A Joint Call for Action Before a Major Regional Humanitarian Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Annual Report MARSHAL MARIA Mckee Swearing in Service

Committed To Excellence, Professionalism and Justice Fulton County Marshal’s Department 2020 Annual Report MARSHAL MARIA McKEE Swearing In Service TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome to our 14th Marshal, Maria McKee ..................Inside Front Cover Message from the Marshal ............................................... 4 Marshal Maria McKee’s Biography ........................................ 5 Marshal’s Command Staff ............................................... 6 Organization Chart ..................................................... 7 Reports ..............................................................8-9 Community Engagement ............................................. 10-12 New Employees Spotlight ................................................13 Wellness and Training ..................................................14 Training – Use of Force ..................................................15 Service Awards and Promotions ..........................................16 Recognitions 2020 ......................................................17 arshal Maria McKee was appointed by the Fulton County State Court F.O.C.U.S. Award .......................................................18 Bench and sworn in on December 19, 2019. She is M Men and Women of FCMD ..............................................19 the 14th Marshal of Fulton County and 2nd female to hold this position. Marshal McKee officially Back Cover ........................................................... 20 began her term as Marshal on January 1, 2020. In her new role -

the Lawmen: United States Marshals and Their Deputies

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. - . - --- ,-. - .- I. '. ., ~ ., •• ~~~'r,I. ... ... " \~\~"5cc .. ,.~ . The Lawmen: ~~ United States Marshals j, and Their Deputies hIt " " '0 1789 to ,the. Present L· -r = - t~. ' - -~ The Lawmen: United States Marshals t"" <t I .. " • I " and Their Deputies Ne3RS by \ MAR 12 1981 Frederick S. Calhoun, Historian, U.S. Marshals Service ACQUISHT10NS An overview of the origins and colorful history of the Nation's oldest, most distinguished federal law enforcement organization "For more than a century after the establishment of the fed eral government in 1789, U.S. Marshals provided the only nationwide civilian police power available to the president, Congress, and the courts. For two hundred years now, U.S. Marshals and their deputies have served as the instruments of civil authority used by all three branches of government. Marshals have been involved in most of the major historical episodes in America's past. The history of the marshals is. quite simply, the story of how the American people govern themselves. " This is an excerpt from the forthcoming official history of the U. S. Mar shals by Frederick S. Calhoun, Historian, U.S. Marshals Service. Mr. Calhoun, who received his Ph.D. from the University of Chicago, is the author of Power and Principle: Armed Intervention in Wilsonian Foreign Policy. 104856 J u.s. Department of JUstice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. -

US Military Ranks and Units

US Military Ranks and Units Modern US Military Ranks The table shows current ranks in the US military service branches, but they can serve as a fair guide throughout the twentieth century. Ranks in foreign military services may vary significantly, even when the same names are used. Many European countries use the rank Field Marshal, for example, which is not used in the United States. Pay Army Air Force Marines Navy and Coast Guard Scale Commissioned Officers General of the ** General of the Air Force Fleet Admiral Army Chief of Naval Operations Army Chief of Commandant of the Air Force Chief of Staff Staff Marine Corps O-10 Commandant of the Coast General Guard General General Admiral O-9 Lieutenant General Lieutenant General Lieutenant General Vice Admiral Rear Admiral O-8 Major General Major General Major General (Upper Half) Rear Admiral O-7 Brigadier General Brigadier General Brigadier General (Commodore) O-6 Colonel Colonel Colonel Captain O-5 Lieutenant Colonel Lieutenant Colonel Lieutenant Colonel Commander O-4 Major Major Major Lieutenant Commander O-3 Captain Captain Captain Lieutenant O-2 1st Lieutenant 1st Lieutenant 1st Lieutenant Lieutenant, Junior Grade O-1 2nd Lieutenant 2nd Lieutenant 2nd Lieutenant Ensign Warrant Officers Master Warrant W-5 Chief Warrant Officer 5 Master Warrant Officer Officer 5 W-4 Warrant Officer 4 Chief Warrant Officer 4 Warrant Officer 4 W-3 Warrant Officer 3 Chief Warrant Officer 3 Warrant Officer 3 W-2 Warrant Officer 2 Chief Warrant Officer 2 Warrant Officer 2 W-1 Warrant Officer 1 Warrant Officer Warrant Officer 1 Blank indicates there is no rank at that pay grade. -

