Basics of the Differential Geometry of Curves

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parametric Surfaces and 16.6 Their Areas Parametric Surfaces

Parametric Surfaces and 16.6 Their Areas Parametric Surfaces 2 Parametric Surfaces Similarly to describing a space curve by a vector function r(t) of a single parameter t, a surface can be expressed by a vector function r(u, v) of two parameters u and v. Suppose r(u, v) = x(u, v)i + y(u, v)j + z(u, v)k is a vector-valued function defined on a region D in the uv-plane. So x, y, and, z, the component functions of r, are functions of the two variables u and v with domain D. The set of all points (x, y, z) in R3 s.t. x = x(u, v), y = y(u, v), z = z(u, v) and (u, v) varies throughout D, is called a parametric surface S. Typical surfaces: Cylinders, spheres, quadric surfaces, etc. 3 Example 3 – Important From Book The vector equation of a plane through (x0, y0, z0) and containing vectors is rather 4 Example – Point on Surface? Does the point (2, 3, 3) lie on the given surface? How about (1, 2, 1)? 5 Example – Identify the Surface Identify the surface with the given vector equation. 6 Example – Identify the Surface Identify the surface with the given vector equation. 7 Example – Find a Parametric Equation The part of the hyperboloid –x2 – y2 + z = 1 that lies below the rectangle [–1, 1] X [–3, 3]. 8 Example – Find a Parametric Equation The part of the cylinder x2 + z2 = 1 that lies between the planes y = 1 and y = 3. 9 Example – Find a Parametric Equation Part of the plane z = 5 that lies inside the cylinder x2 + y2 = 16. -

INTRODUCTION to ALGEBRAIC GEOMETRY, CLASS 25 Contents 1

INTRODUCTION TO ALGEBRAIC GEOMETRY, CLASS 25 RAVI VAKIL Contents 1. The genus of a nonsingular projective curve 1 2. The Riemann-Roch Theorem with Applications but No Proof 2 2.1. A criterion for closed immersions 3 3. Recap of course 6 PS10 back today; PS11 due today. PS12 due Monday December 13. 1. The genus of a nonsingular projective curve The definition I’m going to give you isn’t the one people would typically start with. I prefer to introduce this one here, because it is more easily computable. Definition. The tentative genus of a nonsingular projective curve C is given by 1 − deg ΩC =2g 2. Fact (from Riemann-Roch, later). g is always a nonnegative integer, i.e. deg K = −2, 0, 2,.... Complex picture: Riemann-surface with g “holes”. Examples. Hence P1 has genus 0, smooth plane cubics have genus 1, etc. Exercise: Hyperelliptic curves. Suppose f(x0,x1) is a polynomial of homo- geneous degree n where n is even. Let C0 be the affine plane curve given by 2 y = f(1,x1), with the generically 2-to-1 cover C0 → U0.LetC1be the affine 2 plane curve given by z = f(x0, 1), with the generically 2-to-1 cover C1 → U1. Check that C0 and C1 are nonsingular. Show that you can glue together C0 and C1 (and the double covers) so as to give a double cover C → P1. (For computational convenience, you may assume that neither [0; 1] nor [1; 0] are zeros of f.) What goes wrong if n is odd? Show that the tentative genus of C is n/2 − 1.(Thisisa special case of the Riemann-Hurwitz formula.) This provides examples of curves of any genus. -

