 III. DISCUSSION ........................................................................................................................................ 9 A. Waiver Requests from Tier III Carriers ........................................................................................... 9 1. CDMA and GSM Carriers....................................................................................................... 10 a. Advantage, BLEW, Brazos, Cellcom, FMTC Mobile, Inland, Lamar, Mid-Tex, MTPCS, NCR1P, Nemont, NTCH, NWMC, Peoples, Plateau, Pocket, Simmetry, South Central, Thumb, West Central, and XIT................................................................. 11 b. Airadigm, Blanca, CTC, Farmers Cellular, Litchfield, NDNC, PTSI, South Slope, and UBET Wireless .............................................................................................. -

Wireless Call Trace Procedure Version 2.4

Document date: 07/01/2011 Wireless Call Trace Procedure Version 2.4 Prepared by: Systems 3/7/06 Revised 12/30/14 Page 1 of 8 Document date: 07/01/2011 Purpose of Document The following document establishes a procedure for obtaining tower or subscriber information for wireless 9-1-1 calls. This procedure may be used in the event the caller has been disconnected and is believed to be in an emergency situation where the billing information (often the home address) may provide the location of the caller. For example, a call is received where a person is screaming hysterically and then is suddenly disconnected. If the dispatcher is unable to reach the caller by using the call back number they may choose to use this procedure. Following this procedure, a dispatcher can use the callback number provided on the ALI screen to obtain the home address of the person who owns that phone in hopes of obtaining further information on where the caller may be located. Definitions This policy applies only to wireless 9-1-1 calls and not wireline 9-1-1 calls. For the purposes of this document, the terms below are defined as follows; Subscriber Information Number : This number will provide you with subscriber name, billing address, home number, and other identifying information. In the event the Subscriber Information Number listed in this policy is not correct, contact the NOC to obtain a contact number for subscriber information. Please notify S911D for update of this document. NOC Number : This number will provide you with tower location information. -

Telecommunications Service Providers IAC Codes, Exchange Carrier Names, Company Codes - Telcordia and Regions

COMMON LANGUAGE® Telecommunications Service Providers IAC Codes, Exchange Carrier Names, Company Codes - Telcordia and Regions Telcordia Technologies Practice BR-751-100-112 Issue 2 April 1999 Proprietary — Licensed Material Possession or use of this material or any of the COMMON LANGUAGE Codes, Rules, and Information disclosed herein requires a written license agreement and is governed by its terms and conditions. For more information, visit www.commonlanguage.com/notices. An SAIC Company BR-751-100-112 TSP IAC Codes, EC names, Company Codes - Telcordia and Regions Issue 2 Copyright Page April 1999 COMMON LANGUAGE® Telecommunications Service Providers IAC Codes, Exchange Carrier Names, Company Codes - Telcordia and Regions Prepared for Telcordia Technologies by: Lois Modrell Target audience: Telecommunications Service Providers This document replaces: BR-751-100-112, Issue 1, March 1998 Technical contact: Lois Modrell To obtain copies of this document, contact your company’s document coordinator or call 1-800-521-2673 (from the USA and Canada) or 1-732-699-5800 (all others), or visit our Web site at www.telcordia.com. Telcordia employees should call (732) 699-5802. Copyright © 1997-1999 Telcordia Technologies, Inc. All rights reserved. Project Funding Year: 1999 Trademark Acknowledgments Telcordia is a trademark of Telcordia Technologies, Inc. COMMON LANGUAGE is a registered trademark of Telcordia Technologies. Proprietary — Licensed Material See confidentiality restrictions on title page. 2 BR-751-100-112 Issue 2 TSP IAC Codes, EC Names, Company Codes - Telcordia and Regions April 1999 Disclaimer Notice of Disclaimer This document is issued by Telcordia Technologies, Inc. to inform Telcordia customers of the Telcordia practice relating to COMMON LANGUAGE® Telecommunications Service Providers IAC Codes, Exchange Carrier Names - Company Codes - Telcordia and Regions. -

