How Duncan Kennedy Caught the Hierarchy Zeitgeist but Missed the Point

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Smash Hits Volume 34

\ ^^9^^ 30p FORTNlGHTiy March 20-Aprii 2 1980 Words t0^ TOPr includi Ator-* Hap House €oir Underground to GAR! SKias in coioui GfiRR/£V£f/ mjlt< H/Kim TEEIM THAT TU/W imv UGCfMONSTERS/ J /f yO(/ WOULD LIKE A FREE COLOUR POSTER COPY OF THIS ADVERTISEMENT, FILL IN THE COUPON AND RETURN IT TO: HULK POSTER, PO BOXt, SUDBURY, SUFFOLK C010 6SL. I AGE (PLEASE TICK THE APPROPRIATE SOX) UNDER 13[JI3-f7\JlS AND OVER U OFFER CLOSES ON APRIL 30TH 1980 ALLOW 28 DAYS FOR DELIVERY (swcKCAmisMASi) I I I iNAME ADDRESS.. SHt ' -*^' L.-**^ ¥• Mar 20-April 2 1980 Vol 2 No. 6 ECHO BEACH Martha Muffins 4 First of all, a big hi to all new &The readers of Smash Hits, and ANOTHER NAIL IN MY HEART welcome to the magazine that Squeeze 4 brings your vinyl alive! A warm welcome back too to all our much GOING UNDERGROUND loved regular readers. In addition The Jam 5 to all your usual news, features and chart songwords, we've got ATOMIC some extras for you — your free Blondie 6 record, a mini-P/ as crossword prize — as well as an extra song HELLO I AM YOUR HEART and revamping our Bette Bright 13 reviews/opinion section. We've also got a brand new regular ROSIE feature starting this issue — Joan Armatrading 13 regular coverage of the independent label scene (on page Managing Editor KOOL IN THE KAFTAN Nick Logan 26) plus the results of the Smash B. A. Robertson 16 Hits Readers Poll which are on Editor pages 1 4 and 1 5. -

Reggatta De Blanc (White Reggae)

“Reggatta de Blanc (White Reggae) & the Commercial Rock Industry: Intersections of Race, Culture, and Appropriation in Bob Marley and The Police (1977-1983)” Colin Carey Music University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire Introduction Ethical Concerns Origins of Reggae This project was designed to approach a discussion about cultural and The appropriation of culturally sensitive music and expression is a musical appropriation in popular music. The connection between reggae and common, but often overlooked issue in popular music. It is important to mainstream rock was perhaps no more evident or lucrative than within the understand that Western cultures inherently possess a privilege that can musical career trajectory of the wildly popular new wave group, the Police be used to take advantage of other societies—especially those (1977–1983), comprised of lead singer/songwriter Sting (Gordon Sumner), comprising the so-called “third world.” The Police owe their substantial guitarist Andy Summers, drummer Stewart Copeland, and a promotional success to this imbalance, directly adapting the distinctive music cadre of behind-the-scenes agents and businessmen. Their particular practices of a foreign culture for their own musical purposes and industrial rock model enjoyed startlingly quick, widespread renown and recordings to create a sound that was unlike most popular rock groups success—within only a couple of years of their formation, the Police had of their time. This appropriation is further troubling in that it stripped the become the leading rock group of their time and would go on to influence the Jamaican source material of its definitive social and political direction of the music marketplace itself, including countless other acts such significance, gaining success instead through an appeal entirely as the then up-and-coming Irish group, U2. -