Algebraic Geometry Michael Stoll

Introductory Geometry Course No. 100 351 Fall 2005 Second Part: Algebraic Geometry Michael Stoll Contents 1. What Is Algebraic Geometry? 2 2. Affine Spaces and Algebraic Sets 3 3. Projective Spaces and Algebraic Sets 6 4. Projective Closure and Affine Patches 9 5. Morphisms and Rational Maps 11 6. Curves — Local Properties 14 7. B´ezout’sTheorem 18 2 1. What Is Algebraic Geometry? Linear Algebra can be seen (in parts at least) as the study of systems of linear equations. In geometric terms, this can be interpreted as the study of linear (or affine) subspaces of Cn (say). Algebraic Geometry generalizes this in a natural way be looking at systems of polynomial equations. Their geometric realizations (their solution sets in Cn, say) are called algebraic varieties. Many questions one can study in various parts of mathematics lead in a natural way to (systems of) polynomial equations, to which the methods of Algebraic Geometry can be applied. Algebraic Geometry provides a translation between algebra (solutions of equations) and geometry (points on algebraic varieties). The methods are mostly algebraic, but the geometry provides the intuition. Compared to Differential Geometry, in Algebraic Geometry we consider a rather restricted class of “manifolds” — those given by polynomial equations (we can allow “singularities”, however). For example, y = cos x defines a perfectly nice differentiable curve in the plane, but not an algebraic curve. In return, we can get stronger results, for example a criterion for the existence of solutions (in the complex numbers), or statements on the number of solutions (for example when intersecting two curves), or classification results. -

Trigonometry Cram Sheet

Trigonometry Cram Sheet August 3, 2016 Contents 6.2 Identities . 8 1 Definition 2 7 Relationships Between Sides and Angles 9 1.1 Extensions to Angles > 90◦ . 2 7.1 Law of Sines . 9 1.2 The Unit Circle . 2 7.2 Law of Cosines . 9 1.3 Degrees and Radians . 2 7.3 Law of Tangents . 9 1.4 Signs and Variations . 2 7.4 Law of Cotangents . 9 7.5 Mollweide’s Formula . 9 2 Properties and General Forms 3 7.6 Stewart’s Theorem . 9 2.1 Properties . 3 7.7 Angles in Terms of Sides . 9 2.1.1 sin x ................... 3 2.1.2 cos x ................... 3 8 Solving Triangles 10 2.1.3 tan x ................... 3 8.1 AAS/ASA Triangle . 10 2.1.4 csc x ................... 3 8.2 SAS Triangle . 10 2.1.5 sec x ................... 3 8.3 SSS Triangle . 10 2.1.6 cot x ................... 3 8.4 SSA Triangle . 11 2.2 General Forms of Trigonometric Functions . 3 8.5 Right Triangle . 11 3 Identities 4 9 Polar Coordinates 11 3.1 Basic Identities . 4 9.1 Properties . 11 3.2 Sum and Difference . 4 9.2 Coordinate Transformation . 11 3.3 Double Angle . 4 3.4 Half Angle . 4 10 Special Polar Graphs 11 3.5 Multiple Angle . 4 10.1 Limaçon of Pascal . 12 3.6 Power Reduction . 5 10.2 Rose . 13 3.7 Product to Sum . 5 10.3 Spiral of Archimedes . 13 3.8 Sum to Product . 5 10.4 Lemniscate of Bernoulli . 13 3.9 Linear Combinations . -

J.M. Sullivan, TU Berlin A: Curves Diff Geom I, SS 2019 This Course Is an Introduction to the Geometry of Smooth Curves and Surf

J.M. Sullivan, TU Berlin A: Curves Diff Geom I, SS 2019 This course is an introduction to the geometry of smooth if the velocity never vanishes). Then the speed is a (smooth) curves and surfaces in Euclidean space Rn (in particular for positive function of t. (The cusped curve β above is not regular n = 2; 3). The local shape of a curve or surface is described at t = 0; the other examples given are regular.) in terms of its curvatures. Many of the big theorems in the DE The lengthR [ : Länge] of a smooth curve α is defined as subject – such as the Gauss–Bonnet theorem, a highlight at the j j len(α) = I α˙(t) dt. (For a closed curve, of course, we should end of the semester – deal with integrals of curvature. Some integrate from 0 to T instead of over the whole real line.) For of these integrals are topological constants, unchanged under any subinterval [a; b] ⊂ I, we see that deformation of the original curve or surface. Z b Z b We will usually describe particular curves and surfaces jα˙(t)j dt ≥ α˙(t) dt = α(b) − α(a) : locally via parametrizations, rather than, say, as level sets. a a Whereas in algebraic geometry, the unit circle is typically be described as the level set x2 + y2 = 1, we might instead This simply means that the length of any curve is at least the parametrize it as (cos t; sin t). straight-line distance between its endpoints. Of course, by Euclidean space [DE: euklidischer Raum] The length of an arbitrary curve can be defined (following n we mean the vector space R 3 x = (x1;:::; xn), equipped Jordan) as its total variation: with with the standard inner product or scalar product [DE: P Xn Skalarproduktp ] ha; bi = a · b := aibi and its associated norm len(α):= TV(α):= sup α(ti) − α(ti−1) : jaj := ha; ai. -