Equivalent Ranks of the British Services and U.S. Air Force

EQUIVALENT RANKS OF THE BRITISH SERVICES AND U.S. AIR FORCE RoyalT Air RoyalT NavyT ArmyT T UST Air ForceT ForceT Commissioned Ranks Marshal of the Admiral of the Fleet Field Marshal Royal Air Force Command General of the Air Force Admiral Air Chief Marshal General General Vice Admiral Air Marshal Lieutenant General Lieutenant General Rear Admiral Air Vice Marshal Major General Major General Commodore Brigadier Air Commodore Brigadier General Colonel Captain Colonel Group Captain Commander Lieutenant Colonel Wing Commander Lieutenant Colonel Lieutenant Squadron Leader Commander Major Major Lieutenant Captain Flight Lieutenant Captain EQUIVALENT RANKS OF THE BRITISH SERVICES AND U.S. AIR FORCE RoyalT Air RoyalT NavyT ArmyT T UST Air ForceT ForceT First Lieutenant Sub Lieutenant Lieutenant Flying Officer Second Lieutenant Midshipman Second Lieutenant Pilot Officer Notes: 1. Five-Star Ranks have been phased out in the British Services. The Five-Star ranks in the U.S. Services are reserved for wartime only. 2. The rank of Midshipman in the Royal Navy is junior to the equivalent Army and RAF ranks. EQUIVALENT RANKS OF THE BRITISH SERVICES AND U.S. AIR FORCE RoyalT Air RoyalT NavyT ArmyT T UST Air ForceT ForceT Non-commissioned Ranks Warrant Officer Warrant Officer Warrant Officer Class 1 (RSM) Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force Warrant Officer Class 2b (RQSM) Chief Command Master Sergeant Warrant Officer Class 2a Chief Master Sergeant Chief Petty Officer Staff Sergeant Flight Sergeant First Senior Master Sergeant Chief Technician Senior Master Sergeant Petty Officer Sergeant Sergeant First Master Sergeant EQUIVALENT RANKS OF THE BRITISH SERVICES AND U.S. -

Change/Add Major Or Dual Major Form

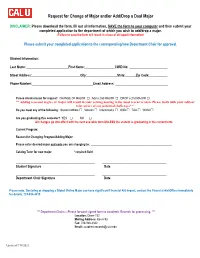

Request for Change of Major and/or Add/Drop a Dual Major DISCLAIMER: Please download the form, fill out all information, SAVE the form to your computer and then submit your completed application to the department of which you wish to add/drop a major. (Failure to save the form will result in a loss of all typed information) Please submit your completed application to the corresponding/new Department Chair for approval. Student Information: Last Name: First Name: CWID No: Street Address: City: State: Zip Code: Phone Number: Email Address: Please check reason for request: CHANGE OF MAJOR ☐ Add a 2nd MAJOR ☐ DROP a 2nd MAJOR ☐ *** Adding a second degree or major will result in your catalog moving to the most recent version. Please work with your advisor to be aware of any potential challenges*** Do you meet any of the following: Student Athlete ☐ Veteran ☐ International ☐ OSD ☐ TAA ☐ WIOA ☐ Are you graduating this semester? YES ☐ NO ☐ All changes go into effect with the next available term UNLESS the student is graduating in the current term. Current Program: _______________________________________________________________________________________ Reason for Changing Program/Adding Major: ________________________________________________________________ Please enter desired major and code you are changing to: ______________________________________________________ Catalog Term for new major: ______________* required field _____________________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Student Signature Date -