Artist Review: Revisiting Sting-An Under-Recognized Existentialist Song Writer1

International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Growth Evaluation www.allmultidisciplinaryjournal.com International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Growth Evaluation ISSN: 2582-7138 Received: 01-05-2021; Accepted: 18-05-2021 www.allmultidisciplinaryjournal.com Volume 2; Issue 3; May-June 2021; Page No. 550-561 Artist review: Revisiting sting-an under-recognized Existentialist song writer1 Li Jia International College, Krirk University, Thanon Ram Intra, Khwaeng Anusawari, Khet Bang Khen, Krung Thep, Maha Nakhon10220, Thailand Corresponding Author: Li Jia Abstract Artistic expressions such as songs and poetry are examples of a solo artist but also helped him in communicating his free activities and are privileged modes of revealing what the thoughts and ideals to the world. His music, words and life world is about. Art’s power, in the case of existentialism, is are inextricably linked and this can be seen in many of Sting to a large extent devoted to expressing the absurdity of the ’s confessional songs that have connections to events in his human condition since for the existentialists, the world in no personal life. Existential characteristics have affected Sting longer open to the human desire of meaning and order. Sting both as a person and a musician. This paper calls for more is included in this pool of gifted artist and his talent in making researches on his music legacy that the world owned him for songs has not only paved the way for his successful career as a long time. Keywords: Sting, Existentialist, Song Writer Introduction Artistic expressions such as songs and poetry are examples of free activities and are privileged modes of revealing what the world is about. -

Download the Archives Here

23.12.12 Merry Christmas Here comes the time for a family gathering. Hope your christmas tree will have ton of intersting presents for you. 22.12.12 Sting to perform in Jodhpur in march Sting is sheduled to perform in march (8, 9 or 10) for Jodhpur One World Retreat. It will be a private show for head injury victims. Only 250 couples will attend the party, with 30,000$ to 60,000$ donations. More information on jodhpuroneworld.org. 22.12.12 The last ship I made some updates to the "what we know about the play" on the forum. Please, check them to know all the informations about "The Last Ship", that could be released in 2013-2014. 16.12.12 Back to bass tour : the end The Back to bass tour has ended yesterday (well, that's what some fans hope) in Jakarta. You'll find all the tour history on the forum, and all informations about the "25 years" best of, that pointed the start of this world tour on this special page. What will follow ? We know that Sting's musical "The last ship" could be released in 2013/2014. We also know that he will perform in France and Marocco this summer. 10.12.12 Back to Bass last dates reports Follow the recent reports from the past shows from Back to Bass tour in Eastern Europe and Asia. Sting and his band met warm audiences (yesterday one in Manilla seems to have been the best from the tour according to Peter and Dominic's tweets and according to various Youtube crazy videos) You'll find pictures and videos on the forum. -

Volume XCVII, Number 6, November 13, 1981

HE LAWRENTIAN VOL. XCVll·NO. 6 - LAWRENCE UNIVERSITY. · APPLETON. WISCONSIN 54911 FRIDAY . NOVEMBER 13, 1981 Bond brings-Cloak Un'.~ersity Convo.cation contehlporarycomedy A!~.~. to 1:~!.~!}~!~~!r~~!. byDianne~deen coast, and the staggered plat; Edwin R. Bayley, Dean of the nal, Bayle! _corresponded with he receii:~e\:e .ui:iumnl , Edward} Bon~ hist .a _modernt forms llave been quilted to GtrathduaUte .Scho?l .of Journalism othbeli~ let?dmgb nehw.spaph~rs a11d Distinguished Service Award · British p aywr1g , given o resemble sand. Explained a e mvers1ty of California, pu ca 10ns ot m t 1s coun· from Lawrence U . 't b _ writing grim pieces on chang- Frielund, "This is kind of an Berkely, and Lawrence -.. aluin- try al}d abroad. From 1952 to ed on hi's serv·c tmvJersi Yali as 1 O ingthev10ent.re· I ali t1He~o· f con· ~vocative"ill but simple abstrac- nNus, w .speaUt?1s k · ~~esday, , 1953 , hdewtasf th~- w·1sco nsmcord·· Bayley was appointede ourn to sm.his temporary _sqc1ety. is pays1 . t1on. We didn't want to make a ov. .17 ' m a mvers1t)'. Con· respon en or -.. m~e, 1nc., an current position at the Univer· have aroused a great deal of real sea or a real beach, we yocat1on -at 11:10 a.m. m the was a regular contnbutor to the sity of California M h 1 controversy in England, and wanted · to abstract ChapeL New Republic and The 1969. on arc ' are seldom done in the United every'thing... the quilting is an 1':1r, Ba.yley, who was·born in Economist· of London. -