The Osculating Circumference Problem

THE OSCULATING CIRCUMFERENCE PROBLEM School I.S.I.S.S. M. Casagrande Pieve di Soligo, Treviso Italy Students Silvia Micheletto (I) Azzurra Soa Pizzolotto (IV) Luca Barisan (II) Simona Sota (IV) Gaia Barella (IV) Paolo Barisan (V) Marco Casagrande (IV) Anna De Biasi (V) Chiara De Rosso (IV) Silvia Giovani (V) Maddalena Favaro (IV) Klara Metaliu (V) Teachers Fabio Breda Francesco Maria Cardano Davide Palma Francesco Zampieri Researcher Alberto Zanardo, University of Padova Italy Year 2019/2020 The osculating circumference problem ISISS M. Casagrande, Pieve di Soligo, Treviso Italy Abstract The aim of the article is to study the osculating circumference i.e. the circumference which best approximates the graph of a curve at one of its points. We will dene this circumference and we will describe several methods to nd it. Finally we will introduce the notions of round points and crossing points, points of the curve where the circumference has interesting properties. ??? Contents Introduction 3 1 The osculating circumference 5 1.1 Particular cases: the formulas cannot be applied . 9 1.2 Curvature . 14 2 Round points 15 3 Beyond round points 22 3.1 Crossing points . 23 4 Osculating circumference of a conic section 25 4.1 The rst method . 25 4.2 The second method . 26 References 31 2 The osculating circumference problem ISISS M. Casagrande, Pieve di Soligo, Treviso Italy Introduction Our research was born from an analytic geometry problem studied during the third year of high school. The problem. Let P : y = x2 be a parabola and A and B two points of the curve symmetrical about the axis of the parabola. -

Plotting Graphs of Parametric Equations

Parametric Curve Plotter This Java Applet plots the graph of various primary curves described by parametric equations, and the graphs of some of the auxiliary curves associ- ated with the primary curves, such as the evolute, involute, parallel, pedal, and reciprocal curves. It has been tested on Netscape 3.0, 4.04, and 4.05, Internet Explorer 4.04, and on the Hot Java browser. It has not yet been run through the official Java compilers from Sun, but this is imminent. It seems to work best on Netscape 4.04. There are problems with Netscape 4.05 and it should be avoided until fixed. The applet was developed on a 200 MHz Pentium MMX system at 1024×768 resolution. (Cost: $4000 in March, 1997. Replacement cost: $695 in June, 1998, if you can find one this slow on sale!) For various reasons, it runs extremely slowly on Macintoshes, and slowly on Sun Sparc stations. The curves should move as quickly as Roadrunner cartoons: for a benchmark, check out the circular trigonometric diagrams on my Java page. This applet was mainly done as an exercise in Java programming leading up to more serious interactive animations in three-dimensional graphics, so no attempt was made to be comprehensive. Those who wish to see much more comprehensive sets of curves should look at: http : ==www − groups:dcs:st − and:ac:uk= ∼ history=Java= http : ==www:best:com= ∼ xah=SpecialP laneCurve dir=specialP laneCurves:html http : ==www:astro:virginia:edu= ∼ eww6n=math=math0:html Disclaimer: Like all computer graphics systems used to illustrate mathematical con- cepts, it cannot be error-free. -