5 Regions of Virginia Bordering States Major Rivers & Cities Bordering

5 Regions of Virginia Bordering States West to East All Virginia Bears Play Tag Appalachian Plateau Valley & Ridge Never Taste Ketchup Without Mustard Blue Ridge Piedmont North Carolina Tidewater/Coastal Plain Tennessee Kentucky West Virginia Maryland Major Rivers & Cities Bordering Bodies of Water North to South Alex likes Potatoes Alexandria (and DC) are on the Potomac River. Fred likes to Rap Fredericksburg is on the Rappahannock River Chesapeake Bay Yorktown is on the York River Separates mainland Atlantic King James was Rich. VA and Eastern Shore Ocean Jamestown & Richmond are on the James River. Eastern Shore Rivers Eastern Shore Peninsula Flow into the Chesapeake Bay Source of food Pathway for exploration and settlement Chesapeake Bay Provided a safe harbor Was a source of food and transportation Atlantic Ocean Provided transportation Peninsula: links between Virginia and other places (Europe, Piece of land bordered by Africa, Caribbean) water on 3 sides Fall Line Tidewater - Coastal Plain Region Low, flat land; East of the Fall Land; Includes Eastern Shore; Natural Border between Waterfalls prevent near Atlantic Ocean and Chesapeake Bay Piedmont & Tidewater further travel on Regions the rivers. Piedmont Region Relative Location The mouse is next to the box. The ball is near the box. West of the Fall Line Means "Land at the Foot of the Mountain" Blue Ridge Mountain Region Valley and Ridge Region Old, Rounded Mountains West of Blue Ridge Region Source of Many Rivers Includes the Great Valley of Virginia Piedmont to East/Valley & Ridge to West Valleys separated by ridges Part of Appalachian Mountain System Part of Appalachian Mountain System Appalachian Plateau Region Plateau Area of elevated land that is flat on top Located in Southwest Virginia Only Small Part of Plateau Located in Virginia Dismal Swamp and Valley, Ridge Definition Lake Drummond Ridge: chain of hills Located in Tidewater/Coastal Plain Region Dismal Swamp: Surveyed by George Washington; lots of wildlife Lake Drummond: Shallow lake surrounded by Valley: land between hills swamp . -

Army Abbreviations

Army Abbreviations Abbreviation Rank Descripiton 1LT FIRST LIEUTENANT 1SG FIRST SERGEANT 1ST BGLR FIRST BUGLER 1ST COOK FIRST COOK 1ST CORP FIRST CORPORAL 1ST LEADER FIRST LEADER 1ST LIEUT FIRST LIEUTENANT 1ST LIEUT ADC FIRST LIEUTENANT AIDE-DE-CAMP 1ST LIEUT ADJT FIRST LIEUTENANT ADJUTANT 1ST LIEUT ASST SURG FIRST LIEUTENANT ASSISTANT SURGEON 1ST LIEUT BN ADJT FIRST LIEUTENANT BATTALION ADJUTANT 1ST LIEUT REGTL QTR FIRST LIEUTENANT REGIMENTAL QUARTERMASTER 1ST LT FIRST LIEUTENANT 1ST MUS FIRST MUSICIAN 1ST OFFICER FIRST OFFICER 1ST SERG FIRST SERGEANT 1ST SGT FIRST SERGEANT 2 CL PVT SECOND CLASS PRIVATE 2 CL SPEC SECOND CLASS SPECIALIST 2D CORP SECOND CORPORAL 2D LIEUT SECOND LIEUTENANT 2D SERG SECOND SERGEANT 2LT SECOND LIEUTENANT 2ND LT SECOND LIEUTENANT 3 CL SPEC THIRD CLASS SPECIALIST 3D CORP THIRD CORPORAL 3D LIEUT THIRD LIEUTENANT 3D SERG THIRD SERGEANT 3RD OFFICER THIRD OFFICER 4 CL SPEC FOURTH CLASS SPECIALIST 4 CORP FOURTH CORPORAL 5 CL SPEC FIFTH CLASS SPECIALIST 6 CL SPEC SIXTH CLASS SPECIALIST ACTG HOSP STEW ACTING HOSPITAL STEWARD ADC AIDE-DE-CAMP ADJT ADJUTANT ARMORER ARMORER ART ARTIF ARTILLERY ARTIFICER ARTIF ARTIFICER ASST BAND LDR ASSISTANT BAND LEADER ASST ENGR CAC ASSISTANT ENGINEER ASST QTR MR ASSISTANT QUARTERMASTER ASST STEWARD ASSISTANT STEWARD ASST SURG ASSISTANT SURGEON AUX 1 CL SPEC AUXILARY 1ST CLASS SPECIALIST AVN CADET AVIATION CADET BAND CORP BAND CORPORAL BAND LDR BAND LEADER BAND SERG BAND SERGEANT BG BRIGADIER GENERAL BGLR BUGLER BGLR 1 CL BUGLER 1ST CLASS BLKSMITH BLACKSMITH BN COOK BATTALION COOK BN -