Sting: My Songs. Taos, New Mexico Concert Confirmed

STING: MY SONGS TAOS, NEW MEXICO CONCERT CONFIRMED Monday, September 2, 2019 – KIT CARSON PARK Photo Credit: Martin Kierszenbaum TAOS, NM - April 29, 2019 The Town of Taos, AMP Concerts and Cherrytree Management have confirmed that Sting will perform in Taos, New Mexico on Monday, September 2 at Kit Carson Park. Sting: My Songs will be a rollicking, dynamic show focusing on the most beloved songs written by Sting and spanning the 16-time Grammy Award winner’s prolific career with The Police and as a solo artist. Fans can expect to hear “Englishman In New York,” “Fields Of Gold,” “Shape Of My Heart,” “Every Breath You Take,” “Roxanne,” “Message In A Bottle” and many more, with Sting accompanied by an electric, rock ensemble. Tickets for Sting’s concert at Kit Carson Park on Monday, September 2 will go on sale starting Friday, May 3 at 10 AM at https://www.taos.org/sting. Members of Sting’s Fan Club will have the opportunity to access tickets in advance by visiting www.sting.com. While in town for the holiday weekend, visitors can take advantage of a wide array of outdoor recreation options, dozens of art galleries and museums, exceptional food, wine, beer and cocktail selections and unique shopping options available in Taos. Visit taos.org for more information on lodging, activities and trip ideas. ABOUT STING: Composer, singer-songwriter, actor, author, and activist Sting was born in Newcastle, England before moving to London in 1977 to form The Police with Stewart Copeland and Andy Summers. The band released five studio albums, earned six Grammy Awards and two Brits, and was inducted into The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2003. -

ANDY SUMMERS Pro-Chancellor, Andy Summers Has Achieved An

ANDY SUMMERS Pro-Chancellor, Andy Summers has achieved an international reputation as a musician, songwriter and producer, in the genres of rock, pop and jazz. A rock and jazz guitarist of wide experience and versatility, he co-founded The Police and enjoyed huge worldwide success with the band in the 1980s, and again in its recent reunion tour. He is also a published author and photographer. Andy Summers was born in Lancashire but grew up in the Bournemouth area. He was a self-taught guitarist (though later he studied classical guitar at California State University, Northridge) and he played in a variety of bands and styles in local clubs and hotels in the later 1950s. This early experience gave him a versatility and resourcefulness which have marked his whole career and which enabled him, even in his earlier years, to play and record with a very diverse range of well-known bands and solo artists including Zoot Money’s Big Roll Band, the Animals and the Soft Machine. His innovative guitar style has made dynamic use of electronic effects and synthesiser technology. In the 1980s and later his music has increasingly reflected his love of modern jazz. However, Andy Summers’ period of greatest popular success began in 1977 when he joined with Gordon Sumner (better known as Sting) and Stewart Copeland to found The Police. With their distinctive and innovative blend of rock, jazz and reggae styles, The Police became one of the most successful bands of all time, with world-wide chart-topping hits such as Every Breath You Take, Message in a Bottle and Walking on the Moon, not to mention 80 million album sales. -

Razorlight ‘America’

Rockschool Grade Pieces Razorlight ‘America’ Razorlight SONG TITLE: AMERICA ALBUM: RAZORLIGHT RELEASED: OCTOBER 2006 GENRE: INDIE ROCK PERSONNEL: JOHNNY BORRELL (GTR+VOX) BJORN ÅGREN (GTR) CARL DALEMO (BASS) ANDY BURROWS (DRUMS) LABEL: VERTIGO/MERCURY UK CHART PEAK: 1 US CHART PEAK: N/A BACKGROUND INFO ‘America’ is the chart topping single from the second Razorlight album. This record, hot on the heels of its predecessor, Up All Night, (see ‘V.I.C.E.’ in Hot Rock – Grade 2) went straight into the album charts at number 1. The first single, ‘In The Morning’ reached number 7 but ‘America’ went all the way to the top. NOTES Winchester born Andy Burrows replaced original THE BIGGER PICTURE Razorlight drummer, Christian Smith-Pancorvo, for this record and all subsequent live work. He joined Razorlight is a half English, half Swedish indie the band in late 2004 after a set of open auditions. rock band who grew out of the same London music Andy is not only a fine drummer but also plays guitar scene as the Libertines. Fronted by Johnny Borrell, and has shaped the songwriting within the band, the band achieved almost immediate success with sharing writing credits for the singles ‘America’ and its first recordings before releasing Up All Night, on ‘Before I Fall to Pieces’ with frontman Johnny Borrell. the Vertigo label, including the hit single V.I.C.E. The success of Up All Night was consolidated with the follow up album Razorlight which topped the RECOMMENDED LISTENING charts, going 4 times platinum (1.2 million sales plus) in the process. -