NENA Standard for 9-1-1 Call Processing

NENA Standard for 9-1-1 Call Processing Abstract: This NENA Standard document is intended to provide a model standing operating procedure (SOP) for the handling of calls received by Public Safety Answering Points (PSAPs) and to ensure consistency in the processing of emergency and non- emergency calls across jurisdictional boundaries. The document provides guidance to implementing the standard’s normative requirements as well as recommendations for those operational call handling areas that should be governed by local policy. NENA Standard for 9-1-1 Call Processing NENA-STA-020.1-2020 (combines 56-001, 56-005, 56,006 and 56-501) DSC Approval: 03/31/2020 PRC Approval: 04/10/2020 NENA Executive Board Approval: 04/16/2020 Next Scheduled Review Date: 10/16/2020 Prepared by: National Emergency Number Association (NENA) PSAP Operations Committee, 9-1-1 Call Processing Working Group Published by NENA Printed in USA © Copyright 2020 National Emergency Number Association, Inc. NENA Standard for 9-1-1 Call Processing NENA-STA-020.1-2020 (combines 56-001, 56-005, 56,006 and 56-501), April 16, 2020 1 Executive Overview This standard has been developed to facilitate the processing of 9-1-1 calls by Public Safety Answering Points (PSAPs) and to serve as a basis for the development of Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs). Use of this document standardizes the method of call handling across jurisdictional boundaries. This will provide consistency in the processing of emergency and non-emergency calls and improve service to the public. Over the course of the past decade, NENA published a number of Operational Standards and Information Documents that discuss the handling and processing of 9-1-1 calls. -

MVNO Seminar.PDF

MVNO Seminar Washington DC Paris Tokyo www.thebesengroup.com Overview Our MVNO seminar is the most comprehensive seminar of its kind in the world. It will help you stay ahead of your competition and become one of the most successful MVNOs in the mobile market. Whether you want to brush up on MVNO fundamentals or get a thorough business overview, we cover both and more. With our seminar, you will learn different strategies from 53 specific MVNO case studies spanning over 26 different categories and also learn how to build a compelling voice and data centric MVNO business case. Our ultimate goal is to maximize your knowledge and answer all of your MVNO questions. Depending on your needs, we can also customize the seminar to fit your particular situation. Definitions MNO: It is a mobile network operator that owns its mobile network infrastructure and allocation of spectrum. It does not open its network to MVNOs, MVNAs and may work with multiple MVNEs. HNO: It is as a mobile network operator that owns its network infrastructure and allocation of spectrum. It opens its network to MVNOs, MVNAs, and may work with multiple MVNEs. MVNO: It is an organization that offers mobile and mobile data services with or without spectrum. Note that the spectrum can be licensed or unlicensed. It may work with multiple HNOs, MVNAs, MVNEs. MVNA: It is an organization that combines multiple MVNOs and may work with multiple HNOs, and MVNEs. MVNE: It is an intermediary organization that offers managed services and may work with multiple MNOs, HNOs, MVNEs, and MVNAs. -

Federal Communications Commission Response to United States House

Federal Communications Commission Response to United States House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce Universal Service Fund Data Request of June 15, 2010 Part 3 Largest Per-Line Subsidies, by Study Area Study Areas with the Highest Support per Line in 2009 Lines Support Rank Incumbent ETC State Holding Company1 Support2 (average3) per Line 1 WESTGATE COMMUNICATIONS LLC D/B/A WEAVTEL Washington Westgate Communications LLC $301,966 17 $17,763 2 ADAK TEL UTILITY Alaska Adak Eagle Enterprises, LLC $2,198,444 171 $12,894 3 BORDER TO BORDER Texas Border to Border Communications, Inc. $1,773,185 139 $12,757 4 BEAVER CREEK TELEPHONE COMPANY Washington May, Bott et al. $338,910 29 $11,892 5 SANDWICH ISLES COMM. Hawaii Sandwich Isles Communications, Inc. $23,945,376 2,192 $10,926 6 ACCIPITER COMM. Arizona Accipiter Communications, Inc. $3,007,000 318 $9,471 7 ALLBAND COMMUNICATIONS COOPERATIVE Michigan Allband Communications Cooperative $797,972 115 $6,969 8 TERRAL TEL CO Oklahoma Terral Telephone Company $1,614,582 246 $6,563 9 SOUTH PARK TEL. CO. Colorado American Broadband Communications et al. $1,086,314 177 $6,137 10 S. CENTRAL TEL - OK Oklahoma South Central Telephone Association, Inc. $1,836,062 303 $6,070 1 Holding company name indicates common control/common ownership of carriers. 2 Calendar year disbursements include prior period adjustments. 3 The average number of lines in 2009 was calculated by averaging the number of lines at the end of years 2008 and 2009. Because year-end 2009 line counts have not yet been filed with the Commission, the number of lines at the end of 2009 was estimated using a straight-line projection of data from 2004 to 2008. -