3RD BATTALION TAC NCO SERGEANT MAJOR ISAAC RAGUSA III United States Army

3RD BATTALION TAC NCO SERGEANT MAJOR ISAAC RAGUSA III United States Army The Citadel, Military College of South Carolina-- as of January, 2020 CSM (ret) Isaac Ragusa III is a native of Norristown, Pennsylvania. He enlisted in the United States Army in June of 1989 as an Infantryman. CSM Ragusa is currently the 3rd Battalion TAC NCO at The Citadel after 30 years of active duty service. While on active duty He has served as the Chief Military Science Instructor for The Citadel (The military College of South Carolina) Army ROTC Program, CSM (ret) Ragusa has served in every leadership position from Team Leader to Command Sergeant Major. His assignments include: Command Sergeant Major of The United States Army Marksmanship Unit at Ft Benning, GA; Command Sergeant Major of the 2nd Brigade 2-8 Infantry Regiment 4thID, Ft Carson, CO; Command Sergeant Major of the 4-6th IN BN and 2nd BN, 5th BCT 1AD, FT Bliss, TX; Command Sergeant Major and Operations Sergeant Major of the 4th Brigade Special Troops Battalion 508 PIR, 82D ABN at Ft Bragg, NC; ISG Bco and HHC 3-504th PIR, 82D at FT Bragg, NC; Scout Platoon Sergeant and A co Platoon Sergeant 3-504th PIR, 82D ABN at FT Bragg, NC; Instructor, Long Range Reconnaissance Course, 4th Ranger Training Battalion at FT Benning, GA; Team Leader, Long Range Surveillance Company XVIIIth Airborne Corps FT Bragg NC; Team Leader, Long Range Surveillance Detachment, 2nd AD at FT Hood, TX; Scout Observer, Long Range Surveillance Detachment, 5th ID Mechanized at FT Polk, LA; Machine Gunner 4- 6th Infantry Battalion, 5th Infantry Division FT Polk, LA. -

Declaration of Major Forms

William & Mary Office of the University Registrar Blow Memorial Hall Room 240 INSTRUCTIONS FOR PO Box 8795 Williamsburg, VA 23187-8795 DECLARATION/CHANGE OF MAJOR 757-221-2800 • Fax 757-221-2151 [email protected] To Declare a Major, you: • MUST wait until you have EARNED at least 39 credits (including transfer, AP, IB, not in-progress courses). Use the transcript to view the number of earned credits, not the DegreeWorks audit. • MUST declare when you EARNED 54 credits o Students who matriculated with AP, IB, or dual enrollment credits, however, may wait until they have earned 39 credits since high school graduation. o Transfer students entering with 54 or more credits may delay major declaration until the end of their first semester at the University. • MUST sign and your advisor MUST sign the form – the form will not be accepted without these signatures • There is a five business day processing time for declaration of major forms. Declared Major(s) may be changed at any time, but prior to the last day of add/drop in their final semester by submitting a new Declaration/Change of Major form to the Office of the University Registrar. SINGLE VS. DOUBLE MAJORS College of Arts & Sciences and School of Business You must declare a Major – you may also declare two majors; or one major and a minor. School of Education Elementary Education – you may also declare two majors or one major and a minor. Secondary Education – this is a licensure program, not a major. You must declare an Arts & Sciences Major in the subject area you wish to teach (English, Government, History, Math, a Science, Hispanic Studies, French, German or Latin). -

RAF Stories: the First 100 Years 1918 –2018

LARGE PRINT GUIDE Please return to the box for other visitors. RAF Stories: The First 100 Years 1918 –2018 Founding partner RAF Stories: The First 100 Years 1918–2018 The items in this case have been selected to offer a snapshot of life in the Royal Air Force over its first 100 years. Here we describe some of the fascinating stories behind these objects on display here. Case 1 RAF Roundel badge About 1990 For many, their first encounter with the RAF is at an air show or fair where a RAF recruiting van is present with its collection of recruiting brochures and, for younger visitors, free gifts like this RAF roundel badge. X004-5252 RAF Standard Pensioner Recruiter Badge Around 1935 For those who choose the RAF as a career, their journey will start at a recruiting office. Here the experienced staff will conduct tests and interviews and discuss options with the prospective candidate. 1987/1214/U 5 Dining Knife and Spoon 1938 On joining the RAF you would be issued with a number of essential items. This would have included set of eating irons consisting of a knife, fork and spoon. These examples have been stamped with the identification number of the person they were issued to. 71/Z/258 and 71/Z/259 Dining Fork 1940s The personal issue knife, fork and spoon set would not always be necessary. This fork would have been used in the Sergeant’s Mess at RAF Henlow. It is the standard RAF Nickel pattern but has been stamped with the RAF badge and name of the station presumably in an attempt to prevent individuals claiming it as their personal item. -