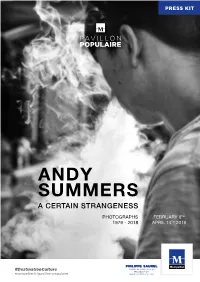

Andy Summers

PRESS KIT “Andy Summers. A certain strangeness, photographs 1979-2018” Pavillon Populaire - From February 6th to April 14th 2019 ANDY SUMMERS A CERTAIN STRANGENESS PHOTOGRAPHS FEBRUARY 6TH 1979 - 2018 APRIL 14TH 2019 #DestinationCulture montpellier.fr/pavillon-populaire “Andy Summers. A certain strangeness, photographs 1979-2018” Pavillon Populaire - From February 6th to April 14th 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS “Andy Summers. A certain strangeness, photographs 1979-2018” at the Pavillon Populaire in Montpellier from February 6th to April 14th 2019 . 4 Text of intent – Gilles Mora, artistic director of the Pavillon Populaire . 7 Text of intent – Andy Summers . 9 Artist’s biography . 10 2019 Pavillon Populaire programme . 11 Pavillon Populaire: photography made accessible for all. 12 Montpellier, a cultural destination . 13 Montpellier, a candidate for the European Capital of Culture . 17 Press images . 18 2 “Andy Summers. A certain strangeness, photographs 1979-2018” Pavillon Populaire - From February 6th to April 14th 2019 A WORD FROM PHILIPPE SAUREL The Pavillon Populaire 2018 season – dedicated to the link between history and photography – has been truly outstanding with more than 130 000 visitors for three exhibitions. In 2019, the Pavillon Populaire puts on a new event with the world of Andy Summers, photographer and guitarist of the mythic 80’s rock band The Police. Through his exhibition “A certain strangeness, photographs 1977-2018”, the artist presents us a dense masterpiece, quite similar to a private diary in form of pictures. With more than 250 images, most of which are yet unseen, the exhibition includes the series “Let’s get weird!”, a lucid and corrosive outlook on the ascent of the famous 80’s band. -

Smash Hits Volume 31

frs^vi Februar SON ALBUMS T , -V- ! W — I'm hypnotised the I He got a bike by m A motorbike — I got the hots for a drive up t. He like the beat — I got the beat I He like the heat — I got the beat He like the beat — I got the motorbike beat I Chorus y My favourite treat on the motorbike seat Is me and Mr CC He gotta drive — When I arrive you can hear the wheels ^ squeal He is alive — I got the feel for some mean steel appeal f P He got the steel — The squeal appeal ^ He got the feel — The steel appeal P He got the steel — I got the motorbike beat ta Repeat chorus \ But shouldn't we slow down, we're heading for >town i:*:i*»i*"**^^'- On the motorbike ^ Right — give it a kick then I drive it away ^ He flash alright — Ride in the night and I sleep in the day He bike away — Take it away 1 He ride away — I gotta say r He gotta say — I got the motorbike beat J Repeat chorus I Overtake all the creeps I When we go down the street r Me and Mr CC I Words and music by Eugene Reynolds/Fay Fife ' Ltd J Reproduced by permission Dinsong U-' MOTORBIKE BEAT Feb 7-Feb 20 1980 Vol 2 No. 3 The Revillos 2 First of all, for all you puzzled Police fans who are wondering LIVING BY NUMBERS where Stewart Copeland and New Musik 4 Andy Summers got to in this THE PLASTIC issue — relax. -