Multivariable and Vector Calculus

Multivariable and Vector Calculus Lecture Notes for MATH 0200 (Spring 2015) Frederick Tsz-Ho Fong Department of Mathematics Brown University Contents 1 Three-Dimensional Space ....................................5 1.1 Rectangular Coordinates in R3 5 1.2 Dot Product7 1.3 Cross Product9 1.4 Lines and Planes 11 1.5 Parametric Curves 13 2 Partial Differentiations ....................................... 19 2.1 Functions of Several Variables 19 2.2 Partial Derivatives 22 2.3 Chain Rule 26 2.4 Directional Derivatives 30 2.5 Tangent Planes 34 2.6 Local Extrema 36 2.7 Lagrange’s Multiplier 41 2.8 Optimizations 46 3 Multiple Integrations ........................................ 49 3.1 Double Integrals in Rectangular Coordinates 49 3.2 Fubini’s Theorem for General Regions 53 3.3 Double Integrals in Polar Coordinates 57 3.4 Triple Integrals in Rectangular Coordinates 62 3.5 Triple Integrals in Cylindrical Coordinates 67 3.6 Triple Integrals in Spherical Coordinates 70 4 Vector Calculus ............................................ 75 4.1 Vector Fields on R2 and R3 75 4.2 Line Integrals of Vector Fields 83 4.3 Conservative Vector Fields 88 4.4 Green’s Theorem 98 4.5 Parametric Surfaces 105 4.6 Stokes’ Theorem 120 4.7 Divergence Theorem 127 5 Topics in Physics and Engineering .......................... 133 5.1 Coulomb’s Law 133 5.2 Introduction to Maxwell’s Equations 137 5.3 Heat Diffusion 141 5.4 Dirac Delta Functions 144 1 — Three-Dimensional Space 1.1 Rectangular Coordinates in R3 Throughout the course, we will use an ordered triple (x, y, z) to represent a point in the three dimensional space. -

Math 1300 Section 4.8: Parametric Equations A

MATH 1300 SECTION 4.8: PARAMETRIC EQUATIONS A parametric equation is a collection of equations x = x(t) y = y(t) that gives the variables x and y as functions of a parameter t. Any real number t then corresponds to a point in the xy-plane given by the coordi- nates (x(t); y(t)). If we think about the parameter t as time, then we can interpret t = 0 as the point where we start, and as t increases, the parametric equation traces out a curve in the plane, which we will call a parametric curve. (x(t); y(t)) • The result is that we can \draw" curves just like an Etch-a-sketch! animated parametric circle from wolfram Date: 11/06. 1 4.8 2 Let's consider an example. Suppose we have the following parametric equation: x = cos(t) y = sin(t) We know from the pythagorean theorem that this parametric equation satisfies the relation x2 + y2 = 1 , so we see that as t varies over the real numbers we will trace out the unit circle! Lets look at the curve that is drawn for 0 ≤ t ≤ π. Just picking a few values we can observe that this parametric equation parametrizes the upper semi-circle in a counter clockwise direction. (0; 1) • t x(t) y(t) 0 1 0 p p π 2 2 •(1; 0) 4 2 2 π 2 0 1 π -1 0 Looking at the curve traced out over any interval of time longer that 2π will indeed trace out the entire circle. -

Geodetic Position Computations

GEODETIC POSITION COMPUTATIONS E. J. KRAKIWSKY D. B. THOMSON February 1974 TECHNICALLECTURE NOTES REPORT NO.NO. 21739 PREFACE In order to make our extensive series of lecture notes more readily available, we have scanned the old master copies and produced electronic versions in Portable Document Format. The quality of the images varies depending on the quality of the originals. The images have not been converted to searchable text. GEODETIC POSITION COMPUTATIONS E.J. Krakiwsky D.B. Thomson Department of Geodesy and Geomatics Engineering University of New Brunswick P.O. Box 4400 Fredericton. N .B. Canada E3B5A3 February 197 4 Latest Reprinting December 1995 PREFACE The purpose of these notes is to give the theory and use of some methods of computing the geodetic positions of points on a reference ellipsoid and on the terrain. Justification for the first three sections o{ these lecture notes, which are concerned with the classical problem of "cCDputation of geodetic positions on the surface of an ellipsoid" is not easy to come by. It can onl.y be stated that the attempt has been to produce a self contained package , cont8.i.ning the complete development of same representative methods that exist in the literature. The last section is an introduction to three dimensional computation methods , and is offered as an alternative to the classical approach. Several problems, and their respective solutions, are presented. The approach t~en herein is to perform complete derivations, thus stqing awrq f'rcm the practice of giving a list of for11111lae to use in the solution of' a problem. -