Report to the Community Is Courtesy of Jerry’S Printing Service

REPORT TO THE Grant Llewellyn, Music Director COMMUNITY North Carolina’s state orchestra, an orchestra achieving the highest level of artistic 2017 quality and performance standards, and embracing our dual legacies of statewide service and music education. Dear Friends, Orchestral music is thriving in our state: Over the past year, North Carolinians in 91 counties connected with the music-making of the North HOW OUR 84TH YEAR Carolina Symphony. More than 250,000 people—of all ages and walks of life—filled concert halls, libraries, restaurants, and gymnasiums, finding STACKED UP knowledge, inspiration, and joy through our performances. NCS is an artistic treasure, but it is also a vibrant, collaborative organization for North Carolina that matters to people in every corner of the state. Our community roots have grown deeper through ever-strengthening partnerships with fellow institutions, from school Thousands of Millennials and systems to museums, creating an impact greater than the sum of the parts as we work together to embrace and shape North Carolina life and culture. Gen X-ers at the Symphony— The Symphony’s national footprint has expanded as well; our March 2017 appearance at the 18,500 miles traveled 40% of ticket-buyers prestigious SHIFT festival in Washington, D.C., garnered praise from The Washington Post and The throughout North Carolina New York Times. And, our dedication to our home-state couldn’t be missed—each of the works we and beyond performed had ties to North Carolina. Reflecting on remarkable successes on and off the stage in the 2016/17 season, I feel confident Concerts and events that we have met the goals set forth in our strategic plan five years ago. -

Outline of CTIA – the Wireless Association's Comments on The

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, DC 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Skype Communications S.A.R.L. ) ) Petition to Confirm A Consumer’s Right to ) RM-11361 Use Internet Communications Software and ) Attach Devices to Wireless Networks ) ) ) ) OPPOSITION OF CTIA – THE WIRELESS ASSOCIATION® CTIA – THE WIRELESS ASSOCIATION® Appendices Provided By: 1400 16th Street, NW Suite 600 Washington, D.C. 20036 Willkie Farr & Gallagher (202) 785-0081 AEI-Brookings Joint Center for Michael F. Altschul Regulatory Studies Senior Vice President, General Counsel Christopher Guttman-McCabe Charles L. Jackson Vice President, Regulatory Affairs Paul W. Garnett Phoenix Center for Advanced Legal & Assistant Vice President, Regulatory Affairs Economic Public Policy David J. Redl Counsel, Regulatory Affairs WILEY REIN LLP 1776 K Street, NW Washington, DC 20006 (202) 719-7000 R. Michael Senkowski Bennett L. Ross Scott Delacourt Its Attorneys Submitted: April 30, 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................2 II. SKYPE’S PETITION FUNDAMENTALLY MISCHARACTERIZES THE STATE OF THE WIRELESS MARKETPLACE ....................................5 A. Wireless Carriers Compete With Other Media and Each Other for Subscribers .............................................................................................................5 B. Wireless Carriers Also Compete on Services and Quality of Service.............15 C. Consumers Also Benefit From Robust Competition Between -

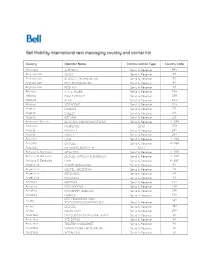

Country Operator Name Communication Type Country Code

Country Operator Name Communication Type Country Code Abkhazia A-MOBILE Send & Receive 995 Afghanistan AWCC Send & Receive 93 Afghanistan ETISALAT AFGHANISTAN Send & Receive 93 Afghanistan MTN AFGHANISTAN Send & Receive 93 Afghanistan ROSHAN Send & Receive 93 Albania A M C MOBIL Send & Receive 355 Albania EAGLE MOBILE Send & Receive 355 Albania PLUS Send & Receive 355 Albania VODAFONE Send & Receive 355 Algeria MOBILIS Send & Receive 213 Algeria DJEZZY Send & Receive 213 Algeria NEDJMA Send & Receive 213 American Samoa BLUE SKY COMMUNICATIONS Send & Receive +1-684 Andorra MOBILAND Send 376 Angola MOVICEL Send & Receive 244 Angola UNITEL Send & Receive 244 Anguilla LIME Send & Receive +1-264 Anguilla DIGICEL Send & Receive +1-264 Anguilla WEBLINKS ANGUILLA Send 1 Antigua & Barbuda APUA PCS Send & Receive +1-268 Antigua & Barbuda DIGICEL ANTIGUA & BARBUDA Send & Receive +1-268 Antigua & Barbuda LIME Send & Receive +1-268 Argentina CLARO ARGENTINA Send & Receive 54 Argentina NEXTEL ARGENTINA Send & Receive 54 Argentina PERSONAL Send & Receive 54 Argentina MOVISTAR Send & Receive 54 Armenia ARMGSM Send & Receive 374 Armenia MTS ARMENIA Send & Receive 374 Armenia KARABAKH TELECOM Send & Receive 374 Armenia ORANGE Send & Receive 374 DTH TELEVISION AND Aruba 297 TELECOMMUNICATIONS N.V. Send & Receive Aruba DIGICEL Send & Receive 297 Aruba SETAR GSM Send & Receive 297 Australia HUTCHISON 3G AUSTRALIA PTY Send & Receive 61 Australia YES OPTUS Send & Receive 61 Australia TELSTRA MOBILENET Send & Receive 61 Australia VIRGIN MOBILE(AUSTRALIA) Send -