Change of Major Change of Major Concentration

CHANGE OF MAJOR CHANGE OF MAJOR CONCENTRATION Student Name Student USC ID Phone # □ change/declare major □ declare/change concentration current major current concentration add additional degree/major add additional concentration □ (Requires signatures from both Dept. Chairs) □ 1st major: Dept. Chair: current concentration 2nd major: Dept. Chair: remove additional major □ remove concentration/interest □ major not being removed: _ BACHELOR OF ARTS BACHELOR OF SCIENCE Biology (Concentration/Interest Optional) □ Communication Studies □ Coastal Ecology & Conservation □ □ Early Childhood Education (2.75 GPA required) □ Pre- Dental □ Marine Biology □ Pre-Pharmacy (2.75 GPA required) Elementary Education □ Pre-Veterinary □ Pre-Engineering English (Concentration Optional) □ Biomedical Sciences □ □ Pre-Medical □ Creative Writing □ Secondary Teacher Education Biology □ Professional Writing □ □ Business Administration (Concentration Required) English with Secondary English Language Arts □ Accounting □ Licensure □ Management Marketing History □ □ Computational Science □ Interest: Pre-Law □ □ Interest: Pre-Engineering Interdisciplinary Studies Information Science and Technology □ . Dept. Approval: □ □ IDST Online □ Hospitality Management □ Palmetto College □ Psychology . Program Director Approval: □ Palmetto College . Program Director Approval: _ □ Human Services □ Palmetto College . Palmetto College Advisor Approval: Sociology . Dept. Approval: □ Palmetto College □ Mathematics (Track Required) . Program Director Approval: _ □ □ Mathematical Sciences Studio Art (Concentration Optional) □ Secondary Teacher Education □ . Dept. Chair Approval: □ Media Art Public Health □ Interest: Pre-Nursing UNDECIDED □ □ Palmetto College . Undecided (Students with less than 60 earned credit hours) Program Director Approval: _ □ Are you an Honors student? (circle one) YES NO Student Signature: _ Date: Palmetto College Programs may increase/decrease fees Form Revised August 2020 . -

Military Pay Scales and Roles

Approximate What did their role involve? Rank/Rate (Service) Example Leavers’ Roles Pay Band All sugges5ons are trade and role dependent. MOD – Military Pay Scales as at 1 Apr 14 Other Ranks & Non-Commissioned and Warrant Officers Appren5ceship Recruit in Training £14,429.01 Contracts are set from 4 to 24 years. Training The Armed Forces: An Informa2on Sheet Senior AircraUman (RAF) Junior Technician Private / other e.g. Trooper (Army) Some technically skilled roles, others unskilled. HM Forces, the Services, the Military. Whichever 5tle Administrator Junior AircraUman/Tech £17,866.78 - you use, the Forces comprise three main Services : £29,521.18 • Royal Navy (RN or Navy) Able Rate (Navy) Driver Junior Supervisors, responsible for other’s work / behaviour in a small • Brish Army (Army) Lance Corporal Skilled technician team of 4-6 or component task. • Supervisors and team leaders of teams of around 8-10: required to take Royal Air Force (RAF) Leading Rate (Navy) £26,935.44 - Supervisor responsibility for organising and running training / task coordinaon. (The Royal Marines are part of the Naval service but align to the Corporal £33,849.23 Senior mechanic/technician rank structure of the Army.) May be responsible for running an equipment account / store. First rung of significant responsibility and administrave management: • In addi5on, each Service has a Reserve Force. Sergeant (Army / RAF) £30,615.80 - Junior Manager experienced and technically authoritave in their field. Support and Pey Officer (Navy) £37,671.30 Team Coordinator Talented Workforce advise the Officer in charge of a team of c.35 – keeps check both ways.