Design Data 21

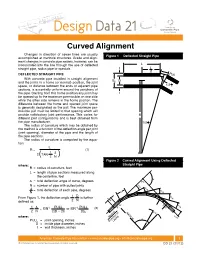

Design Data 21 Curved Alignment Changes in direction of sewer lines are usually Figure 1 Deflected Straight Pipe accomplished at manhole structures. Grade and align- Figure 1 Deflected Straight Pipe ment changes in concrete pipe sewers, however, can be incorporated into the line through the use of deflected L straight pipe, radius pipe or specials. t L 2 DEFLECTED STRAIGHT PIPE Pull With concrete pipe installed in straight alignment Bc D and the joints in a home (or normal) position, the joint ∆ space, or distance between the ends of adjacent pipe 1/2 N sections, is essentially uniform around the periphery of the pipe. Starting from this home position any joint may t be opened up to the maximum permissible on one side while the other side remains in the home position. The difference between the home and opened joint space is generally designated as the pull. The maximum per- missible pull must be limited to that opening which will provide satisfactory joint performance. This varies for R different joint configurations and is best obtained from the pipe manufacturer. ∆ 1/2 N The radius of curvature which may be obtained by this method is a function of the deflection angle per joint (joint opening), diameter of the pipe and the length of the pipe sections. The radius of curvature is computed by the equa- tion: L R = (1) 1 ∆ 2 TAN ( 2 N ) Figure 2 Curved Alignment Using Deflected Figure 2 Curved Alignment Using Deflected where: Straight Pipe R = radius of curvature, feet Straight Pipe L = length of pipe sections measured along the centerline, feet ∆ ∆ = total deflection angle of curve, degrees P.I. -

Combining Points and Tangents Into Parabolic Polygons: an Affine

Combining points and tangents into parabolic polygons: an affine invariant model for plane curves MARCOS CRAIZER1,THOMAS LEWINER1 AND JEAN-MARIE MORVAN2 1 Department of Mathematics — Pontif´ıcia Universidade Catolica´ — Rio de Janeiro — Brazil 2 Universite´ Claude Bernard — Lyon — France {craizer, tomlew}@mat.puc--rio.br. [email protected]. Abstract. Image and geometry processing applications estimate the local geometry of objects using information localized at points. They usually consider information about the tangents as a side product of the points coordinates. This work proposes parabolic polygons as a model for discrete curves, which intrinsically combines points and tangents. This model is naturally affine invariant, which makes it particularly adapted to computer vision applications. As a direct application of this affine invariance, this paper introduces an affine curvature estimator that has a great potential to improve computer vision tasks such as matching and registering. As a proof–of–concept, this work also proposes an affine invariant curve reconstruction from point and tangent data. Keywords: Affine Differential Geometry. Affine Curvature. Affine Length. Curve Reconstruction. Figure 1: Parabolic polygon (right) obtained from a Lissajous curve with 10 samples vs. straight line polygon ignoring tangents (left). 1 Introduction measures. These normals can also be robustly estimated only from the point coordinates [11, 9], or from direct image pro- Computers represent geometric objects through discrete cessing [5, 16]. structures. These structures usually rely on point-wise in- formation combined with adjacency relations. In particular, However, the normal or tangent information is usually most geometry processing applications require the normal of considered separately from the point coordinate, and the def- the object at each point: either for rendering [15], deforma- inition of geometrical objects such as contour curves or dis- tion [4], or numerical stability of reconstruction [1].