Copyrighted Material

INDEX A&M Records, 49, 61, 65, 75, 83, 84, 90, Berlin, Peter, 102 119, 136, 138, 144–146, 150, 167, Biafra, Jello, 152–153 241, 257 Blondie, 48, 83, 108, 153, 181, 268 Bring On the Night and, 209, 211 Boberg, Jay, 107, 153, 169 Bob Garcia and, 81, 107–108, 113, Body Mist (deodorant), 189, 195, 260 118, 168 “Bombs Away” (the Police), 139 I.R.S. and, 105–112, 152, 169 Boomtown Rats, 89, 181, 217 Jerry Moss and, 81, 94, 105–112, 152 Boorman, John, 135 Marketing the Police and, 80–86 Booz Allen Hamilton, 123 Miles Copeland III’s dealings with, 49, Bowie, David, 27, 151, 259 57–58, 61, 75–76, 81, 84, 105–113 Brand New Day (Sting), 256–258 new wave and, 94, 159 Branson, Richard, 15, 193–195 roster, 108 Bride, The, 228 Ahearn, Michael, 224 Bright, Terry, 157 Air Studios, 170–179, 199, 232 Brimstone and Treacle, 248 Alberto y Lost Trios Paranoias, 89, 114 Bring On the Night, 209–216 Alternative Tentacles, 153 “Bring On the Night” (the Police), 271 Alternative TV, 55, 112 British Talent Managers, 14, 72, 194 Altham, Keith, 99–100, 221 BTM Records, 14, 40, 165 Amnesty International, 221–226, 255, 262 Burbidge, Derek and Kate, 94–95, 119– Animals, the, 8, 9, 47 120, 123, 151, 180, 203 Apted, Michael, 209–212, 214 Burchill, Julie, 147–148 Atwood, Colleen, 212 Burdon, Eric, 8, 9 Ayers, Kevin, 8, 9, 43, 44, 49, 52 Bush, George H. W., 251 Bush, George W., 111 Bailey, David, 254 Buzzcocks, 109–110, 111, 112, 113 Bamberger, David,COPYRIGHTED 244–248 MATERIAL Bangles, the, 169 Cale, John, 109, 112 Bators, Stiv, 164–165, 167, 169 as producer of the Police, -

Turnê Inédita Em Homenagem Ao the Police Reúne Andy Summers E Integrantes Do Barão Vermelho E Dos Paralamas Do Sucesso No Palco

TURNÊ INÉDITA EM HOMENAGEM AO THE POLICE REÚNE ANDY SUMMERS E INTEGRANTES DO BARÃO VERMELHO E DOS PARALAMAS DO SUCESSO NO PALCO Com o show Call The Police, o eterno guitarrista da banda inglesa se apresentará no Auditório Araújo Vianna em abril acompanhado do baixista Rodrigo Santos e do baterista João Barone Andy Summers (The Police), Rodrigo Santos (Barão Vermelho) e João Barone (Paralamas do Sucesso) se reuniram para reverenciar nos palcos uma das maiores bandas da história do rock, o The Police. O trio já tem passagem garantida por Porto Alegre neste ano com a turnê inédita Call The Police. Realizado pela Opus Promoções e pela Branco Produções, o show acontecerá no Auditório Araújo Vianna dia 8 de abril, às 21h. Os ingressos começam a ser vendidos nesta sexta-feira. Confira o serviço completo abaixo. O baixista, compositor e cantor Rodrigo Santos e o lendário guitarrista inglês Andy Summers, do The Police, se conheceram no Rio de Janeiro em 2014, por intermédio do empresário Luiz Paulo Assunção, responsável pelo agenciamento de ambos. A partir daí iniciaram uma amizade musical que já se transformou em parceria e várias apresentações que mesclavam hits do The Police, do Barão Vermelho e da trajetória solo de Rodrigo Santos. Agora, Andy Summers volta a dividir o palco com Rodrigo e um novo e ilustre integrante, que completa o trio à frente do projeto batizado de Call the Police. “Dessa vez, diferentemente das outras turnês, faremos apenas repertório do The Police e a principal novidade é a chegada do João Barone. Já tínhamos tocado juntos, mas conviver e fazer ensaios, levando um som divertido e emocionante, só agora aconteceu”, celebra Rodrigo que, mais uma vez, encara a responsabilidade de assumir os vocais das canções gravadas por Sting.