751-100-112 Issue 4, April 2002

COMMON LANGUAGE® General Codes−Telecommunications Service Providers IAC Codes, Exchange Carrier Names, Company Codes− Telcordia and Regions Telcordia Technologies Practice BR-751-100-112 Issue 4, April 2002 Proprietary — Licensed Material Possession and/or use of this material or any of the COMMON LANGUAGE® Product Codes, Rules, and Information disclosed herein requires a written license agreement and is governed by its terms and conditions. For more information, visit www.commonlanguage.com/ notices. An SAIC Company BR-751-100-112 TSP IAC Codes, EC Names, Company Codes−Telcordia and Regions Issue 4, April 2002 Copyright Page COMMON LANGUAGE® General Codes−Telecommunications Service Providers IAC Codes, Exchange Carrier Names, Company Codes−Telcordia and Regions Prepared for Telcordia Technologies by: Lois Modrell, [email protected] Target audience: Telecommunications Service Providers This document replaces: BR-751-100-112, Issue 3, July 2000 Technical contact: Lois Modrell, [email protected] To obtain copies of this document, contact your company’s document coordinator or your Telcordia account manager, or call 1.800.521.2673 (from the USA and Canada) or +1.732.699.5800 (all others), or visit our Web site at http://www.telcordia.com. Telcordia employees should call 1.732.699.5802. Copyright © 1997-2002 Telcordia Technologies, Inc. All rights reserved. Trademark Acknowledgments Telcordia is a trademark of Telcordia Technologies, Inc. COMMON LANGUAGE is a registered trademark of Telcordia Technologies, Inc. Proprietary — Licensed Material See proprietary restrictions on title page. ii BR-751-100-112 Issue 4, April 2002 TSP IAC Codes, EC Names, Company Codes−Telcordia and Regions Notice of Disclaimer Notice of Disclaimer This document is issued by Telcordia Technologies, Inc. -

A Historical and Critical Study of Browning's Asolando Volume

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 3-1961 A Historical and Critical Study of Browning's Asolando Volume Paulina Estella Buhl University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Buhl, Paulina Estella, "A Historical and Critical Study of Browning's Asolando Volume. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 1961. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/2989 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Paulina Estella Buhl entitled "A Historical and Critical Study of Browning's Asolando Volume." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. Kenneth L. Knickerbocker, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Alwin Thaler, Bain T. Stewart, Reinhold Nordsieck, LeRoy Graf Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Copyl'ight by PAULINA ESTELLA BUHL 1961 March 2, 1961 To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Paulina Estella Buhl entitled 11A Historical and Critical Study of Browning's Asolando Volume ." I reconunend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the require ments for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. -

The Sou'wester Vol

The Sou'wester Vol. 80 No. 28 Rhodes College Wednesday, March 24, 1993 M Scholars Have Party To Benefit Disabled by Emily Flinn Scholars, as well as other Rhodes Staff Writer students who simply came and joined On Saturday, March 20, a party was in the fun. The students mingled with held in the pub for a group of people the visitors, introducing themselves with physical disabilities. The party and getting to know one another. was hosted by Bonner Scholars and Games were played to help break the Day Scholars from Rhodes, in con- ice and introduce everyone, and there junction with the Memphis Center for was even "Sit down Square Danc- Independent Living. ing," in which everyone could par- The Center, which began operating ticipate without even standing up. eleven years ago, is a nonprofit group Everyone enjoyed the music provid- which seeks to aid people with ed by singer/guitarists Turner and disabilities in fully integrating their White. lives into the community at large. The party helped to make many They provide information and refer- students aware of the difficulties for rals on resources available to people people with disabilities. Many with disabilities, on everything from buildings, including some of the older making a home wheelchair accessible ones on Rhodes campus, are not easi- to securing employment. The center ly accessible to people with also offers support programs, in- disabilities, especially those who use cluding the PALs program, in which wheelchairs. The restrooms in Hassell a child is paired with an adult with a Hall had to be used, since the ones in The new mail services policy might make this site even more common.